Social Organization: Garo Tribe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Root in Bangladesh

The Newsletter | No.53 | Spring 2010 24 The Focus: ‘Indigenous’ India Taking root in Bangladesh Mymensingh, Chittagong and in particular Dhaka in ever Recently, a Garo friend of mine became increasing numbers. They leave their villages to look for work or to follow higher education (at colleges and universities). Exact a high-profi le adivasi representative. fi gures are not known but during my last visit I understood that ever increasing numbers of young people are leaving for Dhaka or other He’s considered by (non-Garo) donors, big cities, in search of jobs in domestic service, beauty parlours, or the garment industry. Each village that I visited had seen dozens politicians, academics and media to be of its young people leave. Villagers told me amusing stories about these migrants returning to their homes in the villages during an important spokesperson for indigenous Christmas holidays, with their trolley bags and mobile phones, as if they had come straight from Dubai. people(s) and is frequently consulted Only a minority of Garos are citizens of Bangladesh. The large on a variety of ‘indigenous’ issues. When majority live in the Garo Hills in India (and the surrounding plains of Assam). An international border has separated the Bangladeshi I visited Bangladesh last year, my friend Garos from the hill Garos since 1947. Partition resulted in a much stricter division than ever before. Although trans-boundary mobility and his wife asked me to stay with them. has never stopped, Indian and Bangladeshi Garos increasingly developed in diff erent directions. Bangladeshi Garos were more As a result of their generous off er, I gained oriented towards Dhaka, infl uenced by Bengali language and culture, and obviously aff ected by the distinct political developments before unexpected insights into current changes and after the independence war of 1971. -

Performing the Garo Nation? Garo Wangala Dancing Between Faith and Folklore

Erik de Maaker Leiden University Performing the Garo Nation? Garo Wangala Dancing between Faith and Folklore In recent decades, Wangala dancing has gained prominence as an important cultural expression of the Northeast Indian Garo community. In 2008, a Wangala performance was included in the annual Republic Day parade. Pho- tographs of Wangala dancing have come to play an important role on posters circulated by politicians and on calendars produced by organizations that call for greater political assertion of the Garo community. Beyond these relatively new uses, for adherents of the traditional Garo religion, Wangala dancing con- tinues to be linked to the most important post-harvest festival. In exploring how Wangala dancing has developed into a powerful mediatized expression of the Garo community, this article examines how national- and state-level per- formances continue to be linked to village-level celebrations. keywords: Wangala dance—Republic Day parade—authenticity— folklorization—indigeneity Asian Ethnology Volume 72, Number 2 • 2013, 221–239 © Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture he fifty-eighth Republic Day, 26 January 2008, was celebrated under a Tcrisp blue Delhi winter sky. Political and military leaders, as well as a crowd of thousands, cheered as an immaculately performed parade that wanted to display the military might and cultural diversity of the Indian nation passed them by. In India, the Republic Day parade is an annual event, and ever since 1950, it has been held to commemorate and acknowledge the adoption of the Indian constitution. As with any constitution, it defines the relationship between the Indian state and its citizens, and the parade acts as an expression of the power, endurance, and per- petuity of that state. -

