Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can Islam Accommodate Homosexual Acts? Qur’Anic Revisionism and the Case of Scott Kugle Mobeen Vaid

ajiss34-3-final_ajiss 8/16/2017 1:01 PM Page 45 Can Islam Accommodate Homosexual Acts? Qur’anic Revisionism and the Case of Scott Kugle Mobeen Vaid Abstract Reformist authors in the West, most notably Scott Kugle, have called Islam’s prohibition of liwāṭ (sodomy) and other same-sex be - havior into question. Kugle’s “Sexuality, Diversity, and Ethics in the Agenda of Progressive Muslims” ( Progressive Muslims : 2003) and Homosexuality in Islam (2010) serve as the scholarly center for those who advocate sanctioning same-sex acts. Kugle traces the heritage of the Lot narrative’s exegesis to al-Tabari (d. 310/923), which, he contends, later exegetes came to regard as theologically axiomatic and thus beyond question. This study argues that Kugle’s critical methodological inconsistencies, misreading and misrepre - sentation of al-Tabari’s and other traditional works, as well as the anachronistic transposition of modern categories onto the classical sources, completely undermine his argument. Introduction Islam, like other major world religions (with the very recent exception of certain liberal denominations in the West), categorically prohibits all forms of same- sex erotic behavior. 1 Scholars have differed over questions of how particular homosexual acts should be technically categorized and/or punished, but they Mobeen Vaid (M.A. Islamic studies, Hartford Seminary) is a Muslim public intellectual and writer. A regular contributor to muslimmatters.org, his writings center on how traditional Islamic norms and frames of thinking intersect the modern world. As of late, he has focused on Islamic sexual and gender norms. Vaid also speaks at confessional conferences, serves as an advisor to Muslim college students, and was campus minister for the Muslim community while a student at George Mason University. -

Madhhab Och Taqlid

Madhhab och taqlid Argumenten för de fyra rättsskolornas giltighet samt nödvändigheten av taqlid Författare: Farhad Abdi 1 Innehållsförteckning Inledning ................................................................................................................................. 3 Bakgrund ............................................................................................................................ 3 Definitioner ............................................................................................................................ 3 Syfte och frågeställning .......................................................................................................... 5 Några bevis för att muslimer måste följa de lärda.................................................................. 5 Vad krävs för att bli en mujtahid? .......................................................................................... 6 1. Kunskap i det arabiska språket och dess grammatik på en hög nivå. ...................... 7 2. Hafidh al-Quran ....................................................................................................... 9 3. Hafidh al-hadith ..................................................................................................... 10 4. Mustalah al-Hadith ................................................................................................. 14 5. Kunskap i ’ilm al-nasikh wa al-mansukh ............................................................... 16 6. Asbab al-nozool .................................................................................................... -

The Naqshbandi-Haqqani Order, Which Has Become Remarkable for Its Spread in the “West” and Its Adaptation to Vernacular Cultures

From madness to eternity Psychiatry and Sufi healing in the postmodern world Athar Ahmed Yawar UCL PhD, Division of Psychiatry 1 D ECLARATION I, Athar Ahmed Yawar, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 2 A BSTRACT Problem: Academic study of religious healing has recognised its symbolic aspects, but has tended to frame practice as ritual, knowledge as belief. In contrast, studies of scientific psychiatry recognise that discipline as grounded in intellectual tradition and naturalistic empiricism. This asymmetry can be addressed if: (a) psychiatry is recognised as a form of “religious healing”; (b) religious healing can be shown to have an intellectual tradition which, although not naturalistic, is grounded in experience. Such an analysis may help to reveal why globalisation has meant the worldwide spread not only of modern scientific medicine, but of religious healing. An especially useful form of religious healing to contrast with scientific medicine is Sufi healing as practised by the Naqshbandi-Haqqani order, which has become remarkable for its spread in the “West” and its adaptation to vernacular cultures. Research questions: (1) How is knowledge generated and transmitted in the Naqshbandi- Haqqani order? (2) How is healing understood and done in the Order? (3) How does the Order find a role in the modern world, and in the West in particular? Methods: Anthropological analysis of psychiatry as religious healing; review of previous studies of Sufi healing and the Naqshbandi-Haqqani order; ethnographic participant observation in the Naqshbandi-Haqqani order, with a special focus on healing. -

