Channeling Anger and Hate for Protecting Human Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

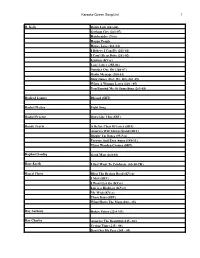

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Hate That I Love You-Rihanna Lyrics & Chords

Music resources from www.traditionalmusic.co.uk For personal educational purposes only Hate That I Love You-Rihanna lyrics & chords Hate That I Love You-Rihanna C D G Cadd9 x 2 C D G Cadd9 Thats how much I love you C D G Cadd9 Thats how much I need you C D G Cadd9 C And I cant stand ya must everything you do make me wanna smile D G C C D Can I not like it for awhile No.. but you wont let me G Cadd9 C You upset me girl, then you kiss my lips D C D All of a sudden I forget that I was upset Cant remember what you did C D G Cadd9 Well I hate it You know exactly what to do C9 D G Cadd9 So that I cant stay mad at you For too long, thats wrong C D G Cadd9 Girl, I hate it You know exactly how to touch C D Cadd9 So that I dont wanna fuss and fight no more C D So I despise that I adore you C D G Cadd9 And I hate how much I love you boy C D G Cadd9 I cant stand how much I need you G D G Cadd9 And I hate how much I love you boy C D Am But I just cant let you go C D G And I hate that I love you so.. G Cadd9 C And you completely know the power that you have D G The only one that makes me laugh C D G Cadd9 C Sad and its not fair how you take advantage of the fact that I D Cadd9 C D Love you beyond the reason why and it just aint right And I hate how much I love you girl I cant stand how much I need you And I hate how much I love you girl But I just cant let you go and I hate that I love you so Em C D Em One of these days maybe your magic wont affect me D And your kiss wont make me weak A7 C D But no one in this world knows me the way you know me Em -

Kappale Artisti

14.7.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Selˆe The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderˆnger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Can't Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The W England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Re˜ections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

Central Times

Central Times Staff Clair B.• Gillian B.• Beau F.• Filip F.• Jamie H.• Ellis J. Emily K.• Sara L.• Sydney L.• Sidney L.• Zoe M.• Tom M. Jeremy N.• Sam O. • Noah Q.• Sam R.• Makaila R.• Owen S. Jack S.• Natalie S. Faculty Advisor: Mrs. Dalleska Volume 4 No. 7 New Babies at Central By Zoe M. Sari and Mrs. Novak Recently, a few teachers at Central School have become new parents. I interviewed two of them: Ms. Novak, and Ms. Dalleska. Q: What is your child’s name? Ms. Novak: Sarah Faith Ms. Dalleska: Madison Sophia Q: Why did you choose that name for your child? Ms. Novak: Sarah is the name of Mr. Novak’s grandmother, and Faith is the name of mine. Ms. Dalleska: It’s a very strong name, but it is still pretty. Q: How does it feel to be a mother? Ms. Novak: I don’t think it’s real yet: I keep waiting for Sarah’s mom to come pick her up. Ms. Dalleska: It’s really exciting, and feels like a huge important job, as well as a present. Q: How has your life changed at all since you had your baby, and why? Ms. Novak: Now I worry all the time about Sarah, I’m afraid she’ll hurt herself or something. Ms. Dalleska: I try to be as perfect as I can because I feel like her role model. Q: How has your child changed? Ms. Novak: Sarah makes facial expressions, stays awake for longer, and has a stronger immune system. -

