Domestication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goldfish Morphology As a Model for Evolutionary Developmental Biology

Overview Goldfish morphology as a model for evolutionary developmental biology Kinya G. Ota* and Gembu Abe Morphological variation of the goldfish is known to have been established by artificial selection for ornamental purposes during the domestication process. Chinese texts that date to the Song dynasty contain descriptions of goldfish breeding for ornamental purposes, indicating that the practice originated over one thousand years ago. Such a well-documented goldfish breeding process, combined with the phylogenetic and embryological proximities of this species with zebrafish, would appear to make the morphologically diverse goldfish strains suitable models for evolutionary developmental (evodevo) studies. How- ever, few modern evodevo studies of goldfish have been conducted. In this review, we provide an overview of the historical background of goldfish breed- ing, and the differences between this teleost and zebrafish from an evolutionary perspective. We also summarize recent progress in the field of molecular devel- opmental genetics, with a particular focus on the twin-tail goldfish morphology. Furthermore, we discuss unanswered questions relating to the evolution of the genome, developmental robustness, and morphologies in the goldfish lineage, with the goal of blazing a path toward an evodevo study paradigm using this tel- eost species as a new model species. © 2016 The Authors. WIREs Developmental Biology pub- lished by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. How to cite this article: WIREs Dev Biol 2016, 5:272–295. doi: 10.1002/wdev.224 INTRODUCTION processes of goldfish strains have been documented by authors in many different countries using different fi – he gold sh (Carassius auratus) is a well-known, languages.1 9 Of these reports, the descriptions by Tornamental, domesticated teleost species, which Smartt2 are the most up-to-date and cover the widest consists of a number of morphologically divergent range of the literature. -

First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

"First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources" (SoWAnGR) Country Report of the United Kingdom to the FAO Prepared by the National Consultative Committee appointed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Contents: Executive Summary List of NCC Members 1 Assessing the state of agricultural biodiversity in the farm animal sector in the UK 1.1. Overview of UK agriculture. 1.2. Assessing the state of conservation of farm animal biological diversity. 1.3. Assessing the state of utilisation of farm animal genetic resources. 1.4. Identifying the major features and critical areas of AnGR conservation and utilisation. 1.5. Assessment of Animal Genetic Resources in the UK’s Overseas Territories 2. Analysing the changing demands on national livestock production & their implications for future national policies, strategies & programmes related to AnGR. 2.1. Reviewing past policies, strategies, programmes and management practices (as related to AnGR). 2.2. Analysing future demands and trends. 2.3. Discussion of alternative strategies in the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 2.4. Outlining future national policy, strategy and management plans for the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 3. Reviewing the state of national capacities & assessing future capacity building requirements. 3.1. Assessment of national capacities 4. Identifying national priorities for the conservation and utilisation of AnGR. 4.1. National cross-cutting priorities 4.2. National priorities among animal species, breeds, -

TOP-VIEW GOLDFISH: the OTHER PERSPECTIVE Steve Hopkins

TOP-VIEW GOLDFISH: THE OTHER PERSPECTIVE Steve Hopkins By some accounts, there are over three hundred varieties of goldfish. These can be grouped in various ways such as by tail type, presence or absence of head growth, presence or absence of dorsal fin, eye shape, etc. They can also be grouped based on a whether they were bred and selected to be viewed from the top or viewed from the side. Originally, all goldfish were kept in shallow ponds, ceramic bowls or other containers and viewed from the top. Considering the thousand-year history of goldfish keeping, the glass aquarium is a relatively new innovation which did not come into use until about 150 years ago. However, being able to easily view goldfish from the side through glass has undoubtedly influenced what characteristics are selected for and impacted the development of new varieties. Today, the goldfish hobbyists are a diverse group. While most goldfish are destined for the home aquarium and represent an indoor diversion, goldfish ponds, tubs and goldfish in the water garden continue to increase in popularity. When choosing a goldfish, it is important to consider how it will be viewed and select a variety which is appropriate for the setting in which it will be displayed. In selecting a top-view goldfish, remember that they are typically seen against a dark background. It does not matter what color your tub or pond was when it was new, over time the surfaces will become covered with algae and other growth and appear dark green to black. Without doubt, red and white metallic-scale goldfish provide the contrast to display best against a dark background. -