Glimpses from the North-East.Pdf

ses imp Gl e North-East m th fro 2009 National Knowledge Commission Glimpses from the North-East National Knowledge Commission 2009 © National Knowledge Commission, 2009 Cover photo credit: Don Bosco Centre for Indigenous Cultures (DBCIC), Shillong, Meghalaya Copy editing, design and printing: New Concept Information Systems Pvt. Ltd. [email protected] Table of Contents Preface v Oral Narratives and Myth - Mamang Dai 1 A Walk through the Sacred Forests of Meghalaya - Desmond Kharmawphlang 9 Ariju: The Traditional Seat of Learning in Ao Society - Monalisa Changkija 16 Meanderings in Assam - Pradip Acharya 25 Manipur: Women’s World? - Tayenjam Bijoykumar Singh 29 Tlawmngaihna: Uniquely Mizo - Margaret Ch. Zama 36 Cultural Spaces: North-East Tradition on Display - Fr. Joseph Puthenpurakal, DBCIC, Shillong 45 Meghalaya’s Underground Treasures - B.D. Kharpran Daly 49 Tripura: A Composite Culture - Saroj Chaudhury 55 Annexure I: Excerpts on the North-East from 11th Five Year Plan 62 Annexure II: About the Authors 74 Preface The north-eastern region of India is a rich tapestry of culture and nature. Breathtaking flora and fauna, heritage drawn from the ages and the presence of a large number of diverse groups makes this place a treasure grove. If culture represents the entire gamut of relationships which human beings share with themselves as well as with nature, the built environment, folk life and artistic activity, the north-east is a ‘cultural and biodiversity hotspot’, whose immense potential is beginning to be recognised. There is need for greater awareness and sensitisation here, especially among the young. In this respect, the National Knowledge Commission believes that the task of connecting with the north-east requires a multi-pronged approach, where socio-economic development must accompany multi-cultural understanding. -

From Rituals to Stage: the Journey of A·Chik Folk Theatre

The NEHU Journal, Vol XI, No. 2, July 2013, pp. 55-72 55 From Rituals to Stage: The Journey of A·chik Folk Theatre BARBARA S ANGMA * Abstract The A·chiks are one of the major tribes of Meghalaya and is basically an oral community. Though the A·chiks are not aware of the concept of theatre, the elements of folk theatre are to be found in their various performances, from rituals to the present day stage plays. The rituals associated with traditional religion of the A·chiks, that is Songsarek comprise sacrifices of animals, libation and chanting of prayers and myths. They also have a rich repository of epic narrations known as Katta Agana and folk songs of various kinds. Dance, comprising ritual dances, warrior dances and community dances form part of rituals and festivals of the A·chik community. Today majority of A·chiks have become Christians and it is seen that theatrical elements have made inroads into Christian devotion in the forms of kirtans , songkristans, etc. In addition to these, folk plays were performed by the community as early as 1937-38. The seasonal plays have allowed themselves to grow and be influenced by the performances of neighbouring states and communities. Today A·chik theatre has arrived in the true sense in the forms of stage-plays like A·chik A·song and Du·kon. Keywords : A·chik, oral performance, dance, kirtan , plays. he A·chiks or the Garos are one of the three major indigenous tribes of Meghalaya. The tribe is distributed in the five districts Tof Garo Hills - North, East, South, West and South West - that lie in the West of the state of Meghalaya, bordering Assam and Bangladesh. -

ANSWERED ON:06.05.2015 SONGS and DANCE PROGRAMMES Wanaga Shri Chintaman Navsha

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEVELOPMENT OF NORTH EASTERN REGION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:6479 ANSWERED ON:06.05.2015 SONGS AND DANCE PROGRAMMES Wanaga Shri Chintaman Navsha Will the Minister of DEVELOPMENT OF NORTH EASTERN REGION be pleased to state: (a) whether North-Eastern States songs and dance festival had been held in New Delhi recently under the North-Eastern Council; (b) if so, the details thereof; (c) whether the tribals from eight States participated in the said cultural events; and (d) if so, the details thereof and if not, the reasons therefor? Answer The Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region (Dr. Jitendra Singh) (a) & (b): Yes, Sir. A cultural festival called 'Songs and Dances of North East' was organized on 11th April, 2015 at the Indira Gandhi Indoor Stadium, New Delhi by the Department of Art and Culture, Government of Meghalaya with financial support of Rs. 2,18,09,718.00 from the North Eastern Council. The festival was inaugurated by the Hon'blePresident of India. The festival showcased the rich cultural ethnicity and dive- rsity of the North East through culturaldances, folk music and folk fusion. (c) & (d): Yes, Sir. Tribals from all the eight North Eastern States had participated in thefestival.Cultural dances perfo- rmed in the festival include Bihu Dance of Assam; Tapu Dance of Arunachal Pradesh; Pung-dhon-dholokchollom, Cheiroljagoi& Thang-ta of Manipur; Cheraw Dance of Mizoram; Sangtam War Dance (Chingtinyichi) of Nagaland; SinghiChham Dance of Sikkim; Hoja- giri Dance of Tripura; and Ka Shad Mastieh (Khasi), Wangala (Garo), Chad Pliang (Jaintia), Biya Chai (Koch) &Krisok (Hajong) Dances of Meghalaya. -

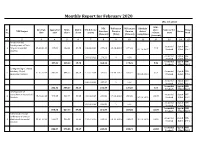

Monthly Report for February 2020 (Rs

Monthly Report for February 2020 (Rs. in Lakhs) State NEC Utilization Utilization Schedule Sl. Sanction Approved NEC's State's NEC Release share Name of the Major NEC Project Sanction Receive Receive date of Sector No. date Cost share share (Date) release State Head (Amount) (Date) (Amount) completion (Amount) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Promotion and Development of Cash Arunachal Agri & MH- 1 Crop in Arunachal 16-12-2014 497.80 448.02 49.78 16-12-2014 179.21 10-02-2016 179.21 9.95 31-12-2017 Pradesh Allied 3601 Pradesh Arunachal Agri & MH- 30-01-2018 179.20 0 0.00 Pradesh Allied 3601 Arunachal Agri & MH- 497.80 448.02 49.78 358.41 179.21 9.95 Pradesh Allied 3601 Strengthening of central hatchery, Nirjuli, Arunachal Agri & MH- 2 17-12-2014 382.41 344.17 38.24 17-12-2014 137.67 01-09-2017 137.67 0.00 Arunachal Pradesh 31-03-2016 Pradesh Allied 3601 Arunachal Agri & MH- 26-04-2018 137.67 0 0.00 Pradesh Allied 3601 Arunachal Agri & MH- 382.41 344.17 38.24 275.34 137.67 0.00 Pradesh Allied 3601 Development of Sericulture in Arunachal Arunachal Agri & MH- 3 05-02-2016 696.75 627.07 69.68 05-02-2016 250.82 09-02-2018 250.82 25.08 Pradesh. 28-02-2019 Pradesh Allied 3601 Arunachal Agri & MH- 22-03-2018 250.82 0 0.00 Pradesh Allied 3601 Arunachal Agri & MH- 696.75 627.07 69.68 501.64 250.82 25.08 Pradesh Allied 3601 Cultivation of Large cardamom in various Arunachal Agri & MH- 4 districts of Arunachal 13-04-2016 662.87 596.58 66.29 13-04-2016 238.63 09-12-2019 238.07 30-04-2019 23.86 Pradesh Allied 3601 Pradesh Arunachal Agri & MH- 662.87 596.58 66.29 238.63 238.07 23.86 Pradesh Allied 3601 State NEC Utilization Utilization Schedule Sl. -

Book CANOPIES and CORRIDORS

Eds: Rahul Kaul, Sandeep Kumar Tiwari, Sunil Kyarong, Ritwick Dutta and Vivek Menon Government of Meghalaya CANOPIES AND CORRIDORS Conserving the forests of Garo Hills with elephants and gibbons as flagships Eds: Rahul Kaul, Sandeep Kumar Tiwari, Sunil Kyarong, Ritwick Dutta and Vivek Menon Garo Hills Autonomous District Council The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) works to improve the welfare of wild and domestic animals through out the world by reducing commercial exploitation of animals, protecting wildlife habitats, and assisting animals in distress. IFAW seeks to motivate the public to prevent cruelty to animals and to promote animal welfare and conservation policies that advance the well-being of both animals and people. Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), is a non-profit conservation organisation, committed to help conserve nature, especially endangered species and threatened habitats, in partnership with communities and governments. Its vision is the natural heritages of India is secure. Suggested Citation: Rahul Kaul, Sandeep Kumar Tiwari, Sunil Kyarong, Ritwick Dutta and Vivek Menon (Eds). Canopies and Corridors- Conserving the forests of Garo Hills with elephants and gibbons as flagships, Wildlife Trust of India. Keywords: Garo Hills, elephant, gibbon, Balapakram National Park, Nokrek National Park, Meghalaya, Siju, Selbalgre, GHADC, Garo Hills Autonomous District Council, sacred groves, forest management. The designations of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the authors or WTI concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Tripura-March-2014.Pdf

