Frontispiece for Volume 2 March 1954

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copped Hall Character Appraisal Draft Final

Copped Hall Conservation Area Character Appraisal – Consultation Draft January 2011 Copped Hall Conservation Area Character Appraisal & Management Plan Consultation Draft January 2011 Epping Forest District Council – Directorate of Planning and Economic Development 1 Copped Hall Conservation Area Character Appraisal – Consultation Draft January 2011 Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 Definition and purpose of character appraisals………………………………...…………..4 Scope and nature of character appraisals…………………………………………………..4 Extent of the conservation area……………………………..………………..……………...4 Methodology……………………….…………………………………………..…..…………..4 2. Planning Policy Context……………………………………………….………………..…..5 Local Plan policies……………………………………………………………………………..5 3. Summary of Special Interest……………………………………………………………….6 Definition of special architectural and historic interest………………………….…………6 Definition of the character of Copped Hall Conservation Area……………….…………..6 4. Location and Population………………………………….............................………... ….7 5. Topography and Setting…………………………………………………………………….8 6. Historical Development and Archaeology……………………………………………...10 Origins and development…………………………………………………………..………..10 Archaeology…………………………………………………………………………………..14 7. Character Analysis………………………………………………………………………….18 General character and layout…………………………………………………………........18 Key views……………………………………………………………..…………….…………20 Character Areas…………………………………………………………...…………………21 Buildings of architectural and historic interest…………………….………………………28 Traditional -

POWER RELATIONS in the ROYAL FORESTS of ENGLAND Patronage, Privilege and Legitimacy in the Reigns of Henry III and Edward I

POWER RELATIONS IN THE ROYAL FORESTS OF ENGLAND Patronage, privilege and legitimacy in the reigns of Henry III and Edward I University of Oulu Department of History Master’s Thesis November 2013 Andrew Pattison TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 1 Roles – The royal forests and the structures of power in England 13 2 Abuse – Peter de Neville, forester of Rutland Forest 23 3 Contestation – Walter de Kent, forester of New Forest 44 Conclusion – The diffuse nature of power in 13th-century England 64 Sources and bibliography of works consulted 72 1 INTRODUCTION In this study I shall examine the subject of power relations in the royal forests of England. The vast forests of late-medieval England contained a variety of valuable resources; some were mundane, like timber and land, and some were of a more symbolic nature like deer and the right to hunt. Control and usage of these resources was to a great extent dictated by the unique legal codes of the forests which aimed to maintain the forests to the king’s benefit. But at the same time, forests, by their innate nature, were difficult to guard and thus invited misappropriation. This thorny conundrum caused a great deal of friction amongst the inhabitants of the forest (the primary users) and the royal foresters charged with overseeing resource usage in the forest. This general discord over access to resources will serve as the point of departure for the present study. In my analysis of resource use in the forest I shall attempt to analyze the interplay of power between the various actors in the forest, namely, the local inhabitants and the foresters. -

Epping Forest Consultative Committee

Public Document Pack Epping Forest Consultative Committee Date: WEDNESDAY, 10 FEBRUARY 2021 Time: 7.00 pm Venue: PUBLIC MEETING (ACCESSIBLE REMOTELY) Members: Graeme Doshi-Smith (Chairman) Benjamin Murphy (Deputy Chairman) Sylvia Moys Caroline Haines Judith Adams, Epping Forest Heritage Trust Gill James, Friends Of Wanstead Parklands Martin Boyle, Theydon Bois & District Rural Preservation Society Jill Carter, Highams Residents Association Susan Creevy, Loughton Residents Association Matthew Frith, London Wildlife Trust Robert Levene, Bedford House Community Association Tim Harris, Wren Wildlife & Conservation Group Ruth Holmes, London Parks & Gardens Trust Andy Irvine, Bushwood Area Residents Association Brian Mcghie, Epping Forest Conservation Volunteers Deborah Morris, Epping Forest Forum Gordon Turpin, Highams Park Planning Group (Inc Snedders) Mark Squire, Open Spaces Society Tim Wright, Orion Harriers Carol Pummell, Epping Forest Riders Association Steve Williamson, Royal Epping Forest Golf Club Verderer Michael Chapman Dl Verderer Paul Morris Verderer Nicholas Munday Verderer H.H William Kennedy Enquiries: Richard Holt [email protected] Accessing the virtual public meeting Members of the public can observe the virtual public meeting at the below link: https://youtu.be/cN6iy3beOFs This meeting will be a virtual meeting and therefore will not take place in a physical location following regulations made under Section 78 of the Coronavirus Act 2020. A recording of the public meeting will be available via the above link following the end of the public meeting for up to one municipal year. Please note: Online meeting recordings do not constitute the formal minutes of the meeting; minutes are written and are available on the City of London Corporation’s website. -

