Anglican Moral Theology and Ecumenical Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renewing a Catholic Theology of Marriage Through a Common Way of Life: Consonance with Vowed Religious Life-In-Community

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects Renewing a Catholic Theology of Marriage through a Common Way of Life: Consonance with Vowed Religious Life-in-Community Kent Lasnoski Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Lasnoski, Kent, "Renewing a Catholic Theology of Marriage through a Common Way of Life: Consonance with Vowed Religious Life-in-Community" (2011). Dissertations (1934 -). 98. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/98 RENEWING A CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF MARRIAGE THROUGH A COMMON WAY OF LIFE: CONSONANCE WITH VOWED RELIGIOUS LIFE-IN- COMMUNITY by Kent Lasnoski, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABSTRACT RENEWING A CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF MARRIAGE THROUGH A COMMON WAY OF LIFE: CONSONANCE WITH VOWED RELIGIOUS LIFE-IN-COMMUNITY Kent Lasnoski Marquette University, 2011 Beginning with Vatican II‘s call for constant renewal, in light of the council‘s universal call to holiness, I analyze and critique modern theologies of Christian marriage, especially those identifying marriage as a relationship or as practice. Herein, need emerges for a new, ecclesial, trinitarian, and christological paradigm to identify purposes, ends, and goods of Christian marriage. The dissertation‘s body develops the foundation and framework of this new paradigm: a Common Way in Christ. I find this paradigm by putting marriage in dialogue with an ecclesial practice already the subject of rich trinitarian, christological, ecclesial theological development: consecrated religious life. -

First Theology Requirement

FIRST THEOLOGY REQUIREMENT THEO 10001, 20001 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY: BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL **GENERAL DESCRIPTION** This course, prerequisite to all other courses in Theology, offers a critical study of the Bible and the early Catholic traditions. Following an introduction to the Old and New Testament, students follow major post biblical developments in Christian life and worship (e.g. liturgy, theology, doctrine, asceticism), emphasizing the first five centuries. Several short papers, reading assignments and a final examination are required. THEO 20001/01 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL GIFFORD GROBIEN 11:00-12:15 TR THEO 20001/02 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 12:30-1:45 TR THEO 20001/03 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 1:55-2:45 MWF THEO 20001/04 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 9:35-10:25 MWF THEO 20001/05 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 4:30-5:45 MW THEO 20001/06 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 3:00-4:15 MW 1 SECOND THEOLOGY REQUIREMENT Prerequisite Three 3 credits of Theology (10001, 13183, 20001, or 20002) THEO 20103 ONE JESUS & HIS MANY PORTRAITS 9:30-10:45 TR JOHN MEIER XLIST CST 20103 This course explores the many different faith-portraits of Jesus painted by the various books of the New Testament, in other words, the many ways in which and the many emphases with which the story of Jesus is told by different New Testament authors. The class lectures will focus on the formulas of faith composed prior to Paul (A.D. 30-50), the story of Jesus underlying Paul's epistles (A.D. -

Religious Studies 1

Religious Studies 1 teach in the master's program or formally agree to have the M.A. program RELIGIOUS STUDIES director of graduate studies continue as her or his advisor. • Doctor of Philosophy in Theology (p. 1) The Ph.D. program director (or the director's designate) functions as • Master of Arts, Pastoral Ministry (p. 3) the initial academic advisor for all Ph.D. students. The Ph.D. program director assists students in first semester course selection and provides • Master of Arts, Theological Studies (p. 4) initial guidance in scheduling general examinations and selecting the • Certificate, Campus Ministry (p. 4) five members of the general examination committee. The Ph.D. program • Post-Master's Certificate, Campus Ministry (p. 4) director and coordinator of graduate studies report on advising activities • Certificate, Pastoral Care (p. 5) for each student to the Ph.D. committee once per semester. Marian Studies Doctoral students also work with a five-member general examination committee. The committee must include a faculty member from each of The International Marian Research Institute (IMRI) is no longer offering the core disciplines: history of Christianity, biblical studies, and theology/ graduate degrees and is in the process of transitioning to its new home in ethics. The committee determines whether the student passes or fails the the College of Arts and Sciences. The Department of Religious Studies is three general examinations. developing Marian course offerings in connection with IMRI's transition, and plans to offer certificates at the undergraduate and graduate As soon as doctoral students determine their dissertation topics, levels. Please contact Jana Bennett, Department Chairperson, for more they should choose, in consultation with the Ph.D. -

