Resource Pack: Butterworth & Bliss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SMART STRIKE B, 1992

SMART STRIKE b, 1992 height 16.0 Dosage (20-7-17-0-2); DI: 3.38; CD: 0.93 RACE AND (STAKES) RECORD See gray pages—Polynesian Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earned Native Dancer, 1950 Polynesian, by Unbreakable 22s, SW, $785,240 2 0 0 0 0 — Raise a Native, 1961 304 f, 43 SW, 4.06 AEI Geisha, by Discovery 3 4 3 1 0 $51,416 4s, SW, $45,955 4 4 3(2) 0 0 $285,960 838 f, 78 SW, 2.34 AEI Raise You, 1946 Case Ace, by Teddy 24s, SW, $37,220 Totals 8 6(2) 1 0 $337,376 Mr. Prospector, b, 1970 14s, SW, $112,171 14 f, 12 r, 11 w, 2 SW Lady Glory, by American Flag Won Philip H. Iselin H (gr. I, 8.5f), Salvator Mile H 1,178 f, 181 SW, 3.98 AEI Nashua, 1952 Nasrullah, by Nearco (gr. III, 8f). 7.62 AWD 30s, SW, $1,288,565 SIRE LINE Gold Digger, 1962 638 f, 77 SW, 2.37 AEI Segula, by Johnstown 35s, SW, $127,255 SMART STRIKE is by MR. PROSPECTOR, stakes 12 f, 7 r, 7 w, 3 SW Sequence, 1946 Count Fleet, by Reigh Count winner of $112,171, Gravesend H, etc., and sire of 181 17s, SW, $54,850 stakes winners, including champions CONQUISTADOR 8 f, 8 r, 8 w, 3 SW Miss Dogwood, by Bull Dog CIELO (Horse of the Year and champion 3yo colt), Cyane, 1959 Turn-to, by Royal Charger RAVINELLA (in Eur, Eng, and Fr), GULCH, FORTY NINER, 14s, SW, $176,367 ALDEBARAN, RHYTHM, IT’S IN THE AIR, GOLDEN Smarten, 1976 401 f, 47 SW, 2.34 AEI Your Game, by Beau Pere 27s, SW, $716,426 ATTRACTION, EILLO, QUEENA, MACHIAVELLIAN, etc. -

Juddmonte-Stallion-Brochure-2021

06 Celebrating 40 years of Juddmonte by David Walsh 32 Bated Breath 2007 b h Dansili - Tantina (Distant View) The best value sire in Europe by blacktype performers in 2020 36 Expert Eye 2015 b h Acclamation - Exemplify (Dansili) A top-class 2YO and Breeders’ Cup Mile champion 40 Frankel 2008 b h Galileo - Kind (Danehill) The fastest to sire 40 Group winners in history 44 Kingman 2011 b h Invincible Spirit - Zenda (Zamindar) The Classic winning miler siring Classic winning milers 48 Oasis Dream 2000 b h Green Desert - Hope (Dancing Brave) The proven source of Group 1 speed WELCOME his year, the 40th anniversary of the impact of the stallion rosters on the Green racehorses in each generation. But we also Juddmonte, provides an opportunity to Book is similarly vital. It is very much a family know that the future is never exactly the same Treflect on the achievements of Prince affair with our stallions being homebred to as the past. Khalid bin Abdullah and what lies behind his at least two generations and, in the case of enduring and consistent success. Expert Eye and Bated Breath, four generations. Juddmonte has never been shy of change, Homebred stallions have been responsible for balancing the long-term approach, essential Prince Khalid’s interest in racing goes back to over one-third of Juddmonte’s 113 homebred to achieving a settled and balanced breeding the 1950s. He first became an owner in the Gr.1 winners. programme, with the sometimes difficult mid-1970s and, in 1979, won his first Group 1 decisions that need to be made to ensure an victory with Known Fact in the Middle Park Juddmonte’s activities embrace every stage in effective operation, whilst still competing at Stakes at Newmarket and purchased his first the life of a racehorse from birth to training, the highest level. -

6, 2012 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here >ANOTHER= THRILLER in LOUISVILLE the BIRTH of a LEGEND? J

