Village Atlas Section 22, Glossary and Bibliography.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malhamdale and Southern/South Western Dales Fringes

Malhamdale and Southern/South Western Dales Fringes + Physical Influences Malhamdale The landscape of Malhamdale is dominated by the influence of limestone, and includes some of the most spectacular examples of this type of scenery within the Yorkshire Dales National Park and within the United Kingdom as a whole. Great Scar limestone dominates the scenery around Malham, attaining a thickness of over 200m. It was formed in the Carboniferous period, some 330 million years ago, by the slow deposition of shell debris and chemical precipitates on the floor of a shallow tropical sea. The presence of faultlines creates dramatic variations in the scenery. South of Malham Tarn is the North Craven Fault, and Malham Cove and Gordale Scar, two miles to the south, were formed by the Mid Craven Fault. Easy erosion of the softer shale rocks to the south of the latter fault has created a sharp southern edge to the limestone plateau north of the fault. This step in the landscape was further developed by erosion during the various ice ages when glaciers flowing from the north deepened the basin where the tarn now stands and scoured the rock surface between the tarn and the village, leading later to the formation of limestone pavements. Glacial meltwater carved out the Watlowes dry valley above the cove. There are a number of theories as to the formation of the vertical wall of limestone that forms Malham Cove, whose origins appear to be in a combination of erosion by ice, water and underground water. It is thought that water pouring down the Watlowes valley would have cascaded over the cove and cut the waterfall back about 600 metres from the faultline, although this does not explain why the cove is wider than the valley above. -

The Monkwearmouth College, Sunderland and Wearside College, Sunderland (Dissolution) Order 1996

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1996 No. 1764 EDUCATION, ENGLAND AND WALES The Monkwearmouth College, Sunderland and Wearside College, Sunderland (Dissolution) Order 1996 Made - - - - 8th July 1996 Laid before Parliament 9th July 1996 Coming into force - - 1st August 1996 Whereas the Secretary of State for Education and Employment has received a proposal from the Further Education Funding Council for England, made in accordance with section 51 of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992(1) (“the Act”), for the dissolution under section 27 of the Act of the further education corporations known as Monkwearmouth College, Sunderland and Wearside College, Sunderland(2) (“the Old Corporations”); Now therefore in exercise of the power conferred on her by section 27 of the Act the Secretary of State after consulting the Old Corporations and with the consent of the further education corporation known as City of Sunderland College(3) (“the New Corporation”) hereby makes the following Order: 1. This Order may be cited as The Monkwearmouth College, Sunderland and Wearside College, Sunderland (Dissolution) Order 1996 and shall come into force on 1st August 1996. 2. On 1st August 1996 the Old Corporations shall be dissolved and all of their respective property, rights and liabilities shall be transferred to the New Corporation, being a body corporate established for purposes which include the provision of educational facilities or services. 3. Section 26(2), (3) and (4) of the Act shall apply to any person employed by either of the Old Corporations immediately before 1st August 1996 as if the references in that section— (a) to a person to whom that section applies were to a person so employed; (b) to the operative date were to 1st August 1996; (c) to the transferor were to either of the Old Corporations (as the case may be); and (d) to the corporation were to the New Corporation. -

Directions to Sunderland Civic Centre

Directions to Sunderland Civic Centre From: North : Route: Tyne Tunnel/A19 and join A1231 to Sunderland, crossing over A19. Depart Tyne Tunnel and follow A19 Sunderland for Follow A1231 City Centre signposting, for approx. 4 Local transport appox. 4 miles. Take A1231 Sunderland/Gateshead exit miles, crossing the river. Then follow the signs for services and turn left at the roundabout (A1231 Sunderland). Teeside (A19) and at the 4th set of traffic signals turn Follow A1231 City Centre signposting, for approx. 4 left, signposted Civic Centre is on the left-hand side. miles, crossing the river. Then follow the signs for Airports Teeside (A19) and at the 4th set of traffic signals turn From: Durham : Route: A690 Newcastle left, signposted Civic Centre. The Civic Centre is on the From: South : Route: A1 or A19/A690 35 minutes drive left-hand side. Join A690 Sunderland and follow the signs for City Durham Tees Valley Centre A690. Take 3rd exit at the signalised 45 minutes drive From: Newcastle Airport : Route: A69/A1 roundabout, signposted Teeside (A19) and at the 4th Depart Newcastle Airport on A696 for 1 mile then join set of traffic signals turn left, signposted for Civic Rail stations A1/A69 (South) for approx. 6 miles (past Metrocentre). Centre. The Civic Centre is on the left-hand side. Intercity Take first Sunderland exit, turn right at the roundabout • Newcastle • Durham Local • Sunderland Newcastle (Local for Sunderland, A49 upon Tyne TYNESIDE National Glass Centre change at Newcastle River Tyne Central Station, journey Sunderland From Seaburn, Roker WEARSIDE & South Shields time approx. -

Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd

Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd ANGOR UNIVERSITY Excavations, July and August 2013 Karl, Raimund; Waddington, Kate Published: 01/01/2015 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Karl, R., & Waddington, K. (2015). Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd Excavations, July and August 2013: Interim report. (Bangor Studies in Archaeology; Vol. 12). Bangor University. Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 09. Oct. 2020 Characterising the Double Ringwork Enclosures of Gwynedd: Meillionydd Excavations July and August 2013 Interim Report Kate Waddington and Raimund Karl Bangor: Gwynedd, January 2016 Bangor Studies in Archaeology Report No. 12 Bangor Studies in Archaeology Report No. 1 2 Also available in this series: Report No. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

Contracts Awarded Sep 14 to Jun 19.Xlsx

Contracts, commissioned activity, purchase order, framework agreement and other legally enforceable agreements valued in excess of £5000 (January - March 2019) VAT not SME/ Ref. Purchase Contract Contract Review Value of reclaimed Voluntary Company/ Body Name Number order Title Description of good/and or services Start Date End Date Date Department Supplier name and address contract £ £ Type Org. Charity No. Fairhurst Stone Merchants Ltd, Langcliffe Mill, Stainforth Invitation Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 1 PO113458 Stone supply for Brackenbottom project Supply of 222m linear reclaimed stone flags for Brackenbottom 15/07/2014 17/10/2014 Rights of Way Road, Langcliffe, Settle, North Yorkshire. BD24 9NP 13,917.18 0.00 To quote SME 7972011 Hartlington fencing supplies, Hartlington, Burnsall, Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 2 PO113622 Woodhouse bridge Replacement of Woodhouse footbridge 13/10/2014 17/10/2014 Rights of Way Skipton, North Yorkshire, BD23 6BY 9,300.00 0.00 SME Mark Bashforth, 5 Progress Avenue, Harden, Bingley, Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 3 PO113444 Dales Way, Loup Scar Access for all improvements 08/09/2014 18/09/2014 Rights of Way West Yorkshire, BD16 1LG 10,750.00 0.00 SME Dependent Historic Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 4 None yet Barn at Gawthrop, Dent Repair works to Building at Risk on bat Environment Ian Hind, IH Preservation Ltd , Kirkby Stephen 8,560.00 0.00 SME 4809738 HR and Time & Attendance system to link with current payroll Carval Computing Ltd, ITTC, Tamar Science Park, -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

Bunk Houses and Camping Barns

Finding a place to stay ……. Bunk Houses and Camping Barns To help you find your way around this unique part of the Yorkshire Dales, we have split the District into the following areas: Skipton & Airedale – taking in Carleton, Cononley, Cowling, Elslack, Embsay and Thornton-in-Craven Gargrave & Malhamdale – taking in Airton, Bell Busk, Calton, Hawkswick, Litton, and Malham Grassington & Wharfedale – taking in Bolton Abbey, Buckden Burnsall, Hetton, Kettlewell, Linton-in- Craven and Threshfield Settle & Ribblesdale – taking in Giggleswick, Hellifield, Horton-in-Ribblesdale, Long Preston, Rathmell and Wigglesworth Ingleton & The Three Peaks – taking in Chapel-le-Dale and Clapham Bentham & The Forest of Bowland taking in Austwick Grassington & Wharfedale Property Contact/Address Capacity/Opening Grid Ref/ Special Info Times postcode Barden Barden Tower, 24 Bunk Barn Skipton, BD23 6AS Mid Jan – End Nov SD051572 Tel: 01132 561354 www.bardenbunkbarn.co.uk BD23 6AS Wharfedale Wharfedale Lodge Bunkbarn, 20 Groups Lodge Kilnsey,BD23 5TP All year SD972689 www.wharfedalelodge.co.uk BD23 5TP [email protected] Grange Mrs Falshaw, Hubberholme, 18 Farm Barn Skipton, BD23 5JE All year SD929780 Tel: 01756 760259 BD23 5JE Skirfare John and Helen Bradley, 25 Inspected. Bridge Skirfare Bridge Barn, Kilnsey, BD23 5PT. All year SD971689 Groups only Dales Barn Tel:01756 753764 BD23 5PT Fri &Sat www.skirefarebridgebarn.co.uk [email protected] Swarthghyll Oughtershaw, Nr Buckden, BD23 5JS 40 Farm Tel: 01756 760466 All year SD847824 -

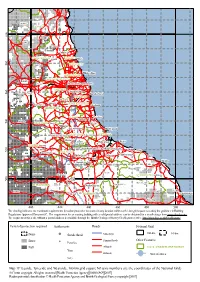

Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-Km Grid Square NZ (Axis Numbers Are the Coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown Copyright

Alwinton ALNWICK 0 0 6 Elsdon Stanton Morpeth CASTLE MORPETH Whalton WANSBECK Blyth 0 8 5 Kirkheaton BLYTH VALLEY Whitley Bay NORTH TYNESIDE NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE Acomb Newton Newcastle upon Tyne 0 GATESHEAD 6 Dye House Gateshead 5 Slaley Sunderland SUNDERLAND Stanley Consett Edmundbyers CHESTER-LE-STREET Seaham DERWENTSIDE DURHAM Peterlee 0 Thornley 4 Westgate 5 WEAR VALLEY Thornley Wingate Willington Spennymoor Trimdon Hartlepool Bishop Auckland SEDGEFIELD Sedgefield HARTLEPOOL Holwick Shildon Billingham Redcar Newton Aycliffe TEESDALE Kinninvie 0 Stockton-on-Tees Middlesbrough 2 Skelton 5 Loftus DARLINGTON Barnard Castle Guisborough Darlington Eston Ellerby Gilmonby Yarm Whitby Hurworth-on-Tees Stokesley Gayles Hornby Westerdale Faceby Langthwaite Richmond SCARBOROUGH Goathland 0 0 5 Catterick Rosedale Abbey Fangdale Beck RICHMONDSHIRE Hornby Northallerton Leyburn Hawes Lockton Scalby Bedale HAMBLETON Scarborough Pickering Thirsk 400 420 440 460 480 500 The shading indicates the maximum requirements for radon protective measures in any location within each 1-km grid square to satisfy the guidance in Building Regulations Approved Document C. The requirement for an existing building with a valid postal address can be obtained for a small charge from www.ukradon.org. The requirement for a site without a postal address is available through the British Geological Survey GeoReports service, http://shop.bgs.ac.uk/GeoReports/. Level of protection required Settlements Roads National Grid None Sunderland Motorways 100-km 10-km Basic Primary Roads Other Features Peterlee Full A Roads LOCAL ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT Yarm B Roads Water features Slaley Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-km grid square NZ (axis numbers are the coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown copyright. -

Tyne Catchment Flood Management Plan Policies and Measures for Managing Flood Risk Ouseburn Policy Unit

Tyne Catchment Flood Management Plan Policies and measures for managing flood risk Ouseburn policy unit Revision 2: February 2012 Policies and measures for managing flood risk: Lower Tyne Tidal policy unit 1 Revision 2: January 2012 We are the Environment Agency. It’s our job to look after your environment and make it a better place – for you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Working with business, Government and society as a whole, we are making your environment cleaner and healthier. The Environment Agency. Out there, making your environment a better place. Published by: Environment Agency Rivers House 21 Park Square South Leeds, West Yorkshire LS1 2QG Tel: 08708 506 506 © Environment Agency XX2012 All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. 2Policies and measures for managing flood risk: Lower Tyne Tidal policy unit Revision 2: January 2012 Introduction I am pleased to introduce the policy appraisal for the Ouseburn policy unit. This document provides the evidence for the preferred approach for managing flood risk, from all sources, within this policy area over the next 50 to 100 years and the measures required to implement this approach. The Tyne CFMP is listen to each others progress, discuss what one of 77 CFMPs has been achieved and consider where we for England and Wales. Through the CFMPs, may need to update parts of the CFMP. As we have assessed inland flood risk across all such this document remains ‘live’. -

Hetton Lodge, Hetton

Hetton Lodge, Hetton £635,000 Hetton Lodge Hetton, near Skipton BD23 6LR A CHARMING VILLAGE HOME OFFERING ELEGANT AND SPACIOUS THREE DOUBLE BEDROOMED ACCOMMODATION OF CHARACTER, WITH BEAUTIFUL AND SIZEABLE SOUTHERLY GARDENS AND TREMENDOUS VIEWS ACROSS TO THE FELLS. Set tow ards the westerly end of this desirable village, Hetton Lodge enjoys a fabulous location with beautifully manicured southerly gardens and magnificent views to Rylstone Fell. Inside, the accommodation offers great versatility and whilst some updating is required, it is nevertheless a very comfortable and elegant home of character, with potential to further extend if required (subject to a former planning consent being re-granted). The picturesque village of Hetton is without doubt one of the area's most sought after places in which to live, offering an attractive and desirable living environment amidst glorious National Park countryside. Home to the renowned award-w inning gastro pub The Angel Inn, the village is located just over 5 miles from both Skipton and Grassington, both of which offer a wide range of social and recreational amenities, and is in the catchment areas for both Upper Wharfedale school at Threshfield, and the nationally renowned Skipton Grammar Schools. Hetton Lodge is set on the western fringe of the village and is a typical Yorkshire stone 'long-house' with an attractive façade and good-sized through rooms, all of which have charm and elegance and face to the south, with all three reception rooms having garden doors out to the beautiful level gardens. Many of the w indows are double glazed, the property is heated by an oil-fired radiator system, and the accommodation is described in brief below using approximate room sizes:- GROUND FLOOR RECEPTION HALL Return staircase to first floor with open spindle balustrade.