Chapter 3 Sedimentology and Stratigraphy of the Baynunah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Pharmaceutical Providers Within UAE for Daman's Health Insurance Plans

List of Pharmaceutical Providers within UAE for Daman ’s Health Insurance Plans (InsertDaman TitleProvider Here) Network - List of Pharmaceutical Providers within UAE for Daman’s Health Insurance Plans This document lists out the Pharmacies and Hospitals available in Daman’s Network, dispensing prescribed medicines, for Daman’s Health Insurance Plan (including Essential Benefits Plan, Classic, Care, Secure, Core, Select, Enhanced, Premier and CoGenio Plan) members. Daman also covers its members for other inpatient and outpatient services in its network of Health Service Providers (including hospitals, polyclinics, diagnostic centers, etc.). For more details on the other health service providers, please refer to the Provider Network Directory of your plan on our website www.damanhealth.ae or call us on the toll free number mentioned on your Daman Card. Edition: October 01, 2015 Exclusive 1 covers CoGenio, Premier, Premier DNE, Enhanced Platinum Plus, Select Platinum Plus, Enhanced Platinum, Select Platinum, Care Platinum DNE, Enhanced Gold Plus, Select Gold Plus, Enhanced Gold, Select Gold, Care Gold DNE Plans Comprehensive 2 covers Enhanced Silver Plus, Select Silver Plus, Enhanced Silver, Select Silver Plans Comprehensive 3 covers Enhanced Bronze, Select Bronze Plans Standard 2 covers Care Silver DNE Plan Standard 3 covers Care Bronze DNE Plan Essential 5 covers Core Silver, Secure Silver, Core Silver R, Secure Silver R, Core Bronze, Secure Bronze, Care Chrome DNE, Classic Chrome, Classic Bronze Plans 06 covers Classic Bronze -

Developing a Framework of Dune Accumulation in the Northern Rub Al

Developing a framework of Quaternary dune accumulation in the northern Rub’ al-Khali, Arabia. Andrew R Farranta, Geoff A T Dullerb, Adrian G Parkerc, Helen M Robertsb, Ash Partond, Robert W O Knoxa#, and Thomas Bidea. aBritish Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG, UK. [email protected] [corresponding author 0115 9363184]. bAberystwyth Luminescence Research Laboratory, Department of Geography & Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB, Wales, UK cDepartment of Social Sciences, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, OX3 0BP, UK dResearch Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, School of Archaeology, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX1 2HU, UK #Deceased Abstract Located at the crossroads between Africa and Eurasia, Arabia occupies a pivotal position for human migration and dispersal during the Late Pleistocene. Deducing the timing of humid and arid phases is critical to understanding when the Rub’ al-Khali desert acted as a barrier to human movement and settlement. Recent geological mapping in the northern part of the Rub’ al-Khali has enabled the Quaternary history of the region to be put into a regional stratigraphical framework. In addition to the active dunes, two significant palaeodune sequences have been identified. Dating of key sections has enabled a chronology of dune accretion and stabilisation to be determined. In addition, previously published optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dates have been put in their proper stratigraphical context, from which a record of Late Pleistocene dune activity can be constructed. The results indicate the record of dune activity in the northern Rub’ al-Khali is preservation limited and is synchronous with humid events driven by the incursion of the Indian Ocean monsoon. -

