Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

WWW.IRCF.ORG TABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES &IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 27(2):288–292 • AUG 2020 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES . Chasing BullsnakesAmphibians (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: of the Melghat, On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared History of TreeboasMaharashtra, (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: India A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 RESEARCH ARTICLES Hayat A. Qureshi and Gajanan A. Wagh . Biodiversity Research Laboratory,The Texas Horned Department Lizard in of Central Zoology, and ShriWestern Shivaji Texas Science ....................... College, Emily Amravati, Henry, Jason Maharashtra–444603, Brewer, Krista Mougey, India and Gad (gaj [email protected]) 204 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida .............................................Brian J. Camposano,Photographs Kenneth L. Krysko, by the Kevin authors. M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 CONSERVATION ALERT . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................. 220 . More Than Mammals ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

VLE List Hisar District

VLE List Hisar District Block CSC LOCATION VLE_NAME Status Adampur Kishangarh Anil Kumar Working Adampur Khairampur Bajrang Bali Working Adampur Mandi Adampur Devender Duddi not working Adampur Chaudhariwali Vishnu Kumar Working Adampur Bagla Parhlad Singh Working Adampur Chuli Bagrian Durgesh Working Adampur Adampur Gaon Manmohan Singh Working Adampur Sadalpur Mahender Singh Working Adampur Khara Barwala Vinod Kumar Working Adampur Moda Khera Jitender Working Adampur Kabrel Suresh Rao Working Adampur Chuli Kallan Pushpa Rani Working Adampur Ladvi Anil Kumar Working Adampur Chuli Khurd Mahesh Kumar Working Adampur Daroli Bharat Singh Working Adampur Chabarwal Sandeep Kumar Working Adampur Dhani Siswal Sunil Kumar Working Adampur Jawahar Nagar Rachna not working Adampur Asrawan Ramesh Kumar Working Adampur Mahlsara Parmod Kumar Working Adampur Dhani Mohbatpur Sandeep Kumar Working ADAMPUR Mohbatpur Parmod Working ADAMPUR Kajla Ravinder Singh not working Adampur Mothsara Pawan Kumar Working Adampur Siswal Sunil Kumar Working Adampur Gurshal Surender Singh not working Adampur Kohli Indra Devi Working Adampur Telanwali Nawal Kishore Working Agroha Fransi Bhupender Singh Working Agroha Kuleri Hanuman Working Agroha Agroha Suresh Kumar not working Agroha Nangthala Mohit Kathuria Working Agroha Kanoh Govind Singh Working Agroha Kirori Vinod Kumar Working Agroha Shamsukh Pawan Kumar Working Agroha Chikanwas Kuldeep Kumar Working Agroha Siwani Bolan Sanjay Kumar Working Agroha Mirpur Sandeep Kumar Working Agroha Sabarwas Sunil kumar Working Agroha -

