Performance of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2019 Inform Edition

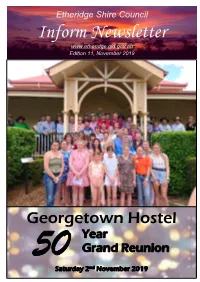

Etheridge Shire Council Inform Newsletter www.etheridge.qld.gov.au Edition 11, November 2019 Georgetown Hostel Year Grand Reunion 50 Saturday 2nd November 2019 MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR Good day to all Mango madness silly season is here once again! I know we are all hanging out for the rain…. It was very exciting to get a few drops the other night. Firstly our sincere condolences go to the family and friends of Bevin Butler (Roaster) who sadly passed away this month. He was a much loved figure around the Shire and will be missed. It has felt like a very long month…. and it’s not over yet with another delegation with the FNQROC in Canberra in the last week of November, lobbying for the sealing of the Savannah Way/ Gulf Development Road, the next stage of the Gilbert River Irrigation area, the Gilbert River Bridge Upgrade along with the Charleston Dam at Forsayth. The month of November has been extremely busy with meetings with Senior Advisors, Ministers, Senators, the Premier and the Deputy Prime Minister regarding the Charleston Dam, Gilbert River Irrigation area, Gilbert River Bridge and the Savannah Way. These meetings have taken place in Cairns, Townsville, Brisbane, Canberra, Hughenden and Mt Isa. The meetings have been very successful. Council were honoured to have Senator James McGrath (Senator for Queensland) and Senator Susan McDonald (Senator for Queensland) visit with us at the dam site - even if briefly. Council presented each with a gift; a piece of the dam wall (granite rock) mounted on a small plinth as a token of appreciation for their efforts in securing funding for the construction of the Dam. -

Identification of Leading Practices in Ensuring Evidence-Based Regulation of Farm Practices That Impact Water Quality Outcomes in the Great Barrier Reef

The Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee Identification of leading practices in ensuring evidence-based regulation of farm practices that impact water quality outcomes in the Great Barrier Reef October 2020 © Commonwealth of Australia ISBN 978-1-76093-122-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. Contents Members ....................................................................................................................................................... v List of Recommendations ........................................................................................................................ vii Chapter 1—Background .............................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2—Governance framework and legislative arrangements ................................................. 15 Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan .................................................................................... 15 Legislation ......................................................................................................................................... 23 Summary of views concerning the Reef regulations package .................................................. -

Mps in Drive for Nuclear Energy - the Australian, 2/18/2021

18/02/2021 MPs in drive for nuclear energy - The Australian, 2/18/2021 MPs in drive for nuclear energy EXCLUSIVE GREG BROWN COALITION’S CLIMATE PUSH Nationals senators have drafted legislation allowing the Clean Energy Finance Corporation to invest in nuclear power as twothirds of Coalition MPs backed lifting the ban on the controversial fuel source to help shift the nation to a carbon- neutral future. The block of five Nationals senators, led by Bridget McKenzie and Matt Canavan, will move an amendment to legislation establishing a $1bn arm at the green bank to allow it to invest in nuclear generators, high-energy, low-emissions (HELE), coal- fired power stations and carbon capture and storage technology. The Nationals’ move comes as a survey of 71 Coalition backbenchers conducted by The Australian revealed that 48 were in favour of lifting the longstanding prohibition on nuclear power in the EPBC act. Liberal MPs Andrew Laming, John Alexander and Gerard Rennick are among backbenchers who want Scott Morrison to take a repeal of the nuclear ban to the upcoming election — a move that would open a new divide with Labor as the nation sets a course for a low-emissions future. “I’m very keen to see the prohibition lifted,” Mr Laming said. “It is something that has to be taken to an election so Australians realise there is a significant change in energy policy.” Mr Alexander said it was like “trying to fight Muhammad Ali with one arm tied behind your back if you are going to ignore nuclear energy”. “This is a new era; let’s be right at the cutting edge,” Mr Alexander said. -