Geological Passport

Geological Passport www.moei.gov.ae Contact Details Ministry of Energy & Industry Geology & Mineral Resources Department PO Box 59 - Abu Dhabi United Arab Emirates Phone +971 2 6190000 Toll Free 8006634 Fax +971 2 6190001 Email: [email protected] Website: www.moei.gov.ae © Ministry of Energy & Industry, UAE Geological Setting of the UAE e United Arab Emirates (UAE) are located on the southern side of the Arabian Gulf, at the north-eastern edge of the Arabian Plate. Although large areas of the country are covered in Quaternary sediments. e bedrock geology is well exposed in the Hajar Mountains and the Musandam Peninsula of the eastern UAE, and along the southern side of the Arabian Gulf west of Abu Dhabi. e geology of the Emirates can be divided into ten main components: (1) e Late Cretaceous UAE-Oman ophiolite; (2) A Middle Permian to Upper Cretaceous carbonate platform sequence, exposed in the northern UAE (the Hajar Supergroup); (3) A deformed sequence of thin limestone’s and associated deepwater sediments, with volcanic rocks and mélanges, which occurs in the Dibba and Hatta Zones; Geological map of the UAE (Scale 1:500 000) 1 (4) A ploydeformed sequence of metamorphic rocks, seen in the Masafi – Ismah and Bani Hamid areas; (5) A younger, Late Cretaceous to Palaeogene cover sequence exposed in a foreland basin along the western edge of the Hajar Mountains; (6) An extensive suite of Quaternary fluvial gravels and coalesced alluvial fans extending out from the Hajar Mountains; (7) A sequence of Late Miocene sedimentary rocks exposed in the western Emirates; (8) A number of salt domes forming islands in the Arabian Gulf, characterised by complex dissolution breccias with a varied clast suite of mainly Neoproterozoic (Ediacaran) sedimentary and volcanic rocks; (9) A suite of Holocene marine and near-shore carbonate and evaporate deposits along the southern side of the Arabian Gulf forming the classic Abu Dhabi sabkhas and Extensive Quaternary to recent aeolian sand dunes which underlie the bulk of Abu Dhabi Emirate. -

Clinical Research in the United Arab Emirates

Market Report Clinical Research in the United Arab Emirates With a bustling population composed of a mixture of operating procedures (SOPs)/guidelines in regard to expats and locals, and the topic of clinical research not conducting clinical trials, follows good clinical practice being so popular among the crowd, the phenomenon of (GCP), conducts training, and maintains an ethics clinical research has finally come into the picture in UAE. committee as per GCP standards. The clinical research sector in UAE is currently going well within the country, with many pharmaceutical companies investing in studies, with the patient pool consisting of the population in the Middle East. Geography of the United Arab Emirates UAE is bordered by the Arab Gulf to the north, the Gulf of Oman and the Sultanate of Oman to the east, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Sultanate of Oman to the south, and the State of Qatar and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to the west. Dubai Health Authority Medical Research Committee (MRC) acts as an institutional review board at Dubai Health Authority.2 The primary objective of the MRC is to protect the mental and physical welfare, rights, dignity and safety of participants in research, to facilitate ethical research through efficient and effective review processes, to promote ethical standards of human research, and to review research in accordance with the DHA code of Population: 9.206 million1 ethics and the ICHGCP guidelines, ensuring that all such investigations conform to ethical principles including Introduction those described in the Declaration of Helsinki. With such a diverse population in the United Arab Emirates, and the diversity of languages as well, communication is not an issue among the people. -

Clinic Al Noor Medical Center

City Type Provider Name Area Address Contact Number Fax Number Code AAN(03) Clinic Al Noor Medical Center - AAN Murabba Main St., near Murabba round about, Al Ain 7662072 7662078 C703 AAN(03) Clinic Al Dhahery Clinic Central District Main street Central district, Al Ain 7656882 7668619 C419 AAN(03) Clinic Emirates Clinic & Medical Services Centre Al Ain Main St. Al Ain Main St., AAN 7644744 7667930 C090 AAN(03) Clinic Al Raneen Medical Center - AAN Murabba M-2 Lucky Plaza Bldg., nr. Hayath Center, Zayed Bin Sultan St.,, Murabba new signal, Al Ain 7655602 7655603 C663 AAN(03) Clinic Al Farabi Medical Center L.L.C. (Ex: Al Farabi Medical Clinic) Al Ain Main St. Al Ain Main St. AAN 7515383 7511262 C086 AAN(03) Clinic Sultan Medical Centre - AAN Sheikh Zayed Al Ain Sheik Zyed Bin Sul St. Mohd Sultaan Al Nyadi Building 7641525 7510100 C567 AAN(03) Clinic Hamdan Medical Centre Hilton Hilton Street 7654797 7654437 C092 AAN(03) Clinic Al Meena Medical Centre Hamdan Aminahamda, near UAE Exchange, Aboobacker Sidhiq Road, Main Street 7800762 7800763 C1189 AJM(06) Clinic Nuaimia Clinic New Sanaiya Opp Suncity Supermarket ,New Sanaiya, Ajman 7432292 7430369 C528 AJM(06) Clinic National Clinic - AJM Near GMC Hospital Near GMC Hospital, Lucy R/A, Ajman 7480780 7430369 C529 AJM(06) Clinic Al Sanaiya Clinic-AJM Industrial Area Pepico Complex, Jurf Industrial Area Near China Mall, Sharjah 7484078 7430369 C530 AJM(06) Clinic Advanced Medical Centre-Ajman Al Bustan Flat # 202, 2nd Fr, City Mart Bldg, Opp to Ajman Municipality, Sheikh Rashid Bin Humaid Street, Al Bustan, Ajman 7459969 7459919 C462 AJM(06) Clinic Sarah Medical Clinic Muzeira, 1st Floor - Rashed Amer Rashed Saeed Al Badawawi Bldg., Hatta Rd, Muzeira, Ajman 8522116 8522126 C451 AJM(06) Clinic Aaliya Medical Centre Above Al Manama HyperMarket,opp Kuwait hospital,Al Shaab Buldg. -

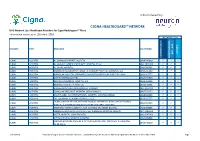

CIGNA HEALTHGUARDSM NETWORK UAE Network List - Healthcare Providers for Cigna Healthguardsm Plans Information Correct As of 11Th April, 2018 NETWORK TIER

administered by: CIGNA HEALTHGUARDSM NETWORK UAE Network List - Healthcare Providers for Cigna HealthguardSM Plans Information correct as of 11th April, 2018 NETWORK TIER EMIRATE TYPE PROVIDER TELEPHONE GENERAL EXCL. AHD COMPREHENSIVE COMPREHENSIVE DUBAI HOSPITAL AL GARHOUD PRIVATE HOSPITAL (04)4545000 DUBAI HOSPITAL AL JALILA CHILDREN’S SPECIALTY HOSPITAL FZ LLC (04) 2811000 DUBAI HOSPITAL AL ZAHRA HOSPITAL (04)3786666 DUBAI HOSPITAL AMERICAN ACADEMY OF COSMETIC SURGERY HOSPITAL (AACSH) FZ LLC (04)4237600 DUBAI HOSPITAL AMERICAN HOSPITAL (DERMATOLOGY NOT COVERED ON DIRECT BILLING) (04)3367777 DUBAI HOSPITAL ASTER HOSPITAL (ASTER) (04)3814800 DUBAI HOSPITAL BELHOUL EUROPEAN HOSPITAL LLC (04)3454000 DUBAI HOSPITAL BELHOUL SPECIALITY HOSPITAL (04)2140301 DUBAI HOSPITAL BURJEEL HOSPITAL FOR ADVANCED SURGERY (04) 4070100 DUBAI HOSPITAL CANADIAN SPECIALIST HOSPITAL DEIRA BRANCH (04)7072222 DUBAI HOSPITAL CEDARS JEBEL ALI INTERNATIONAL HOSPITAL ( CEDARS GROUP) (04)8814000 DUBAI HOSPITAL DR. SULAIMAN AL HABIB HOSPITAL FZ-LLC (04)4297777 DUBAI LONDON SPECIALTY HOSPITAL (ALSO KNOWN AS DUBAI LONDON CLINIC) DUBAI HOSPITAL (04)3782999 (DENTAL & DERMATOLOGY NOT COVERED ON DIRECT BILLING) DUBAI HOSPITAL EMIRATES HOSPITAL (DENTAL NOT COVERED ON DIRECT BILLING) (04)3496666 DUBAI HOSPITAL EMIRATES SPECIALITY HOSPITAL FZ LLC (EMIRATES HOSPITAL GROUP) (04) 2484500 DUBAI HOSPITAL HATTA HOSPITAL ( DHA FACILITY) (04) 8147000 DUBAI HOSPITAL INTERNATIONAL MODERN HOSPITAL (04)3988888 IRANIAN HOSPITAL (DENTAL & OPTICAL -

United Arab Emirates

Parcel Post Compendium Online AE - United Arab Emirates Emirates Post Group AEA Basic Services CARDIT Carrier documents international No transport – origin post 1 Maximum weight limit admitted RESDIT Response to a CARDIT – destination No 1.1 Surface parcels (kg) 30 post 1.2 Air (or priority) parcels (kg) 30 6 Home delivery 2 Maximum size admitted 6.1 Initial delivery attempt at physical No delivery of parcels to addressee 2.1 Surface parcels 6.2 If initial delivery attempt unsuccessful, 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m No card left for addressee (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 6.3 Addressee has option of paying taxes or No 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m No duties and taking physical delivery of the (or 3m length & greatest circumference) item 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Yes 6.4 There are governmental or legally No (or 2m length & greatest circumference) binding restrictions mean that there are certain limitations in implementing home 2.2 Air parcels delivery. 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m No 6.5 Nature of this governmental or legally (or 3m length & greatest circumference) binding restriction. 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m No (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Yes 7 Signature of acceptance (or 2m length & greatest circumference) 7.1 When a parcel is delivered or handed over Supplementary services 7.1.1 a signature of acceptance is obtained Yes 3 Cumbersome parcels admitted No 7.1.2 captured data from an identity card are Yes registered 7.1.3 another form of evidence of receipt is No Parcels service features obtained 5 Electronic exchange -

Seha Announces Its Operational Hours for Hirji New Year Holiday

SEHA ANNOUNCES ITS OPERATIONAL HOURS FOR HIRJI NEW YEAR HOLIDAY COVID-19 Drive-Through Screening Facilities will remain operational from 10:00am – 8:00pm Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. August 11, 2021: Abu Dhabi Health Services Company, (SEHA), the UAE’s largest healthcare network, has announced its operational hours during the Islamic New Year holiday, observed August 12, 2021. Al Ain Hospital Hijri New Year Holiday Department August 12, 2021 Emergency Department 24/7 Outpatient Clinics Closed Corniche Hospital Hijri New Year Holiday Department August 12, 2021 ER / In-Patients 24/7 OPD WHC Pharmacy Closed SPR Clinic PCR Employee screening center (HR) SEHA Kidney Care Hijri New Year Holiday Department August 12, 2021 SKC Central SKC Abu Dhabi 7:00am – 11:00pm SKC Al Ain Dialysis Units Madinat Zayed 7:00am – 11:00pm at Al Dhafra Ghayathi 7:00am to 7:00pm Hospitals Liwa, Silaa, Delma 7:00am to 7:00pm Outpatient clinics, Telemedicine and Pharmacy Closed Sheikh Khalifa Medical City / Al Rahba Hospital Hijri New Year Holiday Department August 12, 2021 Emergency Department (SKMC) 24/7 Outpatient Clinics (SKMC) Closed Occupational Health Clinic (SKMC) Admission Office (SKMC) BSP Outpatient Clinics (RH) Emergency Department (RH) Sheikh Shakbout Medical City Hijri New Year Holiday Department August 12, 2021 Occupational Health Clinic 8:00am - 5:00pm Injection Clinic and Dressing Tawam Hospital Hijri New Year Holiday Department August 12, 2021 Pharmacy 24/7 ER OPD Closed Abu Dhabi & Al Ain & Al Dhafra Blood Bank Hijri New Year Holiday Department -