Come & Get It<Span Class="Orangetitle"> Deconstructed

Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com Come & Get It Deconstructed Skip to: Audio/Video At a Glance Song Overview Structural Analysis Momentum/Tension/Intensity (MTI) Lyrics & Harmonic Progression The Music The Vocal Melody Primary Instrumentation, Tone & Mix Compositional Assessment Hit Factor Assessment Conclusion Why it’s a Hit Songwriter/Producer Take Aways Audio/Video Back to Top At a Glance Back to Top Artist: Selena Gomez Song/Album: Come & Get It / Stars Dance Songwriters: Dean, Eriksen, Hermansen Genre: Pop Sub Genre: Electropop, World (Indian) Length: 3:52 Structure: B-A-B-A-B-C-B Tempo: 80 bpm First Chorus: 0:15 / 6% into the song Intro Length: 0:15 Outro Length: n/a Electric vs. Acoustic: Electric Primary Instrumentation: Synth Lyrical Theme: Love/Relationships Title Occurrences: Come & Get It occurs 12 times within the song Primary Lyrical P.O.V: 1st & 2nd Song Overview Back to Top Released as the lead single from her first solo album, Stars Dance, Come & Get It finds Selena Gomez teaming up with 3 of today’s hottest hitmakers including Tor Hermansen & Mikkel Eriksen (both of Stargate), and Ester Dean with the aim of separating her from her Disney 1 / 71 Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com past and to establish her as a major force within the mainstream Pop scene alongside contemporaries including Rihanna, Katy and Britney. As you’ll see within the report, Come & Get It possesses many of the “hit qualities” that are indicative of today’s chart-topping songs, but it also falls short in some key areas that preclude it from realizing its fullest potential. -

Riaa Gold & Platinum Awards

6/1/2015 — 6/30/2015 In June 2015, RIAA certified 126 Digital Single Awards and 6 Album Awards. Complete lists of all album, single and video awards dating all the way back to 1958 can be accessed at riaa.com. RIAA GOLD & JUNE 2015 PLATINUM AWARDS DIGITAL MULTI-PLATINUM SINGLE (53) Cert Date Title Artist Label Plat Level Rel. Date 6/19/2015 ALL I DO IS WIN (FEAT. T-PAIN, DJ KHALED E1 ENTERTAINMENT 3 2/9/2010 LUDACRIS, SNOOP DOGG & RICK ROSS 6/12/2015 RAP GOD EMINEM SHADY/AFTERMATH/ 2 10/15/2013 INTERSCOPE 6/12/2015 RAP GOD EMINEM SHADY/AFTERMATH/ 3 10/15/2013 INTERSCOPE 6/11/2015 GDFR FLO RIDA ATLANTIC RECORDS 2 10/21/2014 6/15/2015 DOG DAYS ARE OVER FLORENCE AND UNIVERSAL RECORDS 3 10/20/2009 THE MACHINE 6/15/2015 DOG DAYS ARE OVER FLORENCE AND UNIVERSAL RECORDS 4 10/20/2009 THE MACHINE 6/17/2015 ROUND HERE FLORIDA GEORGIA REPUBLIC NASHVILLE 2 12/4/2012 LINE 6/15/2015 PROBLEM GRANDE, ARIANA REPUBLIC RECORDS 6 4/28/2014 6/15/2015 PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS KID CUDI UNIVERSAL RECORDS 2 9/15/2009 (NIGHTMARE) 6/15/2015 PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS KID CUDI UNIVERSAL RECORDS 3 9/15/2009 (NIGHTMARE) 6/2/2015 ADORN MIGUEL RCA RECORDS 2 7/31/2012 6/30/2015 ONLY GIRL (IN THE WORLD) RIHANNA DEF JAM 5 10/13/2010 6/30/2015 DISTURBIA RIHANNA DEF JAM 5 6/17/2008 6/30/2015 DIAMONDS RIHANNA DEF JAM 5 11/16/2012 6/30/2015 POUR IT UP RIHANNA DEF JAM 2 11/19/2012 6/30/2015 WHAT’S MY NAME RIHANNA DEF JAM 4 11/16/2010 www.riaa.com GoldandPlatinum @RIAA @riaa_awards JUNE 2015 DIGITAL MULTI-PLATINUM SINGLE (53) continued.. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

