Singapore |17 October 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Reverberations from Regime Shake-Up in Rangoon.Qxd

Asia-PacificAsia-Pacific SecuritySecurity SStudiestudies RegionalRegional ReverberationsReverberations fromfrom RegimeRegime Shake-upShake-up inin RangoonRangoon Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies Volume 4 - Number 1, January 2005 Key Findings The reverberations from the recent regime shake-up in Rangoon continue to be felt in regional capitals. Since prime minister Khin Nyunt was the chief architect of closer China-Burma strategic ties, his sudden removal has been interpret- ed as a major setback for China's strategic goals in Burma. Dr. Mohan Malik is a Professor with the Asia-Pacific Center for However, an objective assessment of China's strategic and eco- Security Studies. nomic needs and Burma's predicament shows that Beijing is His work focuses main- unlikely to easily give up what it has already gained in and ly on Asian Geopolitics through Burma. From China's perspective, Burma should be and Proliferation in Asia-Pacific region. His satisfied to gain a powerful friend, a permanent member of the most recent APCSS UN Security Council, and an economic superpower that comes publication is “India-China Relations: bearing gifts of much needed military hardware, economic aid, Giants Stir, Cooperate infrastructure projects and diplomatic support. and Compete ” The fact remains that ASEAN, India and Japan cannot compete with China either in providing military assistance, diplomatic support or in offering trade and investment benefits. With the UN-brokered talks on political reconciliation having reached a dead end, it might be worthwhile to start afresh with a dia- logue framework of ASEAN+3 (ASEAN plus China, India and Japan) on Burma. This would also put to test China's oft-stated commitment to multi- lateralism and Beijing's penchant for "Asian solutions to Asian problems". -

DASHED HOPES the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS DASHED HOPES The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Background ..................................................................................................................... 6 II. Section 66(d) -

Participants List

Participants List (10 September 2019) Participating Name and Position title Position title Contact countries 1 Bangladesh Mr Sheikh Kaushik IQBAL Assistant Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs [email protected] 2 Bhutan Mr Tenzin TENZIN Desk Officer, Ministry of Foreign Affairs [email protected] 3 Indonesia Dr Gulardi NURBINTORO Foreign Service Officer, Directorate for Legal Affairs and [email protected] Territorial, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 4 Lao PDR Mr Singhalath BOUPHA Advisor, Department of International Organizations, [email protected] Ministry of Foreign Affairs 5 Myanmar Dr. Cherry AUNG Professor and Head, Department of Marine Science, TBC Pathein University 6 Dr. Zaw Htet AUNG Professor and Head, Department of Petroleum TBC Engineering, Yangon Technological University 1 Participating Name and Position title Position title Contact countries 7 Dr. Zaw Min AUNG Executive Geologist, Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, [email protected] Ministry of Electricity and Energy 8 Dr. Zaw Moe AUNG Lecturer, Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine TBC University 9 Dr. Mi Khin Saw AUNG Professor and Head, Department of Law, Dagon TBC University 10 Dr. Day Wa AUNG Professor and Head, Department of Geology, Yangon TBC University 11 Mr. Ngwe Zaw AUNG Deputy Director, Union Attorney General Office TBC 12 Dr. Cho Cho AYE Professor and Head, Department of Geology, East TBC Yangon University 13 Dr. Khin Chit CHIT Professor and Head, Department of Law, Yangon TBC University 14 H.E Dr. Myo Thein GYI Union Minister for the Ministry of Education TBC 15 Dr. Ko Ye HLA Professor, Department of Geology, Mawlamyine University TBC 16 Dr. -

From Kunming to Mandalay: the New “Burma Road”

AsieAsie VVisionsisions 2525 From Kunming to Mandalay: The New “Burma Road” Developments along the Sino-Myanmar border since 1988 Hélène Le Bail Abel Tournier March 2010 Centre Asie Ifri The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the authors alone. ISBN : 978-2-86592-675-6 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2010 IFRI IFRI-BRUXELLES 27 RUE DE LA PROCESSION RUE MARIE-THÉRÈSE, 21 75740 PARIS CEDEX 15 - FRANCE 1000 - BRUXELLES, BELGIQUE PH. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 PH. : +32 (2) 238 51 10 FAX: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 FAX: +32 (2) 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] WEBSITE: Ifri.org China Program, Centre Asie/Ifri The Ifri China Program’s objectives are: . To organize regular exchanges with Chinese elites and enhance mutual trust through the organization of 4 annual seminars in Paris or Brussels around Chinese participants. -