Coalition's Climate Push

AUTHOR: Greg Brown SECTION: GENERAL NEWS ARTICLE TYPE: NEWS ITEM AUDIENCE : 94,448 PAGE: 1 PRINTED SIZE: 493.00cm² REGION: National MARKET: Australia ASR: AUD 12,683 WORDS: 946 ITEM ID: 1400466763 18 FEB, 2021 MPs in drive for nuclear energy The Australian, Australia Page 1 of 3 COALITION’S CLIMATE PUSH MPs in drive for nuclear energy EXCLUSIVE GREG BROWN Nationals senators have drafted legislation allowing the Clean Energy Finance Corporation to invest in nuclear power as two- thirds of Coalition MPs backed lifting the ban on the controver- sial fuel source to help shift the nation to a carbon-neutral future. The block of five Nationals senators, led by Bridget McKen- zie and Matt Canavan, will move an amendment to legislation es- tablishing a $1bn arm at the green bank to allow it to invest in nuclear generators, high-energy, low-emissions (HELE), coal-fired power stations and carbon capture and storage technology. The Nationals’ move comes as a survey of 71 Coalition back- benchers conducted by The Aus- tralian revealed that 48 were in favour of lifting the longstanding prohibition on nuclear power in the EPBC act. Liberal MPs Andrew Laming, John Alexander and Gerard Ren- © News Pty Limited. No redistribution is permitted. This content can only be copied and communicated with a copyright licence. AUTHOR: Greg Brown SECTION: GENERAL NEWS ARTICLE TYPE: NEWS ITEM AUDIENCE : 94,448 PAGE: 1 PRINTED SIZE: 493.00cm² REGION: National MARKET: Australia ASR: AUD 12,683 WORDS: 946 ITEM ID: 1400466763 18 FEB, 2021 MPs in drive for nuclear energy The Australian, Australia Page 2 of 3 nick are among backbenchers this stage”. -

Interim Report on All Aspects of the Conduct of the 2019 Federal Election and Matters Related Thereto

PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Interim report on all aspects of the conduct of the 2019 Federal Election and matters related thereto Delegation to the International Grand Committee, Dublin, Ireland Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters February 2020 CANBERRA © Commonwealth of Australia ISBN 978-1-76092-072-2 (Printed version) ISBN 978-1-76092-073-9 (HTML version) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Contents THE REPORT Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................... v Membership of the Committee .................................................................................................................... vi Terms of reference .......................................................................................................................................... x List of abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... xi List of recommendations ............................................................................................................................. xii 1 Delegation report .............................................................................................. 1 Background to -

Senator Portraits

46th Parliament: Senators Senator the Hon Senator Senator Senator Senator Eric Abetz Alex Antic Wendy Askew Tim Ayres Catryna Bilyk Senator for Tasmania Senator for Senator for Tasmania Senator for Senator for Tasmania South Australia New South Wales Senator the Hon Senator Senator Senator Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham Andrew Bragg Slade Brockman Carol Brown Matthew Canavan Senator for Senator for Senator for Senator for Tasmania Senator for Queensland South Australia New South Wales Western Australia Senator the Hon Senator the Hon Senator Senator Senator Kim Carr Michaelia Cash Claire Chandler Anthony Chisholm Raff Ciccone Senator for Victoria Senator for Senator for Tasmania Senator for Queensland Senator for Victoria Western Australia Senator the Hon Senator Senator Senator Senator the Hon Richard Colbeck Perin Davey Patrick Dodson Jonathon Duniam Don Farrell Senator for Tasmania Senator for Senator for Senator for Tasmania Senator for New South Wales Western Australia South Australia 1 Last updated 4 May 2021 46th Parliament: Senators Senator Senator the Hon Senator the Senator Senator Mehreen Faruqi David Fawcett Hon Concetta Alex Gallacher Katy Gallagher Fierravanti-Wells Senator for Senator for Senator for Senator for Australian New South Wales South Australia Senator for South Australia Capital Territory New South Wales Senator Senator Senator Senator Sarah Senator the Hon Nita Green Stirling Griff Pauline Hanson Hanson-Young Sarah Henderson Senator for Queensland Senator for Senator for Queensland Senator for Senator for -

Performance of Australia's Dairy Industry and the Profitability of Australian Dairy Farmers Since Deregulation in 2000

The Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee Performance of Australia's dairy industry and the profitability of Australian dairy farmers since deregulation in 2000 March 2021 © Commonwealth of Australia ISBN 978-1-76093-208-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, parliament House, Canberra Members Chair Senator Glenn Sterle ALP, WA Deputy Chair Senator Susan McDonald NATS, QLD Members Senator Gerard Rennick LP, QLD Senator Alex Gallacher ALP, SA Senator Nita Green (from 12.6.20) ALP, QLD Senator Janet Rice (to 6.10.20) AG, VIC Senator Peter Whish-Wilson (from 6.10.20) AG, TAS Participating Members Senator Pauline Hanson PHON, QLD Secretariat Gerry McInally, Committee Secretary Paula Waring, Principal Research Officer Ms Sarah Redden, Principal Research Officer Mr James Strickland, Principal Research Officer Joshua Wrest, Senior Research Officer Kaitlin Murphy, Senior Research Officer Michael Fisher, Research Officer Jason See, Administrative Officer PO Box 6100 Telephone: (02) 6277 3511 Parliament House Fax: (02) 6277 5811 CANBERRA ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] iii Contents Members ............................................................................................................................................. iii List of Recommendations -

Select Committee on the Effectiveness of the Australian Government's

The Senate Select Committee on the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s Northern Australia agenda Select Committee on the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s Northern Australia agenda Final report April 2021 © Commonwealth of Australia ISBN 978-1-76093-219-0 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Printed by Printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra. Members Chair Senator Murray Watt ALP, QLD Deputy Chair Senator Susan McDonald NATS, QLD Members Senator Patrick Dodson ALP, WA Senator Malarndirri McCarthy ALP, NT Senator Malcolm Roberts PHON, QLD Senator Rachel Siewert AG, WA Senator Dean Smith LP, WA Secretariat Ms Lee Katauskas, Committee Secretary Ms Fattimah Imtoual, Principal Research Officer Ms Adrienne White, Senior Research Officer Ms Ella Ross, Administrative Officer iii Contents Members ............................................................................................................................................. iii Terms of Reference .......................................................................................................................... vii Abbreviations and acronyms ........................................................................................................... ix List of Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

A PR Exercise Or Saving the Reef?

AUTHOR: Chris Calcino SECTION: GENERAL NEWS ARTICLE TYPE: NEWS ITEM AUDIENCE : 13,896 ~ isentia PAGE: 1 PRINTED SIZE: 1219.00cm2 REGION: QLD MARKET: Australia ASR: AUD 6,114 WORDS: 833 ITEM ID: 1182450742 08 OCT, 2019 HOW I'll FIX REEF PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY 1@#•l;@'·SU•tt1mrara ADVlCE eop,,g,, Aqercy l..m,led (CAI.) """"""' cw, or Cq,,,nghl Act 1968 (CwthJ,. 48" cw, Cairns Post, Cairns Page 1 of 4 Entsch claims he's already making waves as envoy I CHRIS CALCINO [email protected] THE Pederal Govern ment's Special Envoy for the Great Barrier Reef Warren Entsch is vowing that the position is more than just a public rela tions exercise. Four months into the job and he says he has launched a second Reef Clean effort to remove tonnes of rubbish from the sensitive ecosystem and established a biparti san parliamentary sup port group. Mr Entsch plans to bring VIPs to see how healthy the Reef is too. FULL STORY P4·5 A PR exercise or saving the Reef? Entsch's Special Envoy role raises many queries CHRIS CALCINO [email protected] The Leichhardt MP has WARREN Entsch's first four been afforded two extra staff months as Special Envoy for members at an estimated cost the Great Barrier Reef have of $200,000 to help carry out raised questions over whether the job, although the Federal the position is more than just a Government is keeping their PR exercise. AUTHOR: Chris Calcino SECTION: GENERAL NEWS ARTICLE TYPE: NEWS ITEM AUDIENCE : 13,896 ~ isentia PAGE: 1 PRINTED SIZE: 1219.00cm2 REGION: QLD MARKET: Australia ASR: AU D 6,114 WORDS: 833 ITEM ID: 1182450742 08 OCT, 2019 HOW I'll FIX REEF PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY Cop,rght Agenc; um ted (CAU ia!nsed COJJY a Copynght Act 1958 (C,...'fth) s 48A ttJP'f Cairns Post, Cairns Page 2 of 4 wages under wraps. -