Largest bamboo • Tripura accounts for about 55-60 per cent of bamboo sticks required for making incense producing hub in India sticks. Around 21 of the 130 bamboo species known in India are grown in the state. Second largest natural • Tripura is the second largest natural rubber producer in the country, after Kerala. As of rubber producer in India March 2013, 61,231 hectares of area was under natural rubber cultivation. Fifth largest tea • Tripura has 56 tea estates and 4,346 small tea growers, producing 8.43 million kg of tea producing state every year. Tea produced in Tripura is famous for its blending qualities. • A unique harmonious blend of three traditions (tribal, Bengali and Manipuri weaving) can Unique cultural mix in be seen in Tripura’s handicrafts. The state is known for its unique cane and bamboo handicraft art handicrafts. • Tripura has several potential, yet unexplored sectors, such as organic spices, bio-fuel and Untapped resources eco-tourism. It is rich in natural resources such as natural gas, rubber, tea and medicinal provided growth plants. The state is also known for its vibrant food processing, bamboo and sericulture potential industries. Source: Government of Tripura, Aranca Research Offers international • Tripura acts as a gateway between Northeast India and Bangladesh. This offers a trade opportunities potential for international trade. • Tripura’s agro-climatic conditions are favourable for growing various fruit and horticultural crops. The state’s pineapples and oranges are known for their unique flavours and organic Food processing hub in nature. It has set up a modern food park near Agartala to boost growth in the food Northeast processing sector, and an agri-export zone for pineapples. -

The Politics of Difference (Re)Locating Subalternity/Marginality (22-23, September, 2017)

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Assam University (A Central University)- Diphu Campus Diphu, Karbi Anglong, Assam-782462, INDIA CALL FOR PAPERS INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE On tHe pOliticS of dIfferencE (Re)Locating Subalternity/Marginality (22-23, September, 2017) IMPORTANT DATES Last Date of Abstract Submission(250-300 words) 15th August , 2017 Notification of Acceptance of Abstract 2 to 3 days after submission Early Registration 1st July- 15th August,2017 Late Registration 16th August- 10th Sept,2017 Last Date for Submission of Full Paper 10th September, 2017 Conference Dates 22-23, September, 2017 CONCEPT NOTE “Power is everywhere not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere” -Michel Foucault, 1976 The term, ‘politics of difference’ primarily for recognition of their politics and eloquent emerged in the context of identity politics different forms of resistance against out of the experiences of the hegemonic subjects/agencies. The ‘idea of subalternity/marginality in the late 1970s. recognition’ has been influenced by the The social movements such as ethnic, philosophical work of Charles Taylor (1992). women, linguistic, third gender, ecological, In his leading essay, ‘The Politics of peasant, tribal, caste etc, can be constructed Recognition’ argued that how people get through the experiences of those people their identity from being recognized or non- who are instrumental to articulate their recognized as the subject of the politics of differences in terms of politics, action, difference. Thus, the identities can be ideology, recognition and representation shaped by recognition or non-recognition of that led to question the hegemony of the the subjective or objective conditions. agencies. These social movements demand In epistemology, the ‘Politics of Difference’ community, text, agency, gender while refers to the state of ‚subalternity‛ that corroborating or bringing new debates for argue condition of subordination brought understanding the politics of difference. -

