Utah Jazz, a Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Al-Tally” Ascension Journey from an Egyptian Folk Art to International Fashion Trend

مجمة العمارة والفنون العدد العاشر “Al-tally” ascension journey from an Egyptian folk art to international fashion trend Dr. Noha Fawzy Abdel Wahab Lecturer at fashion department -The Higher Institute of Applied Arts Introduction: Tally is a netting fabric embroidered with metal. The embroidery is done by threading wide needles with flat strips of metal about 1/8” wide. The metal may be nickel silver, copper or brass. The netting is made of cotton or linen. The fabric is also called tulle-bi-telli. The patterns formed by this metal embroidery include geometric figures as well as plants, birds, people and camels. Tally has been made in the Asyut region of Upper Egypt since the late 19th century, although the concept of metal embroidery dates to ancient Egypt, as well as other areas of the Middle East, Asia, India and Europe. A very sheer fabric is shown in Ancient Egyptian tomb paintings. The fabric was first imported to the U.S. for the 1893 Chicago. The geometric motifs were well suited to the Art Deco style of the time. Tally is generally black, white or ecru. It is found most often in the form of a shawl, but also seen in small squares, large pieces used as bed canopies and even traditional Egyptian dresses. Tally shawls were made into garments by purchasers, particularly during the 1920s. ملخص البحث: التمي ىو نوع من انواع االتطريز عمى اقمشة منسوجة ويتم ىذا النوع من التطريز عن طريق لضم ابر عريضة بخيوط معدنية مسطحة بسمك 1/8" تصنع ىذه الخيوط من النيكل او الفضة او النحاس.واﻻقمشة المستخدمة في صناعة التمي تكون مصنوعة اما من القطن او الكتان. -

Nancy Wilson Ross

Nancy Wilson Ross: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Ross, Nancy Wilson, 1901-1986 Title: Nancy Wilson Ross Papers Dates: 1913-1986 Extent: 261.5 document boxes, 12 flat boxes, 18 card boxes, 7 galley folders (138 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this American writer encompass her entire literary career and include manuscript drafts, extensive correspondence, and subject files reflecting her interest in Eastern cultures. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03616 Language: English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1972 (R5717) Provenance Ross's first shipment of materials to the Ransom Center accompanied her husband Stanley Young's papers, and consisted of Ross's literary output to 1975, including manuscripts, publications, and research materials. The second, posthumous shipment contained manuscripts created since 1974, and all her correspondence, personal, and financial files, as well as files concerning the estate of Stanley Young. Processed by Rufus Lund, 1992-93; completed by Joan Sibley, 1994 Processing note: Materials from the 1975 and 1986 shipments are grouped following Ross's original order, with the exception of pre-1970, special, and current correspondence which were interfiled during processing. An index of selected correspondents follows at the end of this inventory. Repository: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin Ross, Nancy Wilson, 1901-1986 Manuscript Collection MS-03616 2 Ross, Nancy Wilson, 1901-1986 Manuscript Collection MS-03616 Biographical Sketch Nancy Wilson was born in Olympia, Washington, on November 22, 1901. She graduated from the University of Oregon in 1924, and married Charles W. -

Communications Big 12 Championship 19-8 12-6 #11 / #12 46-12 32-8 11 Overall Big 12 Ranking (Ap/Coaches) Big 12 Champ

MARCH 11, 2021 | BIG 12 CHAMPIONSHIP - QUARTERFINALS | GAME NOTES KANSAS COMMUNICATIONS BIG 12 CHAMPIONSHIP 19-8 12-6 #11 / #12 46-12 32-8 11 OVERALL BIG 12 RANKING (AP/COACHES) BIG 12 CHAMP. UNDER BILL SELF BIG 12 CHAMP. TITLES AT Bill Self 520-117 (.816) T-Mobile Center 24-5 (.828) JAYHAWKS HEAD COACH RECORD AT KU, 18TH SEASON 2021 VENUE CHAMP. RECORD AT T-MOBILE CENTER GAME SCHEDULE (H: 13-1; A: 4-6; N: 2-1) KANSAS VS OKLAHOMA / IOWA STATE KU-OSU SERIES AT A GLANCE KU OPP Big 12 Championship • Quarterfinals OVERALL KANSAS LEADS, 151-69 Date Rnk Rnk Opponent TV Time/Result Kansas City, Mo. • T-Mobile Center (18,972) in Big 12 Champ. (T-Mobile Center) Tied, 2-2 (0-0) NOVEMBER (1-1) 28 Thursday, March 11, 2020 • 5:30 p.m. (CT) Last Meeting L, 68-75 @ OU, 1/23/21 26 6/52 1/ Gonzaga% FOX L, 90-102 27 6/5 -/- Saint Joseph’s% FS1 W, 94-72 KU-ISU SERIES AT A GLANCE ESPN / ESPN2 JAYHAWK RADIO NETWORK OVERALL KANSAS LEADS, 186-66 DECEMBER (7-0) Play-by-Play: Bob Wischusen Radio: IMG Jayhawk Radio Network in Big 12 Champ. (T-Mobile Center) Tied, 3-3 (1-3) 1 7/5 20/9 Kentucky# ESPN W, 65-62 Analyst: Fran Fraschilla Webcast: KUAthletics.com/Radio Last Meeting W, 64-50 @ ISU, 2/11/21 3 7/5 -/- WASHBURN B12 NOW W, 89-54 Reporter: Holly Rowe Play-by-Play: Brian Hanni Producer: Scott Gustafson Analyst: Greg Gurley RANKINGS 5 7/5 -/- NORTH DAKOTA ST. -

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks Honoring the 2009 Major League Soccer Champion Real Salt Lake June 4, 2010

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks Honoring the 2009 Major League Soccer Champion Real Salt Lake June 4, 2010 Hello, everybody. Please have a seat. Well, welcome to the White House. And congratulations on winning your first MLS Cup championship and for bringing the State of Utah its first professional sports title in almost 40 years. That's a pretty big deal. You can give them a round of applause for that again. I want to acknowledge the Senator from the great State of Utah, Senator Bennett, who is here. He is incredibly proud of this team—too tall to play soccer. [Laughter] I want to congratulate Dave Checketts for his leadership and for dedicating his career to expanding the world of professional sports. And, of course, I want to congratulate the players and coaches from Real Salt Lake. I know that this team had a pretty unlikely journey to get here. You qualified for the playoffs on the last day of the season with a losing record. [Laughter] That's cutting it a little close, guys. [Laughter] You beat your biggest rival, took down the defending champions on your way to the title game. And with the cup on the line, you held two of the game's biggest stars scoreless in regulation and went on to win in a shootout, all of which goes to show that in Major League Soccer, there's no such thing as a foregone conclusion. Now, you did it because, in the words of Coach Kreis—and I have to say this is one of the rare coaches that I see in these events who I think might be able to still play—[laughter]—he looks very fit. -

Cardinal Tradition Louisville Basketball

Cardinal Tradition Louisville Basketball Louisville Basketball Tradition asketball is special to Kentuckians. The sport B permeates everyday life from offices to farm- lands, from coal mines to neighborhood drug stores. It is more than just a sport played in the cold winter months. It is a source of pride filled year-round with anticipation, hope and celebration. Kentuckians love their basketball, and the tradition-rich University of Louisville program has supplied its fans with one of the nation’s finest products for decades. Legendary coach Bernard “Peck” Hickman, a Basketball Hall of Fame nominee, arrived on the UofL campus in 1944 to begin a remarkable string of 46 consecutive winning seasons. For 23 seasons, Hickman laid an impressive foundation for UofL. John Dromo, an assistant coach under Hickman for 19 years, continued the Louisville program in outstanding fashion following Hickman’s retirement. For 30 years, Denny Crum followed the same path of success that Hickman and Dromo both walked, guiding the Cardinals to even higher acclaim. Now, Coach Rick Pitino energized a re-emergence in building upon the rich UofL tradition in his 16 years, guiding the Cardinals to the 2013 NCAA championship, NCAA Final Fours in 2005 and 2012 and the NCAA Elite Eight five of the past 10 sea- sons. Among the Cardinals’ past successes include national championships in the NCAA (1980,1986, 2013), NIT (1956) and the NAIB (1948). UofL is Taquan Dean kisses the Freedom Hall floor Tremendous pride is taken in the tradition the only school in the nation to have claimed the after his final game as a Cardinal. -