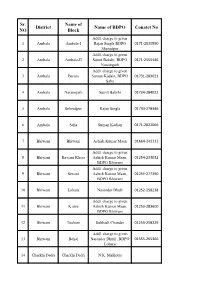

Sr. NO District Name of Block Name of BDPO Conatct No

Sr. Name of District Name of BDPO Conatct No NO Block Addl. charge to given 1 Ambala Ambala-I Rajan Singla BDPO 0171-2530550 Shazadpur Addl. charge to given 2 Ambala Ambala-II Sumit Bakshi, BDPO 0171-2555446 Naraingarh Addl. charge to given 3 Ambala Barara Suman Kadain, BDPO 01731-283021 Saha 4 Ambala Naraingarh Sumit Bakshi 01734-284022 5 Ambala Sehzadpur Rajan Singla 01734-278346 6 Ambala Saha Suman Kadian 0171-2822066 7 Bhiwani Bhiwani Ashish Kumar Maan 01664-242212 Addl. charge to given 8 Bhiwani Bawani Khera Ashish Kumar Maan, 01254-233032 BDPO Bhiwani Addl. charge to given 9 Bhiwani Siwani Ashish Kumar Maan, 01255-277390 BDPO Bhiwani 10 Bhiwani Loharu Narender Dhull 01252-258238 Addl. charge to given 11 Bhiwani K airu Ashish Kumar Maan, 01253-283600 BDPO Bhiwani 12 Bhiwani Tosham Subhash Chander 01253-258229 Addl. charge to given 13 Bhiwani Behal Narender Dhull , BDPO 01555-265366 Loharu 14 Charkhi Dadri Charkhi Dadri N.K. Malhotra Addl. charge to given 15 Charkhi Dadri Bond Narender Singh, BDPO 01252-220071 Charkhi Dadri Addl. charge to given 16 Charkhi Dadri Jhoju Ashok Kumar Chikara, 01250-220053 BDPO Badhra 17 Charkhi Dadri Badhra Jitender Kumar 01252-253295 18 Faridabad Faridabad Pardeep -I (ESM) 0129-4077237 19 Faridabad Ballabgarh Pooja Sharma 0129-2242244 Addl. charge to given 20 Faridabad Tigaon Pardeep-I, BDPO 9991188187/land line not av Faridabad Addl. charge to given 21 Faridabad Prithla Pooja Sharma, BDPO 01275-262386 Ballabgarh 22 Fatehabad Fatehabad Sombir 01667-220018 Addl. charge to given 23 Fatehabad Ratia Ravinder Kumar, BDPO 01697-250052 Bhuna 24 Fatehabad Tohana Narender Singh 01692-230064 Addl. -

OPTION ENERGY PVT LTD. HANSI, Hissar, Haryana

OPTION ENERGY PVT LTD. HANSI, Hissar, Haryana A PRESENTATION ON “Experience in Biogas Upgrading and Bottling at Hansi Plant.” By Abhay Sinha, B.Tech IIT Delhi, MBA Melbourne business School 22-23 August 2013 at IIT Delhi INTRODUCTION • 1000 cubic m/day plant started in Dec 2012. • At Gaushala with about 3000 cattle • Dry cows with about 20 tons of dung/day • Selection of this Gaushala – based on business minded trustees. • Plant on BOO (Build, own and operate) basis. • Land leased by Gaushala for 20 years. • Dung @ Rs 125 per ton. • 10% of revenue from Bio CNG to Gaushala. Technology • Retention Time = 5 days • Continuous Flow (24x7 operation) • 70% methane • Pre-engineered, modular, scalable design • Computerized and automated operation • Low maintenance as few moving parts. • Consistent fibre quality of the organic manure Technology • PSA for purification • 95.8 % methane, (CO2 = 3.8%, O2 = 0.1%, H2S below 2 ppm, N2= 0.3%) • Scrub through water could have been cheaper solution. • Compressed to 150 bars • Filled into cylinders/bottles through manifold. Process Diagram Organic Manure • Organic Manure is also having very fibrous & very rich in “total organic carbon matter (32.7%)” which helps plants in nitrogen fixation and improving the soil - Confirmed by Shriram Institute for Industrial Research. • Farmers of local area are using our bio manure repeatedly in their farms. • Kribhco has agreed to purchase from us Economics • Revenue: Bio CNG = 400-500 kg/day @ Rs 50/kg. • Revenue: Bio-Fertilizer = 5-6 tons/day @ Rs 2- 4 per kg. • A new plant of this size = Rs1.75 Crores • PBP for a new plant = 3 years • First Plant = Rs 3 Crores as lots of learning cost Challenges Faced • A large number of clearance – takes away time, energy, money and kills enthusiasm – not commensurate with the size of the plant. -

The Vakatakas

CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM INDICARUM VOL. V INSCRIPTIONS or THE VAKATAKAS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM INDICARUM VOL. V INSCRIPTIONS OF THE VAKATAKAS EDITED BY Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, M.A., D.Litt* Hony Piofessor of Ancient Indian History & Culture University of Nagpur GOVERNMENT EPIGRAPHIST FOR INDIA OOTACAMUND 1963 Price: Rs. 40-00 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA PLATES PWNTED By THE MRECTOR; LETTERPRESS P WNTED AT THE JQB PREFACE after the of the publication Inscriptions of the Kalachun-Chedi Era (Corpus Inscrip- tionum Vol in I SOON Indicarum, IV) 1955, thought of preparing a corpus of the inscriptions of the Vakatakas for the Vakataka was the most in , dynasty glorious one the ancient history of where I the best Vidarbha, have spent part of my life, and I had already edited or re-edited more than half the its number of records I soon completed the work and was thinking of it getting published, when Shri A Ghosh, Director General of Archaeology, who then happened to be in Nagpur, came to know of it He offered to publish it as Volume V of the Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Series I was veiy glad to avail myself of the offer and submitted to the work the Archaeological Department in 1957 It was soon approved. The order for it was to the Press Ltd on the printing given Job (Private) , Kanpur, 7th 1958 to various July, Owing difficulties, the work of printing went on very slowly I am glad to find that it is now nearing completion the course of this I During work have received help from several persons, for which I have to record here my grateful thanks For the chapter on Architecture, Sculpture and I found Painting G Yazdam's Ajanta very useful I am grateful to the Department of of Archaeology, Government Andhra Pradesh, for permission to reproduce some plates from that work Dr B Ch Chhabra, Joint Director General of Archaeology, went through and my typescript made some important suggestions The Government Epigraphist for India rendered the necessary help in the preparation of the Skeleton Plates Shri V P. -

Abrcs (Aug-2021)

List of Vacancies Offered in Re-Counselling of ABRCs (Aug-2021) SN District BlockName Cluster Name 1 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS MAJRI 2 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS MOHRI BHANOKHERI 3 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS CHHAPRA 4 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS JANSUI 5 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS ISMAILPUR 6 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS NAGGAL 7 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS NANYOLA 8 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS BAKNOUR 9 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS DURANA 10 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS SHAHPUR 11 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS GHEL 12 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS RAMBAGH ROAD,A/CANTT 13 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS BOH 14 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS GARNALA 15 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS RAMPUR SARSHERI 16 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS SULTANPUR 17 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS PANJOKHRA 18 Ambala BARARA GSSS DHANAURA 19 Ambala BARARA GSSS DHEEN 20 Ambala BARARA GSSS TANDWAL 21 Ambala BARARA GSSS UGALA 22 Ambala BARARA GSSS MULLANA 23 Ambala BARARA GSSS THAMBER 24 Ambala BARARA GSSS HOLI 25 Ambala BARARA GSSS ZAFFARPUR 26 Ambala BARARA GSSS RAJOKHERI 27 Ambala BARARA GSSS MANKA-MANKI 28 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS NAGLA RAJPUTANA 29 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS KATHEMAJRA 30 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS DERA 31 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS BHUREWALA 32 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS JEOLI 33 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS LAHA 34 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS BHARERI KALAN 35 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS SHAHPUR NURHAD 36 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS KANJALA 37 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS GADHAULI 38 Ambala SAHA GSSS KESRI 39 Ambala SAHA GSSS SAMLEHRI 40 Ambala SAHA GSSS NAHONI List of Vacancies Offered -

Haryana Vidhan Sabha Debates 26Th July, 1968

Haryana Vidhan Sabha Debates 26 th July, 1968 Vol-1 – No.9 OFFICIAL REPORT CONTENTS Friday, the 26 t h July, 1968 Page Observation made by the Speaker (9)1 Starred Question and Answerers (9) 1 Short Notice Question and Answer (9)21 Demands for Grants (9)22 Extension of the Sitting (9)24 Discussion on Demands for Grants (9)25 Personal Explanation by the Finance Minister (Shrimati Om Prabha Jain) (9)56 Resumption of Discussion for Grants (9)57 Voting on Demands for Grants (9)61-66 ERRATA HARYANA VIDHAN SABHA DEBATES VOL.1 No. 9, DATED 26 TH JULY, 1968 “kqn~/k v”kqn~/k Ik`’BIk`’BIk`’B Ykbu Together Together (9)3 28 fefuLVj befuLVj (9)15 25 eSfMdy eSfMyd (9)20 11 Re.1 Re. (9)22 3 uhps ls ns nsa nsnsa (9)25 18 c<+s cM+s (9)28 8 Add ik uh Dk and igys (9)28 23 between V~;wcoSYt V~;woSYt (9) 28 24 tYnh tUnh (9)28 7 Add ds egdesa and (9) 29 9 between cgwr ek;wlh ek;lh (9) 29 igyh uhps ls ljdkj ljdj (9)30 3 lkeuk lkekuk (9)31 24 ljdkj ljdj (9) 34 5 uhps ls iSlk ilk (9)35 8 Ukjokuk fczt Ukjokukct (9)45 22 yxsxk Ik xsxk (9)46 igyh uhps ls czkap czkap (9)48 1 Add gS jgk and fd (9)55 8 between cSM cM (9)56 18 HARYANA VIDHAN SABHA Friday, the 26 th July, 1968 The Vidhan Sabha met in the Hall of the Haryana Vidhan Sabha, Vidhan Bhavan, Chandigarh, at 9-30 A.M. -

Culture on Environment: Rajya Sabha 2013-14

Culture on Environment: Rajya Sabha 2013-14 Q. No. Q. Type Date Ans by Members Title of the Questions Subject Specific Political State Ministry Party Representati ve Nomination of Majuli Shri Birendra Prasad Island as World Heritage Environmental 944 Unstarred 14.08.2013 Culture Baishya Site Conservation AGP Assam Protected monuments in Environmental 945 Unstarred 14.08.2013 Culture Shri D.P. Tripathi Maharashtra Conservation NCP Maharashtra Shri Rajeev Monuments of national Environmental *209 Starred 05.02.2014 Culture Chandrasekhar importance in Karnataka Conservation IND. Karnataka Dr. Chandan Mitra John Marshall guidelines for preservation of Environmental Madhya 1569 Unstarred 05.02.2014 Culture monuments Conservation BJP Pradesh Pollution Shri Birendra Prasad Majuli Island for World Environmental 1572 Unstarred 05.02.2014 Culture Baishya Heritage list Conservation AGP Assam Monuments and heritage Environmental Madhya 2203 Unstarred 12.02.2014 Culture Dr. Najma A. Heptulla sites in M.P. Conservation BJP Pradesh NOMINATION OF MAJULI ISLAND AS WORLD HERITAGE SITE 14th August, 2013 RSQ 944 SHRI BIRENDRA PRASAD BAISHYA Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) the present status of the nomination dossier submitted for inscription of Majuli Island as World Heritage Site; (b) whether Government has fulfilled all requirements for completion of the nomination process in respect of Majuli Island; (c) if so, the details thereof and date-wise response made on all queries of UNESCO; and (d) by when the island is likely to be finally inscribed as a World Heritage Site? MINISTER OF CULTURE (SHRIMATI CHANDRESH KUMARI KATOCH) (a) (b) The revised nomination dossier on Majuli Island submitted to World Heritage Centre (WHC) in January, 2012 needs further modification in view of revision of Operational Guidelines. -

Ecotourism Proposal for Narnala, Wan and Ambabarwa Wild Life

Welcome To Narnala Wild Life Sanctuary Where History and Nature mingle in Harmony Kham Talao: Narnala Wildlife Sanctuary Akot WildLife Division Akot: Maharashtra. Ms Imtienla Ao IFS. Deputy Conservator of Forest. Akot WildLife Division, Akot.Maharashtra. 1 HISTORY OF NARNALA FORT The district gazetteer of Akola describes the Narnala fort in a very lucid manner: An excerpt :- Narnala is an ancient fortress in the hills in the north of Akot, taluka at a point where a narrow tongue of Akola District runs a few miles in to the Melghat. It is uninhabited but is in charge of a patel and patwari; the latter, Narayan Dattatreya, has a fund of information about it. The fortress lies about 12 miles north of Akot, the road passing through Bordi and the deserted village of Shahanur. The latter village lies within the first roll of the hills but just at the foot of the real ascent. Its lands were made forest two years ago and signs of cultivation are rapidly disappearing. It has a bungalow and sarai, through no caretaker, and carts can go only as far as this. The rest of the road is under the care of the District Board but is in parts exceedingly steep and stony; however camels mount it, and it is possible to ride a horse all the way. The road climbs a spur of the hills and then follows a ridge, the whole ascent from Shahanur occupying less than an hour. About half way up it crosses first one and then another piece of level ground, each thickly sprinkled with Mohammedan tombs. -

Field Office(S) Telephone Directory of Public Health Engineering Deptt., Haryana As On: 01/09/2021

Field Office(s) Telephone Directory of Public Health Engineering Deptt., Haryana as on: 30/09/2021 Office Name Person Name Mobile No. Desig. E-Mail Address Tel. No. (O) Tel. No. (R) Ambala Circle Sh. Ashok Sharma 9416553553 SE [email protected] 0171-2601273 01746-235123 Ambala City PHED Sh.Dinesh Gaba 8295707076 EE [email protected] 0171-2521121 Ambala PHED Sh. Anil Kumar 9728286963 EE [email protected] 0171-2601208 Naraingarh PHED Sh. Sameer Sharma 8901267711 EE [email protected] 01734-284095 01734-287681 Panchkula PHED Sh.Vikas Lathar 9416997066 EE [email protected] 01733-253157 Yamuna Nagar PHED No. 1 Sh. Parik Garg 9729265648 EE [email protected] 01732-266050 Yamuna Nagar PHED No. 2 Sh.Sumit Garg 8059530576 EE [email protected] 01732-237826 Ambala Mech. Circle Sh.Nishi Pal 9812998197 SE [email protected] 0171-2601727 Ambala Cantt. (M) PHED Sh.Rajesh Sharma 9466693637 EE [email protected] 0171-2631402 Rewari (GWI) PHED Sh.Rajesh Sharma 9466693637 EE [email protected] 01274-260344 Sonipat Mech. PHED Sh.B.S.Hooda (Add. Charge) 9468483200 EE [email protected] Bhiwani Circle Sh. Jaswant Singh 9466155801 SE [email protected] 01664-242021 Bhiwani PHED No. 1 Sh.Sunil Ranga 9416510884 EE [email protected] 01664-242004 Bhiwani PHED No. 2 Sh. Parmod Kumar 9306500986 EE [email protected] 01664-242002 01276242976 Charkhi Dadri PHED Sh. Dalbir Dalal (Addi. Charge) 9466603272 EE [email protected] 01250-220150 Siwani PHED Sh.Rahul Berwal 9050223303 EE [email protected] 01255-277066 Tosham PHED Sh.Dalbir Dalal 9466603272 EE [email protected] 01253-258774 01250-220846 Gurugram Circle Sh. -

Officewise Postal Addresses of Public Health Engineering Deptt. Haryana

Officewise Postal Addresses of Public Health Engineering Deptt. Haryana Sr. Office Type Office Name Postal Address Email-ID Telephone No No. 1 Head Office Head Office Public Health Engineering Department, Bay No. 13 [email protected] 0172-2561672 -18, Sector 4, Panchkula, 134112, Haryana 2 Circle Ambala Circle 28, Park road, Ambala Cantt [email protected]. 0171-2601273 in 3 Division Ambala PHED 28, PARK ROAD,AMBALA CANTT. [email protected] 0171-2601208 4 Sub-Division Ambala Cantt. PHESD No. 2 28, PARK ROAD AMBALA CANTT. [email protected] 0171-2641062 5 Sub-Division Ambala Cantt. PHESD No. 4 28, PARK ROAD, AMBALA CANTT. [email protected] 0171-2633661 6 Sub-Division Ambala City PHESD No. 1 MODEL TOWN, AMBALA CITY [email protected] 0171-2601208 7 Division Ambala City PHED MODEL TOWN, AMBALA CITY NEAR SHARDA [email protected] 0171-2521121 RANJAN HOSPITAL OPP. PARK 8 Sub-Division Ambala City PHESD No. 3 MODEL TOWN, AMBALA CITY [email protected] 0171-2521121 9 Sub-Division Ambala City PHESD No. 5 MODEL TOWN, AMBALA CITY. [email protected] 0171-2521121 10 Sub-Division Ambala City PHESD No. 6 28, PARK ROAD, AMBALA CANTT. [email protected] 0171-2521121 11 Division Yamuna Nagar PHED No. 1 Executive engineer, Public health engineering [email protected] 01732-266050 division-1, behind Meat and fruit market, Industrial area Yamunanagar. 12 Sub-Division Chhachhrouli PHESD Near Community centre Chhachhrouli. [email protected] 01735276104 13 Sub-Division Jagadhri PHESD No. -

Hissar Hi021 Asstt Director Regional Refository Archives Deptt Hr Hi558 Asstt Employment Officer Hi907 Asstt

DDO ID DDO NAME HI694 A.D.S&W.DEVELOPMENT OFFICER HI588 ACCOUNTS OFFICER CIVIL SURGEON HI550 ACCOUNTS OFFICER HOSPITALITY ORGANISATION HARYANA HI068 ACCOUNTS OFFICER NCC HI447 ADDITIONAL DEPUTY COMMISSIONER , HISAR HI951 ADDL DY. COMMISSIONER & CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER DRDA HISAR HI523 ADDL.DY.COM. CUM DISTT RURAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY HI035 AGRICULTURE OFFICER (STATISTICAL) HI037 AGRICULTURE QUALITY CONTROL LAB.ANALYTICAL CHEMISTQUALITY CONTROL HI041 ASSISTANT AGRICULTURE ENGINEER HISAR HI029 ASSISTANT CANE DEVELOPMENT OFFICER HI503 ASSISTANT DIRECTOR I.S&H-I HI495 ASSISTANT DIRECTOR SAFETY & HEALTH HI807 ASSISTANT DIRECTOR SHEEP & WOOL DEVELOPMENT HISAR HI469 ASSISTANT EMPLOYMENT OFFICER HI470 ASSISTANT EMPLOYMENT OFFICER HI471 ASSISTANT EMPLOYMENT OFFICER HI472 ASSISTANT EMPLOYMENT OFFICER HI474 ASSISTANT EMPLOYMENT OFFICER HI476 ASSISTANT EMPLOYMENT OFFICER HI477 ASSISTANT EMPLOYMENT OFFICER HI950 ASSISTANT EMPLOYMENT OFFICR HANSI (HISAR) HI556 ASSISTANT GEOLOGIST DEPTT OF MINES & GEOLOGY HI032 ASSISTANT PLANT PROTECTION OFFICER HISAR HI060 ASSISTANT REGISTRAR COOPERATIVE SOCITIES HANSI, HISAR HI061 ASSISTANT REGISTRAR COOPERATIVE SOCITIES, HISAR HI046 ASSISTANT SOIL CONSERVATION OFFICER HISAR HI836 ASSISTANT TREASURY OFFICER HANSI HISAR HI679 ASSITANT DIRECTOR GOVT HATCHERY FARM, HISAR HI710 ASSTT DIRECTOR HATCHERY HISSAR HI021 ASSTT DIRECTOR REGIONAL REFOSITORY ARCHIVES DEPTT HR HI558 ASSTT EMPLOYMENT OFFICER HI907 ASSTT. DIRECTOR(TECH) GOVT. QUALITY MARKING CENTRE FOR ENGG.GOODS HISAR HI062 AUDIT OFFICER COOPERATIVE SOCITIES HISAR HI857