Epping Forest

Cultural Learning Resources OUR ENVIRONMENT E P P I N G SHEETS FACT F O R E S T Print-friendly PDF E P P I N G F O R E S T Epping Forest is a 5,900-acre area of ancient woodland between Epping in Essex to the north, and Forest Gate to the south. It is the largest public open SHEETS FACT space in the London area. It is a former royal forest, and is managed by the City of London Corporation. CONTENTS EPPING FOREST MAP 03 A BRIEF HISTORY OF EPPING FOREST 04 WILLIAM MORRIS AND EPPING FOREST 08 CHINGFORD PLAIN 09 OUR ENVIRONMENT: EPPING FOREST 02 E P P I N G F O R E S T Copped Hall Park Warlies Waltham Park Abbey Epping Gi ord Wood The Warren Plantation Epping Thicks Ambresbury Banks Theydon Bois Jacks Big View Hill Theydon Bois Deer SHEETS FACT Sanctuary Theydon Wake Green Valley Furze Pond Ground Great Monk Wood Debden Green Epping Forest Visitor Centre Little Monk Wood Baldwins Hill High Truelove’s Loughton Beach Camp Robin Hood Roundabout Femhills Staples Hill Loughton Bury The Debden Wood Stubbles Yardley Sewardstonebury Hill The Warren Loughton Connaught Warren Water Hill Chingford Golf Course Pole Queen Elizabeth Hill Hunting Lodge North Farm Chingford Whitehall Plain Chigwell Buckhurst Hill Chingford Lord’s Bushes Knighton Wood Chigwell Roding Valley Woodford Green Highams Park Woodford E P P I N G F O R E S T A Brief History of Epping Forest Early History There has been continuous tree cover in Epping Forest for well over 3,000 years, and signs of human occupation since the Iron Age. -

The Forest Eyre, 1154-1368

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The forest eyre, 1154-1368. Winters, Jane Frances The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 The Forest Eyre, 1154-1368 Ph.D. Jane F. Winters King's College London (LONDOn) Abstract The main body of this thesis consists of a catalogue and description of the documentation of the forest eyre between 1154 and 1368. -

Gloucester and the Forest of Dean

m iT in ix e r & a m a r UnCover The CoTswolDs v Y a a il o T a p C b T h l io e n The ForesT s oF Dean Gloucester Cathedral Puzzlewood M a p From the cultural and © C o t s w historic Gloucester o l d s T o u Docks and city centre, r i s its museums, arts, and m Cathedral, travel out into the Forest of Dean to explore on foot, I m by bike or by vehicle. a g e s © D Visit a magnificent castle, a v i d follow twisting biking tracks, B r o a d take a brewery tour, climb to b e n t , the trees, explore the caves, A n g e l or walk an art trail through the o H o r woods. Beginning in Gloucester n a k , and finishing near Ross-on- D u n c a Wye, this tour can be done in n P o w any order and requires transport e l by vehicle between many l destinations. For the active and the adventurous – families, groups, friends and couples. Gloucester Get adventurous with Canoeing on Foxtail Cathedral an outdoor activity the river wye Distillery DaY 1 DaY 2 DaY 3 Three Choirs vineyard Clearwell Caves Tintern abbey GloUCesTer ForesT oF Dean wYe valleY www.cotswolds.com From midday the café serves light bites which includes delicious hot and cold sandwiches, fish and chips, smoked platters, cakes, puddings and cream teas. The restaurant offers an extended menu and is open for lunch Monday to Sunday and dinner Thursday to Saturday. -

Forestry Commission Bulletin: Alternative Silvicultural Systems to Clear Cutting in Britain: a Review

