Chapter 4: Sounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pg. 5 CHAPTER-2: MECHANISM of SPEECH PRODUCTION AND

Acoustic Analysis for Comparison and Identification of Normal and Disguised Speech of Individuals CHAPTER-2: MECHANISM OF SPEECH PRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1. Anatomy of speech production Speech is the vocal aspect of communication made by human beings. Human beings are able to express their ideas, feelings and emotions to the listener through speech generated using vocal articulators (NIDCD, June 2010). Development of speech is a constant process and requires a lot of practice. Communication is a string of events which allows the speaker to express their feelings and emotions and the listener to understand them. Speech communication is considered as a thought that is transformed into language for expression. Phil Rose & James R Robertson (2002) mentioned that voices of individuals are complex in nature. They aid in providing vital information related to sex, emotional state or age of the speaker. Although evidence from DNA always remains headlines, DNA can‟t talk. It can‟t be recorded planning, carrying out or confessing to a crime. It can‟t be so apparently directly incriminating. Perhaps, it is these features that contribute to interest and importance of forensic speaker identification. Speech signal is a multidimensional acoustic wave (as seen in figure 2.1.) which provides information about the words or message being spoken, speaker identity, language spoken, physical and mental health, race, age, sex, education level, religious orientation and background of an individual (Schetelig T. & Rabenstein R., May 1998). pg. 5 Acoustic Analysis for Comparison and Identification of Normal and Disguised Speech of Individuals Figure 2.1.: Representation of properties of sound wave (Courtesy "Waves". -

Phonological Use of the Larynx: a Tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière

Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière To cite this version: Jacqueline Vaissière. Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial. Larynx 97, 1994, Marseille, France. pp.115-126. halshs-00703584 HAL Id: halshs-00703584 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00703584 Submitted on 3 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Vaissière, J., (1997), "Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial", Larynx 97, Marseille, 115-126. PHONOLOGICAL USE OF THE LARYNX J. Vaissière UPRESA-CNRS 1027, Institut de Phonétique, Paris, France larynx used as a carrier of paralinguistic information . RÉSUMÉ THE PRIMARY FUNCTION OF THE LARYNX Cette communication concerne le rôle du IS PROTECTIVE larynx dans l'acte de communication. Toutes As stated by Sapir, 1923, les langues du monde utilisent des physiologically, "speech is an overlaid configurations caractéristiques du larynx, aux function, or to be more precise, a group of niveaux segmental, lexical, et supralexical. Nous présentons d'abord l'utilisation des différents types de phonation pour distinguer entre les consonnes et les voyelles dans les overlaid functions. It gets what service it can langues du monde, et également du larynx out of organs and functions, nervous and comme lieu d'articulation des glottales, et la muscular, that come into being and are production des éjectives et des implosives. -

Relations Between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations

14 Relations between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations Willem J. M. Levelt One Agent, Two Modalities There is a famous book that never appeared: Bever and Weksel (shelved). It contained chapters by several young Turks in the budding new psycho- linguistics community of the mid-1960s. Jacques Mehler’s chapter (coau- thored with Harris Savin) was entitled “Language Users.” A normal language user “is capable of producing and understanding an infinite number of sentences that he has never heard before. The central problem for the psychologist studying language is to explain this fact—to describe the abilities that underlie this infinity of possible performances and state precisely how these abilities, together with the various details . of a given situation, determine any particular performance.” There is no hesi tation here about the psycholinguist’s core business: it is to explain our abilities to produce and to understand language. Indeed, the chapter’s purpose was to review the available research findings on these abilities and it contains, correspondingly, a section on the listener and another section on the speaker. This balance was quickly lost in the further history of psycholinguistics. With the happy and important exceptions of speech error and speech pausing research, the study of language use was factually reduced to studying language understanding. For example, Philip Johnson-Laird opened his review of experimental psycholinguistics in the 1974 Annual Review of Psychology with the statement: “The fundamental problem of psycholinguistics is simple to formulate: what happens if we understand sentences?” And he added, “Most of the other problems would be half way solved if only we had the answer to this question.” One major other 242 W. -

