Emerging Paradigm of the Indian Ocean: Arihant’S Prowl and Its Regional Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 2018 Volume 09 Issue 02 Promoting Bilateral Relations | Current Affairs | Trade & Economic Affairs | Education | Technology | Culture & Tourism ABC Certified

Monthly Magazine on National & International Political Affairs, Diplomatic Issues February 2018 Volume 09 Issue 02 Promoting Bilateral Relations | Current Affairs | Trade & Economic Affairs | Education | Technology | Culture & Tourism ABC Certified “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE , Central Africa, Central Asia & Asia Pacific” Member APNS Central Media List A Largest, Widely Circulated Diplomatic Magazine | www.diplomaticfocus.org | www.diplomaticfocus-uk.com | Member Diplomatic Council /diplomaticfocusofficial /DFocusOfficial will benefit President of Indonesia H.E. Ir. H. Joko Widodo February 2018 Volume 09 Issue 02 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE ” 08 18 24 40 08 Conflicts & wars will benefit no one: President Mamnoon Hussain and President of Indonesia Ir. President of Indonesia H. Joko Widodo have agreed to work together for peace in Afghanistan and said that peace in Afghanistan is necessary for the development and progress of the region. Both countries will work together in this regard 18 Nishan-i-Imtiaz (Military) to Commander On the occasion, the President said that Pakistan and Saudi Royal Saudi Naval Forces Vice Admiral Arabia are the closest friends and the depth of their relationship Fahad Bin Abdullah Al-Ghofaily is difficult to describe in words. 24 CPEC most important initiative of our Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan said that the China Pakistan generation: PM Abbasi Economic Corridor (CPEC) is the most important initiative of our generation. “This is perhaps the most important initiative of our generation and the most visible part of the Belt and Road Initiative,” he said while addressing the inauguration ceremony of the first-ever International Gwadar Expo. -

3 Who Is Who and What Is What

3 e who is who and what is what Ever Success - General Knowledge 4 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success Revised and Updated GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Who is who? What is what? CSS, PCS, PMS, FPSC, ISSB Police, Banks, Wapda, Entry Tests and for all Competitive Exames and Interviews World Pakistan Science English Computer Geography Islamic Studies Subjectives + Objectives etc. Abbreviations Current Affair Sports + Games Ever Success - General Knowledge 5 Saad Book Bank, Lahore © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced In any form, by photostate, electronic or mechanical, or any other means without the written permission of author and publisher. Composed By Muhammad Tahsin Ever Success - General Knowledge 6 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Dedicated To ME Ever Success - General Knowledge 7 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success - General Knowledge 8 Saad Book Bank, Lahore P R E F A C E I offer my services for designing this strategy of success. The material is evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which are important for all competitive exams and interviews. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you found any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book. -

April 2018 Volume 09 Issue 04 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & Will Be Soon from UAE ”

April 2018 Volume 09 Issue 04 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE ” 10 22 30 34 10 President of Sri Lanka to play his role for His Excellency Maithripala Sirisena, President of the early convening of the SAARC Summit in Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka visited Pakistan Islamabad on the occasion of Pakistan Day. He was the guest of honour at the Pakistan Day parade on 23rd March 2018. 22 Economic Cooperation between Russia & On May 1, 2018 Russia and Pakistan are celebrating the 70th Pakistan Achievements and Challenges anniversary of establishing bilateral diplomatic relations. Our countries are bound by strong ties of friendship based on mutual respect and partnership, desire for multi-faceted and equal cooperation. 30 Peace with India is possible only after Pakistan has eliminated sanctuaries of all terrorists groups Resolving Kashmir issue: DG ISPR including the Haqqani Network from its soil through a wellthought- out military campaign, said a top military official. 34 Pakistanis a land of Progress & While Pakistan is exploring and expediting various avenues of Opportunities… development growth, it has been receiving consistent support from United Nations. 42 78th Pakistan Resolution Day Celebrated 42 The National Day of Pakistan is celebrated every year on the 23rd March to commemorate the outstanding achievement of the Muslims of Sub-Continent who passed the historic “Pakistan Resolution” on this day at Lahore in 1940 which culminated in creation of Pakistan after 7 years. 06 Diplomatic Focus April 2018 RBI Mediaminds Contents Group of Publications Electronic & Print Media Production House 09 New Envoys Presented Credentials to President Mamnoon Hussain Group Chairman/CEO: Mian Fazal Elahi 10 President of Sri Lanka to play his role for early convening of the SAARC Chief Editor: Mian Akhtar Hussain Summit in Islamabad Patron in Chief: Mr. -

Players Handicap

Karachi Golf Club W.E.F 17,September 2021 LIST OF HANDICAP W E F 12 January 2021. EXACT Play. S.no Mno N a m e H / C H / C 1 26 MR.ASGHAR D. HABIB 11.1 11 2 29 MRS. MAJIDA MOHSIN HABIB 34.0 34 3 32 MRS. ZUBAIDA HYDER HABIB 16.0 16 4 37 MRS. NISHAT KHAN 18.1 18 5 39 MR.NISSAR DOSSA 23.0 23 6 63 MR. KHAWAJA SAEED HAI 19.8 20 7 65 DR. M. S. HABIB 18.0 18 8 75 MR.MURTAZA QASIM 10.1 10 9 93 MR. AMINALI CURRIMBHOY 8.4 8 10 94 MR.SANAULLAH QURESHI 20.2 20 11 95 MR. MAHBOOB G. RAWJEE 21.5 22 12 105 MR.MAHMUD AHMAD 13.1 13 13 113 MR.VAZIR H.QURESHI 19.2 19 14 117 MR. ABBAS D. HABIB 13.9 14 15 119 MR. MUSLIM R. HABIB 16.3 16 16 120 MRS. PERVEEN MOHAMMAD 18.3 18 17 126 MR.KHALID RAFI 17.3 17 18 133 MR.HAMEEDULLAH KHAN 16.0 16 19 139 MR.HUSSAIN S. HAROON 12.6 13 20 145 MR. ASLAM R. KHAN 8.9 9 21 156 MR.MOHAMMAD BASHEER 18.0 18 22 159 MR. ADIL AHMED 17.0 17 23 162 MR. RAFIQUE DAWOOD 20.0 20 24 166 MR.ZAHID BASHEER 19.0 19 25 169 MRS. NAHEED MIRZA 18.0 18 26 172 MR. MOHAMMAD NASEER 21.8 22 27 174 MR. SALIM ADAYA 18.2 18 28 180 CAPT.MAHFOOZ ALAM (PIA) 14.4 14 29 184 MRS. -

NUSTNEWS Volume III / Issue VI

National University of Sciences & Technology DECEMBER 2012 MONTHLY NUSTNEWS Volume III / Issue VI Web Portal Launch Page 03 Allama Iqbal Photo- 24th PNEC Truck Art Workshop Essay Competition Convocation Page 19 Page 06 Page 12 Soft copy can be downloaded from NUST website: www.nust.edu.pk/downloads NUSTNEWS NUSTNEWS NUSTNEWS NUSTNEWS NUSTNEWS NUSTNEWS NUSTNEWS NUSTNEWS NUSTNEWS NUSTNEWS CONTENTS 3-11 HIGHLIGHTS 12-22 UPDATES FROM SCHOOLS 23-27 CO-CURRICULARS CORNER 28-29 SPORTS 30-31 ACHIEVEMENTS Editorial Team Editor: Maryam Khalid Assistant Editor: Faheem Khaliqdad Graphics & Layout: Kareem Muhammad Photography: Ghulam Rasool NUSTNEWS is a monthly publication, produced by Student Affairs Directorate, covering various events across the entire Student Reporters: University. It will be appreciated if the focal Zaid Bin Khamis Butt, Anum Yousaf Khan, persons send reports right after the event so Taimoor Ahmad as to give them timely coverage. 01 Highlights NUST web portal unveiled National University of Sciences and Technology unveiled its through the web portal would allow the visitors to appreciate world class web portal on Dec 17. In this connection, an impres- and understand NUST’s international standing with respect to sive ceremony was held at the main campus of the university. its academic programs and research. The Rector maintained Rector NUST graced the occasion as chief guest and inaugu- that the web portal would enhance web presence of NUST so rated the web portal. A number of dignitaries including former that to project its astounding stature and attract new students Governor Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Owais Ghani were also present and research scholars from across Pakistan as well as the world at the launch. -

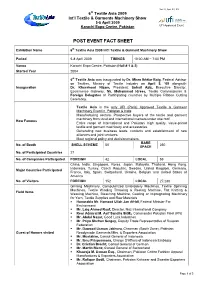

Post Event Fact Sheet

Ver: 0, Apr. 23, 09 6th Textile Asia 2009 Int’l Textile & Garments Machinery Show 5-8 April 2009 Karachi Expo Centre, Pakistan UFI Approved Event POST EVENT FACT SHEET Exhibition Name 6th Textile Asia 2009 Int’l Textile & Garment Machinery Show Period 5-8 April 2009 TIMINGS 10:00 AM ~ 7:00 PM Venue Karachi Expo Centre, Pakistan (Hall # 1 & 2) Started Year 2004 6th Textile Asia was inaugurated by Dr. Mirza Ikhtiar Baig, Federal Advisor on Textiles, Ministry of Textile Industry on April 5, ‘09 alongwith Inauguration Dr. Khursheed Nizam, President; Sohail Aziz, Executive Director, Ecommerce Gateway, Mr. Mohammad Idrees, Textile Commissioner & Foreign Delegates of Participating countries by Multiple Ribbon Cutting Ceremony. · Textile Asia is the only UFI (Paris) Approved Textile & Garment Machinery Event in Pakistan & India · Manufacturing sectors- Prospective buyers of the textile and garment machinery from local and international markets under one roof. How Famous · Entire range of International and Pakistani high quality, value-priced textile and garment machinery and accessories. · Generating new business leads, contacts and establishment of new alliances and joint ventures. · Meet regional policy and decision makers. BARE No. of Booth SHELL SCHEME 50 250 SPACE No. of Participated Countries 27 No. of Companies Participated FOREIGN 42 LOCAL 59 China, India, Singapore, Korea, Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Turkey, Czech Republic, Sweden, United Kingdom, Germany, Major Countries Participated France, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Ukraine, Belgium and United States of America No. of Visitors FOREIGN 152 LOCAL 27,280 Ginning Machinery, Computerized Embroidery Machines, Textile Spinning Machines, Textile Winding Throwing & Reeling Machine, Flat Knitting & Field Items Weaving Machine, Bleaching Machine, Coating or Impregnating Machinery for Yarn, Textile Supplies and Raw Materials § Honorable Mr. -

Kolkata Port Trust to Impose Royalty on Cargo Handlers

DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2012 365 29-12-2012 ; SIEM EMERALD at Vitoria (Brazil) PHOTO:Capt@ Jan Plug (c) Due to circumstances this week the newsclippings may reach you irregularly Distribution : daily to 24200+ active addresses 00-00-2012 Page 1 DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2012 365 31-`12-2012 JEPPENSEN MAERSK Departing Port Chalmers. photo: Renee van Baalen (c) Distribution : daily to 24200+ active addresses 00-00-2012 Page 2 DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2012 365 THe DEVON STRAIT passing the river Seine enroute LE HAVRE – Photo; Fabian Montreuil© Russian nuclear- powered icebreaker to head for the White Sea on Jan. 4, 2013 The nuclear-powered icebreaker "50 Years of Victory" is scheduled to depart from its home port of Murmansk on January 4, 2012, the ship owner Atomflot said. The vessel will set sail to the White Sea, where the powerful icebreaker will be engaged in escort of large-tonnage tankers from the edge of the White Sea to the inner anchorage of the port of Vitino. According to tentative schedule on January 16 the Atomflot- owened nuclear-powered icebreaker "Russia" will start her icebreaking and escort duties under the contract with Federal Rosmorport in the Gulf of Finland. The Russia will assist cargo Distribution : daily to 24200+ active addresses 00-00-2012 Page 3 DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2012 365 ships bound for the ports of Ust-Luga, Vysotsk, Primorsk and Big Port St. Petersburg. Photo50 Years of Victory : Beau Bisso (c) "All States, along the territorial waters border of which the nuclear-powered icebreaker will follow, have been noticed about its operation on the dates through the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. -

Pakistan from 1947………………………………………………… 4

(1) (2) IN THE NAME OF ALLAH THE MOST BENEFICENT AND MERCIFUL GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOK (A self study reference and practice electronic book for learners) M. FREE Books LATEST EDITION Designed and Compiled by: Niamat ullah zaheer S E E O N D E D I T I O N 2018 All Rights Reserved by the Publishers. Not Alowed to sell or print it or again publish. M A N S O O R S U C C E S S S E R I E S (3) P R E F A C E I voluntarily offer my services for designing this strategy of success. ― Mansoor Success Series General Knowledge 2018 ‖ is material evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources, since last few months. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which important for competitive exams. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you find any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book. Please Share This Book This book is free, but can I ask you to help me with one thing? Please post a link of the book on Facebook, Telegram Twitter and What‘s app to share it with your friends and classmates. -

Genral Quiz Booklet

1 2 Group 3 1st, 2nd year, SC to A-level Contents of Group 3 Part –I Pakistan Introduction 3 History- Pakistan Movement 3 Basic Facts 4 First, Largest And Longest 5 Administrative Divisions - Provinces 6 Heads Of State 8 Presidents and prime ministers 8 Chief martial law administrators 9 Comparative ranks in three services 9 Chief of armed forces 9 Highest Peaks 10 Rivers, Lakes and Passes 10 PART – II World Geographic Information Water bodies 11 Important Geographical Locations 13 Important Places of the World 15 World Summary 16 Principal Lakes of the World 18 World Land Locked Nations 18 Famous International Lines 18 Biggest, Highest, Largest and Longest in the World 19 PART – III Important World Organizations United Nations (UN) 20 NAM,EU, NATO, ECO, SAARC, 21 ASEAN, CW, G-8, Arab League, WTO, IMF, OPEC 22 PART – IV History of the World Muslim Dynasties 23 Famous Dynasties 24 Important Events in World History 25 World Wars 25 Wonders of the World 27 PART – V Great Personalities 28 Questions 32 PART – VI Islamiyat History and importance of Holy Quran 38 Information on Islam 39 Important dates in Pious Caliphate 40 Questions PART – VII Urdu Literature 47 Summary 48 Nazm 48 Ghazal 48 Questions PART - VIII English Literature 55 William Shakespeare 57 Hamlet 60 Julius Caesar 64 Questions PART - IX Every Day Science Physics 72 Chemistry 79 Biology 82 Mathematics 88 3 Army Burn Hall College for Boys Abbottabad General Quiz Competition Modern age is the age of knowledge and information. It is the knowledge in the domains of science and technology, due to which nations advance and dominate the world. -

Report – Book Launch “Gwadar: Balance in Transition”

INSTITUTE OF web: www.issi.org.pk phone: +92-920-4423, 24 STRATEGIC STUDIES |fax: +92-920-4658 Report – Book Launch “Gwadar: Balance in Transition” March 13, 2018 Written by: Ali Haider Saleem & Neelum Nigar Edited by: Najam Rafique 1|P a g e Report-Book Launch “Gwadar: Balance in Transition” March 13, 2018 Pictures of the Event P a g e | 2 Report-Book Launch “Gwadar: Balance in Transition” March 13, 2018 The China-Pakistan Study Centre (CPSC) at Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad (ISSI) launched a book titled “Gwadar: Balance in Transition” authored by Dr. Azhar Ahmad, Head of Department, Humanities and Social Sciences, Bahria University, on March 13, 2018. Former Chief of Naval Staff, Admiral Asif Sandila, was the Chief Guest at the occasion. The book is an in-depth study of the multi-dimensional aspects of Gwadar and contextualizes the evolving dynamics of the maritime affairs in the region. The distinguished commentators at the book launch included: Rear Admiral Farrokh Ahmed HI (M), Deputy Chief of Naval Staff (Projects), Naval Headquarters, Islamabad; Dr. Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema, Dean, Faculty of Contemporary Studies, National Defense University (NDU), Islamabad; Mr. Zhao Lijian, Deputy Chief of Mission at the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Islamabad; Welcoming the guests, the Chairman ISSI, Ambassador Khalid Mahmood lauded the scholarly efforts made by Dr. Azhar Ahmad in contributing to the existing literature on Pakistan’s maritime sector, especially the neglected importance of Gwadar. Dwelling on the history of the port, Ambassador Khalid Mahmood said that Pakistan purchased Gwadar from the Sultanate of Oman in 1958 and first phase of the port was completed by China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) by the end of 2005. -

Major Powers' Interests in Indian Ocean: Challenges And

Press Release International Conference “Major Powers’ Interests in Indian Ocean: Challenges and Options for Pakistan” First Day Pakistan cannot Remain Oblivious to Indian Ocean Admiral ( R ) Noman Bashir Former Chief of Naval Staff ( CNS) Pakistan Navy who was the chief guest at the two-day international conference on “Major Powers‟ Interests in Indian Ocean: Challenges and Options for Pakistan” that opened here on Tuesday, November 18th, 2014 organised by Islamabad Policy Research Institute in collaboration with Hans Seidel Foundation. He also said that continental mindset in Pakistan had distracted it from paying due attention to the developments in Indian Ocean. He said that Pakistan could not remain oblivious to developments taking place in the Indian Ocean as it directly impinged on its security and prosperity. He highlighted that Pakistan was heavily dependent on Indian Ocean with 95 per cent of its trade through sea, 100 per cent of its POL supplies were also through the Arabian Sea. Also, it had a reservoir of marine economic resources in its EEZ. He also said that the Indian strategists had propounded dominance of Indian Ocean and they argued that colonization of the subcontinent through East India Company was due to its weakness at sea. Admiral also highlighted the challenges like terrorism, piracy and armed robbery, drug and narco-trade, human trafficking and transportation of illegal migrants, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and marine pollution in Indian Ocean. He was of the opinion that the only way to ensure the „freedom of navigation‟ on its highways and equitable use of resources and counter future challenges was through a „cooperative approach‟. -

For the Cyber and Specialist "Intelligence" Industry in a Unique and Refreshing Approach to Service Provision

29 June – 5 July 2013 (Vol. 2; No.27/13) This Week's Newsletter is kindly Sponsored by: For the cyber and specialist "Intelligence" industry in a unique and refreshing approach to service provision Sponsor the newsletters - Click Ask us how you can be a sponsor of this newsletter in 2013 - click here. Feedback on the newsletter is welcomed too. Key message of cooperation and collaboration; oil theft, disasters at sea and IUU Fishing are main concerns– As piracy takes a yearly backseat, eyes turn to disasters at sea, the cause and effect of piracy relating to the matters affecting governments on land, but also the scramble for influence in piracy regions. Experts and commentators reiterate the need for information sharing and cooperation but how it can be all-inclusive remains the core issue for many. Kismayo infighting, internal wrangling in the Somali Federal Government and the “khaki envelope” demonstrates the difficulty in monitoring capacity building and is reflected in West Africa as near-replication of approach to piracy begins. Regulation of arms continues to hinder progress of maritime security despite focus on standards and responsibilities of the Master and PSCs. Oil theft, pipeline vandalism and illegal bunkering in Nigeria at a sufficiently worrisome level, MD for Shell Nigeria blames well-financed and highly organised criminals for running a parallel industry with $6 billion revenue lost annually; increasing cases, however, mean that the Nigerian Navy may not be able to contain the scourge. Bribery and corruption in W Africa ports challenge security along with piracy. Gambia rejects an agreement with the US on cooperation due to unequal partnership, which is likely to be repeated for West African states’ joint cooperation.