4.5 Festivals of North East India

4.5 Festivals of North East India Read about how different festivals are celebrated in the north-eastern States of India. The North east region of India, consisting of seven States, is a place of diverse cultures. The different communities and tribes celebrate their unique festivals with great enthusiasm and joy. Many of their festivals are based on agriculture and no celebration is complete without the traditional music and dance. Blessed with lush greenery and the mighty river Brahmaputra, the people of Assam have a lot to celebrate. So Bihu is the chief festival of this State. It is celebrated by people of all religions, castes or tribes. The three different sets of Bihu mark the beginning of the harvesting season, the completion of sowing and the end of the harvest season. The Bihu dance is a joyous one performed by both young men and women and is noted for is brisk steps and hand movement. Unusual instruments provide traditional music for the dance – the dhol which is similar to a drum, the pepa, a wind instrument made from a buffalo horn, cymbals and a bamboo clapper. The songs have been handed down through many generations. Bihu competitions held all over Assam attract visitors and locals alike in large numbers. Living further north in the mountainous region of the Himalayas, Arunachal Pradesh finds a mention in the ancient literature of the Puranas and the Mahabharata. Nature has provided the people of this region with a deep feeling for beauty which can be seen in their festivities, songs and dances. The new year festival, called Losar is perhaps the most important festival in certain areas of Arunachal. -

IBEF Presentataion

TRIPURA THE LAND OF PERMANENT SPRING For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org November 2017 Table of Content Executive Summary .…………….…………...3 Advantage State ...……………………..…….5 North East Region Vision 2020 ……..….….6 Tripura – An Introduction …………....……....7 Budget ………………………………………..16 Infrastructure Status ...................................17 Business Opportunities ……..…………......30 Doing Business in Tripura …………...….....41 State Acts & Policies ….….………..............45 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY … (1/2) Largest bamboo . Tripura is endowed with rich and diverse bamboo resources. It is home to 21 species of bamboo. The state producing hub in India has an area of 7,195 hectares for the production of bamboo. Strong natural rubber . Tripura is the 2nd largest natural rubber producer in the country, after Kerala. As of 2015-16, production of production base rubber in the state stood at 44,245 tonnes as compared to 39,000 tonnes in 2013-14. Fifth largest tea . Tripura holds a strong tea plantation base, with 58 tea gardens covering an area of over 6,400 hectares as of 2014-15. Due to large availability of land along with appropriate climatic conditions gradual boost to the tea producing state production in the state has been witnessed. In 2015-16, tea production in the state stood at 8.96 million kg. Unique cultural mix in . A unique harmonious blend of 3 traditions (tribal, Bengali & Manipuri weaving) can be seen in Tripura’s handicraft art handicrafts. The state is known for its unique cane & bamboo handicrafts. Untapped resources . Tripura has several potential, yet relatively unexplored sectors such as organic spices, bio-fuel and eco- provided growth tourism. It is rich in natural resources such as natural gas, rubber, tea and medicinal plants. -

Festivals Prevalent in Garo Society: a Discussion 1 Dr

© 2020 JETIR September 2020, Volume 7, Issue 9 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Festivals Prevalent in Garo Society: A Discussion 1 Dr. Himakshi Bordoloi 1 Gauhati University. Abstract Each caste-tribe is rich in its own language, literature and culture. The Garo people, a part of the Mongolian people, rich in their own cultural traditions and heritage, have been living in Northeast India as a prominent tribe since time immemorial. Adjacent to the Garo Hills of Meghalaya, there are a large number of Garo villages in Kamrup and Goalpara districts as well as Sivsagar, Dibrugarh, Darrang and Mikir Pahar districts of Assam. Festivals are an integral part of culture. This research paper discusses some of the most popular festivals in Garo society. Keywords: Festivals, Folk-festival, Garo, Culture. 0.1 Introduction: Each caste-tribe is rich in its own language, literature and culture. The Garo people, a part of the Mongolian people, rich in their own cultural traditions and heritage, have been living in Northeast India as a prominent tribe since time immemorial. Adjacent to the Garo Hills of Meghalaya, there are a large number of Garo villages in Kamrup and Goalpara districts as well as Sivsagar, Dibrugarh, Darrang and Mikir Pahar districts of Assam. Festivals are an integral part of culture. 1.0 Subject-matter Assam has been inhabited by people of different ethnicities, languages and dialects since time immemorial. The people of Assam can be basically divided into tribes and non-tribes. It is very difficult to make a geographical demarcation among the tribes of Assam and bring them under discussion.