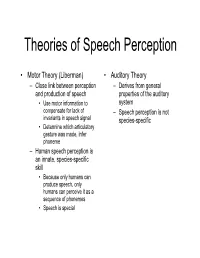

Theories of Speech Perception

Theories of Speech Perception • Motor Theory (Liberman) • Auditory Theory – Close link between perception – Derives from general and production of speech properties of the auditory • Use motor information to system compensate for lack of – Speech perception is not invariants in speech signal species-specific • Determine which articulatory gesture was made, infer phoneme – Human speech perception is an innate, species-specific skill • Because only humans can produce speech, only humans can perceive it as a sequence of phonemes • Speech is special Wilson & friends, 2004 • Perception • Production • /pa/ • /pa/ •/gi/ •/gi/ •Bell • Tap alternate thumbs • Burst of white noise Wilson et al., 2004 • Black areas are premotor and primary motor cortex activated when subjects produced the syllables • White arrows indicate central sulcus • Orange represents areas activated by listening to speech • Extensive activation in superior temporal gyrus • Activation in motor areas involved in speech production (!) Wilson and colleagues, 2004 Is categorical perception innate? Manipulate VOT, Monitor Sucking 4-month-old infants: Eimas et al. (1971) 20 ms 20 ms 0 ms (Different Sides) (Same Side) (Control) Is categorical perception species specific? • Chinchillas exhibit categorical perception as well Chinchilla experiment (Kuhl & Miller experiment) “ba…ba…ba…ba…”“pa…pa…pa…pa…” • Train on end-point “ba” (good), “pa” (bad) • Test on intermediate stimuli • Results: – Chinchillas switched over from staying to running at about the same location as the English b/p -

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism I. MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION A. MUSCLES OF INHALATION (muscles that enlarge the thoracic cavity) 1. Diaphragm Attachments: The diaphragm originates in a number of places: the lower tip of the sternum; the first 3 or 4 lumbar vertebrae and the lower borders and inner surfaces of the cartilages of ribs 7 - 12. All fibers insert into a central tendon (aponeurosis of the diaphragm). Function: Contraction of the diaphragm draws the central tendon down and forward, which enlarges the thoracic cavity vertically. It can also elevate to some extent the lower ribs. The diaphragm separates the thoracic and the abdominal cavities. 2. External Intercostals Attachments: The external intercostals run from the lip on the lower border of each rib inferiorly and medially to the upper border of the rib immediately below. Function: These muscles may have several functions. They serve to strengthen the thoracic wall so that it doesn't bulge between the ribs. They provide a checking action to counteract relaxation pressure. Because of the direction of attachment of their fibers, the external intercostals can raise the thoracic cage for inhalation. 3. Pectoralis Major Attachments: This muscle attaches on the anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle, the sternum and costal cartilages 1-6 or 7. All fibers come together and insert at the greater tubercle of the humerus. Function: Pectoralis major is primarily an abductor of the arm. It can, however, serve as a supplemental (or compensatory) muscle of inhalation, raising the rib cage and sternum. (In other words, breathing by raising and lowering the arms!) It is mentioned here chiefly because it is encountered in the dissection. -

Illustrating the Production of the International Phonetic Alphabet

INTERSPEECH 2016 September 8–12, 2016, San Francisco, USA Illustrating the Production of the International Phonetic Alphabet Sounds using Fast Real-Time Magnetic Resonance Imaging Asterios Toutios1, Sajan Goud Lingala1, Colin Vaz1, Jangwon Kim1, John Esling2, Patricia Keating3, Matthew Gordon4, Dani Byrd1, Louis Goldstein1, Krishna Nayak1, Shrikanth Narayanan1 1University of Southern California 2University of Victoria 3University of California, Los Angeles 4University of California, Santa Barbara ftoutios,[email protected] Abstract earlier rtMRI data, such as those in the publicly released USC- TIMIT [5] and USC-EMO-MRI [6] databases. Recent advances in real-time magnetic resonance imaging This paper presents a new rtMRI resource that showcases (rtMRI) of the upper airway for acquiring speech production these technological advances by illustrating the production of a data provide unparalleled views of the dynamics of a speaker’s comprehensive set of speech sounds present across the world’s vocal tract at very high frame rates (83 frames per second and languages, i.e. not restricted to English, encoded as conso- even higher). This paper introduces an effort to collect and nant and vowel symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet make available on-line rtMRI data corresponding to a large sub- (IPA), which was devised by the International Phonetic Asso- set of the sounds of the world’s languages as encoded in the ciation as a standardized representation of the sounds of spo- International Phonetic Alphabet, with supplementary English ken language [7]. These symbols are meant to represent unique words and phonetically-balanced texts, produced by four promi- speech sounds, and do not correspond to the orthography of any nent phoneticians, using the latest rtMRI technology. -