Condemnations of Suicide Bombing by Muslims

IHSANIC INTELLIGENCE Condemnations of Suicide Bombings by Muslims Collated by Ihsanic Intelligence (www.ihsanic-intelligence.com) The following Sunni Muslim scholars, academics, thinker and political leaders have publicly condemned suicide bombing. Their public condemnations have been used as evidences for the conclusions reached in ‘The Hijacked Caravan: Refuting Suicide Bombings as Martyrdom Operations in Contemporary Jihad Strategy.’ • Suicide Bombing is anathema, antithetical and abhorrent to Sunni Islam • Suicide Bombing is a legally reprehensible innovation in the tradition of Sunni Islam • Suicide Bombing is morally a sin combining suicide and murder • Suicide Bombing is theologically an act of eternal damnation for all perpetrators Islamic Scholars Shaykh Abu Bakr al-’Attas, Lebanon ‘Ba ‘Alawi Shaykhs, Yemen Shaykh Dr. Gibril Haddad, Syria Mufti Taqiuddin Usmani, Pakistan Imam Faisel Abdul Rauf, USA Imam Zaid Shakir, USA Shaykh Abdal-Hakim Murad, Cambridge, UK Shaykh Dr. Abdalqadir As-Sufi, UK Shaykh Hamza Yusuf Hanson, USA Shaykh Nuh Hah Mim Keller, Jordan Muslim Academics and Thinkers Professor Syed Hussein al-’Attas, Malaysia Professor Sari Nusseibeh, Occupied Palestinian Territories Professor Akbar Ahmad, USA Professor Ziauddin Sardar, UK Professor Talal Asad, USA Fethullan Gülen, Turkey Bookwright, Denmark Harun Yahya, Turkey Enver Masud, USA Political Leaders King Abdullah II, Jordan Prince El-Hassan bin Talal, Jordan Dr. Mahathir bin Mohammad, Malaysia 7 are descendants of Prophet Muhammad 7 are Oxbridge graduates 7 are converts to Islam 7 are Arabs, 4 are Americans, 3 are Pakistanis, 3 are British, 2 are Turks, 2 are Malaysian IHSANIC INTELLIGENCE ISLAMIC SCHOLARS Shaykh Abu Bakr al-’Attas, Instructor, Muhammad al-Fatih Institute, Beirut, Lebanon Ba ‘Alawi Sheikhs, Yemen Shaykh Dr. -

NEWSLETTER – SPECIAL RAMADAN UPDATE Inclusivity, Authenticity, Compassion

ISSUE 6 RAMADAN 1441 / MAY 2020 CAMBRIDGE CENTRAL MOSQUE NEWSLETTER – SPECIAL RAMADAN UPDATE INCLUSIVITY, AUTHENTICITY, COMPASSION Message from Yusuf Islam Peace be upon you and the mercy and blessings of Allah. We’ve all been forced into a state of I’tikaf, and so has most of the world, non-Muslims included. These are strange times indeed, and there are things for us to ponder. So I wish you all the blessings of this holy month and to remember that the main purpose of this month of fasting is to increase our remembrance and closeness to Allah. In the Qur’an we read: ‘Remember Me and I will remember you; be grateful to Me and don’t deny Me.’ This is the heart and the spiritual goal of our fasting and our abstinence in this month. But there is also an important accessory that we should remember connected to our prayers and our ibada, and this is to increase our knowledge and understanding through study and reading, something we have more time for now because of the lockdown. So, while we’re confined in this time, for however many weeks or months, let the power of contemplation become the means to lift us up out and beyond the limits of this earthly imprisonment, and let our spirits fly. As-salamu alaykum wa-rahmatu’Llah! cambridge central mosque cambridge central mosque LIVEMEDIA RAMADAN TV THE MOSQUE GOES ONLINE RAMADAN TV The lockdown means that the Mosque has we have been delighted to announce the launch of been closed for prayer since the middle of March. -

The Destiny of Woman: Feminism & Femininity in Traditional Islam by Sanaa Mohiuddin B.A. in Classics, June 2007, Wellesley C

