Speech Production, Psychology Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pg. 5 CHAPTER-2: MECHANISM of SPEECH PRODUCTION AND

Acoustic Analysis for Comparison and Identification of Normal and Disguised Speech of Individuals CHAPTER-2: MECHANISM OF SPEECH PRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1. Anatomy of speech production Speech is the vocal aspect of communication made by human beings. Human beings are able to express their ideas, feelings and emotions to the listener through speech generated using vocal articulators (NIDCD, June 2010). Development of speech is a constant process and requires a lot of practice. Communication is a string of events which allows the speaker to express their feelings and emotions and the listener to understand them. Speech communication is considered as a thought that is transformed into language for expression. Phil Rose & James R Robertson (2002) mentioned that voices of individuals are complex in nature. They aid in providing vital information related to sex, emotional state or age of the speaker. Although evidence from DNA always remains headlines, DNA can‟t talk. It can‟t be recorded planning, carrying out or confessing to a crime. It can‟t be so apparently directly incriminating. Perhaps, it is these features that contribute to interest and importance of forensic speaker identification. Speech signal is a multidimensional acoustic wave (as seen in figure 2.1.) which provides information about the words or message being spoken, speaker identity, language spoken, physical and mental health, race, age, sex, education level, religious orientation and background of an individual (Schetelig T. & Rabenstein R., May 1998). pg. 5 Acoustic Analysis for Comparison and Identification of Normal and Disguised Speech of Individuals Figure 2.1.: Representation of properties of sound wave (Courtesy "Waves". -

Phonological Use of the Larynx: a Tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière

Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière To cite this version: Jacqueline Vaissière. Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial. Larynx 97, 1994, Marseille, France. pp.115-126. halshs-00703584 HAL Id: halshs-00703584 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00703584 Submitted on 3 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Vaissière, J., (1997), "Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial", Larynx 97, Marseille, 115-126. PHONOLOGICAL USE OF THE LARYNX J. Vaissière UPRESA-CNRS 1027, Institut de Phonétique, Paris, France larynx used as a carrier of paralinguistic information . RÉSUMÉ THE PRIMARY FUNCTION OF THE LARYNX Cette communication concerne le rôle du IS PROTECTIVE larynx dans l'acte de communication. Toutes As stated by Sapir, 1923, les langues du monde utilisent des physiologically, "speech is an overlaid configurations caractéristiques du larynx, aux function, or to be more precise, a group of niveaux segmental, lexical, et supralexical. Nous présentons d'abord l'utilisation des différents types de phonation pour distinguer entre les consonnes et les voyelles dans les overlaid functions. It gets what service it can langues du monde, et également du larynx out of organs and functions, nervous and comme lieu d'articulation des glottales, et la muscular, that come into being and are production des éjectives et des implosives. -

Speech Error Expressions in Maliki National Debate Tournament (Mandate) 2015

SPEECH ERROR EXPRESSIONS IN MALIKI NATIONAL DEBATE TOURNAMENT (MANDATE) 2015 THESIS By: MUHAMMAD RYDZKY MUHAMMAD ALI NIM 12320079 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES THE ISLAMIC STATE UNIVERSITY MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2017 SPEECH ERROR EXPRESSIONS IN MALIKI NATIONAL DEBATE TOURNAMENT (MANDATE) 2015 THESIS Presented to Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University of Malang in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S) By: MUHAMMAD RYDZKY MUHAMMAD ALI NIM 12320079 Advisor Dr. ROHMANI NUR INDAH, M.Pd. NIP 19760910 200312 2 003 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES THE ISLAMIC STATE UNIVERSITY MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2017 i ii iv v MOTTO قَا َل َر ِّب ا ْش َر ْح لِي َص ْد ِري )52( َويَ ِّس ْر لِي أَ ْم ِري )52( َوا ْحلُ ْل ُع ْق َدةً ِم ْن لِ َسانِي )52( يَ ْفقَهُوا قَ ْولِي )52 Musa said, "Allah, expand for me my breast [with assurance], and ease for me my task, and untie the knot from my tongue, that they may understand my speech. (QS. Thoha: 25-28) vi DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to: My beloved father and mother, Muhammad Ali Hamzah and Abida Yakob Saman. I hope that it could make them proud. It is also for my beloved brother Fitrianto Muhammad Ali and Muhammad Ali Family who always support me. Thank you for my wife, Dian Purwitasari, for helping me finishing this work. vii ACKNOWLEDGMENT All praises are to Allah, who has given power, inspiration, and health in finishing the thesis. All my hopes and wishes are only for him. -

Accuracy in the Detection of Deception As a Function of Training in the Study of Human Behavior

University of Central Florida STARS Retrospective Theses and Dissertations 1976 Accuracy in the Detection of Deception as a Function of Training in the Study of Human Behavior Charner Powell Leone University of Central Florida Part of the Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/rtd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Leone, Charner Powell, "Accuracy in the Detection of Deception as a Function of Training in the Study of Human Behavior" (1976). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 230. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/rtd/230 ACCURACY IN THE DETECTION OF DECEPTION AS A FUNCTION OF TRAINING I N· ·T"H E STU 0 Y 0 F HUMAN BE HA V I 0 R BY CHARNER POWELL LEONE B.S.J., University of Florida, 1967 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts: Communication in the Graduate Studies Program of the College of Social Sciences Florida Technological University Orlando, Florida 1976 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . i v INTRODUCTION . 1 METHODOLOGY . 12 Subjects . 12 Procedure and Materials . 12 RESULTS . 1 7 DISCUSSION . ~ 26 SUMMARY . 34 APPENDIX A. Questionnaire . 37 APPENDIX 8 • Judge•s Scoresheets . 39 REFERENCES . 44 i i LIST OF TABLES TABLE Page 1 Mean Behaviors Used to Discriminate Lying from Truthful Role Players by Decoder Groups . -

Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research the Dynamics of Wordplay

Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research The Dynamics of Wordplay Edited by Esme Winter-Froemel Editorial Board Salvatore Attardo, Dirk Delabastita, Dirk Geeraerts, Raymond W. Gibbs, Alain Rabatel, Monika Schmitz-Emans and Deirdre Wilson Volume 6 Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research Edited by Esme Winter-Froemel and Verena Thaler The conference “The Dynamics of Wordplay / La dynamique du jeu de mots – Interdisciplinary perspectives / perspectives interdisciplinaires” (Universität Trier, 29 September – 1st October 2016) and the publication of the present volume were funded by the German Research Founda- tion (DFG) and the University of Trier. Le colloque « The Dynamics of Wordplay / La dynamique du jeu de mots – Interdisciplinary perspectives / perspectives interdisciplinaires » (Universität Trier, 29 septembre – 1er octobre 2016) et la publication de ce volume ont été financés par la Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) et l’Université de Trèves. ISBN 978-3-11-058634-3 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-058637-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063087-9 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2018955240 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Esme Winter-Froemel and Verena Thaler, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Contents Esme Winter-Froemel, Verena Thaler and Alex Demeulenaere The dynamics of wordplay and wordplay research 1 I New perspectives on the dynamics of wordplay Raymond W. -

1 to “Err” Is Human: the Nature of Phonological “Errors” in Language

To “Err” is Human: The Nature of Phonological “Errors” in Language Development1 Suzanne N. Landi Bryn Mawr College Abstract In children, two types of phonological “errors” may occur: slips of the tongue and pathological speech. A slip of the tongue is considered a normal, non- systematic “error”, whereas a series of consistent speech “errors” is labeled as a speech pathology. Both types of “errors” follow phonotactic constraints defined by the target grammar, and may result in substitutions and omissions of sounds in conversation. They differ traditionally in two key ways: (1) while slips are unique utterances that generally occur only once, the disfluencies are consistent in a pathology, and (2) the speaker is able to notice and correct their error when they make a slip, but it is not the case in a speech pathology. Relevant research to both types of “errors” will be presented for comparison purposes, and theoretical explanations will be offered. I will propose that a deficit in self-monitoring exists in those with disordered phonology, in order to explain why “errors” repeat. 1 I would like to acknowledge my thesis advisor Jason Kandybowicz for his patience and support, as well as Donna Jo Napoli, Jessica Webster-Love and Katie Bates for their valuable comments during this process. Although their contributions were utilized, the following ideas are my own and cannot be blamed on anyone else. I would also like to thank my friends and family for their love and support this semester, including (but not limited to): Deborah Landi, Sue Henry, Jenny Brindisi, Sarah Deibler, Katie Nagrotsky, Skye Rhodes-Robinson, Aaron Schwager and Chuck Bradley. -

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech David Supp-Montgomerie A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Christian Lundberg V. William Balthrop Carole Blair Lawrence Grossberg William Keith © 2013 David Supp-Montgomerie ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT David Supp-Montgomerie: Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech (Under the direction of Christian Lundberg) This dissertation is a critique of the idea that the artifice of public speech is a problem to be solved. This idea is shown to entail the privilege attributed to purportedly direct or unmediated speech in U.S. public culture. I propose that we attend to the ēthos producing effects of rhetorical concealment by asserting that all public speech is constituted through rhetorical artifice. Wherever an alternative to rhetoric is offered, one finds a rhetoric of non-rhetoric at work. A primary strategy in such rhetoric is the performance of sincerity. In this dissertation, I analyze the function of sincerity in contexts of public deliberation. I seek to show how claims to sincerity are strategic, demonstrate how claims that a speaker employs artifice have been employed to imply a lack of sincerity, and disabuse communication, rhetoric, and deliberative theory of the notion that sincere expression occurs without technology. In Chapter Two I begin with the original problem of artifice for rhetoric in classical Athens in the writings of Plato and Isocrates. -

Relations Between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations

14 Relations between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations Willem J. M. Levelt One Agent, Two Modalities There is a famous book that never appeared: Bever and Weksel (shelved). It contained chapters by several young Turks in the budding new psycho- linguistics community of the mid-1960s. Jacques Mehler’s chapter (coau- thored with Harris Savin) was entitled “Language Users.” A normal language user “is capable of producing and understanding an infinite number of sentences that he has never heard before. The central problem for the psychologist studying language is to explain this fact—to describe the abilities that underlie this infinity of possible performances and state precisely how these abilities, together with the various details . of a given situation, determine any particular performance.” There is no hesi tation here about the psycholinguist’s core business: it is to explain our abilities to produce and to understand language. Indeed, the chapter’s purpose was to review the available research findings on these abilities and it contains, correspondingly, a section on the listener and another section on the speaker. This balance was quickly lost in the further history of psycholinguistics. With the happy and important exceptions of speech error and speech pausing research, the study of language use was factually reduced to studying language understanding. For example, Philip Johnson-Laird opened his review of experimental psycholinguistics in the 1974 Annual Review of Psychology with the statement: “The fundamental problem of psycholinguistics is simple to formulate: what happens if we understand sentences?” And he added, “Most of the other problems would be half way solved if only we had the answer to this question.” One major other 242 W. -

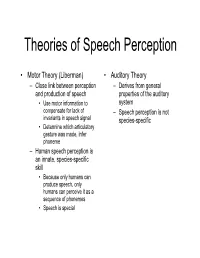

Theories of Speech Perception

Theories of Speech Perception • Motor Theory (Liberman) • Auditory Theory – Close link between perception – Derives from general and production of speech properties of the auditory • Use motor information to system compensate for lack of – Speech perception is not invariants in speech signal species-specific • Determine which articulatory gesture was made, infer phoneme – Human speech perception is an innate, species-specific skill • Because only humans can produce speech, only humans can perceive it as a sequence of phonemes • Speech is special Wilson & friends, 2004 • Perception • Production • /pa/ • /pa/ •/gi/ •/gi/ •Bell • Tap alternate thumbs • Burst of white noise Wilson et al., 2004 • Black areas are premotor and primary motor cortex activated when subjects produced the syllables • White arrows indicate central sulcus • Orange represents areas activated by listening to speech • Extensive activation in superior temporal gyrus • Activation in motor areas involved in speech production (!) Wilson and colleagues, 2004 Is categorical perception innate? Manipulate VOT, Monitor Sucking 4-month-old infants: Eimas et al. (1971) 20 ms 20 ms 0 ms (Different Sides) (Same Side) (Control) Is categorical perception species specific? • Chinchillas exhibit categorical perception as well Chinchilla experiment (Kuhl & Miller experiment) “ba…ba…ba…ba…”“pa…pa…pa…pa…” • Train on end-point “ba” (good), “pa” (bad) • Test on intermediate stimuli • Results: – Chinchillas switched over from staying to running at about the same location as the English b/p -

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism I. MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION A. MUSCLES OF INHALATION (muscles that enlarge the thoracic cavity) 1. Diaphragm Attachments: The diaphragm originates in a number of places: the lower tip of the sternum; the first 3 or 4 lumbar vertebrae and the lower borders and inner surfaces of the cartilages of ribs 7 - 12. All fibers insert into a central tendon (aponeurosis of the diaphragm). Function: Contraction of the diaphragm draws the central tendon down and forward, which enlarges the thoracic cavity vertically. It can also elevate to some extent the lower ribs. The diaphragm separates the thoracic and the abdominal cavities. 2. External Intercostals Attachments: The external intercostals run from the lip on the lower border of each rib inferiorly and medially to the upper border of the rib immediately below. Function: These muscles may have several functions. They serve to strengthen the thoracic wall so that it doesn't bulge between the ribs. They provide a checking action to counteract relaxation pressure. Because of the direction of attachment of their fibers, the external intercostals can raise the thoracic cage for inhalation. 3. Pectoralis Major Attachments: This muscle attaches on the anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle, the sternum and costal cartilages 1-6 or 7. All fibers come together and insert at the greater tubercle of the humerus. Function: Pectoralis major is primarily an abductor of the arm. It can, however, serve as a supplemental (or compensatory) muscle of inhalation, raising the rib cage and sternum. (In other words, breathing by raising and lowering the arms!) It is mentioned here chiefly because it is encountered in the dissection. -

Phonological Encoding in Adults Who Clutter and Adults Who Stutter Phd

Phonological Encoding in Adults Who Clutter and Adults Who Stutter PhD School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences Jess Bretherton-Furness August 2016 Acknowledgements Thanks to David Ward for encouraging me to undertake this project and for being so supportive throughout its completion. Also thanks to Douglas Saddy for his support and ideas especially when creating my stimuli. Special thanks to Bobby Stuijfzand and Dr Kou Murayama for helping me work out how to analyse my data, to Becky Lucas for her time and patience and to Suzannah, Tiffany, Birthe and Faith for cake, positivity and being the best office buddies a girl could ask for. Declaration I confirm that this is my own work and the use of all material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. The work presented in chapter six has been published. Bretherton-Furness, J., Ward, D., & Saddy, D. (2016). Creating a non-word list to match 226 of the Snodgrass standardised picture set. i Table of Contents 1 CHAPTER ONE .......................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1.1 Definitions ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Epidemiology of stuttering and cluttering ...................................................................... 3 1.1.3 Causes of Stuttering and Cluttering ............................................................................... -

Illustrating the Production of the International Phonetic Alphabet

INTERSPEECH 2016 September 8–12, 2016, San Francisco, USA Illustrating the Production of the International Phonetic Alphabet Sounds using Fast Real-Time Magnetic Resonance Imaging Asterios Toutios1, Sajan Goud Lingala1, Colin Vaz1, Jangwon Kim1, John Esling2, Patricia Keating3, Matthew Gordon4, Dani Byrd1, Louis Goldstein1, Krishna Nayak1, Shrikanth Narayanan1 1University of Southern California 2University of Victoria 3University of California, Los Angeles 4University of California, Santa Barbara ftoutios,[email protected] Abstract earlier rtMRI data, such as those in the publicly released USC- TIMIT [5] and USC-EMO-MRI [6] databases. Recent advances in real-time magnetic resonance imaging This paper presents a new rtMRI resource that showcases (rtMRI) of the upper airway for acquiring speech production these technological advances by illustrating the production of a data provide unparalleled views of the dynamics of a speaker’s comprehensive set of speech sounds present across the world’s vocal tract at very high frame rates (83 frames per second and languages, i.e. not restricted to English, encoded as conso- even higher). This paper introduces an effort to collect and nant and vowel symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet make available on-line rtMRI data corresponding to a large sub- (IPA), which was devised by the International Phonetic Asso- set of the sounds of the world’s languages as encoded in the ciation as a standardized representation of the sounds of spo- International Phonetic Alphabet, with supplementary English ken language [7]. These symbols are meant to represent unique words and phonetically-balanced texts, produced by four promi- speech sounds, and do not correspond to the orthography of any nent phoneticians, using the latest rtMRI technology.