Peripheral Arterial Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vasodilators for Primary Raynaud's Phenomenon

Vasodilators for primary Raynaud's phenomenon Author Su, KYC, Sharma, M, Kim, HJ, Kaganov, E, Hughes, I, Abdeen, MH, Ng, JHK Published 2021 Journal Title Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Version Version of Record (VoR) DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006687.pub4 Copyright Statement © 2021 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. This review is published as a Cochrane Review in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD006687.. Cochrane Reviews are regularly updated as new evidence emerges and in response to comments and criticisms, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews should be consulted for the most recent version of the Review. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/405317 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Cochrane Library Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Vasodilators for primary Raynaud's phenomenon (Review) Su KYC, Sharma M, Kim HJ, Kaganov E, Hughes I, Abdeen MH, Ng JHK Su KYC, Sharma M, Kim HJ, Kaganov E, Hughes I, Abdeen MH, Ng JH. Vasodilators for primary Raynaud's phenomenon. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD006687. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006687.pub4. www.cochranelibrary.com Vasodilators for primary Raynaud's phenomenon (Review) Copyright © 2021 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Cochrane Trusted evidence. Informed decisions. Library Better health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S HEADER........................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Inline-Supplementary-Material-1.Pdf

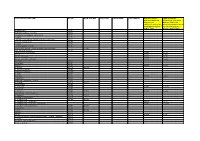

Appendix 1: STOPP/START criteria version 2 applied to the TRUST dataset Physiological system Criteria Criteria included Number (%) (The relevant () criteria for each participant were applied to the dataset and recorded in of Microsoft Office Excel ® (2013)) criteria included out of total criteria STOPP criteria Indication of medication A1. Any drug prescribed without an evidence-based clinical indication. X 1/3 (33.3) A2. Any drug prescribed beyond the recommended duration, where treatment duration is X well defined. A3. Any duplicate drug class prescription e.g. two concurrent NSAIDs, SSRIs, loop diuretics, ACE inhibitors, anticoagulants (optimisation of monotherapy within a single drug class should be observed prior to considering a new agent). Cardiovascular system B1. Digoxin for heart failure with preserved systolic ventricular function (no clear evidence X 7/13 (53.8) of benefit). B2. Verapamil or diltiazem with NYHA Class III or IV heart failure (may worsen heart failure). B3. Beta-blocker in combination with verapamil or diltiazem (risk of heart block). B4. Beta blocker with symptomatic bradycardia (< 50/min), type II heart block or complete heart block (risk of profound hypotension, asystole). B5. Amiodarone as first-line antiarrhythmic therapy in supraventricular tachyarrhythmias X (higher risk of side-effects than beta-blockers, digoxin, verapamil or diltiazem). B6. Loop diuretic as first-line treatment for hypertension (safer, more effective alternatives available). B7. Loop diuretic for dependent ankle oedema without clinical, biochemical evidence or radiological evidence of heart failure, liver failure, nephrotic syndrome or renal failure (leg elevation and /or compression hosiery usually more appropriate). B8. Thiazide diuretic with current significant hypokalaemia (i.e. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 De Juan Et Al

US 200601 10428A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 de Juan et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) METHODS AND DEVICES FOR THE Publication Classification TREATMENT OF OCULAR CONDITIONS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Eugene de Juan, LaCanada, CA (US); A6F 2/00 (2006.01) Signe E. Varner, Los Angeles, CA (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/427 (US); Laurie R. Lawin, New Brighton, MN (US) (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: Featured is a method for instilling one or more bioactive SCOTT PRIBNOW agents into ocular tissue within an eye of a patient for the Kagan Binder, PLLC treatment of an ocular condition, the method comprising Suite 200 concurrently using at least two of the following bioactive 221 Main Street North agent delivery methods (A)-(C): Stillwater, MN 55082 (US) (A) implanting a Sustained release delivery device com (21) Appl. No.: 11/175,850 prising one or more bioactive agents in a posterior region of the eye so that it delivers the one or more (22) Filed: Jul. 5, 2005 bioactive agents into the vitreous humor of the eye; (B) instilling (e.g., injecting or implanting) one or more Related U.S. Application Data bioactive agents Subretinally; and (60) Provisional application No. 60/585,236, filed on Jul. (C) instilling (e.g., injecting or delivering by ocular ion 2, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/669,701, filed tophoresis) one or more bioactive agents into the Vit on Apr. 8, 2005. reous humor of the eye. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2006/0110428A1 R 2 2 C.6 Fig. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2004/0224012 A1 Suvanprakorn Et Al

US 2004O224012A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2004/0224012 A1 Suvanprakorn et al. (43) Pub. Date: Nov. 11, 2004 (54) TOPICAL APPLICATION AND METHODS Related U.S. Application Data FOR ADMINISTRATION OF ACTIVE AGENTS USING LIPOSOME MACRO-BEADS (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 10/264,205, filed on Oct. 3, 2002. (76) Inventors: Pichit Suvanprakorn, Bangkok (TH); (60) Provisional application No. 60/327,643, filed on Oct. Tanusin Ploysangam, Bangkok (TH); 5, 2001. Lerson Tanasugarn, Bangkok (TH); Suwalee Chandrkrachang, Bangkok Publication Classification (TH); Nardo Zaias, Miami Beach, FL (US) (51) Int. CI.7. A61K 9/127; A61K 9/14 (52) U.S. Cl. ............................................ 424/450; 424/489 Correspondence Address: (57) ABSTRACT Eric G. Masamori 6520 Ridgewood Drive A topical application and methods for administration of Castro Valley, CA 94.552 (US) active agents encapsulated within non-permeable macro beads to enable a wider range of delivery vehicles, to provide longer product shelf-life, to allow multiple active (21) Appl. No.: 10/864,149 agents within the composition, to allow the controlled use of the active agents, to provide protected and designable release features and to provide visual inspection for damage (22) Filed: Jun. 9, 2004 and inconsistency. US 2004/0224012 A1 Nov. 11, 2004 TOPCAL APPLICATION AND METHODS FOR 0006 Various limitations on the shelf-life and use of ADMINISTRATION OF ACTIVE AGENTS USING liposome compounds exist due to the relatively fragile LPOSOME MACRO-BEADS nature of liposomes. Major problems encountered during liposome drug Storage in vesicular Suspension are the chemi CROSS REFERENCE TO OTHER cal alterations of the lipoSome compounds, Such as phos APPLICATIONS pholipids, cholesterols, ceramides, leading to potentially toxic degradation of the products, leakage of the drug from 0001) This application claims the benefit of U.S. -

Raynaud's Phenomenon and the Possible Use of Foods

JFS R: Concise Reviews/Hypotheses in Food Science Raynaud’s Phenomenon and the Possible Use of Foods CHRIS I. WRIGHT, CHRISTINE I. KRONER, AND RICHARD DRAIJER R: Concise Reviews in Food Science ABSTRACT: In this article we focus on the possible use of foods to alleviate Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP). RP is evoked, predominately, by cold and results in a potent vascular constriction of the microvascular blood vessels in the hands, thus leading to reduced hand blood flow and the elevation of pain sensation. To alleviate RP by diet, food components need to be able to promote hand skin blood flow, which may be achieved using fish oil, garlic, ginkgo biloba, L-carnitine, or inositol nicotinate, or to increase hand skin temperature, using evening primrose oil, ginkgo biloba, or inositol nicotinate. Although there are a number of studies documenting such improvements with these ingredients, they often are poorly designed. Hence, there is a need for more controlled studies to substantiate their use, but also to test alternative foods or target new ones. Therefore, we also discuss some alternate food options and briefly outline clinical drugs for the treatment of RP, as their mechanisms of action may also be possible targets for food. It is the intention of this article to address the research needs of this field and to provide a better understanding of alternative options for those with RP. Keywords: Raynaud’s, vascular constriction, dietary intervention, nutraceutical, functional foods Introduction Mahoney 1999; Generini and others 2003; Herrick 2003); however, lit- here are a growing number of studies focusing on the con- tle work has been published on the use of foods as a complementary Tceivable health benefits of foods, botanicals, and supplements treatment for RP patients or as a safeguard for those at high or future (Boelsma and others 2001; Green and others 2003). -