SUNDAY, MAY 6, 2012 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here >ANOTHER= THRILLER IN LOUISVILLE THE BIRTH OF A LEGEND? J. Paul Reddam=s I=ll Have Another (Flower Alley) sat Sent off the 15-8 favorite, Derrick Smith's unbeaten the trip in seventh for most of the way Camelot (GB) (Montjeu {Ire}) duly delivered to provide beneath Mario Gutierrez, and came his late sire with a first mile Classic win after a thrilling streaking down the Churchill Downs finish to yesterday's G1 Qipco 2000 Guineas at stretch to reel in the game-as-can-be Newmarket. Settled pacesetter and 4-1 favorite Bodemeister off the pace racing (Empire Maker) in the 138th GI Kentucky among the group Derby. AI don't know how at this point towards the stand's anything could be bigger than the side, the G1 Racing Kentucky Derby, Reddam responded Horsephotos @ Post Trophy hero when asked to place the win in sliced between rivals perspective with his other accomplishments as an to lead with 150 yards owner. AIf you hear of something, let me know.@ remaining and held off Saturday, Churchill Downs French Fifteen (Fr) KENTUCKY DERBY PRESENTED BY YUM! BRANDS-GI, (Turtle Bowl {Ire}) to $2,219,600, CDX, 5-5, 3yo, 1 1/4m, 2:01 4/5, ft. score by a neck, with 1--I'LL HAVE ANOTHER, 126, c, 3, by Flower Alley Camelot Racing Post/Edward Whitaker another French raider 1st Dam: Arch's Gal Edith, by Arch Hermival (Ire) (Dubawi 2nd Dam: Force Five Gal, by Pleasant Tap {Ire}) 2 1/4 lengths back in third. -

Theories of Infant Development Theories of Infant Development

Theories of Infant Development Theories of Infant Development Edited by Gavin Bremner and Alan Slater © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd except for editorial material and organization © 2004 by Gavin Bremner and Alan Slater 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Gavin Bremner and Alan Slater to be identified as the Authors of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Theories of infant development / edited by Gavin Bremner and Alan Slater. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–631–23337–7 (hc : alk. paper) — ISBN 0–631–23338–5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Infants—Development. 2. Child development. I. Bremner, J. Gavin, 1949– II. Slater, Alan. RJ134.T48 2003 305.232—dc21 2003045328 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10/12 pt Palatino by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall. For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com In memory of George Esmond Butterworth, November 8, 1946–February 12, 2000 Contents Contributors ix Preface xi Part I Development of Perception and Action 1 A Dynamical Systems Perspective on Infant Action and its Development 3 Eugene C. -

WV Graded Music List 2011

2011 WV Graded Music List, p. 1 2011 West Virginia Graded Music List Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade Artist Arranger Title Publisher 1 - Higgins, John Suo Gan HL 1 - McGinty Japanese Folk Trilogy QU 1 - McGinty, Anne Elizabethan Songbook, An KJ 1 - Navarre, Randy Ngiele, Ngiele NMP 1 - Ployhar Along the Western Trail BE 1 - Ployhar Minka BE 1 - Ployhar Volga Boat Song BE 1 - Smith, R.W. Appalachian Overture BE Variant on an Old English 1 - Smith, R.W. BE Carol 1 - Story A Jubilant Carol BE 1 - Story Classic Bits and Pieces BE 1 - Story Patriotic Bits and Pieces BE 1 - Swearingen Three Chorales for Band BE 1 - Sweeney Shenandoah HL 1 Adams Valse Petite SP 1 Akers Berkshire Hills BO 1 Akers Little Classic Suite CF 1 Aleicheim Schaffer Israeli Folk Songs PO 1 Anderson Ford Forgotten Dreams BE 1 Anderson Ford Sandpaper Ballet BE 1 Arcadelt Whiting Ave Maria EM 1 Arensky Powell The Cuckoo PO 1 Bach Gardner Little Bach Suite ST Grand Finale from Cantata 1 Bach Gordon BO #207 1 Bach Walters Celebrated Air RU 1 Bain, James L. M Wagner Brother James' Air BE 1 Balent Bold Adventure WB Drummin' With Reuben And 1 Balent BE Rachel 1 Balent Lonesome Tune WB 1 Balmages Gettysburg FJ 2011 WV Graded Music List, p. 2 1 Balmages Majestica FJ 1 Barnes Ivory Towers of Xanadu SP 1 Bartok Castle Hungarian Folk Suite AL 1 Beethoven Clark Theme From Fifth Symphony HL 1 Beethoven Foulkes Creation's Hymn PO 1 Beethoven Henderson Hymn to Joy PO 1 Beethoven Mitchell Ode To Joy CF 1 Beethoven Sebesky Three Beethoven Miniatures Al 1 Beethoven Tolmage -