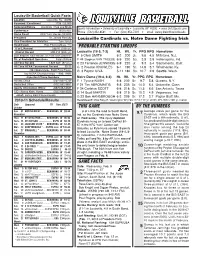

Probable Starting Lineups This Game by the Numbers

Louisville Basketball Quick Facts Location Louisville, Ky. 40292 Founded / Enrollment 1798 / 22,000 Nickname/Colors Cardinals / Red and Black Sports Information University of Louisville Louisville, KY 40292 www.UofLSports.com Conference BIG EAST Phone: (502) 852-6581 Fax: (502) 852-7401 email: [email protected] Home Court KFC Yum! Center (22,000) President Dr. James Ramsey Louisville Cardinals vs. Notre Dame Fighting Irish Vice President for Athletics Tom Jurich Head Coach Rick Pitino (UMass '74) U of L Record 238-91 (10th yr.) PROBABLE STARTING LINEUPS Overall Record 590-215 (25th yr.) Louisville (18-5, 7-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Asst. Coaches Steve Masiello,Tim Fuller, Mark Lieberman F 5 Chris SMITH 6-2 200 Jr. 9.8 4.5 Millstone, N.J. Dir. of Basketball Operations Ralph Willard F 44 Stephan VAN TREESE 6-9 220 So. 3.5 3.9 Indianapolis, Ind. All-Time Record 1,625-849 (97 yrs.) C 23 Terrence JENNINGS 6-9 220 Jr. 9.3 5.4 Sacramento, Calif. All-Time NCAA Tournament Record 60-38 G 2 Preston KNOWLES 6-1 190 Sr. 14.9 3.7 Winchester, Ky. (36 Appearances, Eight Final Fours, G 3 Peyton SIVA 5-11 180 So. 10.7 2.9 Seattle, Wash. Two NCAA Championships - 1980, 1986) Important Phone Numbers Notre Dame (19-4, 8-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Athletic Office (502) 852-5732 F 1 Tyrone NASH 6-8 232 Sr. 9.7 5.8 Queens, N.Y. Basketball Office (502) 852-6651 F 21 Tim ABROMAITIS 6-8 235 Sr. -

Communications

MARCH 23, 2019 | NCAA TOURNAMENT - SECOND ROUND | GAME NOTES KANSAS COMMUNICATIONS # # # # 26-9 12-6 17 / 17 27-9 11-7 14 / 18 TIGERS OVERALL BIG 12 RANKING (AP/COACHES) OVERALL SEC RANKING (AP/COACHES) -VS- Bill Self 473-105 (.818) Bruce Pearl 97-71 (.577) JAYHAWKS HEAD COACH RECORD AT KU, 16TH SEASON HEAD COACH RECORD AT AU, FIFTH SEASON SCHEDULE (H: 17-0; A: 3-8; N: 6-1) GAME (4) KANSAS VS (5) AUBURN KU IN THE NCAA TOURNEY (More on pg. 49) KU OPP NCAA Championship • Second Round OVERALL (under Bill Self) 108-46 (38-14) Rnk Rnk Opponent TV Time/Result Salt Lake City, Utah • Vivint Smart Home Arena (18,284) as No. 4 seed 8-4 NOVEMBER (5-0) 36 In Round of 32 (Since 1981) 23-10 6 1/1 10/10 vs. Michigan State! ESPN W, 92-87 Saturday, March 23, 2019 • 8:40 p.m. (CT) 12 2/1 -/- VERMONT~ ESPN2 W, 84-68 16 2/1 -/- LOUISIANA JTV/ESPN+ W, 89-76 TBS JAYHAWK RADIO 21 2/2 rv/rv vs. Marquette# ESPN2 W, 77-68 NETWORK Play-by-Play: Andrew Catalon Radio: IMG Jayhawk Radio Network 23 2/2 5/5 vs. Tennessee# ESPN2 W, 87-82 ot Analysts: Steve Lappas Webcast: KUAthletics.com/Radio DECEMBER (6-1) Reporter: Lisa Byington Play-by-Play: Brian Hanni POINTS 1 2/2 -/- STANFORD ESPN W, 90-84 ot Producer: Johnathan Segal Analyst: Greg Gurley 75.7 PER GAME ›› 79.5 4 2/2 -/- WOFFORD JTV/ESPN+ W, 72-47 Director: Andy Goldberg Producer/Engineer: Steve Kincaid 8 2/2 -/- NEW MEXICO STATE^ ESPN2 W, 63-60 TIP-OFF 46.5 ‹‹ FG% 44.8 15 1/1 17/16 VILLANOVA ESPN W, 74-71 • Kansas is making its 48th NCAA Tournament appearance and has a 18 1/1 -/- SOUTH DAKOTA JTV/ESPN+ W, 89-53 108-46 record in the event. -