NUTRAFIN Nr.4-USA 22-03-2004 10:29 Pagina 1

NUTRAFIN Nr.4-USA 22-03-2004 10:29 Pagina 1 Aquatic News 2,50 US$/3,50 Can$/2,50 Euro/2 £/5 Aus$ £/5 2,50 US$/3,50 Can$/2,50 Euro/2 ÉÄw@ÉÄw@ ZZ y|á{xáy|á{xá #4 Issue #4 - 2004 Issue NUTRAFIN Nr.4-USA 22-03-2004 10:29 Pagina 2 DO YOU KNOW THE FACTS OF LIGHT? A strong, vibrant light is essential to the growth and health of your aquarium. This much you probably already know. But did you know that the average fluorescent tube loses LIFE-GLO 2 High-noon spectrum for aquariums, terrariums & vivariums about 50% of its lighting output quality within one year? This results in a distorted spectrum, inefficient plant and coral growth, and less intense fish colors. POWER-GLO Promotes coral, invertebrate and plant growth GLO offers a wide variety of tubes for every aquarium setup. They also provide you with a re- minder sticker to place either directly on the tube AQUA-GLO Intensifies fish colors and promotes plant growth or on the aquarium itself to remind you when it’s time to replace the bulb. FLORA-GLO Optimizes plant growth Or, if you prefer, sign up online at www.hagen.com and we’ll send you a reminder when it’s time. MARINE-GLO Promotes marine reef life So, replace your tubes regularly. You’ll love the results and your fish will love their home. SUN-GLO General purpose aquarium lighting NUTRAFIN Nr.4-USA 22-03-2004 10:29 Pagina 3 Editorial Editorial Dear Reader, "silent as a fish in water", fishes The first three issues of can communicate, often better NUTRAFIN Aquatic News than people.. -

Poultry in the United Kingdom the Genetic Resources of the National Flocks

www.defra.gov.uk Poultry in the United Kingdom The Genetic Resources of the National Flocks November 2010 Cover: Red Dorking male (photograph John Ballard, courtesy of The Cobthorn Trust) All information contained in this brochure was correct at time of going to press (December 2010). Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Nobel House 17 Smith Square London SW1P 3JR Telephone: 020 7238 6000 Website: www.defra.gov.uk © Crown copyright 2010 Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design rests with the Crown. This publication (excluding the logo) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright with the title and source of the publication specified. This document is also available on the Defra website. Published by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Printed in the UK, December 2010, on material that contains a minimum of 100% recycled fibre for uncoated paper and 75% recycled fibre for coated paper. PB13451 December 2010. Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Poultry keeping systems 4 3. Species Accounts 6 3.1. The Domestic Fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus) 6 3.2. Turkeys 8 3.3. Ducks 8 3.4. Geese 9 3.5. Minor Species 9 4. Breed Organisations 10 5. Data Recording and Registration 11 6. References 12 7. Annex: Current situation for individual breeds and strains 13 Abbreviations 24 1 1. Introduction Domestic poultry form the most important sector of livestock keeping worldwide, the production of meat and eggs being a major contributor to human nutrition. -

Goldfish Varieties Poster

m Indu riu str ua ie q s GOLDFISH VARIETIES - (Carassius auratus) A STRAIGHT TAILS Common Goldfish FANTAILS Redcap Fantail PEARLSCALES Most fantail varieties have short globular bodies. Tail and Top of the head deep red, body Have the general characteristics of a fantail with a softer (ALSO KNOWN AS SINGLE TAILS) Body not as long or slender more globular body and characteristic, raised, convex as that of a comet, tail fin is other fins paired except for dorsal fin, which is single. and fins pure white. ECCTTOORRSS EEDDIITTI Common goldfish, comets and shubunkins have relatively (domed) scales. CCOOLLLLE IOONN long slender bodies. Tail fin is single. relatively short. Veiltail Pearlscale Ryukin Body short and globular. Tail fin As described above. Comet Fantail Body short and deep (a depth ¾ double, very broad, with straight-cut Redcap Comet (Tancho trailing edges. Length 1 to 1.5 times Body long and slender, tail fin is As described above. or more than body length) with Comet in Japan) body length. To date this variety has long and well spread. characteristic hump contour on the Top of the head, deep red, body back. The magnitude of the hump not been produced commercially. and fins pure white. increases as the fish matures. Tail is approximately half the length of the body length. Ping Pong Pearlscale Calico The name Ping Pong is used Mirrorscale Comet where the pearlscale’s body shape Scales mainly transparent Tail fin is long and well spread. Shubunkin is extremely round. with many colours same as A row of prominent large scales Scales mainly transparent. -

British Poultry Standards

British Poultry Standards Complete specifi cations and judging points of all standardized breeds and varieties of poultry as compiled by the specialist Breed Clubs and recognised by the Poultry Club of Great Britain Sixth Edition Edited by Victoria Roberts BVSc MRCVS Honorary Veterinary Surgeon to the Poultry Club of Great Britain Council Member, Poultry Club of Great Britain This edition fi rst published 2008 © 2008 Poultry Club of Great Britain Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing programme has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered offi ce John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial offi ce 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, United Kingdom For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of the author to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. -