U.S. Restrictions on Relations with Burma

U.S. Restrictions on Relations with Burma Updated March 18, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44570 U.S. Restrictions on Relations with Burma Summary Major changes in Burma’s political situation since 2016 have raised questions among some Members of Congress concerning the appropriateness of U.S. policy toward Burma (Myanmar) in general, and the current restrictions on relations with Burma in particular. During the time Burma was under military rule (1962–2011), restrictions were placed on bilateral relations in an attempt to encourage the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, to permit the restoration of democracy. In November 2015, Burma held nationwide parliamentary elections from which Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) emerged as the party with an absolute majority in both chambers of Burma’s parliament. The new government subsequently appointed Aung San Suu Kyi to the newly created position of State Counselor, as well as Foreign Minister. While the NLD controls the parliament and the executive branch, the Tatmadaw continues to exercise significant power under provisions of Burma’s 2008 constitution, impeding potential progress towards the re-establishment of a democratically-elected civilian government in Burma. On October 7, 2016, after consultation with Aung San Suu Kyi, former President Obama revoked several executive orders pertaining to sanctions on Burma, and waived restrictions required by Section 5(b) of the Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE (Junta Anti-Democratic Efforts) Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-286), removing most of the economic restrictions on relations with Burma. On December 2, 2016, he issued Presidential Determination 2017-04, ending some restrictions on U.S. -

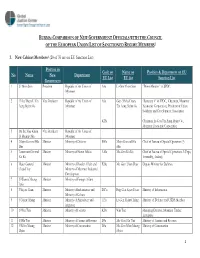

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

China in Burma

CHINA IN BURMA : THE I NCREASING I NVESTMENT OF CHINESE MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS IN BURMA’S HYDROPOWER, OIL AND NATURAL GAS, AND MINING SECTORS UPDATED: September 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EarthRights International would like to thank All Arakan Student & Youth Congress, Arakan Oil Watch, Burma Relief Center, Courier Research Associates, Images Asia E-Desk, Kachin Development Networking Group, Kachin Environmental Organization, Karen Rivers Watch, Karenni Development Research Group, Lahu National Developmen t Organization, Mon Youth Progressive Organization, Palaung Youth Network Group, Salween Watch Coalition, Shan Sapawa and Shwe Gas Movement, for providing invaluable research assistance and support for this report. Free reproduction rights with citation to the original. EarthRights International (ERI) is a non-government, non- profit organization that combines the power of the law and the power of people in defense of human rights and the environment, which we define as “earth rights.” We specialize in fact-finding, legal actions against perpetrators of earth rights abuses, training grassroots and community leaders, and advocacy campaigns. Through these strategies, ERI seeks to end earth rights abuses, to provide real solutions for real people, and t o promote and protect human rights and the environment in the communities where we work. Southeast Asia Office U.S. Office P.O. Box 123 1612 K Street NW, Suite 401 Chiang Mai University Washington, D.C. Chaing Mai, Thailand 20006 50202 Tel: 1-202-466-5188 Tel: 66-1-531-1256 Fax: 1-202-466-5189 -

LAST MONTH in BURMA MAY News from and About Burma 2007

LAST MONTH IN BURMA MAY News from and about Burma 2007 Pro-democracy campaigns intensify During May activists intensified pro-democracy campaigns with public demonstrations and activities throughout Burma. The regime responded with a crackdown on peaceful demonstrations. According to The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, (AAPPB), in May alone, the regime arrested 99 democracy and human rights activists. 3 of the activists were imprisoned, 24 were released, and 74 are still being detained. NLD members launched a ‘Release Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’ campaign on 1 May. The campaign, led by prominent activist and a NLD youth leader Su Su Nway, included a daily prayer campaign. However, Su Su Nway and around 30 other activists wearing ‘Free Aung San Suu Kyi’ T-shirts were arrested on 15 May as they headed to pagodas around Rangoon to pray for the release of Aung San Suu Kyi. Another 11 activists were arrested in Rangoon as they prepared to march to the Shwedagon Pagoda and the following day a further 15 pro-democracy activists were arrested in Rangoon. They were released after a few hours in detention. In other events, a 62-year-old woman activist was arrested after staging a solo protest for the release of Aung San Suu Kyi in front of Rangoon’s City Hall. Burma’s Military Affairs Security detained about 30 people who were planning to attend a May Day workshop at the American Center in Rangoon. The month of demonstrations concluded on 30 May as the NLD held ceremonies in Rangoon and Mandalay to mark the four-year anniversary of the Depayin massacre. -