Brown Sugar Repertoire – Updated May 2021

REPERTOIRE No Song Title Artist Name Ballad or Dancing Select 1 Dance Wit Me 112 Dancing 2 Only You (Remix) 112 Dancing 3 Boogie Oogie A Taste Of Honey Dancing 4 Make Me Whole Amel Lerrieux Ballad 5 What’s Come Over Me Amel Lerriex & Glenn Lewis Ballad 6 Let’s Stay Together Al Green Ballad or Dancing 7 Fallin' Alicia Keys Ballad 8 If I Ain’t Got You Alicia Keys Ballad 9 No One Alicia Keys Ballad 10 You Don’t Know My Name Alicia Keys Ballad 11 How Come You Don’t Call Me Alicia Keys Ballad 12 I Swear All 4 One Ballad 13 Consider Me Allen Stone Ballad 14 Taste Of You Allen Stone Dancing 15 Make It Better Anderson .Paak Ballad 16 Leave The Door Open Anderson .Paak | Bruno Mars Ballad 17 Valerie Amy Winehouse Dancing 18 Best Of Me Anthony Hamilton Ballad 19 You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman Aretha Franklin Ballad 20 Respect Aretha Franklin Dancing 21 I Say A Little Prayer Aretha Franklin Ballad 22 Until You Come Back to Me Aretha Franklin Ballad 23 Rock Steady Aretha Franklin Dancing 24 Side To Side Ariana Grande Dancing 25 People Everyday Arrested Development Dancing 26 Foolish Ashanti Ballad 27 Nothing On You B.O.B & Bruno Mars Dancing 28 Change The World Babyface Ballad 29 Whip Appeal Babyface Ballad 30 Every time I Close My Eyes Babyface Ballad 31 Can’t Get Enough Of Your Love Baby Barry White Dancing 32 How Deep Is Your Love Bee Gees Ballad 33 Poison Bel Biv Devoe Dancing 34 Love on Top Beyoncé Dancing 35 Déjà vu Beyoncé Dancing 36 Work It Out Beyoncé Dancing 37 Crazy In Love Beyoncé Dancing 38 Halo Beyoncé Ballad 39 Irreplaceable -

Karaoke Queen Song List 1 R. Kelly Down

Karaoke Queen Song List 1 R. Kelly Down Low (261-06) Gotham City (261-07) Hairbraider (76-6) Happy People Honey Love (261-04) I Believe I Can Fly (261-01) I Can't Sleep Baby (261-02) Ignition (KVer) Love Letter (255-03) Number One Hit (260-07) Radio Message (260-01) Slow Dance (Hey Mr. DJ) (261-05) When A Woman Loves (240 - 05) You Remind Me Of Something (261-03) Rachael Lampa Blessed (SBT) Rachel Platten Fight Song Rachel Proctor Days Like This (SBT) Randy Travis A Better Class Of Loser (SBT) America Will Always Stand (SBT) Diggin' Up Bones (99-NA) Forever And Ever Amen (149-11) Three Wooden Crosses (SBT) Raphael Saadiq Good Man (260-03) Rare Earth I Just Want To Celebrate (62-10 CK) Rascal Flatts Bless The Broken Road (KVer) I Melt (SBT) I Won't Let Go (KVer) Life is a Highway (KVer) My Wish (KVer) These Days (SBT) What Hurts The Most (284 - 15) Ray Anthony Hokey Pokey (22-4 VP) Ray Charles America The Beautiful (245 - 04) Crying Time (245 - 08) Don't Set Me Free (245 - 09) Karaoke Queen Song List 2 Ray Charles (con't) Drown In My Own Tears (245 - 10) Georgia On My Mind (245 - 02) Hallelujah I Love Her So (245 - 13) I Believe To My Soul (245 - 12) Hit The Road, Jack (19-13 LUP) I Can't Stop Loving You (245 - 03) I Gotta Woman (245 - 07) It Had To Be You (245 - 14) Let's Go Get Stoned (245 - 15) Mess Around (245 - 16) Nighttime Is The Right Time (245 - 11) Shake A Tail Feather (245 - 17) Song For You, A (245 - 18) Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word (245 - 22) Unchain My Heart (245 - 01) What'd I Say - Charles, Ray (245 - 05) Yesterday -

Artist Song Album Blue Collar Down to the Line Four Wheel Drive

Artist Song Album (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Blue Collar Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Down To The Line Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Four Wheel Drive Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Free Wheelin' Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Gimme Your Money Please Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Hey You Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Lookin' Out For #1 Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Roll On Down The Highway Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Take It Like A Man Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Hits of 1974 (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Hits of 1974 (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. Blue Sky Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Rockaria Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Showdown Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Strange Magic Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Sweet Talkin' Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Telephone Line Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Turn To Stone Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr.