Istory of the Nstitutevolume 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Champagnat Journal Contribute to Our Seeking; to As Well As How We Respond to Those Around Us

OCTOBER 2015 Vocation Engagement Spirituality AN INTERNATIONAL MARIST JOURNAL OF CHARISM IN EDUCATION volume 17 | number 03 | 2015 Inside: • Standing on the Side of Mercy • Marist Icons: essential to our Life and Mission Champagnat: An International Marist Journal of Charism in Education aims to assist its readers to integrate charism into education in a way that gives great life and hope. Marists provide one example of this mission. Editor Champagnat: An International Marist Journal of Tony Paterson FMS Charism in Education, ISSN 1448-9821, is [email protected] published three times a year by Marist Publishing Mobile: 0409 538 433 Peer-Review: Management Committee The papers published in this journal are peer- reviewed by the Management Committee or their Michael Green FMS delegates. Lee McKenzie Tony Paterson FMS (Chair) Correspondence: Roger Vallance FMS Br Tony Paterson, FMS Marist Centre, Peer-Reviewers PO Box 1247, The papers published in this journal are peer- MASCOT, NSW, 1460 reviewed by the Management Committee or their Australia delegates. The peer-reviewers for this edition were: Email: [email protected] Michael McManus FMS Views expressed in the articles are those of the respective authors and not necessarily those of Tony Paterson FMS the editors, editorial board members or the Kath Richter publisher. Roger Vallance FMS Unsolicited manuscripts may be submitted and if not accepted will be returned only if accompanied by a self-addressed envelope. Requests for permission to reprint material from the journal should be sent by email to – The Editor: [email protected] 2 | ChAMPAGNAT OCTOBER 2015 Champagnat An International Marist Journal of Charism in Education Volume 17 Number 03 October 2015 1. -

Cutting Patterns in DW Griffith's Biographs

Cutting patterns in D.W. Griffith’s Biographs: An experimental statistical study Mike Baxter, 16 Lady Bay Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 5BJ, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]) 1 Introduction A number of recent studies have examined statistical methods for investigating cutting patterns within films, for the purposes of comparing patterns across films and/or for summarising ‘average’ patterns in a body of films. The present paper investigates how different ideas that have been proposed might be combined to identify subsets of similarly constructed films (i.e. exhibiting comparable cutting structures) within a larger body. The ideas explored are illustrated using a sample of 62 D.W Griffith Biograph one-reelers from the years 1909–1913. Yuri Tsivian has suggested that ‘all films are different as far as their SL struc- tures; yet some are less different than others’. Barry Salt, with specific reference to the question of whether or not Griffith’s Biographs ‘have the same large scale variations in their shot lengths along the length of the film’ says the ‘answer to this is quite clearly, no’. This judgment is based on smooths of the data using seventh degree trendlines and the observation that these ‘are nearly all quite different one from another, and too varied to allow any grouping that could be matched against, say, genre’1. While the basis for Salt’s view is clear Tsivian’s apparently oppos- ing position that some films are ‘less different than others’ seems to me to be a reasonably incontestable sentiment. It depends on how much you are prepared to simplify structure by smoothing in order to effect comparisons. -

Constitutions and Statutes CONSTITUTIONS and STATUTES CONSTITUTIONS Institute of the Marist Brothers ISBN 979-12-80249-01-2