ACADEMIC FOCUS Thunderbird M En Cross Country Runners Won the Cal Poly Bronco Invitational Saturday

I T y CAMPUS SPORTS: The ACADEMIC FOCUS Thunderbird m en cross country runners won the Cal Poly Bronco Invitational Saturday. PAGE 13. 'Law and Beyond Law; CAMPUS NEWS: SUU's NATIONAL NEWS: New Peace and Justice,' is the ~ University Centers serve many wildfires empted yesterday in topic Thursday. i who can't make it to Cedar City California-this time in San every day. PAGE 3. Bernardino County. PAGE 6. PAGE 10. CAMPUS ARTS: SUU's NAT'L SPORTS: It wasn't Noel Neeb is quickly becoming much of a showdown yesterday as one of the theatre department's the Cowboys gave Jimmy Johnson Edwin Firmage busiest actors.PAGE 12. his comeuppance. PAGE 18. I ALMANAC • October 28 &. 29, satellite voter registration, IN THUNDERBIRD CIRCLE DINING: Cedar City Public Library, final chance to register for the Nov. 5 elections. Lunch (11-1:30): Meatballs and country gravy, October vegetarian lasagna, french toast stix, soup &. salad • Influenza immunizations available at SUU Student bar, grill, deli. Health Service Clinic located in the Centrum, · room 220 (8:30 a.m. to 9:20 a.m.), or in Manzanita Dinner (5-6:30): Deluxe tostado, turkey steak, soup &. C-1 (9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.). Cost of immunization is salad bar, grill, deli. $8. WEATHER FORECAST: • Sigma Nu Eigth Annual Haunted House, 197 S. 300 W. 7-11 p.m. SNOW HIGH: Low 40s LOW: High 20s • October 28 &. 29, satellite voter registration, Cedar IN THUNDERBIRD CIRCLE DINING: City Public Library, final chance to register for the Nov. 5 elections. -

Bkm-Release-2021-02-14 (At Wisconsin).Indd

HAIL! TO THE VICTORS VALIANT | hail! to the conqu‘ring heroes | HAIL! HAIL! TO MICHIGAN | the leaders and best! UUNIVERSITYN I V E R S I T Y OOFF MMICHIGANI C H I G A N GAME DAY BBASKETBALLA S K E T B A L L NOTEBOOK 2020-21 MICHIGAN BASKETBALL | 2020-21 RATING SOS Overall 13-1 Big Ten 8-1 NCAA Net: 3rd - Home 10-0 Home 5-0 KenPom: 3rd 44th Away 3-1 Away 3-1 Sagarin: 3rd 49th Neutral 0-0 Neutral 0-0 ESPN’s BPI: 8th 68th Associated Press: 3rd (1,438) vs. Ranked: 3-1 GG1515 USA Today Coaches: 3rd (722) Weeks in Polls: 10 #3/3 MICHIGAN wolverines (13-1; 8-1 Big Ten) Regular Season Opponent Time/Results TV at #21/21 WISCONSIN badgers (15-6; 9-5 Big Ten) Wed., Nov. 25 BOWLING GREEN W 96-82 ESPN2 Sun., Nov. 29 OAKLAND W 81-71 OT B1G Network Game Day | Big Ten Road Match-up Wed., Dec. 2 BALL STATE W 84-65 B1G Network • Date: Sunday, February 14, 2021 Sun. Dec. 6 CENTRAL FLORIDA W 80-58 B1G Network • Tip: 12:02 p.m. CT / 1:02 p.m. ET Wed., Dec. 9 N.C. STATE (1) postponed (2) • Location: Madison, Wisconsin TOLEDO W 91-71 FS1 • Arena: Kohl Center (17,230) Sun., Dec. 13 PENN STATE+ W 62-58 B1G Network • TV Broadcast: CBS Sports Fri., Dec. 25 at Nebraska+ W 80-69 B1G Network Thu., Dec. 31 at Maryland+ W 84-73 ESPN • TV Talent: Kevin Harlan (play-by-play) & Bill Raftery (analyst) Sun., Jan. -

The Church and Scholars—Ten Years Later July 2003—$5.95 Two Perspectives by Lavina Fielding Anderson and Armand L