'It Is Bread and It Is Christ's Body Too': Presence and Sacrifice in The

‘It is Bread and it is Christ’s Body Too’: Presence and Sacrifice in the Eucharistic Theology of Jeremy Taylor Paul Andrew Barlow PhD, MA, BSc, PGCE A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dublin City University Supervisor: Dr Joseph Rivera School of Theology, Philosophy and Music July 2019 ii I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ID No.:15212014 Date: 15th July 2019 iii iv And yet if men would but do reason, there were in all religion no article which might more easily excuse us from meddling with questions about it than this of the holy sacrament. For as the man in Phaedrus that being asked what he carried hidden under his cloak, answered, it was hidden under his cloak; meaning that he would not have hidden it but that he intended it should be secret; so we may say in this mystery to them that curiously ask what or how it is, mysterium est, ‘it is a sacrament and a mystery;’ by sensible instruments it consigns spiritual graces, by the creatures it brings us to God, by the body it ministers to the Spirit. -

Jesus' Prohibition of Anger

Theological Studies 68 (2007) JESUS’ PROHIBITION OF ANGER (MT 5:22): THE PERSON/SIN DISTINCTION FROM AUGUSTINE TO AQUINAS WILLIAM C. MATTISON III Christian reflection on the morality of anger must address Jesus’ words in Matthew 5:22: “whoever is angry with his brother will be liable to judgment.” One interpretation of this passage found in the Christian tradition relies on what is called here the “person/sin dis- tinction”: anger at persons is sinful, while anger at sin is permissible. The article traces this distinction’s use from Augustine to Aquinas, both to display a living textual tradition at work and to contribute to the broader question of the possibility of virtuous Christian anger. ESUS’ WORDS IN MATTHEW 5:22, “whoever is angry with his brother will J be liable to judgment,” appear unequivocal.1 Anger should have no place in the Christian life. Yet a survey of thinkers in the Christian tradition WILLIAM C. MATTISON III received his Ph.D. in moral theology and Christian ethics from the University of Notre Dame and is now assistant professor of theol- ogy at the Catholic University of America. His areas of expertise are fundamental moral theology, the moral theology of Thomas Aquinas, virtue ethics, and mar- riage. He has edited New Wine, New Wineskins: A Next Generation Reflects on Key Issues in Catholic Moral Theology (2005). Among his most recent published essays are: “The Changing Face of Natural Law: The Necessity of Belief for Natural Law Norm Specification,” Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics 27 (2007); “Marriage and Sexuality, Eschatology, and the Nuptial Meaning of the Body in Pope John Paul II’s Theology of the Body,” in Sexuality and the U.S. -

A Report of the House of Bishops' Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church Ho

Women Bishops in the Church of England? A report of the House of Bishops’ Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church House Publishing Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3NZ Tel: 020 7898 1451 Fax: 020 7989 1449 ISBN 0 7151 4037 X GS 1557 Printed in England by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Published 2004 for the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England by Church House Publishing. Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2004 Index copyright © Meg Davies 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought from the Copyright Administrator, The Archbishops’ Council, Church of England, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3NZ. Email: [email protected]. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Contents Membership of the Working Party vii Prefaceix Foreword by the Chair of the Working Party xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Episcopacy in the Church of England 8 3. How should we approach the issue of whether women 66 should be ordained as bishops? 4. The development of women’s ministry 114 in the Church of England 5. Can it be right in principle for women to be consecrated as 136 bishops in the Church of England? 6. -

What Sin?? John F

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 43 | Number 3 Article 7 August 1976 Hate the Sin But Love the Sinner. Sin? What Sin?? John F. Russell Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Recommended Citation Russell, John F. (1976) "Hate the Sin But Love the Sinner. Sin? What Sin??," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 43: No. 3, Article 7. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol43/iss3/7 Hate the Sin But Love the Sinner. Sin? What Sin?? John F. Russell, J.D. (This is a greatly abbreviated theologians and others who have adaptation from a chapter in Dr. expressed their scholarly and oth Russell's cur r e n t book-length erwise knowledgeable views on manuscript on the homosexual the matter and the impact that issue in all the major religious de the various avenues of approach nominations in the United States. will have on church, society, and In gathering material for the especially the individual.) book, Dr. Russell, who has been The N ew Catholic Encyclope a professional scholar on organ dia describes the homosexual act ized homosexual activities for as a "grave transgression of the over two decades, has interviewed divine will." literally hundreds of religious and lay officials of all denominations Right? along with numerous gay activ The National Conference of ists. In addition, he has re Catholic B ish 0 p s , speaking searched well over 10,000 articles, through its Principles to Guide publications, and news items on Confessors in Questions of Homo the subject. The material present sexuality, says that homosexual ed here barely penetrates even practices are a "grave violation of this single aspect of the multi the law of God." fac eted scope of the total problem realized by the religious and lay Right? communities, homosexual and And the most recent expression heterosexual alike. -

Development of Catholic Moral Doctrine: Probing the Subtext M

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers January 2003 Development of Catholic Moral Doctrine: Probing the Subtext M. Cathleen Kaveny Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation M. Cathleen Kaveny. "Development of Catholic Moral Doctrine: Probing the Subtext." University of St. Thomas Law Journal 1, no.1 (2003): 234-252. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE DEVELOPMENT OF CATHOLIC MORAL DOCTRINE: PROBING THE SUBTEXT M. CATHLEEN KAVENY* I. INTRODUCTION Judge Noonan has been speaking and writing explicitly about the gen- eral topic of development of doctrine in Catholic moral theology for ap- proximately a decade now. In 1993, he published a now-classic article on the topic in Theological Studies, arguably the most prominent journal of Catholic theology in the United States.' He gave a plenary address on de- velopment of moral doctrine to the annual meeting of the Catholic Theolog- ical Society of America in 1999.2 Judge Noonan developed his arguments and analyses more extensively in the fall of 2003, when he delivered a se- ries of eight Erasmus Lectures at the University of Notre Dame on the de- velopment of moral doctrine. -

The Task Ahead for the Theologian in a New Decade

THE TASK AHEAD FOR THE THEOLOGIAN IN A NEW DECADE The task which today confronts those Catholics who are vitally interested in the science of theology is both formidable and stimu- lating. I refer not so much to the challenge which arises from the hostility of those elements in a materialistic and secularistic culture that doubt or deny or scoff at God, and hence have nothing but scorn for a science whose total object is God and creatures in their relationship to God.1 Rather am I concerned with the challenge that theology itself—in the midst of a milieu which the remarkable ad- vance of knowledge is changing with almost incredible rapidity— presents to the theologian in diverse and manifold forms, as a living science, in this year of Our Lord 1960. The observations in this address, which I am highly privileged to deliver as your president, are in no way intended to be compre- hensive or exhaustive. Surely they make no pretense to solve any profound theological problem. I will consider them to be in some small degree successful, if they contribute something toward bring- ing into focus the nature and the imperiousness of the challenge. Time and again within the past few years our attention has been called to the need of fostering and furthering a greater interest in and love for things intellectual. And rightly so. But may I suggest here that there is no less need of what may be called a personal predisposition or orientation on the part of scholars, without which there can be no true scholarship in any field, theology included: a predisposition or orientation deriving from and indeed constituted by the possession of varied intellectual characteristics, but espe- cially of maturity of approach, impartiality of attitude, and respect for truth. -

Another Anglican View 11 C

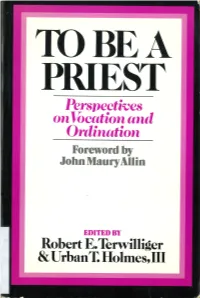

TO BE A PRIEST Perspectives on Vocation and Ordination edited by RaBERT E. TERWILLIGER URBAN T. HOLMES, ItrI with a Foreword by John Maury Allin A Crossroad Book THE SEABURY PRESS O NEW YORK The Seabury Press 815 Second Avenue New York, N.Y. 10017 Copyright O 1975 by The Seabury Press, Inc. Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations in critical reviews and articles. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CÄTALOGING IN PUBLIC.A,TION DAT.A Main entry under title: To be a priest. "A Crossroad book." Bibliography: p. 1. Priests-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Priesthood-Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Ter- wilÌiger, Robert E. II. Holmes, Urban Tigner, 1930- 8V662.T6 262'.r4 75-28248 ISBN 0-8164-2592-2 contents FOREWORD John Maurg AIIín rx c. PREFACE Robert E. Teruillíger and Urban T' Holmes be reproduced in any manner whatsoever ter, except for brief quotations in cri;ic; Pørt L What ís a Príest? 1. One Anglican View Robert E. TerwíIlíger 2. Another Anglican View 11 C. FitøSímons AIIíson 3. An Orthodox Statement 2L Thomas HoPko 4. A Roman Catholic Catechism 29 Quentín Quesnell Pørt IL The Príesthood ín the Bíble ønd Hístory 5. Priesthood in the History of Religions 45 loseph Kítagaua 6. The Priesthood of Christ 55 MEIes M' Bourke 7. Priesthood in the New Testament 63 ,UBLICATION DATA Louís Weil 8. Presbyters in the EarlY Church 7L MasseE H. ShePherd, Jr' 9. -

Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667,) Bishop of Down and Connor

Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667,) Bishop of Down and Connor. Jeremy Taylor graduate d from Cambridge University in 1626. He was under the patronage of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, through whose influence he became chaplain to King Charles I. He held a fellowship at Al l Souls, Oxford for two years before being called to Uppingham in Rutland and later Overstone, Northamptonshire. His first wife, by whom he had six children, died in 1651; his second wife was believed to be the natural daughter of King Charles I. Jeremy Taylor the Writer Jeremy Taylor was sometimes In 1645 Archbishop Laud was tried and executed for known as “the Shakespeare of treason by the Puritan Parliament. Taylor’s relationship with the Divines” because of the Laud, and his Royalist leanings, led to three brief periods of poetic expression of his prose. imprisonment after Parliament’s victory over the King. Curiously, he gained fame as an author under the “Taylor became one of the most Protectorate of the Puritan Oliver Cromwell. learned scholars and most distinguished writers in a great During a period of retirement in Wales, he became the literary age.” Gilbert Highet, The private chaplain of the Earl of Carbery. After the Restoration, Classical Tradition. he was made bishop of Down and Connor in Ireland, where he was also made vice-chancellor of the University of Dublin James Boswell recommended of which he wrote: “I found all things in a perfect disorder . Taylor’s works to Dr. Samuel Johnson “at times when he was a heap of men and boys, but no body of a college, no one most distressed.” member, either fellow or scholar, having any legal title to his place, but thrust in by tyranny or chance.” He developed and enforced regulations and established lectureships. -

Salvation in Christ.Qxp 4/29/2005 4:08 PM Page 53

Salvation in Christ.qxp 4/29/2005 4:08 PM Page 53 Anglican Soteriology: Incarnation, Worship, and the Property of Mercy Douglas J. Davies Douglas J. Davies is a professor of religion in the Department of Theology, University of Durham, England. he birth of Anglicanism can be told with many tongues and motives. Kingly lust, political independence, the love of pure doctrine, martyred saints and scholars, and the free- Tdom of a new vernacular liturgy all play their part in the emergence of Anglicanism as a Protestant form of Catholic Chris- tianity. Anglicanism is marked less by doctrinal innovation, over sal- vation at least, than by its choice and complementarity of doctrine and practice. The task of writing on salvation in Anglicanism is not easy. For example, we might agree with Stephen Neill’s classic study whose fif- teenth and final chapter observed that no “special section” was devoted to Anglican theology precisely because “there is no particular Anglican theology.” He rehearses the importance of the Catholic Faith, of the Holy Scriptures, of the Creeds and first four General Councils of the undivided Church as furnishing everything that is “necessary to 53 Salvation in Christ.qxp 4/29/2005 4:08 PM Page 54 Salvation in Christ salvation.”1 He also highlights a certain “Anglican attitude and an Angli- can atmosphere” that “defies analysis” and must be “felt and experienced in order to be understood.”2 While he further lists episcopacy, learning, continuity with the past, and tolerance as additional Anglican features, Neill emphasizes