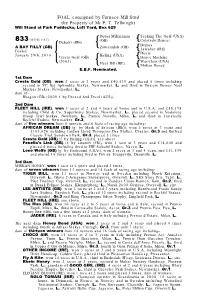

FOAL, the Property of Firebird Stud

FOAL, consigned by Furnace Mill Stud the Property of Mr P. T. Tellwright Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Left Yard, Box 629 Dubai Millennium Seeking The Gold (USA) (WITH VAT) (GB) Colorado Dancer 833 Dubawi (IRE) Deploy Zomaradah (GB) A BAY FILLY (GB) Jawaher (IRE) Foaled Diesis January 29th, 2010 Halling (USA) Cresta Gold (GB) Dance Machine (2003) Warrshan (USA) Fleet Hill (IRE) Mirkan Honey E.B.F. Nominated. 1st Dam Cresta Gold (GB), won 2 races at 3 years and £40,539 and placed 8 times including second in VC Bet Aphrodite Stakes, Newmarket, L. and third in Unicoin Homes Noel Murless Stakes, Newmarket, L.; dam of- Rhagori (GB) (2009 f. by Exceed And Excel (AUS)). 2nd Dam FLEET HILL (IRE), won 3 races at 2 and 4 years at home and in U.S.A. and £48,198 including Child & Co. Superlative Stakes, Newmarket, L., placed second in Vodafone Group Trial Stakes, Newbury, L., Premio Novella, Milan, L. and third in Tattersalls Rockfel Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3; dam of five winners from 6 runners and 6 foals of racing age including- AFRICAN DREAM (GB) (g. by Mark of Esteem (IRE)), won 5 races at 3 years and £103,626 including Jardine Lloyd Thompson Dee Stakes, Chester, Gr.3 and Betfred Classic Trial, Sandown Park, Gr.3, placed 3 times. Cresta Gold (GB) (f. by Halling (USA)), see above. Fenella's Link (GB) (f. by Linamix (FR)), won 1 race at 3 years and £14,000 and placed 4 times including third in EBF Salsabil Stakes, Navan, L. Lone Wolfe (GB) (g. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

COURT VISION Dkb/Br, 2005

COURT VISION dkb/br, 2005 Dosage (11-5-12-0-0); DI: 3.67; CD: 0.96 See gray pages—Polynesian RACE AND (STAKES) RECORD Raise a Native, 1961 Native Dancer, by Polynesian Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earned 4s, SW, $45,955 Mr. Prospector, 1970 838 f, 78 SW, 2.34 AEI Raise You, by Case Ace 2 4 3(2) 1 0 $257,542 14s, SW, $112,171 3 8 2(2) 1(1) 2(2) $748,858 1,178 f, 181 SW, 3.98 AEI Gold Digger, 1962 Nashua, by Nasrullah 35s, SW, $127,255 4 7 1(1) 0 2(2) $591,030 Gulch, b, 1984 32s, SW, $3,095,521 12 f, 7 r, 7 w, 3 SW Sequence, by Count Fleet 5 7 2(2) 2(2) 0 $1,009,091 1,077 f, 75 SW, 1.76 AEI 6 5 1(1) 0 0 $1,140,137 Rambunctious, 1960 Rasper II, by Owen Tudor 7.65 AWD 7s, SW, $101,076 Totals 31 9(8) 4(3) 4(4) $3,746,658 Jameela, 1976 348 f, 14 SW, 1.55 AEI Danae II, by The Solicitor II 58s, SW, $1,038,704 Won At 2 2 f, 2 r, 2 w, 1 SW Asbury Mary, 1969 Seven Corners, by Roman Remsen S (gr. II, $200,000, 9f in 1:52.48, dftg. 13s, wnr, $8,066 Atoned, Trust N Dustan, Big Truck, Springs Road, 7 f, 6 r, 5 w, 1 SW Snow Flyer, by Snow Boots Tide Dancer). Northern Dancer, 1961 Nearctic, by Nearco Iroquois S (gr. -