Forestry Commission Bulletin 115 in Britain: A Review Cyril Hart Forestry Commission ARCHIVE FORESTRY COMMISSION BULLETIN 115 Alternative Silvicultural Systems to Clear Cutting in Britain: A Review Cyril Hart LONDON : HMSO © Crown copyright 1995 Applications for reproduction should be made to HMSO Copyright Unit, Duke Street, Norwich NR3 1PD ISBN 0 11 710334 9 Hart, C.; 1995. Alternative Silvicultural Systems to Clear Cutting in Britain: A Review. Bulletin 115, HMSO, London, xiv + 101pp. FDC 22: 221.1: (410): (4) KEYWORDS: Amenity, Broadleaves, Conifers, Conservation, Establishment, Forestry, Management Cyril Hart Dr Cyril Hart OBE is a Chartered Surveyor and Chartered Forester and is the Queen’s Senior Verderer for the Forest of Dean. He is author of several books on Britain’s forests and trees of which the best known is his authoritative Practical forestry for the agent and surveyor. Professor Julian Evans and Mr Gary Kerr of the Forestry Commission’s Research Division contributed to this important review through editorial involvement and text revision. Front cover: Weasenham New Wood, Please address enquiries Norfolk: mixed conifer selection system; about this publication to: in the picture, Major Richard Coke Research Publications Officer DSO MC, the present owner. The Forestry Commission (P e t e r G o o d w i n ) Research Division Alice Holt Lodge, Wrecclesham Back cover: Dr Cyril Hart OBE Farnham, Surrey GU10 4LH (D a v id G r e e n ) Acknowledgements This Bulletin was written with the benefit of Professor J.D. Matthews’s updat ing (1989) of Professor R.S. Troup’s two editions of Silvicultural systems (1928, 1952), the latter edition by Dr E.W. -

The Charter of the Forest: Evolving Human Rights in Nature

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2014 The Charter of the Forest: Evolving Human Rights in Nature Nicholas A. Robinson Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Environmental Law Commons, Legal History Commons, Natural Law Commons, and the Natural Resources Law Commons Recommended Citation Nicholas A. Robinson, The Charter of the Forest: Evolving Human Rights in Nature, in Magna Carta and the Rule of Law 311 (Daniel Barstow Magraw et al., eds. 2014), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/ lawfaculty/990/. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 12 The Charter of the Forest: Evolving Human Rights in Nature Nicholas A. Robinson Ln 1759 William Bla kstone published TJ)e Great Charter and the harter of tbe Forest, with other Authentic Instruments, to whjch is Prefixed An lntrodu tory Discourse containing The History of the hal·ters.! Since then, much ha been written about Magna Carta but little has been written about the companioD Forest Charter. This chapter reexamines "the e twO sacred charters,,,2 focusing u,p n the "liberties of the for sr '3 that the po,re t barter established, an I how they evolved amjd the contentious struggles over stewardship of England' fore t re urce.4 The Forest harter both contributed to establishing the ruJe of law and aJ 0 laun hed ight enturies f legislation conserving forest resources and lands ape. -

Trust in the Forest

EPPING FORES T HERIT AGE TRUS T TRUST IN THE FOREST JULY ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2019 IN THIS ISSUE... 5 Years On 1 Dear Member 2 The Next Verderers Election 2 The Parish Reeve 3 Epping Forest Consultative Committee Meeting 4 © Gill Woods Photography Walk Reports 6 Green Infrastructure 8 FIVE YEARS ON - A CELEBRATION Volunteering in the Trust 9 Social Media 9 On April 5, 2014, the Friends of Epping Forest (now Epping Forest Heritage Trust) took on the operation of the Epping Forest Visitor Centre at High Beach due to threat of closure. Since then, more than 96,000 Children’s Activities 10 visitors (both local and international) have come to the Centre, seeking guidance on where to go, what ‘New’ Forest Leaflet 10 to do, and to discover more about our very special Epping Forest. Advance Notice AGM 10 On April 5, 2019, we were very pleased to be joined by local dignitaries including Dame Eleanor Laing Waltham Forest London MP, the Mayors of Epping, Loughton and Waltham Abbey and the Chairman of Epping Forest District Borough of Culture 10 Council along with the Chairman of the EF and Commons Committee, the Verderers, Committee members Hot off The Press... 10 and Staff of the City of London. A splendid opportunity for them to help us celebrate our achievements at Dates For Your Diary 11 the Centre and to look forward to the next five years and more! Annual Epping Forest The volunteer team have done a magnificent job. Operating as a gateway to the Forest from Thursday to Celebration Walk 12 Sundays and Bank Holidays (over 1,000 days), we have supported 96,500 visitors through our Join Us! 12 volunteer effort totalling 15,081 hours! Circa 20% of our visitors are first time visitors. -

Creativity Challenge Quiz Answers

2020 Creativity Challenge Quiz Answers We hope you have been enjoying the activities in the Creativity Challenge over the past weeks. Have you had a chance to have a go at the quiz too? This can help you find out more about the amazing history of the district, and about some of our great partners in Epping Forest Creative Network. Now it is time to find out if you got the right answers … 1. Which Anglo Saxon King is thought to be buried at the Abbey Church, Waltham Abbey? A. King Harold II. While the Abbey of Waltham was certainly a very important place for Harold, we can’t be 100% sure he is buried there. There are other places that lay claim to be his final resting place. Some think there wouldn’t have been much of him left to bury after the Battle of Hastings. Either way, it is still very important to commemorate Harold’s connection to Waltham Abbey. 2. Which popular festival takes place at St John’s Church, Epping each Christmas? A. It is of course the Christmas Tree Festival. Lots of community groups and local business decorate trees each year as part of the town’s Christmas festivities. St John’s Church as well as many other churches across the district welcome all sorts of different community events and activities. Our churches are very special places to visit, with wonderful stories to explore too. 3. Near which town in the district can you find the oldest wooden church in the world? A. Churches don’t get much more special that St Andrew’s juxta Ongar in Greensted – a long name for a wonderful small church, and one that is a real treasure of the district. -

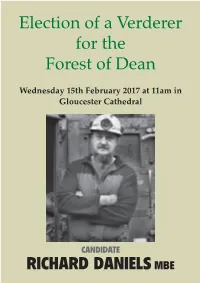

Election of a Verderer for the Forest of Dean RICHARD DANIELSMBE

Election of a Verderer for the Forest of Dean Wednesday 15th February 2017 at 11am in Gloucester Cathedral CANDIDATE RICHARD DANIELS MBE What is a Who can vote? The election of a verderer follows Verderer? medieval custom: a show of hands by the freeholders of Gloucestershire attending There are four a hearing arranged by the High Sheriff. Verderers, an order People living in Gloucester City cannot that traces its vote as they are covered by a different origins to Norman royal charter. times. They meet in the Verderers Court in Use your vote Speech House. You can only vote in person They were established to administer Forest Wednesday 15th February 11am Law, introduced to Gloucester Cathedral provide for beasts of the forest, in Voters must arrive with ample time to be particular deer and able to register to vote before the hearing boar, and for the begins at 11am. To be eligible to vote you protection of their must own freehold land or property in the habitat. County, except the city of Gloucester. The earliest allusion to Verderers in Dean is in 1216; the earliest named are those in 1221. The Verderers play a vital role in the protection of the Forest. Click here for Verderers web site Speech House - where the Verderers sit RICHARD DANIELS Rich Daniels was born at the Dilke Memorial Hospital in Cinderford. He has lived in the Forest all his life despite having travelled widely in the UK and abroad. Rich has a deep love for the Dean and an understanding of the complexities of the Forest. -

Epping Forest

li|pF](KC5jFbR£ST Vufi f^ap >rnia f\j^ EPPING FOREST EPPING FOREST BY EDWARD NORTH BUXTON VERDERER LONDON: EDWARD STANFORD, 55, CHARING CROSS, S.W, 1885 Printed by Edward Stanford, Jj, Charing Cross, Lcntdon, S.l-f. PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION. The idea of writing a Guide to the Forest oc- curred to me when I observed how small a percentage of our summer visitors ever venture far from the point at which they are set down by train or vehicle. This is hardly a desirable state of things; and as steam merry-go-rounds and "five shies for a penny" can be enjoyed with equal facility in London, it seems a pity not to encourage, as far as lies in one's power, a more enterprising spirit. It appears that this reluctance to enter the thicket springs, not from indifference to the attractions of the Forest, but solely from a dread, not unnatural to those unaccustomed to the country, of losing the way ; and I hope that clear directions how to find, and follow, the most beautiful and in- teresting routes, will be appreciated. I trust I am not egotistical in thinking that, as I have lived all my life in one or other of the Forest parishes, and for many years have been in the constant habit of exploring its inner recesses, the public cannot have a better adviser than myself in this matter. I am aware that some excellent cheap Guide- 2091012 vi PREFACE. books to the Forest have been published ; but they do not enter with sufficient minuteness into topographical details to serve as a handbook to the stranger who desires to penetrate the wilder parts of the wood.