Shanghai's Wartime Emergency Money

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download to View

The Mao Era in Objects Money (钱) Helen Wang, The British Museum & Felix Boecking, University of Edinburgh Summary In the early twentieth century, when the Communists gained territory, they set up revolutionary base areas (also known as soviets), and issued new coins and notes, using whatever expertise, supplies and technology were available. Like coins and banknotes all over the world, these played an important role in economic and financial life, and were also instrumental in conveying images of the new political authority. Since 1949, all regular banknotes in the People’s Republic of China have been issued by the People’s Bank of China, and the designs of the notes reflect the concerns of the Communist Party of China. Renminbi – the People’s Money The money of the Mao era was the renminbi. This is still the name of the PRC's currency today - the ‘people’s money’, issued by the People’s Bank of China (renmin yinhang 人民银 行). The ‘people’ (renmin 人民) refers to all the people of China. There are 55 different ethnic groups: the Han (Hanzu 汉族) being the majority, and the 54 others known as ethnic minorities (shaoshu minzu 少数民族). While the term renminbi (人民币) deliberately establishes a contrast with the currency of the preceding Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek, the term yuan (元) for the largest unit of the renminbi (which is divided into yuan, jiao 角, and fen 分) was retained from earlier currencies. Colloquially, the yuan is also known as kuai (块), literally ‘lump’ (of silver), which establishes a continuity with the silver-based currencies which China used formally until 1935 and informally until 1949. -

The History of the Yen Bloc Before the Second World War

@.PPO8PPTJL ࢎҮ 1.ಕ BOZQSJOUJOH QNBD ȇ ȇ Destined to Fail? The History of the Yen Bloc before the Second World War Woosik Moon The formation of yen bloc did not result in the economic and monetary integration of East Asian economies. Rather it led to the increasing disintegration of East Asian economies. Compared to Japan, Asian regions and countries had to suffer from higher inflation. In fact, the farther the countries were away from Japan, the more their central banks had to print the money and the higher their inflations were. Moreover, the income gap between Japan and other Asian countries widened. It means that the regionalization centered on Japanese yen was destined to fail, suggesting that the Co-prosperity Area was nothing but a strategy of regional dominance, not of regional cooperation. The impact was quite long lasting because it still haunts East Asian countries, contributing to the nourishment of their distrust vis-à-vis Japan, and throws a shadow on the recent monetary and financial cooperation movements in East Asia. This experience highlights the importance of responsible actions on the part of leading countries to boost regional solidarity and cohesion for the viability and sustainability of regional monetary system. 1. Introduction There is now a growing literature that argues for closer monetary and financial cooperation in East Asia, reflecting rising economic and political interdependence between countries in the region. If such a cooperation happens, leading countries should assume corresponding responsibilities. For, the viability of the system depends on their responsible actions to boost regional solidarity and cohesion. -

2 | 12 Stamper the Magazine for High-Performance Punching Technology

2 | 12 Stamper The magazine for high-performance punching technology See you at EuroBLECH Innovative solutions BRUDERER precision for China 2012 from KLEINER GmbH BRUDERER will be presenting its newly- The company from Pforzheim in Germany Using a BSTA 1600-117, BBV 450 feed and ARKU peripheral developed BPG 22 planetary gearbox at supplies demanding customers with inno- devices, Shanghai Mint – a subsidiary of the state-run EuroBLECH. This technology enables the vative solutions and products while relying China Bank Note Printing and Minting Corporation (CBPM) high-performance BSTA 510 punching press on stamping technology from BRUDERER’s – stamps blanks for Chinese coins. The BRUDERER punch- to also be used for testing and running in high-performance punching presses. ing press is set up to ensure the ultimate in precision and tools. increased production levels. page 2 page 3 pages 4-5 Issue 02/2012 Issue 02/2012 editorial Looking forward to the euroBLeCH 2012 KLeINER GmBH – thinking in terms of solutions With the stamping world assembling at the Innovation, ultra-modern technologies and highly-motivated expert employees are the recipe for the EuroBLECH in Hanover from 23 – 27 October 2012, healthy growth that KLEINER GmbH company has continually achieved. Part of this success is also down to this will give the BRUDERER stand the opportunity strategic partnerships with customers and suppliers, and since the early 1990s, the Pforzheim-based com- to showcase the new BPG 22 planetary gearbox. pany in Germany has been relying for its stamping technology and toolmaking on Swiss-made BRUDERER The switchable gear can be adjusted by hand punching presses. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham

Victorianizing Guangxu: Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham Scott Relyea, Appalachian State University Abstract In the late Qing and early Republican eras, eastern Tibet (Kham) was a borderland on the cusp of political and economic change. Straddling Sichuan Province and central Tibet, it was coveted by both Chengdu and Lhasa. Informed by an absolutist conception of territorial sovereignty, Sichuan officials sought to exert exclusive authority in Kham by severing its inhabitants from regional and local influence. The resulting efforts to arrest the flow of rupees from British India and the flow of cultural identity entwined with Buddhism from Lhasa were grounded in two misperceptions: that Khampa opposition to Chinese rule was external, fostered solely by local monasteries as conduits of Lhasa’s spiritual authority, and that Sichuan could arrest such influence, the absence of which would legitimize both exclusive authority in Kham and regional assertions of sovereignty. The intersection of these misperceptions with the significance of Buddhism in Khampa identity determined the success of Sichuan’s policies and the focus of this article, the minting and circulation of the first and only Qing coin emblazoned with an image of the emperor. It was a flawed axiom of state and nation builders throughout the world that severing local cultural or spiritual influence was possible—or even necessary—to effect a borderland’s incorporation. Keywords: Sichuan, southwest China, Tibet, currency, Indian rupee, territorial sovereignty, Qing borderlands On December 24, 1904, after an arduous fourteen-week journey along the southern road linking Chengdu with Lhasa, recently appointed assistant amban (Imperial Resident) to Tibet Fengquan reached Batang, a lush green valley at the western edge of Sichuan on the province’s border with central Tibet. -

Full Text (PDF)

Annual Report 2009 Central Bank of the Republic of China (Taiwan) Taipei, Taiwan The Republic of China Foreword Fai-nan Perng, Governor The worldwide recession continued to affect Taiwan's economy during the first half of 2009. During the second half of the year, the turnaround in the U.S. and Europe, coupled with the local government's stimulus package, gradually lifted Taiwan's external trade, private consumption and investment. Economic growth resumed in the fourth quarter but remained at negative 1.87 percent for the year as a whole. The annual unemployment rate also rose to 5.85 percent. Meanwhile, weak domestic demand, on top of falling international commodity prices, led consumer prices to decline by 0.87 percent for the year, a relatively stable level among major countries. To boost domestic demand, the Bank twice lowered policy rates during the first two months of 2009, as part of the rate cut cycle that began in September 2008. A total of 237.5 basis points were slashed on seven occasions during the cycle. Lower interest rates helped reduce the funding costs of individuals and enterprises and encourage private consumption and investment. In addition, the Bank engaged in open market operations to keep reserve money and the interbank call-loan rate at accommodative levels. It also helped enhance the capacity of the Small and Medium Enterprise Credit Guarantee Fund to meet funding demands of SMEs. These measures helped create an environment conducive to economic recovery. Bolstered by monetary easing actions, and net foreign capital inflows in the second half of the year, M2 grew by 7.21 percent in 2009, breaching the upper limit of the Bank's 2.5 percent to 6.5 percent target zone. -

About Beijing

BEIJING Beijing, the capital of China, lies just south of the rim of the Central Asian Steppes and is separated from the Gobi Desert by a green chain of mountains, over which The Great Wall runs. Modern Beijing lies on the site of countless human settlements that date back half a million years. Homo erectus Pekinensis, better known as Peking man was discovered just outside the city in 1929. It is China's second largest city in terms of population and the largest in administrative territory. The name Beijing - or Northern Capital - is a modern term by Chinese standards. It first became a capital in the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), but it experienced its first phase of grandiose city planning in the Yuan Dynasty under the rule of the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, who made the city his winter capital in the late 13th century. Little of it remains in today's Beijing. Most of what the visitor sees today dates from either the Ming or later Qing dynasties. Huge concrete tower blocks have mushroomed and construction sites are everywhere. Bicycles are still the main mode of transportation but taxis, cars, and buses jam the city streets. PASSPORT/VISA CONDITIONS All visitors to Beijing and the People's Republic of China are required to have a valid passport (one that does not expire for at least 6 months after your arrival date in China). A special tourist or business visa is also required. CUSTOMS Travelers are allowed to bring into China one bottle of alcoholic beverages and two cartons of cigarettes. -

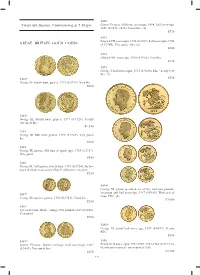

Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

5490 Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm Queen Victoria, old head, sovereign, 1898; half sovereign, 1896 (S.3874, 3878). Good fi ne. (2) $570 5491 Edward VII, sovereigns, 1905 (S.3969); half sovereigns, 1908 GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS (S.3974B). Very good - fi ne. (2) $500 5492 Edward VII, sovereign, 1910 (S.3969). Very fi ne. $370 5493 George V, half sovereigns, 1912 (S.4006). Fine - nearly very fi ne. (2) $350 5482* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1774 (S.3728). Very fi ne. $600 5483* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1777 (S.3728). Nearly extremely fi ne. $1,350 5484 George III, fi fth bust, guinea, 1787 (S.3729). Very good/ fi ne. $500 5485 George III, guinea, fi fth bust of spade type, 1788 (S.3729). Very good. $450 5486 George III, half guinea, fourth bust, 1781 (S.3734). Surface marked (from wear as jewellery?), otherwise very fi ne. $250 5494* George VI, proof specimen set of fi ve and two pounds, sovereign and half sovereign, 1937 (S.PS15). With case of 5487* issue, FDC. (4) George III, quarter guinea, 1762 (S.3741). Good fi ne. $7,000 $250 5488 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, two pounds, 1887 (S.3865). Very good. $700 5495* George VI, proof half sovereign, 1937 (S.4077). Nearly FDC. $850 5489* 5496 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, half sovereign, 1887 Elizabeth II, sovereigns, 1957-1959, 1962-1968 (S.4124, 5). (S.3869). Extremely fi ne. Nearly uncirculated - uncirculated. (10) $250 $3,700 532 5497 Elizabeth II, proof sovereigns, 1979 (S.4204) (2); proof half sovereigns, 1980 (S.4205) (2). -

Annual Report 2020 Central Bank of the Republic of China (Taiwan)

Annual Report 2020 Central Bank of the Republic of China (Taiwan) Taipei, Taiwan Republic of China Foreword Chin-Long Yang, Governor Looking back on 2020, it started with an outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19 that quickly spread out and wreaked havoc on the global economy and world trade. Hampered by the resulting demand weakness both at home and abroad, Taiwan's economic growth slowed to 0.35% in the second quarter, the lowest since the second quarter of 2016. However, the pace picked up further and further in the latter half of the year amid economic reopening overseas and the introduction of consumption stimulus policies domestically. The annual growth rate of GDP reached 5.09% in the fourth quarter, the highest since the second quarter of 2011. For the year as a whole, the economy expanded by 3.11%, also higher than the past two years. Similarly, domestic inflation was affected by the pandemic as softer international demand for raw materials dragged down energy prices and hospitality services (such as travel and hotels) launched promotional price cuts. The annual growth rate of CPI dropped to -0.23%, the lowest since 2016, while that of the core CPI (excluding fruit, vegetables, and energy) fell to 0.35%, a record low unseen for more than a decade. Faced with the unusual challenges posed by pandemic-induced impacts on the economy and the labor market, the Bank reduced the policy rates by 25 basis points and rolled out a special accommodation facility worth NT$200 billion to help SMEs obtain funding in March, followed by an expansion of the facility to NT$300 billion in September. -