Constitutions and Statutes CONSTITUTIONS AND STATUTES CONSTITUTIONS Institute of the Marist Brothers ISBN 979-12-80249-01-2 9 791280 249012 Cover_EN_Costitu.indd 1 08/06/21 16:24 COSTITUZIONE_EN_DEF.indd 1 31/05/21 09:15 COSTITUZIONE_EN_DEF.indd 2 31/05/21 09:15 Constitutions and Statutes Institute of the Marist Brothers COSTITUZIONE_EN_DEF.indd 3 31/05/21 09:15 Institute of the Marist Brothers © Casa Generalizia dei Fratelli Maristi delle Scuole P.le Marcellino Champagnat, 2 00144 Rome – Italy [email protected] www.champagnat.org Production: Communications Department of General Administration June 2021 Constitutions and Statutes of the Marist Brothers / Institute of the Marist Brothers. C758 – Rome : Casa Generalizia dei Fratelli Maristi delle Scuole Fratelli Maristi, 2021. 2021 224 p. ; 19 cm ISBN 979-12-80249-01-2 1. Marist Brothers - Statutes. 2. Constitutions. 3. Missionaries – Vocation. CDD. 20. ed. – 271 Sônia Maria Magalhães da Silva - CRB-9/1191 Sistema Integrado de Bibliotecas – SIBI/PUCPR COSTITUZIONE_EN_DEF.indd 4 31/05/21 09:15 FOREWORD 7 APPROVAL DECREE OF 2020 11 CHAPTER I OUR RELIGIOUS INSTITUTE of BROTHERS IDENTITY OF THE MARIST BROTHER IN THE CHURCH 15 CHAPTER II OUR IDENTITY AS RELIGIOUS BROTHERS Institute of the Marist Brothers CONSECRATION AS BROTHERS 25 © Casa Generalizia dei Fratelli Maristi delle Scuole P.le Marcellino Champagnat, 2 A) EVANGELICAL COUNSEL OF CHASTITY 28 00144 Rome – Italy B) EVANGELICAL COUNSEL OF OBEDIENCE 32 [email protected] C) EVANGELICAL COUNSEL OF POVERTY 35 www.champagnat.org Production: Communications Department of General Administration June 2021 CHAPTER III OUR LIFE AS BROTHERS LIFE IN THE INSTITUTE 43 A) FRATERNAL LIFE IN COMMUNITY 44 B) CULTIVATING SPIRITUALITY 53 C) SENT ON MISSION 61 Constitutions and Statutes of the Marist Brothers / Institute of the Marist Brothers. -

Low-Res-Fourvière and Lyon Booklet-4 Print Ready

2015 2016 Fourvière Our Lady of Fourvière and Lyon Our Lady of Fourvière and Lyon Now that same day two of them were going to a village called Emmaus, about seven miles from Jerusalem. They were talking with each other about everything that had happened. As they talked and discussed these things with each other, Jesus himself came up and walked along with them; but they were kept from recognizing him. He asked them, “What are you discussing together as you walk along?” They stood still, their faces downcast. One of them, named Cleopas, asked him, “Are you the only one visiting Jerusalem who does not know the things that have happened there in these days?” “What things?” he asked. “About Jesus of Nazareth,” they replied. “He was a prophet, powerful in word and deed before God and all the people. The chief priests and our rulers handed him over to be sentenced to death, and they crucified him; but we had hoped that he was the one who was going to redeem Israel. And what is more, it is the third day since all this took place. In addition, some of our women amazed us. They went to the tomb early this morning but didn’t find his body. They came and told us that they had seen a vision of angels, who said he was alive. Then some of our companions went to the tomb and found it just as the women had said, but they did not see Jesus.” He said to them, “How foolish you are, and how slow to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Did not the Messiah have to suffer these things and then enter his glory?” And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he explained to them what was said in all the Scriptures concerning himself. -

U.S. Catholic Mission Handbook 2006

U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org Additional copies may be ordered from USCMA. USCMA 3029 Fourth Street., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202-884-9764 Fax: 202-884-9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org COST: $4.00 per copy domestic $6.00 per copy overseas All payments should be prepaid in U.S. dollars. Copyright © 2006 by the United States Catholic Mission Association, 3029 Fourth St, NE, Washington, DC 20017-1102. 202-884-9764. [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE UNITED STATES CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION (USCMA)Purpose, Goals, Activities .................................................................................iv Board of Directors, USCMA Staff................................................................................................... v Past Presidents, Past Executive Directors, History ..........................................................................vi Part II: The U.S. -

Historical Sources of Marist Spirituality

Historical sources of Marist spirituality Br. Michael Green This text comprises a series of articles written in 2020 by Marist historian and spiritual writer, Br Michael Green, on the theme of Marist spirituality. Br Michael takes the six characteristics of our spirituality that are named in ‘Water from the Rock’ and explores their historical and spiritual sources, relating them to the situations of today’s Marists. The articles were written for the Australian online Marist newsletter ‘Christlife’, and were also published in the education journal ‘Champagnat’. Introduction Marcellin Champagnat didn’t know anything about Marist spirituality, or about any kind of spirituality for that matter. What? No, there’s no myth-busting exposé to follow. Please, stay calm and keep reading. The term ‘spirituality’ has not been around for long, just over a hundred years or so. The word, as a noun, would have been unknown to Marcellin. It emerged in France towards the end of the nineteenth century, and grew in common usage in the second half of the twentieth, helped not insignificantly by the assiduous compiling, between 1928 and 1995, of a mammoth ten-volume academic work called the Dictionnaire de Spiritualité. Begun by a small team of French Jesuits, its 1500 contributors came to include many of the leading theologians and masters of the spiritual life of the twentieth century. The concept of ‘spirituality’ (singular and plural) took its place in mainstream religious discourse. Today its breadth and grab is wide, covering not only traditional paths of the Christian spiritual life, but also those of non-Christian traditions, and indeed non-theist ways of experiencing and understanding life and the cosmos. -

A Book of Texts for the Study of Marist Spirituality

edwin l. keel, s.m. a book of texts for the study of marist spirituality 2 a book of texts for the study of marist spirituality compiled by edwin l. keel, s.m. ROME CENTER FOR MARIST STUDIES 1993 3 The call of Colin is to an adventure. John Jago, S.M., Mary Mother of our Hope 4 Introduction This book is an offshoot of the courses in Marist Spirituality that I have been offering since 1986 at the Center for Marist Studies in Rome and the Marist House in Framingham, and in 1992 at St. Anne’s Presbytery in London. In 1991 I decided that the mélange of photocopied English translations of texts that I was using then needed to be expanded. I also wished to make the texts available in their original languages. These will be found in the French edition. Because the book is structured around the three symbolic moments of Fourvière, Cerdon and Bugey, which the Constitutions of 1988 offer as the framework both for Marist formation and for the whole of Marist life, the book should be of use not only for Marist renewal programs, but for those involved in Marist initial formation and for any Marist who seeks a deeper grasp of Marist spirituality through a thematic study of texts significant in our spiritual tradition. The texts are collected and presented here with little or no commentary. It is for the reader to meet Colin and the other founders and early Marists in their own words, and to let those words open up new paths of insight, of feeling and of action. -

"Our Own Flesh and Blood?": Delaware Indians and Moravians in the Eighteenth-Century Ohio Country

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 "Our Own Flesh and Blood?": Delaware Indians and Moravians in the Eighteenth-Century Ohio Country. Jennifer L. Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Miller, Jennifer L., ""Our Own Flesh and Blood?": Delaware Indians and Moravians in the Eighteenth- Century Ohio Country." (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8183. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8183 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Our Own Flesh and Blood?”: Delaware Indians and Moravians in the Eighteenth-Century Ohio Country Jennifer L. Miller Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences At West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Tyler Boulware, Ph.D., chair Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Brian Luskey, Ph.D. Rachel Wheeler, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: Moravians, Delaware Indians, Ohio Country, Pennsylvania, Seven Years’ War, American Revolution, Bethlehem, Gnadenhütten, Schoenbrunn Copyright 2017 Jennifer L. -