Poisons and Narcotic Drugs (Amendment) Ordinance 1988

AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Poisons and Narcotic Drugs (Amendment) Ordinance 1988 No. 96 of 1988 I, THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL of the Commonwealth of Australia, acting with the advice of the Federal Executive Council, hereby make the following Ordinance under the Seat of Government (Administration) Act 1910. Dated 15 December 1988 N. M. STEPHEN Governor-General By His Excellency’s Command, CLYDE HOLDING Minister of State for the Arts and Territories An Ordinance to amend the Poisons and Narcotic Drugs Ordinance 1978 Short title 1. This Ordinance may be cited as the Poisons and Narcotic Drugs (Amendment) Ordinance 1988.1 Commencement 2. This Ordinance commences on such date as is fixed by the Minister by notice in the Gazette. Principal Ordinance 3. In this Ordinance, “Principal Ordinance” means the Poisons and Narcotic Drugs Ordinance 1978.2 (Ord. 79/88)—Cat. No. Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au 2 Poisons and Narcotic Drugs (Amendment) No. 96, 1988 Substances to which Division applies 4. Section 27B of the Principal Ordinance is amended by adding at the end the following paragraphs: “; (f) follicle stimulating hormone; (g) luteinising hormone; (h) thalidomide.”. Grant of authorisation 5. Section 27E of the Principal Ordinance is amended— (a) by omitting from paragraph (1) (a) “or cyclofenil” and substituting “, cyclofenil, follicle stimulating hormone or luteinising hormone”; (b) by omitting from paragraph (1) (b) “and”; and (c) by adding at the end of subsection (1) the following word and paragraph: “; and (d) in the case of an application that relates to thalidomide— the applicant is a specialist physician with no less than 5 years’ experience in the treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum.”. -

List of Union Reference Dates A

Active substance name (INN) EU DLP BfArM / BAH DLP yearly PSUR 6-month-PSUR yearly PSUR bis DLP (List of Union PSUR Submission Reference Dates and Frequency (List of Union Frequency of Reference Dates and submission of Periodic Frequency of submission of Safety Update Reports, Periodic Safety Update 30 Nov. 2012) Reports, 30 Nov. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

Examination of Antimicrobial Activity of Selected Non-Antibiotic Medicinal Preparations

Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica ñ Drug Research, Vol. 69 No. 6 pp.1368ñ1371, 2012 ISSN 0001-6837 Polish Pharmaceutical Society EXAMINATION OF ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF SELECTED NON-ANTIBIOTIC MEDICINAL PREPARATIONS HANNA KRUSZEWSKA1*, TOMASZ ZAR BA1 and STEFAN TYSKI1,2 1National Medicines Institute, Department of Antibiotics and Microbiology, 30-34 Che≥mska St., 00-725 Warszawa, Poland 2 Medical University of Warsaw, Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology, 3 Oczki St., 02-007 Warszawa, Poland Abstract: The aim of this study was to detect and characterize the antimicrobial activity of non-antibiotic drugs, selected from the pharmaceutical products analyzed during the state control performed in National Medicines Institute, Warszawa, Poland. In 2010, over 90 pharmaceutical preparations have been randomly chosen from different groups of drugs. The surveillance study was performed on standard ATCC microbial strains used for drug control: S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa and C. albicans. It was shown that the drugs listed below inhib- ited growth of at least one of the examined strains: Arketis 20 mg tab. (paroxetine), Buvasodil 150 mg tab. (buflomedile), Halidor 100 mg tab. (bencyclane), Hydroxyzinum espefa 25 mg tab. (hydroxyzine), Norifaz 35 mg tab. (risedronate), Strattera 60 mg cap. (atomoxetine), Tamiflu 75 mg tab. (oseltamivir), Valpro-ratiopharm Chrono 300 mg tab. with longer dissolution (valproate), Vetminth oral paste 24 g+3 g/100 mL (niclozamide, oxybendazol). Strattera cap. showed broad activity spectrum. It inhibited growth of -

Partial Agreement in the Social and Public Health Field

COUNCIL OF EUROPE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS (PARTIAL AGREEMENT IN THE SOCIAL AND PUBLIC HEALTH FIELD) RESOLUTION AP (88) 2 ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES WHICH ARE OBTAINABLE ONLY ON MEDICAL PRESCRIPTION (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 22 September 1988 at the 419th meeting of the Ministers' Deputies, and superseding Resolution AP (82) 2) AND APPENDIX I Alphabetical list of medicines adopted by the Public Health Committee (Partial Agreement) updated to 1 July 1988 APPENDIX II Pharmaco-therapeutic classification of medicines appearing in the alphabetical list in Appendix I updated to 1 July 1988 RESOLUTION AP (88) 2 ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES WHICH ARE OBTAINABLE ONLY ON MEDICAL PRESCRIPTION (superseding Resolution AP (82) 2) (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 22 September 1988 at the 419th meeting of the Ministers' Deputies) The Representatives on the Committee of Ministers of Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, these states being parties to the Partial Agreement in the social and public health field, and the Representatives of Austria, Denmark, Ireland, Spain and Switzerland, states which have participated in the public health activities carried out within the above-mentioned Partial Agreement since 1 October 1974, 2 April 1968, 23 September 1969, 21 April 1988 and 5 May 1964, respectively, Considering that the aim of the Council of Europe is to achieve greater unity between its members and that this -

Quality Issues in Caring for Older People

Doctoral Thesis - Tesis Doctoral Quality issues in caring for older people: • Appropriateness of transition from long-term care facilities to acute hospital care • Potentially inappropriate medication: development of a European list Anna Renom Guiteras Prof. Gabriele Meyer Prof. Ramón Miralles Basseda Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Halle (Saale) & Barcelona, Catalonia University of Witten/Herdecke Spain Witten Germany Programa de doctorat en Medicina Departament de Medicina, Facultat de Medicina Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Barcelona, 2015 13 Contents 15 1. Introduction • Research context • Background of the research topics • Pesetaio of the ailes 23 2. Summary and discussion of the results 31 3. Conclusions 37 4. References 47 5. Articles • Article 1: Renom-Guiteras A, Uhrenfeldt L, Meyer G, Mann E. Assessment tools for determining appropriateness of admission to acute care of persons transferred from long-term care facilities: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:80 • Article 2: Renom-Guiteras A, Meyer G, Thürmann PA. The EU(7)-PIM list: a list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people consented by experts from seven European countries. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(7):861-75 77 6. Annexes • Annex 1.1 (article 1) - Additional file 1: Studies dealing with assessment tools for determining appropriateness of hospital admissions among residents of LTC facilities. • Annex 1.2 (article 1) - Additional file 2: Characteristics of the assessment tools for determining appropriateness of hospital admissions among residents of LTC facilities. • Annex 2.1 (article 2) - Appendix 1: Complete EU(7)-PIM list • Annex 2.2 (article 2) - Appendix 2: Questionable Potentially Inappropriate Medications (Questionable PIM): results of the Delphi survey. -

Identification of Potentially Inappropriate Medications with Risk

Journal name: Clinical Interventions in Aging Article Designation: Original Research Year: 2019 Volume: 14 Clinical Interventions in Aging Dovepress Running head verso: Aguiar et al Running head recto: Aguiar et al open access to scientific and medical research DOI: 192252 Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Identification of potentially inappropriate medications with risk of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events among elderly patients in ambulatory setting and long-term care facilities This article was published in the following Dove Medical Press journal: Clinical Interventions in Aging João Pedro Aguiar1 Purpose: Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are extremely common among the elderly, but Luís Heitor Costa2 information on the use of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) with cardiovascular Filipa Alves da Costa3,4 risk is scarce. We aimed to determine the prevalence of PIMs with risk of cardiac and cere- Hubert GM Leufkens5 brovascular adverse events (CCVAEs), including major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular Ana Paula Martins1 events (MACCE). Patients and methods: A cross-sectional study was performed using a convenience sample 1Research Institute for Medicines (iMED.ULisboa), Faculdade de from four long-term care facilities and one community pharmacy in Portugal. Patients were For personal use only. Farmácia, Universidade de Lisboa, included if they were aged 65 or older and presented at least one type of medication in their 2 Lisboa, Portugal; Serviço de medical and pharmacotherapeutic records from 2015 until December 2017. The main outcome Medicina Interna, Centro Hospitalar Psiquiátrico de Lisboa (CHPL), Lisboa, was defined as the presence of PIMs with risk of MACCE and was assessed by applying a Portugal; 3Centro de Investigação PIM-MACCE list that was developed from a previous study.