Preparatory Survey on the Project for Improvement of Medical Equipment in Hospitals in Yangon and Mandalay in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar

REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR MINISTRY OF HEALTH PREPARATORY SURVEY ON THE PROJECT FOR IMPROVEMENT OF MEDICAL EQUIPMENT IN HOSPITALS IN YANGON AND MANDALAY IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR FEBRUARY, 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY INTERNATIONAL TOTAL ENGINEERING CORPORATION HDD JR 13-025 REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR MINISTRY OF HEALTH PREPARATORY SURVEY ON THE PROJECT FOR IMPROVEMENT OF MEDICAL EQUIPMENT IN HOSPITALS IN YANGON AND MANDALAY IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR FEBRUARY, 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY INTERNATIONAL TOTAL ENGINEERING CORPORATION PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the preparatory survey and entrust the survey to International Total Engineering Corporation. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, and conducted field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar for their close cooperation extended to the survey team. February, 2013 Nobuko KAYASHIMA Director General, Human Development Department Japan International Cooperation Agency Summary Summary (1) Outline of the Country The Republic of the Union of Myanmar (hereinafter referred to as “Myanmar”) is located in the Indochina Peninsula, accounting its land area of 676,578 ㎢, which equivalents to 1.8 times larger than Japan's total land area. -

Myanmar Politics & People in 2015

Myanmar Politics & People in 2015 Myanmar Politics & People in 2015 1. Background ..........................................................................................................................................3 2. Political Structure ................................................................................................................................4 3. Political System ....................................................................................................................................4 4. Issues ....................................................................................................................................................5 4.1. Peace ..........................................................................................................................................................................5 4.2. Economy ...................................................................................................................................................................6 4.3. Constitutional Amendment ...............................................................................................................................7 4.4. Land ............................................................................................................................................................................7 4.5. Sanctions ..................................................................................................................................................................7 -

Asymmetric Bargaining Between Myanmar and China in the Myitsone Dam Controversy: Social Opposition As David’S Stone Against Goliath Sze Wan Debby CHAN 1

Asymmetric Bargaining between Myanmar and China in the Myitsone Dam Controversy: Social Opposition as David’s Stone against Goliath Sze Wan Debby CHAN 1 In May 2011, the Sino-Myanmar relations was elevated to a ‘comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership’. Soon after that, the unilateral suspension the China-backed Myitsone Dam by President Thein Sein has redefined the bilateral ties. What made Myanmar renege on its commitment which could entail innumerable compensation? This research employs the two-level game theory in analysing the Myitsone Dam controversy. Based on dozens of interviews conducted in Myanmar, I argue that the halt of the project was not entirely a voluntary defection of the Myanmar government. Amid democratisation in the country, the ‘Save the Ayeyarwady’ campaign against the dam was able to galvanise nationwide support through a series of awareness raising activities in 2011. With the rise of audience cost in Myanmar, China gradually conceded that the quasi-civilian government could no longer ignore societal actors in relation to foreign investment projects. Since 2012, China has been actively engaging with the opposition and civil society organisations in Myanmar. China’s new diplomatic approach reflects the importance of social opposition in the international dispute. The Myitsone Dam case may have a wider application of using social opposition as bargaining resources in asymmetric international negotiations outside the China-Myanmar context. Introduction In face of the popular ‘Save the Ayeyarwady’ campaign against the construction of the China- backed Myitsone hydropower dam, then Myanmar’s 2 President Thein Sein suspended the project during his tenure on 30 September 2011. -

Human Rights Council the Economic Interests of the Myanmar Military

A/HRC/42/CRP.3 5 August 2019 English only Human Rights Council Forty-second session 9–27 September 2019 Agenda item 4 Human Rights situations that require the Council’s attention The economic interests of the Myanmar military Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar An earlier version of this repot, released on 5 August 2019, misindentified details related to a number of companies and individuals. They have been corrected in this version of the report, and are outlined in “Update from the UN Independent International Fact- Finding Mission on Myanmar on its report on “The economic interests of Myanmar’s military”, available on the Mission’s website at https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/MyanmarFFM/Pages/EconomicInterestsMyanmarMilitary.aspx GE. A/HRC/42/CRP.3 Contents Page I. Executive summary and key recommendations ............................................................................... 3 II. Mandate, methodology, international legal and policy framework .................................................. 6 A. Mandate ................................................................................................................................... 6 B. Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 7 C. International legal and policy framework ................................................................................ 8 III. Mapping Tatmadaw economic structures and interests ...................................................................