The Marists in Aleppo 1904 - …

The Marists in Aleppo 1904 - …... The beginnings In August 1904, four Marist Brothers arrived in Aleppo to run the school for Armenian Catholics in Telal Street. Later, they worked with the Greek Catholics by running the school of Saint Nicholas and with the Jesuits in their school in the old city. In 1932, they built their own school, Champagnat College, in Fayçal Street (currently called Georges Salem School). In 1948 they moved to the section of the city called Mohafzat. Since 1967, when the college was nationalised, they have worked with the Amal School. Their presence has been in the areas of the scouts, catechesis, the accompaniment of young people and in solidarity with the poor. In August 2004, the centenary of the presence of the Marist Brothers in Aleppo is being celebrated. The group Champagnat-Brothers has educated hundreds of young people in the Marist spirit through scouting since 1976 until today. The group Champagnat-Jabal (referring to the neighbourhood of Jabal el Saydé) was started first. Some young people, feeling the urgency of a Marist scouting education in the poorer neighbourhoods, dared to start a group for the children of this neighbourhood. Brothers and young people are continuing with this project in a spirit of enthusiasm and hope. P r o m i s e Beginning of the year C h r I s t m a s P a R t y End of the year Ceremony Champagnat Marist Family Movement Several lay people have participated in Marist formation sessions in Europe. On their return, they invited couples to form the “Champagnat Marist Family Movement”. -

The Making of Marist Men Welcome to Sacred Heart College

The Making of Marist Men Welcome to Sacred Heart College Dear Parents We welcome your interest in Sacred Heart College. This prospectus provides an introduction to our school – past and present; insight into its special character; and an overview of our academic, sporting, music and cultural curricula. A Sacred Heart Sacred Heart College has evolved education provides a through the vision and dedication of many Marist Brothers, who foundation of faith and still have a real and valued the determination to presence in the life of our school. We inspire our students to be succeed at the highest the very best that they can be, level in personal and to make something special of professional life. themselves, no matter what their talents are, through: • The nurturing of faith, within the context of the Catholic, Marist and Champagnat community • A dedication to academic learning by taking advantage of the opportunities offered through our academic curriculum, and developing excellence through our Academic Institute • Embracing the arts with our state-of-the-art music and drama facilities and specialist teaching in our Music Institute • A passion for sport, including the chance to apply for specialist coaching through our Sports Institute. We value parental input and endeavour to work closely with you. Together, we can work to ensure we achieve our vision for each student effectively – a grounding in the Catholic faith, preparation for the challenges of the future, and the confidence and resilience to succeed in an ever- changing and challenging world. For further information about Sacred Heart College, please visit our website www.sacredheart.school.nz Jim Dale Principal The foundations and history of Sacred Heart College Our founder A prime site for a remarkable school St Marcellin Champagnat was born on 20 May Students at Sacred Heart 1789 in the hamlet of Le Rosey, near Marlhes College enjoy one of the best in France. -

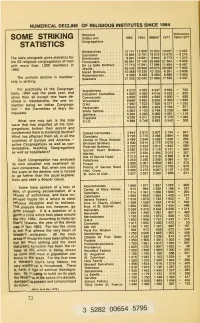

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

The Source and the Stream

Saint Marcellin Champagnat and Venerable Brother François THE SOURCE AND THE STREAM WORD OF INTRODUCTION The Source and the Stream is a kind of parallel between our Founder, Marcellin Champagnat (the source), and Brother François who was to be his first successor, “his living portrait”. Our Congregation, under Brother François, experienced an astonishing growth: the source be- came the stream. Father Champagnat and Brother François lived the same story, the same beginnings, shared the same ideal, the same charism, the same journey towards holiness.These pages focus on these two people to- gether so that the Brothers may grow in their affection, enthusiasm and gratitude for them. Though they were two entirely different personalities, they worked together as closely as possible. Holiness is first of all the work of the Spirit who marks each person with patience and intelligence; it is al- so one’s heart and life being overcome by the power of the resurrec- tion of the Lord. But Marcellin and François clearly demonstrate that you can journey towards God using your own natural, different gifts. The style is meant to be light consisting of summaries and short texts. Perhaps these pages can strengthen in our family the custom of ex- tending to our first Brothers and to all the Brothers who have pre- ceded us that same spontaneous and strong affection that we show our Father and Founder, Marcellin Champagnat. Pride in our origins consolidates the present day Marist identity. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS SAINT MARCELLIN CHAMPAGNAT VENERABLE BROTHER FRANÇOIS Among the blessings deriving from his family, Among the blessings deriving from his family, an exceptional father .