Cover_128.qxd 7/1/2003 4:41 PM Page 2 MORMON EXPERIENCE SCHOLARSHIP ISSUES & ART Center Insert Preliminary Program SUNSTONESUNSTONE 2003 SALT LAKE SUNSTONE SYMPOSIUM England essay contest winner MURKY PONDS AND LIGHTED PLACES by Carol Clark Ottesen (p.4) Sunstone History 1993 – 2001 by Gary James Bergera (p.24) Jana K. Riess on “R-rated movies that have helped me think about the gospel” (p.42) Can Gospel Doctrine lessons be interesting and build faith? Kathleen Petty reflects (p.45) “Stephen’s” story continued” by D. Jeff Burton (p.40) UPDATE Commemorating the priesthood revelation; Church relief efforts; Kirtland dedications; LDS book and film news; and more! (p.50) The Church and Scholars—Ten Years Later July 2003—$5.95 Two Perspectives by Lavina Fielding Anderson and Armand L. Mauss ifc.qxd 6/30/2003 9:02 PM Page 1 What is Sunstone? SINCE 1974, Sunstone has been a strong independent voice in Mormonism, exploring contemporary issues, hosting important discussions, and encouraging honest inquiry and exchange about Latter-day Saint experience and scholarship. THE ORGANIZATION’S flagship is SUNSTONE magazine, which comes out approximately five times per year. The Sunstone Education Foundation also sponsors a four-day symposium in Salt Lake City each summer and several regional symposiums in select cities throughout the year. See insert in this issue for information about this year’s Salt Lake Sunstone Symposium, 13–16 August. Special offer for new subscribers: *7 issues for the price of 6! Mail, phone, email, or fax your subscription request to: SUNSTONE: 343 N Third West, Salt Lake City, UT 84103; 801-355-5926; 801-355-4043 fax; [email protected]. -

Membership Directory

2015-2016 Membership Directory ESTABLISHED 1967 DEDICATED TO PRESERVE AND HONOR UTAH'S SPORTS HERITAGE _____ 3434 Bengal Blvd #106 Salt Lake City, Utah 84121 801-944-2379 www.utahsportshalloffame.org DIRECTORY CONTENTS History of the Hall of Fame Foundation 3 Executive Committee 4 Board of Directors 4 Emeritus Directors 4 Past Presidents 4 Hall of Fame Inductees 5 Distinguished Coaches 11 Coaches of Merit 14 Distinguished Service 14 Game Officials 16 Ream's Scholars 18 Member Directory 22 2 A SHORT HISTORY OF THE UTAH SPORTS HALL OF FAME FOUNDATION The Utah Sports Hall of Fame Foundation (USHOFF) was organized in 1967 as “The Old Time Athletes Association.” The goal then, as well as it is today, is to celebrate and preserve Utah’s storied sports heritage. In 1970, the Charter Class of 18 honorees was inducted into the Hall of Fame. Since then, a select number of administrators, coaches, players and prominent contributors to athletics in Utah have been inducted annually into the Hall of Fame. A beautifully-crafted plaque of recognition honoring each inductee is displayed in special display cases in the main concourse of the Energy Solutions Arena. In 1997, the organization officially changed its name to the current USHOFF. In 1972, the OTAA began honoring others who have made substantial contributions to the Utah sports community. The foundation started hosting annual and biannual recognition banquets for the following: 1. Distinguished Utah High School Head Coaches; 2. Utah “Coaches of Merit” (Head coaches who had spent many years in both high school and college); 3. Outstanding Game Officials in all sports from high school and college; 4. -

Opponents Nba Directory Nba Directory Eiw Eod History Records 16-17 Review Players Leadership

OPPONENTS NBA DIRECTORY NBA DIRECTORY LEADERSHIP PLAYERS 16-17 NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION CANADA NBA ENTERTAINMENT 50 Bay Street, Suite 1402, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5J 3A5 WOMEN’S NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCATION Telephone: . (416) 682-2000 Fax: ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� (416) 364-0205 NBA G LEAGUE NEW YORK ASIA/PACIFIC Olympic Tower, 645 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10022 Telephone: ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� (212) 407-8000 HONG KONG REVIEW RECORDS HISTORY Fax: �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������(212) 832-3861 Room 3101, Lee Gardens One, 33 Hysan Avenue, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Telephone: . .+852-2843-9600 NEW JERSEY Fax: �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� +852-2536-4808 100 Plaza Drive, Secaucus, NJ 07094 Telephone: ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� (201) 865-1500 TAIWAN Fax: �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������(201) 974-5973 Suite 1303, No. 88, Section 2, Chung Hsiao East Road, Taipei, Taiwan ROC 100 Telephone: