Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

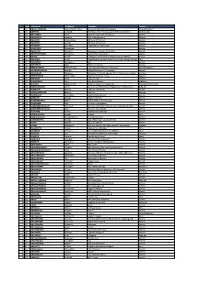

Final List EMD2015 02062015

N° Title LastName FirstName Company Country 1 Dr ABDUL RAHMAN Noorul Shaiful Fitri Universiti Malaysia Terengganu United Kingdom 2 Mr ABSPOEL Lodewijk Nl Ministry For Infrastructure And Environment Netherlands 3 Mr ABU-JABER Nizar German Jordanian University Jordan 4 Ms ADAMIDOU Despina Een -Praxi Network Greece 5 Mr ADAMOU Christoforos Ministry Of Tourism Greece 6 Mr ADAMOU Ioannis Ministry Of Tourism Greece 7 Mr AFENDRAS Evangelos Independent Consultant Greece 8 Mr AFENTAKIS Theodoros Greece 9 Mr AGALIOTIS Dionisios Vocational Institute Of Piraeus Greece 10 Mr AGATHOCLEOUS Panayiotis Cyprus Ports Authority Cyprus 11 Mr AGGOS Petros European Commission'S Representation Athens Greece 12 Dr AGOSTINI Paola Euro-Mediterranean Center On Climate Change (Cmcc) Italy 13 Mr AGRAPIDIS Panagiotis Oss Greece 14 Ms AGRAPIDIS Sofia Rep Ec In Greece Greece 15 Mr AHMAD NAJIB Ahmad Fayas Liverpool John Moores University United Kingdom 16 Dr AIFANDOPOULOU Georgia Hellenic Institute Of Transport Greece 17 Mr AKHALADZE Mamuka Maritime Transport Agency Of The Moesd Of Georgia Georgia 18 Mr AKINGUNOLA Folorunsho Nigeria Merchant Navy Nigeria 19 Mr AKKANEN Mika City Of Turku Finland 20 Ms AL BAYSSARI Paty Blue Fleet Group Lebanon 21 Dr AL KINDI Mohammed Al Safina Marine Consultancy United Arab Emirates 22 Ms ALBUQUERQUE Karen Brazilian Confederation Of Agriculture And Livesto Belgium 23 Mr ALDMOUR Ammar Embassy Of Jordan Jordan 24 Mr ALEKSANDERSEN Øistein Nofir As Norway 25 Ms ALEVRIDOU Alexandra Euroconsultants S.A. Greece 26 Mr ALEXAKIS George Region Of Crete -

Download This PDF File

Culture Golfo Maggini University of loannina Contemporary Greek Philosophy at the Crossroads: Neokantianism - Existentialism - Phenomenology Abstract During the first two decades of the 20th century, Greece’s philosophical scene was dominated by neokantianism. In the so called “Heidelberg group” of philosophers we come across a company of people educated in post-WW 1 Germany, close to some of the most influential philosophers of their time. Immersed in neokantianism, the triad Theodorakopoulos-Tsatsos-Kanello- poulos served the spirit of this philosophical school not just within the uni versity classroom, but also for a much wider public. Within this dominant framework, what was the role and significance of other philosophical trends, such as phenomenology, in the genesis of contemporary Greek philosophy? The main working hypothesis of our research is that the phenomenological movement in Greece was caught since its beginning in the tension between two dominant philosophical currents, neokantianism and existentialism. A more serious effort to cope with phenomenological thought on a systematic basis began in the 1980s. It was accompanied by the increasing recognition of phenomenology as an autonomous field of European philosophy within the Greek academic community. We will then try to demonstrate that this was contingent to the way in which Greek philosophy evolved in the 20th century, inside as well as outside the academia. 345 Culture Small has been the number of publications on the evolution of 20th century Greek philosophy. This is due to many factors, including the obvi ous gap between the ex cathedra philosophy teachers, who determined the identity of Greek academic philosophy, and the dynamism and profusion of many “paraphilosophical” occurrences. -

A Journal for Greek Letters Crisis, Criticism and Critique in Contemporary Greek Studies

Vol. 16-17 B 2013 - 2014 Introduction a Journal for Greek letters Crisis, Criticism And Critique In Contemporary Greek Studies Editors Vrasidas Karalis and Panayota Nazou 1 Vol. 16-17 B 2013 - 2014 a Journal for Greek letters Crisis, Criticism And Critique In Contemporary Greek Studies Editors Vrasidas Karalis and Panayota Nazou The Modern Greek Studies Το περιοδικό φιλοξενεί άρθρα στα Αγγλικά και τα Ελληνικά Association of Australia and αναφερόμενα σε όλες τις απόψεις των Νεοελληνικών Σπουδών New Zealand (MGSAANZ) (στη γενικότητά τους). Υποψήφιοι συνεργάτες θα πρέπει να υποβάλλουν κατά προτίμηση τις μελέτες των σε δισκέτα και σε President - Anthony Dracopoulos έντυπη μορφή. Όλες οι συνεργασίες από πανεπιστημιακούς έχουν Vice President - Elizabeth Kefallinos υποβληθεί στην κριτική των εκδοτών και επιλέκτων πανεπιστημι- Treasurer - Panayota Nazou ακών συναδέλφων. Secretary - Panayiotis Diamadis The Modern Greek Studies Association of Australia and New Published for the Modern Greek Studies Association of Zealand (MGSAANZ) was founded in 1990 as a professional Australia and New Zealand (MGSAANZ) association by those in Australia and New Zealand engaged in Modern Greek Studies. Membership is open to all interested Department of Modern Greek, University of Sydney NSW in any area of Greek studies (history, literature, culture, tradi- 2006 Australia tion, economy, gender studies, sexualities, linguistics, cinema, T (02) 9351 7252 F (02) 9351 3543 Diaspora etc.). [email protected] The Association issues a Newsletter (Ενημέρωση), holds conferences and publishes two journals annually. ISSN 1039-2831 Editorial board Copyright Vrasidas Karalis (University of Sydney) Copyright in each contribution to this journal belongs to its Maria Herodotou (La Trobe University) author. -

National and Kapodistrian University of Αthens

NATIONAL AND KAPODISTRIAN UNIVERSITY OF ΑTHENS SCHOOL OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY PEDAGOGY & PSYCHOLOGY UNDERGRADUATE & POSTGRADUATE GUIDE OF STUDIES 2012 - 2013 NATIONAL AND KAPODISTRIAN UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS SCHOOL OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY, PEDAGOGY AND PSYCHOLOGY UNDERGRADUATE & POSTGRADUATE STUDY GUIDE Academic Year 2012-2013 ATHENS 2012 2 Editorial Team for the Study Guide Chair: Georgios I. Spanos, Professor, Department of Pedagogy Members responsible for the Greek version: Georgios Steiris, Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy Maria-Zoe Fountopoulou, Associate Professor, Department of Pedagogy Petros Roussos, Assistant Professor, Psychology Programme Members responsible for the English version: Evangelos Protopapadakis, Lecturer, Department of Philosophy Athanasios Verdis, Lecturer, Department of Pedagogy Asimina Ralli, Lecturer, Department of Psychology Formatting - Typesetting: Katerina Stamatidou ΓΙΚΟ ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ ΚΥΠΡΟΥ Αρχιεπισκόπου Κυπριανού 31 Τ.Θ. 50329, 3603 Λ PRINTING: DEPARTMENT OF PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS PRINTING OFFICE 5, STADIOU STR. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS INFORMATION FOR NEW STUDENTS .......................................................................................................... 7 HISTORY AND STRUCTURE ........................................................................................................................... 9 GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................................................................................... -

Challenges in Greek Education During the 1960S: the 1964 Educational Reform and Its Overthrow

Cómo referenciar este artículo / How to reference this article Foukas, V. (2018). Challenges in Greek education during the 1960s: the 1964 educational reform and its overthrow. Espacio, Tiempo y Educación, 5(1), pp. 71-93. doi: http://dx.doi. org/10.14516/ete.215 Challenges in Greek education during the 1960s: the 1964 educational reform and its overthrow Vassilis Foukas e-mail: [email protected] Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Greece Abstract: In Greece, during the 1960s a new period began which marked a break with the past and the start of a new approach for the future. After the post-war period, Greek society began to balance the State budget and create the conditions for the country’s accession to the European Common Market. This was the context in which, in 1964, the second meaningful educational reform of the 20th century was attempted. However, in 1965, the educational reform was quickly blocked on account of the unstable political situation and the imminent dictatorship. This paper examines the changes in Education adopted as part of the 1964 educational reform within their historical and political context, and provides an overview of the major political and educational events that led to their early overthrow in 1965. Keywords: educational reform; modernization; democratization; Greek education; educational policy. Recibido / Received: 11/11/2017 Aceptado / Accepted: 05/12/2017 1. Introduction After the Second World War, several European countries made systematic efforts to adjust their Education systems based on the post-war political, economic and social plans1. In particular, the emphasis was given to the principle of equal opportunities in education, the welfare state and social justice, and schooling was seen as a lever for social and economic development and progress2. -

The Crisis of Historicism and the Correlation Between Nationalism and Neo-Kantian Philosophy of History in the Interwar Period

History Research, July-Sep., 2015, Vol. 5, No. 3, 141-155 doi: 10.17265/2159-550X/2015.03.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Crisis of Historicism and the Correlation Between Nationalism and Neo-Kantian Philosophy of History in the Interwar Period Kate Papari University of Athens, Greece Recent historiographic studies of cultural exchanges between Germany and Greece in the 19th and 20th centuries have tended to neglect the mutual influence of the two countries’ intellectuals; as a result, there is insufficient appreciation of the extent to which historiography and philosophy were appropriated by the politics of the Interwar period. This article focuses on attempts by neo-Kantian philosophers to overcome the crisis of historicism, and on the impact of this crisis on Greek intellectuals’ perceptions of historicism. The study shows that at the time historicism invoked the past to solve the problems of the present. My purpose is to show that in a time of crisis, Germany’s pursuit of its Greekness in conformity with the Bildung tradition, and Greece’s cultural dependence on Germany in the meaning-making of its own Greekness, shared common ground in the ideological uses of philosophy and history in the service of politics and the politics of culture. In the aftermath of WWI, German scholars raised the issue of the crisis of historicism. Neo-Kantian philosophers such as Heinrich Rickert, whose theory had a major impact on Greek intellectuals, became involved in this debate, posing the question of historical objectivity. Yet Rickert’s philosophy of history soon fell into an impasse, leading to the rise of an idealist philosophy of history in the 1930s that committed itself anew to the dominant politics. -

Modern Greek Studies Yearbook

MODERN GREEK STUDIES YEARBOOK * A PUBLICATION OF MEDITERRANEAN, SLAVIC. AND EASTERN ORTHODOX STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Volume 20/21 2004/2005 MODERN GREEK STUDIES YEARBOOK A PUBLICATION OF MEDITERRANEAN, SLAVIC AND EASTERN ORTHODOX STUDIES Editor: THEOFANIS G. STAVROU University of Minnesota Editorial Board: Grigorii L. Arsh Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow Maria Couroucli Fatima Eloeva CNRS - University of Paris X, Nanterre University of St. Petersburg Peter Mackridge Christos G. Patrinelis University of Oxford University ofThessaloniki Olga E. Petrunina Vincenzo Rotolo Lomonosov State University, Moscow University of Palermo Nassos Vayenas University of Athens UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Minneapolis, Minnesota Volume 20/21 2004/2005 Cover Illustration: Founding members of the Parnassos Literary Society Responsibility for tbe production of this volume: Theofanis G. Stavrou, editor Soterios G. Stavrou. associate editor Elizabeth A. Harry, assistant editor The Modern Greek Studies Yearbook is published by the Modern Greek Studies Program at the University of Minnesota. The price for this volume is $60.00. Checks should be made payable to the Modern Greek Studies Yearbook, and sent to: Modern Greek Studies 325 Social Sciences Building University of Minnesota 267-19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 Telephone: (612) 624-4526 FAX: (612) 626-2242 E-mail: [email protected] The main objective of the Modern Greek Studies Yearbook is the dissemination of scholarly information in the field of modern Greek studies. The field is broadly defined to include the social sciences and the humanities, indeed any body of knowledge that touches on the modern Greek experience. Topics dealing with earlier periods, the Byzantine and even the Classical, will be considered provided they relate, in some way, to aspects of later Greek history and culture.