The Currency Conversion in Postwar Taiwan: Gold Standard from 1949 to 1950 Shih-Hui Li1

The Kyoto Economic Review 74(2): 191–203 (December 2005) The Currency Conversion in Postwar Taiwan: Gold Standard from 1949 to 1950 Shih-hui Li1 1Graduate School of Economics, Kyoto University. E-mail: [email protected] The discourses on Taiwanese successful currency reform in postwar period usually put emphasis on the actors of the U.S. economic aids. However, the objective of this research is to re-examine Taiwanese currency reform experiences from the vantage- point of the gold standard during 1949–50. When Kuomintang (KMT) government decided to undertake the currency conversion on June 15, 1949, it was unaided. The inflation was so severe that the KMT government must have used all the resources to finish the inflation immediately and to restore the public confidence in new currency as well as in the government itself. Under such circumstances, the KMT government established a full gold standard based on the gold reserve which the KMT government brought from mainland China in 1949. This research would like to investigate what role the gold standard played during the process of the currency conversion. Where this gold reserve was from? And how much the gold reserve possessed by the KMT government during this period of time? Trying to answer these questions, the research investigates three sources of data: achieves of the KMT government in the period of mainland China, the official re- ports of the KMT government in Taiwan, and the statistics gathered from international organizations. Although the success of Taiwanese currency reform was mostly from the help of U.S. -

The Changing Significance of Latin American Silver in the Chinese Economy, 16Th–19Th Centuries

THE CHANGING SIGNIFICANCE OF LATIN AMERICAN SILVER IN THE CHINESE ECONOMY, 16TH–19TH CENTURIES RICHARD VON GLAHN University of Californiaa ABSTRACT The important role of Chinese demand for silver in stimulating world- wide silver-mining and shaping the first truly global trading system has become commonly recognised in the world history scholarship. The com- mercial dynamism of China during the 16th-19th centuries was integrally related to the importation of foreign silver, initially from Japan but princi- pally from Latin America. Yet the significance of imports of Latin American silver for the Chinese economy changed substantially over these three centuries in tandem with the rhythms of China’s domestic economy as well as the global trading system. This article traces these changes, including the adoption of a new standard money of account— the yuan—derived from the Spanish silver peso coin. Keywords: silver, money supply, peso, coinage, international trade JEL Code: N15, N16 RESUMEN El importante papel de la demanda china de plata para estimular la extracción de plata en todo el mundo y dar forma al primer sistema de comercio verdaderamente global se ha reconocido comúnmente por los a University of California, Los Angeles, History. [email protected] Revista de Historia Económica, Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History 553 Vol. 38, No. 3: 553–585. doi:10.1017/S0212610919000193 © Instituto Figuerola, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

CAST COINAGE of the MING REBELS John E. Sandrock

CAST COINAGE OF THE MING REBELS John E. Sandrock Collecting China's ancient coins can be a very worthwhile and rewarding experience. While at first glance this endeavor may appear overwhelming to the average Westerner, it is in reality not difficult once you master a few guidelines and get the hang of it. Essential to a good foundation of knowledge is a clear understanding of the chronology of dynasties, the evolution of the cash coin from ancient to modern times, the Chinese system of dating, the Nien Hao which identifies the coin to emperor and thus to dynasty, and the various forms of writing (calligraphy) used to form the standard characters. Once this basic framework is mastered, almost all Chinese coins fall into one dynastic category or another, facilitating identification and collection. Some do not, however, which brings us to the subject at hand. The coins of the Ming Rebels defy this pattern, as they fall between two dynasties, overlapping both. Thus they do not fit nicely into one category or another and consequently must be treated separately. To put this into historical perspective it is necessary to know that the Ming dynasty lasted from 1368 to the year 1644 and that its successor, the Ch'ing dynasty, existed from 1644 to its overthrow in 1911. Therefore our focus is on the final days of the Ming and beginning of the Ch'ing dynasties. The Ming era was a period of remarkable accomplishment. This was a period when the arts and craftsmanship flourished. Administration and learning soared to new heights.