Charles Hopkinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nahant Reconnaissance Report

NAHANT RECONNAISSANCE REPORT ESSEX COUNTY LANDSCAPE INVENTORY MASSACHUSETTS HERITAGE LANDSCAPE INVENTORY PROGRAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Essex National Heritage Commission PROJECT TEAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Jessica Rowcroft, Preservation Planner Division of Planning and Engineering Essex National Heritage Commission Bill Steelman, Director of Heritage Preservation Project Consultants Shary Page Berg Gretchen G. Schuler Virginia Adams, PAL Local Project Coordinator Linda Pivacek Local Heritage Landscape Participants Debbie Aliff John Benson Mark Cullinan Dan deStefano Priscilla Fitch Jonathan Gilman Tom LeBlanc Michael Manning Bill Pivacek Linda Pivacek Emily Potts Octavia Randolph Edith Richardson Calantha Sears Lynne Spencer Julie Stoller Robert Wilson Bernard Yadoff May 2005 INTRODUCTION Essex County is known for its unusually rich and varied landscapes, which are represented in each of its 34 municipalities. Heritage landscapes are those places that are created by human interaction with the natural environment. They are dynamic and evolving; they reflect the history of the community and provide a sense of place; they show the natural ecology that influenced the land use in a community; and heritage landscapes often have scenic qualities. This wealth of landscapes is central to each community’s character; yet heritage landscapes are vulnerable and ever changing. For this reason it is important to take the first steps toward their preservation by identifying those landscapes that are particularly valued by the community – a favorite local farm, a distinctive neighborhood or mill village, a unique natural feature, an inland river corridor or the rocky coast. To this end, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and the Essex National Heritage Commission (ENHC) have collaborated to bring the Heritage Landscape Inventory program (HLI) to communities in Essex County. -

A NEWSLETTER from the CAPE ANN VERNAL POND TEAM Winter/Spring 2015 Website: Email: [email protected]

A NEWSLETTER from the CAPE ANN VERNAL POND TEAM Winter/Spring 2015 Website: www.capeannvernalpond.org Email: [email protected] THE CAVPT IS A HOPELESSLY NON-PROFIT VOLUNTEER ORGANIZATION DEDICATED TO VERNAL POND CONSERVATION AND EDUCATION SINCE 1990. This year we celebrate our 25th anniversary. With the help, inspiration, and commitment of a lot of people we’ve come a long way! Before we get into our own history we have to give a nod to Roger Ward Babson (1875-1967) who had the foresight to • The Pole’s Hill ladies - led by Nan Andrew, Virginia Dench, preserve the watershed land in the center of Cape Ann known as and Dina Enos were inspirational as a small group of people who Dogtown. His love of Dogtown began as a young boy when he organized to preserve an important piece of land; the Vernal Pond would accompany his grandfather on Sunday afternoon walks to Team was inspired by their success. Hey, you really can make a difference! bring rock salt to the cows that grazed there. After his grandfa- ther passed away he continued the • CAVPT received its first grant ($200 from tradition with his father, Nathaniel. New England Herpetological Society) for When Nathaniel died in 1927 Roger film and developing to aid in certifying pools. began purchasing tracts of land to preserve Dogtown. In all he purchased • By 1995 we certified our first pools, the 1,150 acres, which he donated to cluster of nine ponds on Nugent Stretch at the City of Gloucester in 1932, to be old Rockport Road (where the vernal pond used as a park and watershed. -

The Massachusetts Bay Hydrodynamic Model: 2005 Simulation

The Massachusetts Bay Hydrodynamic Model: 2005 Simulation Massachusetts Water Resources Authority Environmental Quality Department Report ENQUAD 2008-12 Jiang MS, Zhou M. 2008. The Massachusetts Bay Hydrodynamic Model: 2005 Simulation. Boston: Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. Report 2008-12. 58 pp. Massachusetts Water Resources Authority Boston, Massachusetts The Massachusetts Bay Hydrodynamic Model: 2005 Simulation Prepared by: Mingshun Jiang & Meng Zhou Department of Environmental, Earth and Ocean Sciences University of Massachusetts Boston 100 Morrissey Blvd Boston, MA 02125 July 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Boston Harbor, Massachusetts Bay and Cape Cod Bay system (MBS) is a semi- enclosed coastal system connected to the Gulf of Maine (GOM) through boundary exchange. Both natural processes including climate change, seasonal variations and episodic events, and human activities including nutrient inputs and fisheries affect the physical and biogeochemical environment in the MBS. Monitoring and understanding of physical–biogeochemical processes in the MBS is important to resource management and environmental mitigation. Since 1992, the Massachusetts Water Resource Authority (MWRA) has been monitoring the MBS in one of the nation’s most comprehensive monitoring programs. Under a cooperative agreement between the MWRA and University of Massachusetts Boston (UMB), the UMB modeling team has conducted numerical simulations of the physical–biogeochemical conditions and processes in the MBS during 2000-2004. Under a new agreement between MWRA, Battelle and UMB, the UMB continues to conduct a numerical simulation for 2005, a year in which the MBS experienced an unprecedented red–tide event that cost tens of millions dollars to Massachusetts shellfish industry. This report presents the model validation and simulated physical environment in 2005. -

East Point History Text from Uniguide Audiotour

East Point History Text from UniGuide audiotour Last updated October 14, 2017 This is an official self-guided and streamable audio tour of East Point, Nahant. It highlights the natural, cultural, and military history of the site, as well as current research and education happening at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center. Content was developed by the Northeastern University Marine Science Center with input from the Nahant Historical Society and Nahant SWIM Inc., as well as Nahant residents Gerry Butler and Linda Pivacek. 1. Stop 1 Welcome to East Point and the Northeastern University Marine Science Center. This site, which also includes property owned and managed by the Town of Nahant, boasts rich cultural and natural histories. We hope you will enjoy the tour Settlement in the Nahant area began about 10,000 years ago during the Paleo-Indian era. In 1614, the English explorer Captain John Smith reported: the “Mattahunts, two pleasant Iles of grouse, gardens and corn fields a league in the Sea from the Mayne.” Poquanum, a Sachem of Nahant, “sold” the island several times, beginning in 1630 with Thomas Dexter, now immortalized on the town seal. The geography of East Point includes one of the best examples of rocky intertidal habitat in the southern Gulf of Maine, and very likely the most-studied as well. This site is comprised of rocky headlands and lower areas that become exposed between high tide and low tide. This zone is easily identified by the many pools of seawater left behind as the water level drops during low tide. The unique conditions in these tidepools, and the prolific diversity of living organisms found there, are part of what interests scientists, as well as how this ecosystem will respond to warming and rising seas resulting from climate change. -

March 28 2018 Compensation Committee Meeting Packet

NANTUCKET REGIONAL TRANSIT AUTHORITY 20 R South Water Street Nantucket, MA 02554 Phone: 508-325-9571 TTY: 508-325-7516 [email protected] www.nrtawave.com AGENDA FOR THE MEETING OF THE COMPENSATION COMMITTEE of the NRTA ADVISORY BOARD MARCH 28, 2018 10:00 a.m. TOWN HALL CONFERENCE ROOM 16 BROAD STREET NANTUCKET, MASSACHUSETTS OPEN SESSION I. Approval of Minutes of the March 22, 2017 Meeting. II. Evaluate Compensation for Authority Executive per 801 CMR 53.00. NANTUCKET REGIONAL TRANSIT AUTHORITY 20 R South Water Street Nantucket, MA 02554 Phone: 508-325-9571 TTY: 508-325-7516 [email protected] www.nrtawave.com Compensation Committee DRAFT Minutes of the Compensation Committee Meeting of March 22, 2017. The meeting took place in the Community Room of the Nantucket Police Station, 4 Fairgrounds Road, Nantucket, MA 02554. Members of the Board present were: Jim Kelly, Robert DeCosta, Rick Atherton, Matthew Fee, and Dawn Hill Holdgate. Absent: Karenlynn Williams. Chairman Kelly opened the meeting at 6:02 p.m. Approval of Minutes of the March 23, 2016 Meeting. The minutes of the March 23, 2016 meeting were approved by unanimous consent of the Board. Evaluate Compensation for Authority Executive per 801 CMR 53.00. Paula Leary, NRTA Administrator informed the Board that the prior fiscal year salary, benefits and comparison lists of the regional transit authorities have been provided to the Board. As required under 081 CMR 53 the Board is to look at RTA executive positions in comparison to the NRTA Administrator. Paula Leary, NRTA Administrator stated a 5% COLA is being requested. -

CPB1 C10 WEB.Pdf

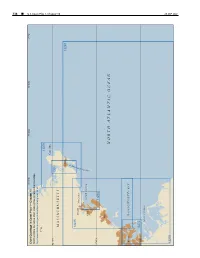

338 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 Chapter 1, Pilot Coast U.S. 70°45'W 70°30'W 70°15'W 71°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 1—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 71°W 13279 Cape Ann 42°40'N 13281 MASSACHUSETTS Gloucester 13267 R O B R A 13275 H Beverly R Manchester E T S E C SALEM SOUND U O Salem L G 42°30'N 13276 Lynn NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Boston MASSACHUSETTS BAY 42°20'N 13272 BOSTON HARBOR 26 SEP2021 13270 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 ¢ 339 Cape Ann to Boston Harbor, Massachusetts (1) This chapter describes the Massachusetts coast along and 234 miles from New York. The entrance is marked on the northwestern shore of Massachusetts Bay from Cape its eastern side by Eastern Point Light. There is an outer Ann southwestward to but not including Boston Harbor. and inner harbor, the former having depths generally of The harbors of Gloucester, Manchester, Beverly, Salem, 18 to 52 feet and the latter, depths of 15 to 24 feet. Marblehead, Swampscott and Lynn are discussed as are (11) Gloucester Inner Harbor limits begin at a line most of the islands and dangers off the entrances to these between Black Rock Danger Daybeacon and Fort Point. harbors. (12) Gloucester is a city of great historical interest, the (2) first permanent settlement having been established in COLREGS Demarcation Lines 1623. The city limits cover the greater part of Cape Ann (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are and part of the mainland as far west as Magnolia Harbor. -

Cape Ann Museum 2 0 1 2 Annual Report

CAPE ANN MUSEUM 2 0 1 2 A N N U A L REPORT OUR MISSION To foster an appreciation of the quality and Dear Friends, diversity of life on Cape Ann, past and present; It is with great pleasure that we present our 2012 Annual Report. To further the knowledge and enjoyment For 140 years, the Cape Ann Museum has embodied and promot- of Cape Ann history and art; ed the rich historic and artistic legacy of our region. It is a legacy To collect and preserve significant of which we are very proud. This annual recounting is both a cel- information and artifacts; and, ebration of the milestones we reached during the past year, and, To encourage community involvement we hope, a catalyst for future accomplishments. in our programs and holdings. A few years ago, as part of our Strategic Plan (2010 –2016), we In all our activities, the Museum emphasizes set on the path to become one of the best small museums in the the highest standards of quality. country. We are pleased to report that we are on our way. 2012 was an amazing year: • Membership, attendance and support reached all time highs due to your generosity and to the commitment of our board, staff and volunteers. • We honored our maritime heritage with the exhibition Ships at Sea. • We drew connections between Cape Ann’s creative past and the work of contemporary artists with the exhibitions Marsden Hartley: Soliloquy in Dogtown and Sarah Hollis Perry and Rachel Perry Welty’s water, water. • We initiated the Fitz Henry Lane Online project, a “digital” catalogue raisonné, which promises to put the Cape Ann Museum at the forefront of Lane scholarship. -

2016 GOMSWG Census Data Table

2016 Gulf of Maine Seabird Working Group Census Results Census Window: June 12-22 (peak of tern incubation) (Results from region-wide count period are reported here - refer to island synopsis or contact island staff for season totals) *not located in the Gulf of Maine or included in GOM totals numbers need to be verified ISLAND NAME DATE METHOD COTE ARTE ROST LETE LAGU FLEDGE/NEST N SD METHOD EGGS/NEST N SD OBSERVER NOVA SCOTIA 6/12 N 619 Julie McKnight North Brother 6/12 N 35 Julie McKnight South Brother Grassy Island 6/17 - 6/20 N 893 1.23 39 0.20 1, 3 Jen Rock Country Island (not in GOM) 6/17 - 6/20 N 581 1.18 28 0.22 1, 3 Jen Rock Season Total N 18 1.60 5 0.22 3 Jen Rock 2016 NS COAST TOTAL 619 50 2015 NS COAST TOTAL 687 0 35 0 0 2014 NS COAST TOTAL 651 44 38 0 0 2013 NS COAST TOTAL 596 50 38 0 0 2012 NS COAST TOTAL 574 50 34 0 0 2011 NS COAST TOTAL 631 60 38 0 0 2010 NS COAST TOTAL 632 54 38 0 0 * Data for The Brothers is reported as total count, with 38 roseates. 2009 NS COAST TOTAL 473 42 42 0 0 2008 NS COAST TOTAL 527 28 55 0 0 NEW BRUNSWICK ISLAND NAME DATE METHOD COTE ARTE ROST LETE LAGU FLEDGE/NEST N SD METHOD EGGS/NEST N SD OBSERVER Machias Seal Season Total NP 175 0.55 (ARTE only) 54 (ARTE only) 2,3 1.52 (ARTE only)4 (ARTE on 0.60 Stefanie Collar 2016 NB COAST TOTAL A tern census was not conducted this year, but it is estimated that there were up to 175 attempted nests island-wide, with a 2015 NB COAST TOTAL 9 141 0 0 0 probable species distribution of 94% ARTE and 6% COTE, similar to last year. -

Charles Hopkinson – the Innocent

Charles s. h opkinson The Innocent Eye Charles Hopkinson’s Studio at “Sharksmouth” Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts Photograph by Charles R. Lowell Charles s. h opkinson (1869-1962) The Innocent Eye June 8-July 20, 2013 V ose Fine American Art for Six Generations Est 1841 G alleries llc introduCtion Vose Galleries is pleased to present our fifth one-man exhibition of works by Boston painter Charles Sydney Hopkinson (1869-1962), most of which have come directly from the Hopkinson family and have never before been offered for sale. We present fifteen watercolors and fifteen oil paintings, including the powerful cover work, Yacht Races , which illustrates Hopkinson’s life long search for new methods and ideas in the making of art. Unlike most of his Boston con - temporaries who studied and taught at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Hopkinson chose a different approach. He studied at the Art Students League in New York City, whose instructors followed a less dogmatic method of teaching. The artist also made several trips to Europe, where he viewed exciting new forms of self-expression. He was one of only a few Boston artists to be invited to show work in the avant-garde International Exhibition of Modern Art in New York City in 1913, which exposed audiences to the radical art movements taking place in Europe, particularly in France. Now cel - ebrating its one-hundredth year anniversary, the exhi - bition, which is now commonly referred to as the Armory Show of 1913, has become a watershed in the history of modernism in the United States. -

THE Official Magazine of the OCEANOGRAPHY SOCIETY

OceThe OFFiciala MaganZineog OF the Oceanographyra Spocietyhy CITATION Dybas, C.L. 2011. Ripple marks—The story behind the story.Oceanography 24(3):8–13, http://dx.doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2011.84. COPYRIGHT This article has been published inOceanography , Volume 24, Number 3, a quarterly journal of The Oceanography Society. Copyright 2011 by The Oceanography Society. All rights reserved. USAGE Permission is granted to copy this article for use in teaching and research. Republication, systematic reproduction, or collective redistribution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] or The Oceanography Society, PO Box 1931, Rockville, MD 20849-1931, USA. doWnloaded From WWW.tos.org/oceanography Ripple Marks The Story Behind the Story by CHeryL Lyn Dybas THE GULF of Maine: Between A RocK and A Hard PLace? Slack Tide for Seabirds To understand the shore, it is not enough to stand like sentinels, their craggy granite faces cliff. My gaze drifts meter by meter along an catalogue its life. Understanding comes only inviting—if you’re a seabird. For hundreds old wooden railway, its rockweed-covered when we can sense the long rhythms of earth upon hundreds of Atlantic puffins, guil- planks stretching from the waterline to a and sea that sculptured its land forms and lemots, razorbills, and other birds of the lighthouse perched high above. The railway produced the rock and sand of which it is open ocean, the welcome mat is out. The once carried supplies up and down the steep composed; when we can sense with the eye birds spend their summers on the islands, edge. -

Beverly Gloucester

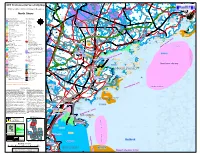

, "! k o W PINTAIL ro W S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S + S S S S S S S B POND THOMPSON "! e f W FOX i W MOUNTAIN ew ESSEX l ISLAND Þ VINEYARD Softshell clam A S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S!S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S 0 W S S S S S S S S S S MILL S S S S S S S B PINE HILL 0"! W POND R CRAFT HILL "! A ISLAND RIVERVIEW D , +0 W STRANGMAN S "! "! "! POND W T W S S S S S S S S S TOPSFIS SES S SLS SDS SÞR S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S SUNSET S S S S S S S !E SAGAMORE HILL GLOUCESTER R E HILL I T O H V R W S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S ILS S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S TURF MEADOW S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S SE S ive L SOUTH ESSEX S Ipswich R r E RAILCUT HILL R RIVERVIEW LANDING F k N i o , O DEP Environmental Sensitivity Map s COLT CANDLEWOOD EVELETH HILL ro S h "! S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S B S S S S S S S S S S Softshell clam S S S SB S S S B e A roo ISLAND SAVIN if B k w OAK ISLAND BUNKER le Þ W TURHKEY AMILHTILL ON A ! W MEADOWS S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S ISSLANDS S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S SWS S S S S S S S S S S S S W 0 E "! , ESSEX FALLS S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S -

Oral History Interview with Allan Rohan Crite, 1979 January 16-1980 October 22

Oral history interview with Allan Rohan Crite, 1979 January 16-1980 October 22 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Allan Rohan Crite on January 16, 1979 and culminating on October 22, 1980. The interview was conducted by Robert Brown for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview [TAPE 1, SIDE 1] Note: Susan Thompson, associate of Crite, participated in interview of Oct. 22. ALLAN ROHAN CRITE I was born March 20, 1910, at 190 Grove Street, North Plainfield, NJ. As far as my memory of the place is concerned, I'll be a little bit vague because I left there when I was less than a year old, and came to Boston. But I did go back just recently, during the month of December, so I had a chance to see my birthplace -- the house is still standing. It's a funny little two-storey frame house, on a tree-lined street. ROBERT BROWN: Why did your parents bring you up here [Boston]? ALLAN ROHAN CRITE Well, I brought my parents to Boston (both laugh). I really don't know, exactly. My father was studying at Cornell University, and then I think he came and went to the University of Vermont. I think my mother, when she came to Boston, worked out in Danvers for some wealthy family there.