Morrison's Miracle the 2019 Australian Federal Election

MORRISON'S MIRACLE THE 2019 AUSTRALIAN FEDERAL ELECTION MORRISON'S MIRACLE THE 2019 AUSTRALIAN FEDERAL ELECTION EDITED BY ANIKA GAUJA, MARIAN SAWER AND MARIAN SIMMS In memory of Dr John Beaton FASSA, Executive Director of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia from 2001 to 2018 and an avid supporter of this series of election analyses Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463618 ISBN (online): 9781760463625 WorldCat (print): 1157333181 WorldCat (online): 1157332115 DOI: 10.22459/MM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Scott Morrison Campaign Day 11. Photo by Mick Tsikas, AAP. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Figures . ix Plates . xiii Tables . .. xv Abbreviations . xix Acknowledgements . xxiii Contributors . xxv Foreword . xxxiii 1 . Morrison’s miracle: Analysing the 2019 Australian federal election . 1 Anika Gauja, Marian Sawer and Marian Simms Part 1. Campaign and context 2 . Election campaign overview . 21 Marian Simms 3 . The rules of the game . 47 Marian Sawer and Michael Maley 4 . Candidates and pre‑selection . .. 71 Anika Gauja and Marija Taflaga 5 . Ideology and populism . 91 Carol Johnson 6 . The personalisation of the campaign . 107 Paul Strangio and James Walter 7 . National polling and other disasters . 125 Luke Mansillo and Simon Jackman 8 . -

News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code) Bill 2020 [Provisions]

The Senate Economics Legislation Committee Treasury Laws Amendment (News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code) Bill 2020 [Provisions] February 2021 © Commonwealth of Australia ISBN 978-1-76093-178-0 (Printed Version) ISBN 978-1-76093-178-0 (HTML Version) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra Members Chair Senator Slade Brockman LP, WA Deputy Chair Senator Alex Gallacher ALP, SA Members Senator Andrew Bragg LP, NSW Senator Jenny McAllister ALP, NSW Senator Susan McDonald NATS, QLD Senator Rex Patrick IND, SA Participating Members Senator Sarah Hanson-Young AG, SA Secretariat Mr Mark Fitt, Committee Secretary Dr Andrew Gaczol, Principal Research Officer Ms Taryn Morton, Administrative Officer PO Box 6100 Phone: 02 6277 3540 Parliament House Fax: 02 6277 5719 Canberra ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] iii Contents Members ............................................................................................................................................. iii Chapter 1—Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2—Views on the bill.......................................................................................................... 19 Additional comments -

Australian Senators Contact Details

QLD SENATORS Party Senator Electorate Phone E-Mail Canberra Phone NAT Matthew Canavan (07) 4927 2003 [email protected] (02) 6277 3163 ALP Anthony Chisholm (07) 3881 3710 [email protected] (02) 6277 3103 ALP Nita Green (07) 4031 3498 [email protected] (02) 6277 3580 PHON Pauline Hanson (07) 3221 7644 [email protected] (02) 6277 3184 NAT Susan McDonald (07) 4771 3066 [email protected] (02) 6277 3635 LIB James McGrath (07) 5441 1800 [email protected] (02) 6277 3076 LIB Gerard Rennick (07) 3252 7101 [email protected] (02) 6277 3666 PHON Malcolm Roberts (07) 3221 9099 [email protected] (02) 6277 3694 LIB Paul Scarr (07) 3186 9350 [email protected] (02) 6277 3712 LIB Amanda Stoker (07) 3001 8170 [email protected] (02) 6277 3457 GREENS Larissa Waters (07) 3367 0566 [email protected] (02) 6277 3684 ALP Murray Watt (07) 5531 1033 [email protected] (02) 6277 3046 Click here to create a BCC email to all QLD Senators Back to Top NSW SENATORS Party Senator Electorate Phone E-Mail Canberra Phone ALP Tim Ayres (02) 9159 9330 [email protected] (02) 6277 3469 LIB Andrew Bragg (02) 9159 9320 [email protected] (02) 6277 3479 NAT Perin Davey (02) 9159 9310 [email protected] (02) 6277 3565 GREENS Mehreen Faruqi (02) 9211 1500 [email protected] (02) 6277 3095 LIB Concetta Fierravanti-Wells (02) 4226 1700 [email protected] (02) 6277 3098 LIB Hollie Hughes (02) 9159 9325 [email protected] (02) 6277 3610 ALP