Articulatory Phonetics

Articulatory Phonetics Lecturer: Dr Anna Sfakianaki HY578 Digital Speech Signal Processing Spring Term 2016-17 CSD University of Crete What is Phonetics? n Phonetics is a branch of Linguistics that systematically studies the sounds of human speech. 1. How speech sounds are produced Production (Articulation) 2. How speech sounds are transmitted Acoustics 3. How speech sounds are received Perception It is an interdisciplinary subject, theoretical as much as experimental. Why do speech engineers need phonetics? n An engineer working on speech signal processing usually ignores the linguistic background of the speech he/she analyzes. (Olaszy, 2005) ¡ How was the utterance planned in the speaker’s brain? ¡ How was it produced by the speaker’s articulation organs? ¡ What sort of contextual influences did it receive? ¡ How will the listener decode the message? Phonetics in Speech Engineering Combined knowledge of articulatory gestures and acoustic properties of speech sounds Categorization of speech sounds Segmentation Speech Database Annotation Algorithms Speech Recognition Speech Synthesis Phonetics in Speech Engineering Speech • diagnosis Disorders • treatment Pronunciation • L2 Teaching Tools • Foreign languages Speech • Hearing aids Intelligibility Enhancement • Other tools A week with a phonetician… n Tuesday n Thursday Articulatory Phonetics Acoustic Phonetics ¡ Speech production ¡ Formants ¡ Sound waves ¡ Fundamental Frequency ¡ Places and manners of articulation ¡ Acoustics of Vowels n Consonants & Vowels n Articulatory vs Acoustic charts ¡ Waveforms of consonants - VOT ¡ Acoustics of Consonants n Formant Transitions ¡ Suprasegmentals n Friday More Acoustic Phonetics… ¡ Interpreting spectrograms ¡ The guessing game… ¡ Individual Differences Peter Ladefoged Home Page: n Professor UCLA (1962-1991) http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/ladefoge/ n Travelled in Europe, Africa, India, China, Australia, etc. -

21 Chapter I Language Production 1.1 Introduction in This Chapter It Will Be

Chapter I Language production 1.1 Introduction In this chapter it will be seen that both models of L1 production as well as accounts of L2 production can shed light on what happens with L2 performance. In particular, this chapter will aim to provide an answer to the following four questions: i) How is language produced? ii) How does L2 production differ from L1 production? iii) How do attention and memory mediate L2 production and development? iv) How can engaging in production potentially lead to second language development? In order to understand how L2 production works we first need to understand how L1 operates, and so L1 production will be considered in the first part of this chapter. Levelt’s (1989) L1 production model will be used as the main reference. Special emphasis will be placed on the areas of message generation, retrieval of lexical items, message formulation, and self-monitoring, with only a more limited consideration of articulation and speech comprehension. In the second part of the chapter, from a number of accounts of L2 production, those aspects that distinguish 21 it from L1 production will be pointed out, and lexical access, grammatical encoding, and self-monitoring will receive special attention. After that, the underlying constructs of attention and memory will be discussed. Regarding attention, the ideas of limited resources, selection, and capacity will be outlined, and the aspects most directly related to production will be underlined. The architecture and processes of memory will be presented, and the distinction between working memory (WM) and long-term memory (LTM) will be established. -

Dynamics of Phonatory Posturing at Phonation Onset

The Laryngoscope VC 2015 The American Laryngological, Rhinological and Otological Society, Inc. Dynamics of Phonatory Posturing at Phonation Onset Travis L. Shiba, MD; Dinesh K. Chhetri, MD Introduction: In speech and singing, the intrinsic laryngeal muscles set the prephonatory posture prior to the onset of phonation. The timing and shape of the prephonatory glottal posture can directly affect the resulting phonation type. We investigated the dynamics of human laryngeal phonatory posturing. Methods: Onset of vocal fold adduction to phonation was observed in 27 normal subjects using high-speed video recording. Subjects were asked to utter a variety of phonation types (modal, breathy, pressed, /i/ following sniff). Digital vid- eokymography with concurrent acoustic signal was analyzed to assess the timing of the following: onset of adduction to final phonatory posture (FPT), phonation onset time (POT), and phonatory posture time (PPT). Final phonatory posture time was determined as the moment at which the laryngeal configuration used in phonation was first achieved. Results: Thirty-three audiovisual recordings met inclusion criteria. Average FPT, PPT, and POT were as follows: 303, 106, and 409 ms for modal; 430, 104, and 534 ms for breathy; 483, 213, and 696 ms for pressed; and 278, 98, and 376 ms for sniff-/i/. The following posturing features were observed: 1) pressed phonation: increased speed of closure just prior to final posture, complete glottal closure, and increased supraglottic hyperactivity; and 2) breathy phonation: decreased speed of closure prior to final posture, increased posterior glottal gap, and increased midmembranous gap. Conclusions: Phonation onset latency was shortest for modal and longest for pressed voice. -

Speech Production

24.963 Linguistic Phonetics Speech Production Reproduced from Srikanth, Byrd and Kaun. (1999) "Geometry, kinematics, and acoustics of tamil liquid consonants." The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, with the permission of the Acoustical Society of America. Hillenbrand et al (1995) 2 Speech Production • Speaking is a very complex motor task, involving the coordination of many articulators. © Source Unknown. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license For more information, see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/. 3 © Joe Perkell. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license For more information, see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/. Slide from Joe Perkel 4 Speech Production - basic questions • So one of the central questions is ‘What are the control parameters in speech production?’ – muscle tensions? – lengths and shortening velocities of muscles? – vocal tract shape? – acoustic/perceptual properties? – all of the above? • Timing/coordination: Speaking involves coordinating movements in time. – How are the control parameters varied over time? – How are changes in control parameters coordinated? 5 A simple model of speech production: the ‘beads on a string’ model • Idea: Speech production involves concatenating a temporal sequence of targets corresponding to phonological segments. • Targets are vocal tract shapes. • Speech production involves concatenating a sequence of vocal tract shapes in time, and coordinating the muscles to move between these shapes. • We see that this model is too simple when we consider data on coarticulatory variation in the realization of segments. 6 Coarticulation • The influence of segmental context on the articulatory/ acoustic realization of a target segment. -

Arabic and English Consonants: a Phonetic and Phonological Investigation

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 6; December 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Arabic and English Consonants: A Phonetic and Phonological Investigation Mohammed Shariq College of Science and Arts, Methnab, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.146 Received: 18/07/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.146 Accepted: 15/09/2015 Abstract This paper is an attempt to investigate the actual pronunciation of the consonants of Arabic and English with the help of phonetic and phonological tools like manner of the articulation, point of articulation, and their distribution at different positions in Arabic and English words. A phonetic and phonological analysis of the consonants of Arabic and English can be useful in overcoming the hindrances that confront the Arab EFL learners. The larger aim is to bring about pedagogical changes that can go a long way in improving pronunciation and ensuring the occurrence of desirable learning outcomes. Keywords: Phonetics, Phonology, Pronunciation, Arabic Consonants, English Consonants, Manner of articulation, Point of articulation 1. Introduction Cannorn (1967) and Ekundare (1993) define phonetics as sounds which is the basis of human speech as an acoustic phenomenon. It has a source of vibration somewhere in the vocal apparatus. According to Varshney (1995), Phonetics is the scientific study of the production, transmission and reception of speech sounds. It studies the medium of spoken language. On the other hand, Phonology concerns itself with the evolution, analysis, arrangement and description of the phonemes or meaningful sounds of a language (Ramamurthi, 2004). -

Prosody in the Production and Processing of L2 Spoken Language and Implications for Assessment

Teachers College, Columbia University Working Papers in TESOL & Applied Linguistics, 2014, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 1-20 Prosody in the Production and Processing of L2 Spoken Language and Implications for Assessment Prosody in the Production and Processing of L2 Spoken Language and Implications for Assessment Christos Theodoropulos1 Teachers College, Columbia University ABSTRACT This article offers an extended definition of prosody by examining the role of prosody in the production and comprehension of L2 spoken language from mainly a cognitive, interactionalist perspective. It reviews theoretical and empirical L1 and L2 research that have examined and explored the relationships between prosodic forms and their functions at the pragmatic and discourse levels. Finally, the importance and the various dimensions of these relationships in the context of L2 assessment are presented and the implications for L2 testing employing new technologies and automated scoring systems are discussed. INTRODUCTION More than two and a half decades ago, Major (1987), in one of the few articles in Language Testing to focus solely on the assessment of speaking in terms of phonological control, wrote that the "measurement of pronunciation accuracy [was] in the dark ages when compared to measurement of other areas of competence" (p. 155). Recognizing the potentially facilitative role of computer-assisted sound-analysis applications and software—a then relatively new industry— Major called for more investigative efforts into objective, reliable, valid, and viable measurements of second language (L2) pronunciation. Since then, only a relatively few noteworthy investigations have answered his call (e.g., Buck, 1989; Gorsuch, 2001; Isaacs, 2008; Koren, 1995; van Weeren & Theunissen, 1987; Yoshida, 2004).