The Role & Larger Meaning of Sakhi in Indian Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

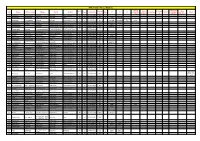

Farmer Database

KVK, Trichy - Farmer Database Animal Biofertilier/v Gende Commun Value Mushroo Other S.No Name Fathers name Village Block District Age Contact No Area C1 C2 C3 Husbandry / Honey bee Fish/IFS ermi/organic Others r ity addition m Enterprise IFS farming 1 Subbaiyah Samigounden Kolakudi Thottiyam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 57 9787932248 BC 2 Manivannan Ekambaram Salaimedu, Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 58 9787935454 BC 4 Ixora coconut CLUSTERB 3 Duraisamy Venkatasamy Kolakudi Thottiam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787936175 BC Vegetable groundnut cotton EAN 4 Vairamoorthy Aynan Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 33 9787936969 bc jasmine ixora 5 subramanian natesan Sirupathur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787942777 BC Millet 6 Subramaniyan Thirupatur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787943055 BC Tapioca 7 Saravanadevi Murugan Keelakalkandarkottai THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI F 42 9787948480 SC 8 Natarajan Perumal Kattukottagai UPPILIYAPURAM TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 47 9787960188 BC Coleus 9 Jayanthi Kalimuthu top senkattupatti UPPILIYAPURAM Tiruchirappalli F 41 9787960472 ST 10 Selvam Arunachalam P.K.Agaram Pullampady TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 23 9787964012 MBC Onion 11 Dharmarajan Chellappan Peramangalam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 68 9787969108 BC sugarcane 12 Sabayarani Lusis prakash Chinthamani Musiri Tiruchirappalli F 49 9788043676 BC Alagiyamanavala 13 Venkataraman alankudimahajanam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 67 9788046811 BC sugarcane n 14 Vijayababu andhanallur andhanallur TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 30 9788055993 BC 15 Palanivel Thuvakudi THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 65 9788056444 -

Ascetic Yogas the PATH of SELF-REALIZATION Robert Koch Robert Koch Was Initiated As Sri Patraka Das at the Lotus Feet of H.H

Sri Jagannath Vedic Center, USA Drig dasa August 23, 2002 Ukiah, USA © Robert Koch, 2002 – Published in Jyotish Digest 1 Ascetic Yogas THE PATH OF SELF-REALIZATION Robert Koch Robert Koch was initiated as Sri Patraka Das at the lotus feet of H.H. Sri Srimad A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada in March, 1971. He lived in India for 6 years till 1983, studying Jyotish and has received certificate of commendation for spreading Hindu astrology in the USA, from the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, in 1999. Web site: http://www.robertkoch.com n the first Canto of the great Vedic Purana Srimad Bhagavatam, there is a very interesting and instructional conversation that took place between a bull personifying I Dharma, or religion, and Bhumi, the mother earth in the form of a cow. The bull was standing on one leg, suggesting that that one out of four pillars of religious principles (represented by each leg of Dharma, the bull) was still existing, and that in itself was faltering with the progress of Kali-yuga. The four legs of the Dharma are truthfulness, cleanliness, mercy, and austerity. If most or all of these legs of Dharma are broken, or if 3 out of 4 Dharmic principles exist very rarely, in human society, then we can be confident that Kali-yuga – the age of quarrel and darkness – is well upon us. Given that there are some rare souls existing who speak and live the Supreme Absolute Truth, as is found in various Vedic literatures, the remaining leg of truthfulness still exists. Such persons are characterized by complete self-control, or the ability to detach themselves from the relative world of the senses and the objects of sense pleasure. -

Baghawat Geeta, Class 13

Baghawat Geeta, Class 13 Greetings All, Gita, Chapter # 2, Samkhya Yoga: Swamiji starts off by reminding us that Vyasa now presents Arjuna as a seeker of moksha. The fundamental human problem characterized by Raga (Likes), Dvesha (Dislikes) and Moha (delusion) is also called Samsara. Due to attachment, when we lose a person or an object, it causes us Shoka. In this state of Shoka our mind loses its discriminating faculty and is called Moha. This is the situation faced by Arjuna in battlefield. While we try making adjustments to the external world to solve such an internal problem, it only acts as a palliative or a first aid rather than as a remedy. In such a situation the aggrieved person should discuss his helplessness in solving the problem, and this state of helplessness is called Karpanya bhava or Dainya bhava. While Arjuna has discovered his problem he has not yet arrived at the helpless stage, the second stage of problem solving. Shloka #5: Arjuna says: If I fight and kill my two Gurus, I will only remember how they struggled and died in battle. Every moment I will remember how I killed Bhishma and Drona. My other option is not to fight and retire to the forest, where I will have to live on alms. Swamiji says Arjuna has to decide which course of action to take. He chooses Adharma. He feels he will be better off living in forest, on alms. For a Kshatriya and Grihastha, Bhiksha is not allowed. Giving up one’s Sva-Dharma is also a sin. -

Prisoner's Contact with Their Families

TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page No. List of Tables ii The Research Team iii Acknowledgments iv Glossary of Terms used in Prisons v Chapter I: Introduction 1 Chapter II: Review of Literature 5 Chapter III: Research Methodology 9 Chapter IV: Procedure and Practice for Prisoners’ Communication 14 with the Outside Chapter V: Communication Facilities: Processes, 35 Experiences and Perceptions Chapter VI: Good Practices and Recommendations 68 References 80 Appendix 81 End Notes 88 i List of Tables Title Page No. Table 3.1 Research Sites 10 Table 3.2. Number of Respondents (State-wise) 10 Table 4.1: Procedures for Prisoners’ Meetings with Visitors 14 Table 4.2. Facilities for Telephonic Communication 27 Table 4.3: Facilities for Communication through Inland-letters and Postcards 28 Table 4.4: Feedback and Concerns Shared about Practice and Procedure 29 ii The Research Team Researcher Ms. Subhadra Nair Data Collection Team Ms. Subhadra Nair Ms. Surekha Sale Ms. Pradnya Shinde Ms. Meenal Kolatkar Ms. Priyanka Kamble Ms. Karuna Sangare Ms. Komal Phadtare Report Writing Team Ms. Subhadra Nair Prof. Vijay Raghavan Dr. Sharon Menezes Ms. Devayani Tumma Ms. Krupa Shah Cover-page, Report Design and Layout Tabish Ahsan Administration Support Team Mr. Rajesh Gajbiye Ms. Shital Sakharkar Ms. Harshada Sawant Project Directors Prof. Vijay Raghavan Dr. Sharon Menezes iii Acknowledgements This study has reached its completion due to the support received from the Prison Departments of different states. We especially wish to thank the following persons for facilitating the study. 1. Shri S.N. Pandey, Director General (Prisons & Correctional Services), Mumbai, Maharashtra. 2. -

Adv-Aug-For-Web-3598

Aug 2018 | Vol 4 | Issue 5 www.advantagekarnataka.in Frames Bangalore Fostering of its Startup Potential Glory NGMA Exhibits Jitendra Arya’s Ouevre August 2018 ADVANTAGE KARNATAKA 2 August 2018 August 2018 3 ADVANTAGE KARNATAKA EDITORIAL angalore, the Startup Capital of India, is scaling new heights among world Content cities by providing the ideal ecosystem for startups to nourish. According to a report published recently by US venture capital and startup database, B 6 Bangalore Fostering its Startup Potential Bangalore ranked first among Indian cities to have highest number of startup investment rounds greater than $100 million since 2014. The report also states that 8 Major Event for Aerospace Manufacture Bangalore runs ahead of foreign cities like London (19), Boston (13), and Tel Aviv (2), which are often regarded as strong startups hubs around the world. 10 Creating Priorities for Digitisation Moreover, Bangalore has been selected for the launch of Defence India Start Up Govt. Aims to Make State Future-Ready: K J George Challenge, an initiative of Defence Innovation Organisation (DIO) under the aegis 12 of Department of Defence Production, Ministry of Defence. The Defence India Start 14 Focus on Making Transport Corporations Profitable up Challenge, aimed at supporting innovators to create prototypes, commercialise Editorial Advisory Board products or solutions based on advanced technologies in the area of national 16 Toyota Aims High in Diesel Engine Manufacture security, will further the startup potential of the city which is already home to several Dr. C.G. Krishnadas Nair startups in aerospace and defence sector. 20 Boeing’s HorizonX India Innovation Challenge Dr. -

Arsha November 08 Wrapper Final

Arsha Vidya Newsletter Rs. 15/- Vol. 11 November 2010 Issue 11 Arsha Vidya Pitham Arsha Vidya Gurukulam Arsha Vidya Gurukulam Swami Dayananda Ashram Institute of Vedanta and Institute of Vedanta and Sanskrit Sri Gangadhareswar Trust Sanskrit Sruti Seva Trust Purani Jhadi, Rishikesh P.O. Box No.1059 Anaikatti P.O. Pin 249 201, Uttarakhanda Saylorsburg, PA, 18353, USA Coimbatore 641 108 Ph.0135-2431769 Tel: 570-992-2339 Tel. 0422-2657001, Fax: 0135 2430769 Fax: 570-992-7150 Fax 91-0422-2657002 Website: www.dayananda.org 570-992-9617 Web Site : "http://www.arshavidya.in" Email: [email protected] Web Site : "http://www.arshavidya.org" Email: [email protected] Books Dept. : "http://books.arshavidya.org" Board of Trustees: Chairman: Board of Directors: Board of Trustees: Swami Dayananda President: Paramount Trustee: Saraswati Swami Dayananda Saraswati Swami Dayananda Saraswati Trustees: Vice Presidents: Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati Swami Suddhananda Chairman: Swami Tattvavidananda Saraswati Swami Aparokshananda R. Santharam Secretary: Swami Hamsananda Anand Gupta Trustees: Sri Rajnikant C. Soundar Raj Treasurer: Sri M.G. Srinivasan Piyush and Avantika Shah P.R.Ramasubrahmaneya Rajhah Ravi Sam Asst. Secretary: Arsha Vijnana Gurukulam N.K. Kejriwal Dr. Carol Whitfield 72, Bharat Nagar T.A. Kandasamy Pillai Amaravathi Road, Nagpur Ravi Gupta Maharashtra 410 033 Directors: Phone: 91-0712-2523768 Drs.N.Balasubramaniam (Bala) & Arul M. Krishnan Emai: [email protected] Ajay & Bharati Chanchani Dr.Urmila Gujarathi Secretary: Board of Trustees -

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

Psyphil Celebrity Blog Covering All Uncovered Things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies List New Films List Latest Tamil Movie List Filmography

Psyphil Celebrity Blog covering all uncovered things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies list new films list latest Tamil movie list filmography Name: Vijay Date of Birth: June 22, 1974 Height: 5’7″ First movie: Naalaya Theerpu, 1992 Vijay all Tamil Movies list Movie Y Movie Name Movie Director Movies Cast e ar Naalaya 1992 S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sridevi, Keerthana Theerpu Vijay, Vijaykanth, 1993 Sendhoorapandi S.A.Chandrasekar Manorama, Yuvarani Vijay, Swathi, Sivakumar, 1994 Deva S. A. Chandrasekhar Manivannan, Manorama Vijay, Vijayakumar, - Rasigan S.A.Chandrasekhar Sanghavi Rajavin 1995 Janaki Soundar Vijay, Ajith, Indraja Parvaiyile - Vishnu S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sanghavi - Chandralekha Nambirajan Vijay, Vanitha Vijaykumar Coimbatore 1996 C.Ranganathan Vijay, Sanghavi Maaple Poove - Vikraman Vijay, Sangeetha Unakkaga - Vasantha Vaasal M.R Vijay, Swathi Maanbumigu - S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Keerthana Maanavan - Selva A. Venkatesan Vijay, Swathi Kaalamellam Vijay, Dimple, R. 1997 R. Sundarrajan Kaathiruppen Sundarrajan Vijay, Raghuvaran, - Love Today Balasekaran Suvalakshmi, Manthra Joseph Vijay, Sivaji - Once More S. A. Chandrasekhar Ganesan,Simran Bagga, Manivannan Vijay, Simran, Surya, Kausalya, - Nerrukku Ner Vasanth Raghuvaran, Vivek, Prakash Raj Kadhalukku Vijay, Shalini, Sivakumar, - Fazil Mariyadhai Manivannan, Dhamu Ninaithen Vijay, Devayani, Rambha, 1998 K.Selva Bharathy Vandhai Manivannan, Charlie - Priyamudan - Vijay, Kausalya - Nilaave Vaa A.Venkatesan Vijay, Suvalakshmi Thulladha Vijay 1999 Manamum Ezhil Simran Thullum Endrendrum - Manoj Bhatnagar Vijay, Rambha Kadhal - Nenjinile S.A.Chandrasekaran Vijay, Ishaa Koppikar Vijay, Rambha, Monicka, - Minsara Kanna K.S. Ravikumar Khushboo Vijay, Dhamu, Charlie, Kannukkul 2000 Fazil Raghuvaran, Shalini, Nilavu Srividhya Vijay, Jyothika, Nizhalgal - Khushi SJ Suryah Ravi, Vivek - Priyamaanavale K.Selvabharathy Vijay, Simran Vijay, Devayani, Surya, 2001 Friends Siddique Abhinyashree, Ramesh Khanna Vijay, Bhumika Chawla, - Badri P.A. -

Kamandakiya Nitisara; Or, the Elements of Polity, in English;

^-v^lf - CAMANDAKIYA NITISARA OR THE ELEMENTS OF POLITY (IN ENGLISH.) -»r—8 6 £::^»» ^sjfl • EDITED AND PUBLISHED BY MANMATHA NATH DUTT, M.A., M.R.A.S. Rector, Keshub Academy ; ulhor of the English Translations of the Ramayana, S^rtniadbhagct' vatam, Vishnupuranam, Mahabharata, Bhagavai-Gita and other ivorks. > i . 1 J ,',''' U 3© I 3 t > « t , ^ -I > J J J I > ) > 3 ) ) 11 CA LCUTTA: Printed by H. C. Dass, Elysium Press, 65/2 Beadon Streei. 180O, CARPENTIER • • • • •« • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • I .« « _• t . • • • « • • «! C < C < C I < C ( t ( I < 4 • • • . INTRODUCTION. -:o:- ^HE superiority of the ancient Hindus in metaphysical and theological disquisitions has been established beyond all doubts. Our literature abounds in trca- Polity: its The science Of ^ ^^^^^^ for philosophical discus- sions, sound reasonings and subtle inferences regarding many momentous problems of existence, have not been beaten down by the modern age of culture and enlighten- ment. The world has all along been considered by the ancient Hindu writers as a flood-gate of miseries of existence, and the summum bonum of human existence is, in their view, the unification of the humanity with the divinity. The chief aim of all the ancient writers of India has been to solve the mighty problem, namely, the cessation of miseries of existence and the attainment of the God-head. Admitting their exalted superiority in matters of philosophical and theological speculation, some people of the present generation boldly launch the theory that our literature lacks in works which may serve as a guidance of practical life. To disabuse the popular mind of this perilous misconception, we might safely assert that Hindu writers paid no less attention to practical morals and politics. -

Samskara-By-Ur-Anantha-Murthy.Pdf

LITERATURE ~O} OXFORD"" Made into a powerful, award-winning film in 1970, this important Kannada novel of the sixties has received widespread acclaim from both critics and general read ers since its first publication in 1965. As a religious novel about a decaying brahmin colony in the south Indian village of Karnataka, Samskara serves as an allegory rich in realistic detail, a contemporary reworking of ancient Hindu themes and myths, and a serious, poetic study of a religious man living in a community of priests gone to seed. A death, which stands as the central event in the plot, brings in its wake a plague, many more deaths, live questions with only dead answers, moral chaos, and the rebirth of one man. The volume provides a useful glos sary of Hindu myths, customs, Indian names, flora, and other terms. Notes and an afterword enhance the self contained, faithful, and yet readable translation. U.R. Anantha Murthy is a well-known Indian novelist. The late A.K. Ramanujan w,as William E. Colvin Professor in the Departments of South Asian Languages and Civilizations and of Linguistics at the University of Chicago. He is the author of many books, including The Interior Landscape, The Striders, The Collected Poems, and· several other volumes of verse in English and Kannada. ISBN 978-0-19-561079-6 90000 Cover design by David Tran Oxford Paperbacks 9780195 610796 Oxford University Press u.s. $14.95 1 1 SAMSKARA A Rite for a Dead Man Sam-s-kiira. 1. Forming well or thoroughly, making perfect, perfecting; finishing, refining, refinement, accomplishment. -

SACHI,Society for Art & Cultural Heritage of India

SACHI, Society for Art & Cultural Heritage of India in collaboration with The Department of Religious Studies and Center for South Asia at Stanford University Invites You to Join an Illustrated Talk cum Dance on Thyagaraja Ramayanam presented by Ananda Shankar Jayant India's eminent Bharatanatyam dance artist and leading choreographer Thursday, Nov. 13, 2014, 7 p.m. Cummings Art Bldg., Classroom ART 2 435 Lausen Mall, Stanford University (corner of History Bldg., and Lausen Mall) Free Admission and Open to the Public; Recommended parking, around the Oval ‘As long as the mountains stand and rivers flow on earth, so long shall remain the legend of Ramayana.’ Sri Rama and the Ramayana have inspired seers and scholars across eons and centuries. It is a story that transcends space and time - a tale of love, devotion, and sacrifice. Rama's story has been written, interpreted and commented upon by mystic sages, poets and musicians, and by the Bhakta (devotee) with utmost reverence and ecstatic devotion. Telling and re-telling the Ramayana has not tired the storyteller, the listener or the viewer! While the essential story of the Ramayana remains the same, its various interpretations through the ages, represent a great diversity in the way the story and its characters are presented. In 1986 the artist Ananda Shankar choreographed and performed the Thyagaraja Ramayanam which explored the character of Rama through the vision of the poet saint Thyagaraja In an all time favorite work for the artist, Ananda will introduce and discuss select episodes/songs from the Ramayana as visualized by Thyagaraja and portray some in visual dance format set to Thyagaraja's music with select Valmiki Ramayana shlokas in enacting roles from the epic story. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