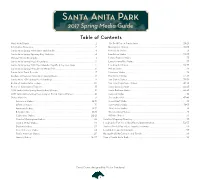

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Symphony Orchestra

School of Music ROMANTIC SMORGASBORD Symphony Orchestra Huw Edwards, conductor Maria Sampen, violin soloist, faculty FRIDAY, OCT. 11, 2013 SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL 7:30 P.M. First Essay for Orchestra, Opus 12 ............................ Samuel Barber (1910–1983) Violin Concerto in D Major, Opus 77 .........................Johannes Brahms Allegro non troppo--cadenza--tranquillo (1833–1897) Maria Sampen, violin INTERMISSION A Shropshire Lad, Rhapsody for Orchestra ..................George Butterworth (1885–1916) Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Opus 43 ............................Jean Sibelius Allegro moderato--Moderato assai--Molto largamente (1865–1957) SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Huw Edwards, conductor VIOLIN I CELLO FRENCH HORN Zachary Hamilton ‘15, Faithlina Chan ’16, Matt Wasson ‘14 concertmaster principal Billy Murphy ‘16 Marissa Kwong ‘15 Bronwyn Hagerty ‘15 Chloe Thornton ‘14 Jonathan Mei ‘16 Will Spengler ‘17 Andy Rodgers ‘16- Emily Brothers ‘14 Kira Weiss ‘17 Larissa Freier ‘17 Anna Schierbeek ‘16 TRUMPET Sophia El-Wakil ‘16 Aiden Meacham ‘14 Gavin Tranter ‘16 Matt Lam ‘16 Alana Roth ‘14 Lucy Banta ‘17 Linnaea Arnett ‘17 Georgia Martin ‘15 Andy Van Heuit ‘17 Abby Scurfield ‘16 Carolynn Hammen ‘16 TROMBONE VIOLIN II BASS Daniel Thorson ‘15 Clara Fuhrman ‘16, Kelton Mock ‘15 Stephen Abeshima ‘16 principal principal Wesley Stedman ‘16 Rachel Lee ‘15 Stephen Schermer, faculty Sophie Diepenheim ‘14 TUBA Brandi Main ‘16 FLUTE and PICCOLO Scott Clabaugh ‘16 Nicolette Andres ‘15 Whitney Reveyrand ‘15 Lauren Griffin ‘17 Morgan Hellyer ‘14 TIMPANI and -

Keith Phares, Baritone, and Michael Baitzer, Piano Department of Music, University of Richmond

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Department Concert Programs Music 3-21-2005 Keith Phares, baritone, and Michael Baitzer, piano Department of Music, University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, University of Richmond, "Keith Phares, baritone, and Michael Baitzer, piano" (2005). Music Department Concert Programs. 342. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs/342 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Concert Programs by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monday, March 21, 2005 • 7:30pm Modlin Center for the Arts Call),p Concert Hall, Booker Hall of Music Keith Phares, baritone Michael Baitzer, piano UN!VER.SlTY OF RICHMOND Sponsored in part by the 175th Anniversary Committee and the University's Cultural Affairs Committee The Modlin Center thanks Style Weekly for media sponsorship of the 2004-2005 season. Tonight's Program La bonne chanson, Op. 61 (Paul Verlaine) Gabriel Faure "Une Sainte en son aureole" (1845-1924) "Puisque l'aube gpndit" "La June blanche luit dans les bois" "J'allais par des chemins perfides" "J'ai presque peur, en verite" "Avant que tune t'en ailles" "Done, ce sera par un clair jour d'ete" "N'est-ce pas?" "L:hiver a cesse" Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen Gustav Mahler "Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht" (1860-1911) "Gieng heut' Morgen tiber's Feld" "Ich hab' ein gltiend Messer" "Die zwei blauen Augen" -Intermission- Bredon Hill and Other Songs (A.E. -

Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 12-2-2014 Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Logan, Cameron, "Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 603. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/603 i Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This study explores the pitch structures of passages within certain works by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax. A methodology that employs the nonatonic collection (set class 9-12) facilitates new insights into the harmonic language of symphonies by these two composers. The nonatonic collection has received only limited attention in studies of neo-Riemannian operations and transformational theory. This study seeks to go further in exploring the nonatonic‟s potential in forming transformational networks, especially those involving familiar types of seventh chords. An analysis of the entirety of Vaughan Williams‟s Fourth Symphony serves as the exemplar for these theories, and reveals that the nonatonic collection acts as a connecting thread between seemingly disparate pitch elements throughout the work. Nonatonicism is also revealed to be a significant structuring element in passages from Vaughan Williams‟s Sixth Symphony and his Sinfonia Antartica. A review of the historical context of the symphony in Great Britain shows that the need to craft a work of intellectual depth, simultaneously original and traditional, weighed heavily on the minds of British symphonists in the early twentieth century.