United Arab Emirates

ANY INTERNATIONAL BANK (SWIFT CODE): TLBPPHMM OVERSEAS PARTNERS DIRECTORY as of August 06, 2019 United Arab Emirates Remittance Partner Address Branch Name Country Contact Number AL ANSARI EXCHANGE Level 7, Al Ansari Business Center, Al Barsha 1, Beside Mall of Head Office Dubai, United Arab Emirates +971-4-377-2777 the Emirates P.O.Box 6176, Dubai, UAE +971-4-354-9592 [email protected] AL AHALIA EXCHANGE Al Ahalia Money Exchange Bureau Sharjah 1 Branch, Rolla – Sharjah 1 Branch Sharjah,United Arab Emirates 00971-06-5626766 Sharjah, UAE. 00971-06-5623624 [email protected] AL AHALIA EXCHANGE Al Ahalia Money Exchange Bureau Sharjah 2 Branch Khan Saheb Sharjah 2 (Industrial) Sharjah,United Arab Emirates 00971-06-5353311 Building Sharjah Industrial Area- 10, Near GECO Round About, 00971-06-5353322 Old Skyline College Road P.O.Box: 28720 Sharjah, UAE [email protected] AL AHALIA EXCHANGE Al Ahalia Money Exchange Bureau P.O.Box : 17411 Fatima Mall Fathima Mall Ajman Ajman,United Arab Emirates 06-7499781 (inside shop) Opp. GMC Hospital Ajman, UAE 06-7499841 [email protected] AL AHALIA EXCHANGE Al Ahalia Money Exchange Bureau P.O.Box : 28720 Al Nahda Al Nahda Sharjah Branch Sharjah,United Arab Emirates 00971-06-5549924 Park Opp. Lulu Hyper Market Behind KFC, Sharjah, UAE 00971-06-5548758 [email protected] AL AHALIA EXCHANGE Al Ahalia Money Exchange Bureau Madinat Zayed Branch Near Madinat Zayed Branch Abu Dhabi,United Arab Emirates 00971-2-8848955 Rulers Court & NBAD P.B. No. 2419 Madinat Zayed, Abudhabi 00971-2-8848994 [email protected] AL AHALIA EXCHANGE Al Ahalia Money Exchange Bureau Mussafah Branch, Shop No: 4 Mussafah Abu Dhabi,United Arab Emirates 00971-2-5546644 & 5, M6 P.B. -

Geological Passport New

ﻣﺪﺧﻞ ﻟﺠﻴﻮﻟﻮﺟﻴﺔ ﺩﻭﻟﺔ ﺍﻹﻣﺎﺭﺍﺕ ﺍﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪﺓ www.moei.gov.ae - 59 +971 2 6190000 8006634 +971 2 6190001 [email protected] www.moei.gov.ae © ﺟﻴﻮﻟﻮﺟﻴﺔ ﺩﻭﻟﺔ ﺍﻹﻣﺎﺭﺍﺕ ﺍﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪﺓ 283,600 56°30 51 26°3022 (1) 1 600 10 2 (2) (3) 3 (4) 4 – 5 Ministry of Energy & Industry (Salt Domes)(6) (Magnetic Data of UAE)(7) 6 (8) (Dhera Formation – Dibba- Al Fujairah) (9) (Simplified Geological Map for Northern UAE) 7 D4(10) 8 The UAE Geological App: mGeology mGeology is a free mobile app that puts the geology of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) at your fingertips! It provides easy, interactive access to the UAE Ministry of Energy & Industry’s (MOEI) full national coverage geological mapping (1:100,000 scale). Search for where you live or any other placename. Alternatively, use GPS (if enabled) to zoom to your current location. Tap on the map and reveal details of the rocks beneath your feet. Geology is very much a field-orientated science, and mGeology will help you to understand geology whilst outside in that landscape. mGeology provides digital mapping for UAE surface geology. It also displays the presence of sabkha and veneer deposits. Geological cross sections, photographs and access to purchase a range of geology mapping products from the MOEI website are also provided. 24 3D Geology A 3D digital geological model of Abu Dhabi City was produced from surface evidence and borehole data provided by Abu Dhabi Municipality. Layered 3D Geology Model of Abu Dhabi Magnetic & Gravity Data Sander Geophysics Ltd acquired airborne gravity and magnetic data and integrated it with legacy ground based gravity data and offshore airborne magnetic data provided from different resources. -

Where Are the COVID-19 Test Centres in the UAE and How You Can Book a Test?

Where are the COVID-19 Test Centres in the UAE and How You Can Book a Test? The UAE has set up numerous COVID-19 (Coronavirus) test centres throughout the country, in addition to testing facilities at various Government healthcare facilities. This is part of an effort to step up testing patients for COVID-19 in order to “flatten the curve” in the UAE. Can I Get Tested? If you are showing symptoms of COVID-19, you need to consult a medical professional immediately (see table on the following pages for telephone numbers). Dubai Health Authority (DHA) has set out guidelines on when, where and how to get a COVID-19 test in Dubai. These guidelines are issued to prevent undue concern by clarifying that not everyone needs to take a COVID-19 test. Please note, that while the current guidance does not mandate everyone to be tested, these guidelines may change in the future. If you have come in contact with a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient, you should first self- quarantine at home and then call the DHA helpline at the number provided on subsequent pages. According to Dr Abdulla Al Rasasi (Head of Preventive Medicine at DHA), patients are suspected to have the virus if they have: Upper or lower respiratory systems (cough and difficulty breathing) with or without fever Travelled to a high-risk country Cared for or come into contact with people with COVID-19 Severe acute respiratory infections with no other medical explanation Vulnerable groups are at a higher risk of serious infection with the virus. -

Global Patterns and Environmental Controls of Perchlorate and Nitrate Co-Occurrence in Arid and Semi-Arid Environments W

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln NASA Publications National Aeronautics and Space Administration 2015 Global patterns and environmental controls of perchlorate and nitrate co-occurrence in arid and semi-arid environments W. Andrew Jackson Texas Tech University, [email protected] J. K. Böhlke U.S. Geological Survey, 431 National Center, Reston, VA Brian J. Andraski U.S. Geological Survey, 2730 N. Deer Run Rd, Carson City, NV Lynne Fahlquist U.S. Geological Survey, 1505 Ferguson Ln, Austin, TX Laura Bexfield U.S. Geological Survey, 5338 Montgomery Blvd. NE, Suite 400, Albuquerque, NM See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nasapub Jackson, W. Andrew; Böhlke, J. K.; Andraski, Brian J.; Fahlquist, Lynne; Bexfield, Laura; Eckardt, Frank D.; Gates, John B.; Davila, Alfonso F.; McKay, Christopher P.; Rao, Balaji; Sevanthi, Ritesh; Rajagopalan, Srinath; Estrada, Nubia; Sturchio, Neil; Hatzinger, Paul B.; Anderson, Todd A.; Orris, Greta; Betancourt, Julio; Stonestrom, David; Latorre, Claudio; Li, Yanhe; and Harvey, Gregory J., "Global patterns and environmental controls of perchlorate and nitrate co-occurrence in arid and semi-arid environments" (2015). NASA Publications. 210. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nasapub/210 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in NASA Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors W. Andrew Jackson, J. K. Böhlke, Brian J. Andraski, Lynne Fahlquist, Laura Bexfield, Frank D. Eckardt, John B. Gates, Alfonso F.