The Destiny of Woman: Feminism & Femininity in Traditional Islam by Sanaa Mohiuddin B.A. in Classics, June 2007, Wellesley College A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts January 19, 2018 Thesis directed by Kelly Pemberton Associate Professor of Religion and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies © Copyright 2018 by Sanaa Mohiuddin All rights reserved ii Dedication To my parents, Drs. Mohammed & Sabiha Mohiuddin iii Table of Contents Dedication …………...……………………………………………………….………..…iii Note on Transliteration …………………………………………………………......….v Introduction …………………………………………………………………………..…1 Chapter I. Female Ontology in the Sacred Texts of Islam ...…………………………...…9 Chapter II. Modern Feminist Objectives …....……………………..………………….20 Chapter III. Traditionalist Critique ……………………………..……………………..28 Chapter IV. Theory vs Practice: Muslim Women’s Networks & Traditional Feminism ……………………...……..…....37 Chapter V. Equality vs Difference: Reflections on Femininity & Masculinity in Islam ...……………………..……………..43 Bibliography …………….…………………………………………………..….……..52 iv Note on Transliteration In this thesis, I have used a simplified Arabic-English transliteration system based on the International Journal of Middle East Studies that excludes most diacritical marks. I do not employ underdots for Arabic consonants or macrons for long vowels. However, I do use the symbol (’) for the medial and final positions of the letter hamza, and the symbol (‘) for the letter ayn. In order to allow Arabic words to be recognized more easily, I have not included assimilation of sun letters after the definite article. I have also standardized several recurring Arabic terms that do not appear in italics after their initial appearance, due to their frequent usage within English academic writing. -

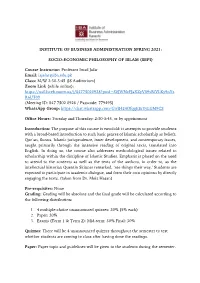

Institute of Business Administration Spring 2021

INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION SPRING 2021: SOCIO-ECONOMIC PHILOSOPHY OF ISLAM (SEPI) Course Instructor: Professor Imad Jafar Email: [email protected] Class: M/W 2:30-3:45 (JS Auditorium) Zoom Link (while online): https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84775020928?pwd=S0JWNzFJaXZyV09vRlVLKy9nYz R6UT09 (Meeting ID: 847 7502 0928 / Passcode: 779495) WhatsApp Group: https://chat.whatsapp.com/GwlI424OfqqEErYyLGM9CS Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday: 2:30-3:45, or by appointment Introduction: The purpose of this course is two-fold: it attempts to provide students with a broad-based introduction to such basic genres of Islamic scholarship as beliefs, Qurʾan, Sunna, Islamic jurisprudence, inner development, and contemporary issues, taught primarily through the intensive reading of original texts, translated into English. In doing so, the course also addresses methodological issues related to scholarship within the discipline of Islamic Studies. Emphasis is placed on the need to attend to the contexts as well as the texts of the authors, in order to, as the intellectual historian Quentin Skinner remarked, ‘see things their way.’ Students are expected to participate in academic dialogue, and form their own opinions by directly engaging the texts. (taken from Dr. Moiz Hasan) Pre-requisites: None Grading: Grading will be absolute and the final grade will be calculated according to the following distribution: 1. 4 multiple-choice unannounced quizzes: 20% (5% each) 2. Paper: 20% 3. Exams (Term 1 & Term 2): Mid-term: 30% Final: 30% Quizzes: There will be 4 unannounced quizzes throughout the semester to test whether students are coming to class after having done the readings. Paper: Paper topic and guidelines will be given to the students during the semester. -

Paradise Lost

Durham E-Theses Tales from the Levant: The Judeo-Arabic Demonic `Other' and John Milton's Paradise Lost AL-AKHRAS, SHARIHAN,SAMEER,ATA How to cite: AL-AKHRAS, SHARIHAN,SAMEER,ATA (2017) Tales from the Levant: The Judeo-Arabic Demonic `Other' and John Milton's Paradise Lost, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12614/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Tales from the Levant: The Judeo-Arabic Demonic ‘Other’ and John Milton’s Paradise Lost By Sharihan Al-Akhras A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of English Studies Durham University 2017 Abstract This thesis revisits Milton’s employment of mythology and the demonic, by shedding a light on a neglected, yet intriguing possible presence of Middle-Eastern mythology – or as identified in this thesis – Judeo-Arabic mythology in Paradise Lost. -

Sunni Myth of Love & Adherence to the Ahlulbayt (As)

Sunni myth of love & adherence to the Ahlulbayt (as) Work file: sunni_myth_of_loving_ahlulbayt.pdf Project: Answering-Ansar.org Articles Revisions: No. Date Author Description Review Info 1.0.0 31.08.2007 Answering-Ansar.org Created 1.0.1 07.09.2007 Answering-Ansar.org Spelling fixes. Copyright © 2002-2007 Answering-Ansar.org. • All Rights Reserved Page 2 of 72 Contents 1.I NTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 3 2.CHAPTER TWO: THE VERDICT OF RASULULLAH (S) WITH REGARDS TO THE L OVERS AND THE ENEMIES OF THE AHL'UL BAYT (AS) ............................................ 4 3.C HAPTER THREE: NASIBISM IN THE ROOTS AHLE SUNNAH .............................. 10 4.C HAPTER FOUR: KHARJISM IN THE ROOTS OF AHLE SUNNAH ......................... 41 5.CHAPTER FIVE: THE BLASPHEMOUS VIEWS OF SOME SUNNI SCHOLARS A BOUT THE IMAMS OF AHLULBAYT [AS] ...................................................................... 52 6.C HAPTER SIX: CONCLUSION .......................................................................................... 69 7.C OPYRIGHT .......................................................................................................................... 72 Copyright © 2002-2007 Answering-Ansar.org. • All Rights Reserved Page 3 of 72 1. Introduction The inspiration behind this article, was not to spread hatred against or belittle the Ahle Sunna, on the contrary we were forced to write it to address the frequent attacks and acerbic remarks by the -

Abul Hasan's Mindset and His Trickery

AAnnsswweerriinngg TThhee LLiieess ooff AAbb uull HHaassaann HHuussssaaiinn AAhhmmeedd GGiibbrriill FFoouuaadd HHaaddddaadd && TThheeiirr MMuuqqaalllliiddeeeenn PPeerrttaaiinniinngg TToo TThhee OOfftt QQuuootteedd NNaarrrraattiioonn ooff AAbbuu AAyyoooobb aall--AAnnssaaaarrii (()) COMPLETE 4 VOLUMES By Abu Hibbaan & Abu Khuzaimah Ansaari www.Ahlulhadeeth.wordpress.com Maktabah Ashaabul Hadeeth & Maktabah Imaam Badee ud deen Sindhee The Weakness of the Narration of Abu Ayoob () 1435H/2014ce Answering The Lies of Abul Hasan Hussain Ahmed, Gibril Fouad Haddad & Their Muqallideen Pertaining To The Oft Quoted Narration of Abu Ayoob al-Ansaari () Complete 4 Volumes 2nd Edn. © Maktabah Ashaabul Hadeeth & Makatabah Imaam Badee ud deen Ramadhaan 1435H / June 2014ce All rights reserved No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced Or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, Now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, without prior Permission from the publishers or authors. Published by In conjunction with www.Ahlulhadeeth.wordpress.com www.ahlulhadeeth.wordpress.com 2 | P a g e Maktabah Ashaabul Hadeeth & Maktabah Imaam Badee ud deen Sindhee The Weakness of the Narration of Abu Ayoob () 1435H/2014ce Answering The Lies of Abul Hasan Hussain Ahmed, Gibril F. Haddad & Their Muqallideen Pertaining to the Oft Quoted Narration of Abu Ayoob al-Ansaari () COMPLETE 4 VOLUMES (In this treatise we have also answered and refuted, Shaikh Zafar Ahmed Uthmaanee Hanafee, Muhammad Alawee al-Malikee Soofee, Mahmood Sa’eed Mamduh Soofee, the lying Soofee Eesaa al-Himyaree, Abu Layth and others. Similarly we have shown the contradictions, inconsistencies and the incongruity of Abul Hasan Hussain Ahmed and Gibril Fouad Haddad from the ink and words of their own Hanafee elders like Shaikh Zafar Ahmed Uthmanee, Shaikh Abdul Fattah Abu Guddah, Shaikh Abdul Hayy Lucknowee, Shaikh Shu’ayb al-Arnaa’oot and their underlings pertaining to Hadeeth and it Sciences. -

Al-Kutub Al-Sittah, the Six Major Hadith Collections

Contents Articles Al-Kutub al-Sittah 1 History of hadith 2 Muhammad al-Bukhari 7 Sahih Muslim 10 Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj Nishapuri 12 Al-Sunan al-Sughra 14 Al-Nasa'i 15 Sunan Abu Dawood 17 Abu Dawood 18 Sunan al-Tirmidhi 19 Tirmidhi 21 Sunan ibn Majah 22 Ibn Majah 23 Muwatta Imam Malik 25 Malik ibn Anas 28 Sunan al-Darimi 31 Al-Darimi 31 Sahih al-Bukhari 33 Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal 36 Ahmad ibn Hanbal 37 Shamaail Tirmidhi 41 Sahih Ibn Khuzaymah 42 Ibn Khuzaymah 43 Sahifah Hammam ibn Munabbih 44 Hammam ibn Munabbih 45 Musannaf ibn Jurayj 46 Musannaf of Abd al-Razzaq 46 ‘Abd ar-Razzaq as-San‘ani 47 Sahih Ibn Hibbaan 48 Al-Mustadrak alaa al-Sahihain 49 Hakim al-Nishaburi 51 A Great Collection of Fabricated Traditions 53 Abu'l-Faraj ibn al-Jawzi 54 Tahdhib al-Athar 60 Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari 61 Riyadh as-Saaliheen 66 Al-Nawawi 68 Masabih al-Sunnah 72 Al-Baghawi 73 Majma al-Zawa'id 74 Ali ibn Abu Bakr al-Haythami 75 Bulugh al-Maram 77 Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani 79 Kanz al-Ummal 81 Ali ibn Abd-al-Malik al-Hindi 83 Minhaj us Sawi 83 Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri 85 Muhammad ibn al Uthaymeen 98 Abd al-Aziz ibn Abd Allah ibn Baaz 102 Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani 107 Ibn Taymiyyah 110 Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya 118 Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab 123 Abdul-Azeez ibn Abdullaah Aal ash-Shaikh 130 Abd ar-Rahman ibn Nasir as-Sa'di 132 Ibn Jurayj 134 Al-Dhahabi 136 Yusuf al-Qaradawi 138 Rashid Rida 155 Muhammad Abduh 157 Jamal-al-Din al-Afghani 160 Al-Suyuti 165 References Article Sources and Contributors 169 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 173 Article Licenses License 174 Al-Kutub al-Sittah 1 Al-Kutub al-Sittah Al-Kutub Al-Sittah) are collections of hadith by Islamic ;ﺍﻟﻜﺘﺐ ﺍﻟﺴﺘﻪ :The six major hadith collections (Arabic scholars who, approximately 200 years after Muhammad's death and by their own initiative, collected "hadith" attributed to Muhammad. -

Answering the Rabid Soofee G F Haddad

Answering the Soofee G. F. Haddad and his book Against Imaam al-Albaanee Compiled by Abu Hibbaan & Abu Khuzaimah Ansaari © 2007 Maktabah Ashaabul Hadeeth, Birmingham UK © 2007 Maktabah Imaam Badee ud deen, Birmingham UK Contents Part 1 The Issue of Calling Oneself Abdul-Mustafa or Abdun-Nabee Part 2 The Issue of Haadhir-Naadhir and Ilm ul-Ghayb According to Abdul- Hayy Lucknowee Hanafee. Part 3 The Fabrication of Kissing the Thumbs In A'dhaan (Updated) Part 4 The Hinduism of the Soofee Bareilwee Religion Part 5 The Fadl al-Rasul al-Badayuni Affair Part 6 The Mulla Saahib Baghadaadee Affair. 2 Introduction All praise be to Allaah Jalo Wa A’la the lord of the creation and of all that exists we praise him seek his aid and assistance, and may there salutations upon the Last and final Messenger of Allaah (Sallalahu Alayhee Was- Sallam) in abundance. Very recently , Gibril Fouad Haddad published a book titled, 'Albani and his freinds', Haddad a rabid soofee has attempted to rebuke and refute the Scholars of Ahlus-Sunnah. To proceed: Without lengthening this introduction and wanting to address the issues and points, it will not be inappropriate to mention some background with regards to this epistle that is to be presented inshallaah. As is well-known ash-Shaikh al-Allaamah Ehsaan Elaahee Zaheer rahimahullah authored a monumental book against the extreme and misguided Soofee sect, the Bareilwee’s. The scholarly level and standard of this book is not hidden from anyone and it is well accepted and acknowledged to be a classical work However in recent times a criminal, an individual upon heretical ways, Gibril Fouad Haddad has attempted to answer this book in a brief manner, but unfortunately has failed miserably and thereby discredited himself and his misguided soofee cult, their methodology aswell as these central issues, it would have been better if he had not undertaken this task thereby preventing the misguidance of others and himself.