National Goldfish Standards & Technical Information

NATIONAL GOLDFISHSTANDARDS & TECHNICAL INFORMATION BOOKLET No: 4 EleventhEdition 2002 FederatioDof British Aquatic Societies '[i{milbnri Eir'ni^tp{(hrFid FOREWORD This is the eleventh repdnt and tlle third revision of the Federation's Goldish Standards.Fist pdflted in 1947they were unique in that many ol the feau.res tust appea.ringin the standads hav€ been adopted by other orglnjsatioDs both at home and thorEhout the world. The five hverty pointing system being but one ofthem. Th€ 1947st ndaralswerc subject to a major revision in 1954to recogllisethe advancementsthat had beenmade in gold6sh breeding. In 1973 when the last revision took place some adjustnents werc made to exrstingstandards, but pinaily the rcvision was to introduce rcw standardsto cater for severalnew vadetiesthat werebeins imporledftom the Far fast in quandry Somer\ /mry yearslatrer we ari aware of yet firther variation in some of the standards,most notable the fi$age of be Bistol Sh"bunkin, the Tancho CMet ^ d. Tatcho Orunda afld tbe eye sacsof the Subble-eft. To enableB to recogniseand cater for these alterations the Federation's Judges & Si:ndards Committee have lmdertakena major ovemll ofthe Goldfsh Shndards. The conunittee has sought opinion iom goldfsh keepels both within the Federahonaid odemally to il and whilst not claiming to have accepteda1i of the views put forward l'e have r]sed those, which we consideredwere best suited to our requirements,thjs has resultedin some modifcation of both some dfawings ard texl with a view ofrendedng them morc faciie in use ard to seek their acce?tability to the widest possible spectmm of goidfsh opinion. -

Single Tailed Goldfish Are Very Closely Related to the Common Goldfish, Or Wild Goldfish

How To Take Care Of Goldfish http://www.howtotakecareofgoldfish.com Page 1 How To Take Care Of Goldfish When You Reach The End Of This Book, You Will Know How To Take Care Of Goldfish Easily! Are You Ready? Let's Start! Legal Notice: This e-book is copyright protected. This is only for personal use. You cannot amend, distribute, sell, use, quote or paraphrase any part or the content within this e-book without the consent of the author or copyright owner. http://www.howtotakecareofgoldfish.com Page 2 How To Take Care Of Goldfish Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction All About Goldfish Types of Goldfish How To Select A Goldfish Chapter 2 What Is An Aquarist Selecting an Aquarium How To Setup Your Aquarium Circulation Filtration Lighting Plants – Artificial vs. Living Maintaining Your Aquarium Fishbowls and Tanks Chapter 3 Is A Pond Right For You Types of Ponds Maintaining Your Pond Pond Supplies Conditioning and Treating Water In A Pond Chapter 4 What Do Goldfish Eat Chapter 5 Sick Goldfish and How To Care For Their Illness Common Diseases, Symptoms and Treatments How Can You Tell If Your Goldfish Are Pregnant Caring for Pregnant Goldfish Dying Goldfish and Euthanasia Chapter 6 Goldfish Trivia http://www.howtotakecareofgoldfish.com Page 3 How To Take Care Of Goldfish CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION If you are reading this, then most likely you are one of the many people who love goldfish. You are in good company because goldfish make excellent pets. Actually, goldfish are the most popular domesticated aquatic life in the world. -

RARE POULTRY CLASSES 8 Malay Pullet

ASIAN HARDFEATHER 36 Ko Shamo Black/White/Self Pullet Regional Show 37 Ko Shamo AOC Male Sec: Z Shakeshaft Tel: 07866 575316 38 Ko Shamo AOC Female Judges : Mr R Francis (Large Fowl) 39 Ko Shamo AOC Stag & Mr P Cox ( Bantams) 40 Ko Shamo AOC Pullet 0 41 Asil Male LARGE FOWL 42 Asil Female 43 Tuzo Male 1 Asil Male 44 Tuzo Female 2 Asil Female 45 Non Standard/AOV Male 3 Asil Stag 46 Non Standard/AOV Female 4 Asil Pullet See Juvenile section for entries 5 Malay Male 6 Malay Female 7 Malay Stag RARE POULTRY CLASSES 8 Malay Pullet 9 O Shamo Male (8.8lbs+) RARE POULTRY SOCIETY 10 O Shamo Female (6.6lbs+) Club Show 11 Chu Shamo Male (Under 8.8lbs) Sec: P M Fieldhouse Tel: 01934 12 Chu Shamo Female (under 6.6lbs) 824213 (eve) 13 Shamo Stag (Any size) Judges: Mr J Lockwood 14 Shamo Pullet (Any Size) (Hardfeather & Soft Feather Heavy) 15 Kulang Male Mr P Hayford (True Bantams, 16 Kulang Female Longtails, Juveniles, Pairs & Trios) 17 Satsumadori Male Mr A Hillary (Soft Feather Light 18 Satsumadori Female Breeds 1) 19 Yamato Gunkei Male Mr J Robertson (Soft Feather Light 20 Yamato Gunkei Female Breeds 2) 21 Yamato Gunkei Stag 22 Yamato Gunkei Pullet LONG TAILED LARGE 23 Non Standard/AOV Male 24 Non Standard/AOV Female 47 Yokohama Male See Juvenile section for entries 48 Sumatra Male 49 Yokohama Female BANTAMS 50 Sumatra Female 25 Malay Male LARGE SOFTFEATHER LIGHT 26 Malay Female BREEDS 27 Ko Shamo Black Red Male 28 Ko Shamo Black Red Stag 51 Andalusian Male 29 Ko Shamo Duckwing Male 52 Andalusian Female 30 Ko Shamo Duckwing Stag 53 Ayam Cemani M/F -

Ringing Scheme Ring Sizes

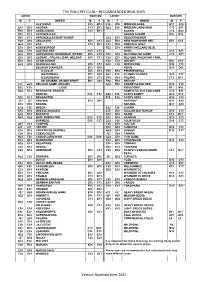

THE POULTRY CLUB – RECOMMENDED RING SIZES LARGE BANTAM LARGE BANTAM M F BREED M F M F BREED M F ALSTEIRER K15 M12 E18 D16 MODERN GAME B11 A10 E18 D16 ANCONA C13 B11 G22 E18 MODERN LANGSHAN C13 B11 E18 K15 ANDALUSIAN C13 B11 NANKIN C13 M12 D16 C13 APPENZELLER NANKIN SHAMO D16 D16 D16 C13 APPENZELLER BARTHUNER G22 E18 NEIDERRHEINER F20 D16 ARAUCANA K15 C13 G22 E18 NEW HAMPSHIRE RED K15 C13 G22 E18 ASIL C13 B11 E18 D16 NORFOLK GREY E18 D16 AUGSBURGER G22 E18 NORTH HOLLAND BLUE G22 E18 AUSTRALORP K15 C13 OHIKI C13 B11 G22 E18 AUTOSEXING: RHODEBAR, WYBAR K15 C13 E18 D16 OLD ENGLISH GAME C13 B11 E18 D16 LEGBAR , CREAM L’BAR, WELBAR K15 C13 F20 E18 OLD ENG. PHEASANT FOWL D16 D16 AYAM CEMANI F20 E18 ORLOFF D16 C13 G22 E18 BARNEVELDER K15 C13 G22 F20 ORPINGTON D16 C13 BELGIAN D’ANVERS B11 A10 PEKIN D16 D16 D’UCCLE D16 C13 F20 E18 PENEDESENCA WATERMAEL B11 A10 G22 E18 PLYMOUTH ROCK K15 C13 D’EVERBURG D16 C13 D16 D16 POLAND C13 B11 DE GRUBBE, DE BOITSFORT B11 A10 F20 E18 REDCAP J27 G22 BELGIAN GAME: BRUGES G22 E18 RHODE ISLAND RED K15 C13 G22 E18 LIĖGE ROSECOMB B11 A10 G22 C13 BERGISCHE KRAHER RUMPLESS OLD ENG GAME C13 B11 BOOTED D16 C13 G22 F20 SCOTS DUMPY D16 C13 D16 C13 BRABANTER F20 E18 SCOTS GREY K15 C13 J27 J27 BRAHMA E18 D16 SEBRIGHT B11 A10 E18 D16 BRAKEL SERAMA B11 A10 G22 F20 BREDA G22 F20 SHAMO E18 D16 BRESSE-GAULOIS E18 D16 SICILIAN BUTTERCUP D16 C13 G22 E18 BUCKEYE E18 D16 SILKIE C13 B11 H24 G22 BUFF ORPINGTON K15 C13 E18 D16 SPANISH K15 C13 BURMESE D16 C13 G22 F20 SULMTALER D16 C13 D16 C13 CAMPINE F20 E18 SULTAN J27 J27 COCHIN E18 -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS