Climbs and Expeditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Department of the Interior Reports of The

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REPORTS OF THE ALASKA DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL AND GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS AND PREDECESSOR AGENCIES, 1913-1973, INDEXED BY QUmRANGLE BY Edward H. Cobb Open-f ile report 74- 209 1974 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Geological Survey standards NOTE NOTE NOTE Since this index was prepared 18 open-file reports of the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys have been withdrawn, consolidated, revised, or assigned different numbers. References to these reposts should be deleted from thes index. The report numbers are: 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 39, and 40. They are listed under the following quadrangles: Afognak Mar shall Ambler Mves McCarthy Anchorage Medf ra Baird Inlet Mt. Fairweather Bendeleben Mt. St. Elias Bering Glacier Nabesna Bethel Nunivak Island Big Delta Port Moller Cape Mendenhall Rubs Charley River St. Michael Chignik Sitka Coxdova Survey Pass Eagle Sutwik Island Hooper Bay Talkeetna ICY BY Talkeetna Mountains ILiamna Trinity Islands Kaguyak Tyonek Karluk Ugashik Kodiak Valde z Kwiguk Yakutat Contents Page Introduction ......................................................... Alaska - General ..................................................... Quadrangle index ..................................................... Adak quadrarLgle ................................................. Afognak quadrangle .............................................. Ambler River quadrangle ........................................ -

Los Cien Montes Más Prominentes Del Planeta D

LOS CIEN MONTES MÁS PROMINENTES DEL PLANETA D. Metzler, E. Jurgalski, J. de Ferranti, A. Maizlish Nº Nombre Alt. Prom. Situación Lat. Long. Collado de referencia Alt. Lat. Long. 1 MOUNT EVEREST 8848 8848 Nepal/Tibet (China) 27°59'18" 86°55'27" 0 2 ACONCAGUA 6962 6962 Argentina -32°39'12" -70°00'39" 0 3 DENALI / MOUNT McKINLEY 6194 6144 Alaska (USA) 63°04'12" -151°00'15" SSW of Rivas (Nicaragua) 50 11°23'03" -85°51'11" 4 KILIMANJARO (KIBO) 5895 5885 Tanzania -3°04'33" 37°21'06" near Suez Canal 10 30°33'21" 32°07'04" 5 COLON/BOLIVAR * 5775 5584 Colombia 10°50'21" -73°41'09" local 191 10°43'51" -72°57'37" 6 MOUNT LOGAN 5959 5250 Yukon (Canada) 60°34'00" -140°24’14“ Mentasta Pass 709 62°55'19" -143°40’08“ 7 PICO DE ORIZABA / CITLALTÉPETL 5636 4922 Mexico 19°01'48" -97°16'15" Champagne Pass 714 60°47'26" -136°25'15" 8 VINSON MASSIF 4892 4892 Antarctica -78°31’32“ -85°37’02“ 0 New Guinea (Indonesia, Irian 9 PUNCAK JAYA / CARSTENSZ PYRAMID 4884 4884 -4°03'48" 137°11'09" 0 Jaya) 10 EL'BRUS 5642 4741 Russia 43°21'12" 42°26'21" West Pakistan 901 26°33'39" 63°39'17" 11 MONT BLANC 4808 4695 France 45°49'57" 06°51'52" near Ozero Kubenskoye 113 60°42'12" c.37°07'46" 12 DAMAVAND 5610 4667 Iran 35°57'18" 52°06'36" South of Kaukasus 943 42°01'27" 43°29'54" 13 KLYUCHEVSKAYA 4750 4649 Kamchatka (Russia) 56°03'15" 160°38'27" 101 60°23'27" 163°53'09" 14 NANGA PARBAT 8125 4608 Pakistan 35°14'21" 74°35'27" Zoji La 3517 34°16'39" 75°28'16" 15 MAUNA KEA 4205 4205 Hawaii (USA) 19°49'14" -155°28’05“ 0 16 JENGISH CHOKUSU 7435 4144 Kyrghysztan/China 42°02'15" 80°07'30" -

Geologic Maps of the Eastern Alaska Range, Alaska, (44 Quadrangles, 1:63360 Scale)

Report of Investigations 2015-6 GEOLOGIC MAPS OF THE EASTERN ALASKA RANGE, ALASKA, (44 quadrangles, 1:63,360 scale) descriptions and interpretations of map units by Warren J. Nokleberg, John N. Aleinikoff, Gerard C. Bond, Oscar J. Ferrians, Jr., Paige L. Herzon, Ian M. Lange, Ronny T. Miyaoka, Donald H. Richter, Carl E. Schwab, Steven R. Silva, Thomas E. Smith, and Richard E. Zehner Southeastern Tanana Basin Southern Yukon–Tanana Upland and Terrane Delta River Granite Jarvis Mountain Aurora Peak Creek Terrane Hines Creek Fault Black Rapids Glacier Jarvis Creek Glacier Subterrane - Southern Yukon–Tanana Terrane Windy Terrane Denali Denali Fault Fault East Susitna Canwell Batholith Glacier Maclaren Glacier McCallum Creek- Metamorhic Belt Meteor Peak Slate Creek Thrust Broxson Gulch Fault Thrust Rainbow Mountain Slana River Subterrane, Wrangellia Terrane Phelan Delta Creek River Highway Slana River Subterrane, Wrangellia Terrane Published by STATE OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL & GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS 2015 GEOLOGIC MAPS OF THE EASTERN ALASKA RANGE, ALASKA, (44 quadrangles, 1:63,360 scale) descriptions and interpretations of map units Warren J. Nokleberg, John N. Aleinikoff, Gerard C. Bond, Oscar J. Ferrians, Jr., Paige L. Herzon, Ian M. Lange, Ronny T. Miyaoka, Donald H. Richter, Carl E. Schwab, Steven R. Silva, Thomas E. Smith, and Richard E. Zehner COVER: View toward the north across the eastern Alaska Range and into the southern Yukon–Tanana Upland highlighting geologic, structural, and geomorphic features. View is across the central Mount Hayes Quadrangle and is centered on the Delta River, Richardson Highway, and Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS). Major geologic features, from south to north, are: (1) the Slana River Subterrane, Wrangellia Terrane; (2) the Maclaren Terrane containing the Maclaren Glacier Metamorphic Belt to the south and the East Susitna Batholith to the north; (3) the Windy Terrane; (4) the Aurora Peak Terrane; and (5) the Jarvis Creek Glacier Subterrane of the Yukon–Tanana Terrane. -

Club Activities

Club Activities EDITEDBY FREDERICKO.JOHNSON A.A.C.. Cascade Section. The Cascade Section had an active year in 1979. Our Activities Committee organized a slide show by the well- known British climber Chris Bonington with over 700 people attending. A scheduled slide and movie presentation by Austrian Peter Habeler unfortunately was cancelled at the last minute owing to his illness. On-going activities during the spring included a continuation of the plan to replace old bolt belay and rappel anchors at Peshastin Pinnacles with new heavy-duty bolts. Peshastin Pinnacles is one of Washington’s best high-angle rock climbing areas and is used heavily in the spring and fall by climbers from the northwestern United States and Canada. Other spring activities included a pot-luck dinner and slides of the American Women’s Himalayan Expedition to Annapurna I by Joan Firey. In November Steve Swenson presented slides of his ascents of the Aiguille du Triolet, Les Droites, and the Grandes Jorasses in the Alps. At the annual banquet on December 7 special recognition was given to sec- tion members Jim Henriot, Lynn Buchanan, Ruth Mendenhall, Howard Stansbury, and Sean Rice for their contributions of time and energy to Club endeavors. The new chairman, John Mendenhall, was introduced, and a program of slides of the alpine-style ascent of Nuptse in the Nepal Himalaya was presented by Georges Bettembourg, followed by the film, Free Climb. Over 90 members and guests were in attendance. The Cascade Section Endowment Fund Committee succeeded in raising more than $5000 during 1979, to bring total donations to more than $12,000 with 42% of the members participating. -

High Resolution Adobe PDF

115°20'0"W 115°0'0"W 114°40'0"W 114°20'0"W PISTOL LAKE " CHINOOK MOUNTAIN ARTILLERY DOME SLIDEROCK RIDGE FALCONBERRY PEAK ROCK CREEK SHELDON PEAK Red Butte "Grouse Creek Peak WHITE GOAWTh iMte OVaUlleNyT MAoIuNntain LITTLE SOLDIER MOUNTAIN N FD " N FD 6 8 8 T d Parker Mountain 6 Greyhound Mountain r R a k i e " " 5 2 l e 0 1 0 r 0 0 il 1 C l i a 1 n r o Big Soldier Mountain a o e pi r n Morehead Mountain T Pinyon Peak L White MoSunletain g Deer Rd " T " HONEYMOON LAKE " " BIG SOLDIER MOUNTAIN SOLDIER CREEK GREYHOUND MOUNTAIN PINYON PEAK CASTO SHERMAN PEAK CHALLIS CREEK LAKES TWIN PEAKS PATS CREEK Lo FRANK CHURCH - RIVER OF NO RETURN WILDERNESS o n Sherman Peak C Mayfield Peak Corkscrew Mountain r " d e " " R ek ls R l d a Mosquito Flat Reservoir F r e Langer Peak rl g T g k a Ruffneck Peak " ac d D P R d " k R Blue Bunch Mo"untain d e M e k R ill C r e Bear Valley Mountain k e e htmile r " e ig C r E C en r C re d ave Estes Mountain e G ar B e k " R BLUE BUNCH MOUNTAIN d CAPE HORN LAKES LANGER PEAK KNAPP LAKES MOUNT JORDAN l Forest CUSTER ELEVENMILE CREEK BAYHORRSaEm sLhAorKn EMountaiBn AYHORSE Nat De Rd Keysto"ne Mountain velop Road 579 d R " Cabin Creek Peak Red Mountain rk Cape Horn MounCtaaipne Horn Lake #1 o Bay d " Bald Mountain F hors R " " e e Cr 2 d e eek 8 R " nk Rd 5 in Ya d a a nt o ou Lucky B R S A L M O N - C H A L L I S N Fo S p M y o 1 C d Bachelor Mountain R q l " u e 2 5 a e d v y 19 p R Bonanza Peak a B"ald Mountain e d e w Nf 045 D w R R N t " s H s H C d " e sf r e o Basin Butte r 0 t U ' o r e F a n e 0 l t 21 t -

Alaska Range

Alaska Range Introduction The heavily glacierized Alaska Range consists of a number of adjacent and discrete mountain ranges that extend in an arc more than 750 km long (figs. 1, 381). From east to west, named ranges include the Nutzotin, Mentas- ta, Amphitheater, Clearwater, Tokosha, Kichatna, Teocalli, Tordrillo, Terra Cotta, and Revelation Mountains. This arcuate mountain massif spans the area from the White River, just east of the Canadian Border, to Merrill Pass on the western side of Cook Inlet southwest of Anchorage. Many of the indi- Figure 381.—Index map of vidual ranges support glaciers. The total glacier area of the Alaska Range is the Alaska Range showing 2 approximately 13,900 km (Post and Meier, 1980, p. 45). Its several thousand the glacierized areas. Index glaciers range in size from tiny unnamed cirque glaciers with areas of less map modified from Field than 1 km2 to very large valley glaciers with lengths up to 76 km (Denton (1975a). Figure 382.—Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the Alaska Range in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image mosaic from Mike Fleming, Alaska Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Anchorage, Alaska. The numbers 1–5 indicate the seg- ments of the Alaska Range discussed in the text. K406 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD and Field, 1975a, p. 575) and areas of greater than 500 km2. Alaska Range glaciers extend in elevation from above 6,000 m, near the summit of Mount McKinley, to slightly more than 100 m above sea level at Capps and Triumvi- rate Glaciers in the southwestern part of the range. -

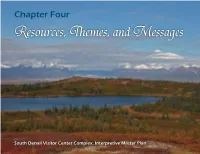

Chapter Four

Chapter Four South Denali Visitor Center Complex: Interpretive Master Plan Site Resources Tangible Natural Site Features 1. Granite outcroppings and erratic Resources are at the core of an boulders (glacial striations) interpretive experience. Tangible resources, those things that can be seen 2. Panoramic views of surrounding or touched, are important for connecting landscape visitors physically to a unique site. • Peaks of the Alaska Range Intangible resources, such as concepts, (include Denali/Mt. McKinley, values, and events, facilitate emotional Mt. Foraker, Mt. Hunter, Mt. and meaningful experiences for visitors. Huntington, Mt. Dickey, Moose’s Effective interpretation occurs when Erratic boulders on Curry Ridge. September, 2007 Tooth, Broken Tooth, Tokosha tangible resources are connected with Mountains) intangible meanings. • Peters Hills • Talkeetna Mountains The visitor center site on Curry Ridge maximizes access to resources that serve • Braided Chulitna River and valley as tangible connections to the natural and • Ruth Glacier cultural history of the region. • Curry Ridge The stunning views from the visitor center site reveal a plethora of tangible Mt. McKinley/Denali features that can be interpreted. This Mt. Foraker Mt. Hunter Moose’s Tooth shot from Google Earth shows some of the major ones. Tokosha Ruth Glacier Mountains Chulitna River Parks Highway Page 22 3. Diversity of habitats and uniquely 5. Unfettered views of the open sky adapted vegetation • Aurora Borealis/Northern Lights • Lake 1787 (alpine lake) • Storms, clouds, and other weather • Alpine Tundra (specially adapted patterns plants, stunted trees) • Sun halos and sun dogs • High Brush (scrub/shrub) • Spruce Forests • Numerous beaver ponds and streams Tangible Cultural Site Features • Sedge meadows and muskegs 1. -

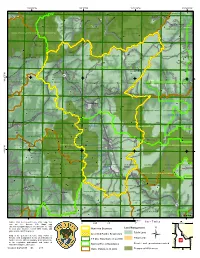

1:100,000 1 Inch = 1.6 Miles Central Idaho-01

R 10 E R 11 E 115°7'30"W R 12 E 115°W R 13 E 114°52'30"W R 14 E 114°45'W R 15 E 114°37'30"W R 16 E 114°30'W R 17 E 114°22'30"W R 18 E S k i k e l v e Joe Jump Basin e Lookout Mountain k La e e r st e r r k C k e R C e h ee r C e e Little a Cr u Iron Cre k nce C l h r w Airport Rd e Car c C Central Idaho-01 e bo n an k B liv o t C nat e l e d e r u k i a r C e a g l C e F S r r e e e e S e C a M M C k e t s r a k o in a C a G o Creek s th rc in k i o m o e C Fire Suppression Constraints e S re C r k y e r k e e C m re e ek n m C e k i r r Alpine Peak o Ziegler Basin t Fish Critical Habitats T 10 N a C Observation Peak J e an s B g je T 10 N n d i Jimmy Smith Lake n v i ulch Bull Trout Critical Habitat a G r Hoodoo Lake L k rry k Creek ake Cree he G Big L Big Lake Creek 222 e Lake C Grandjean e Big Balsam Rd r k Trailer Lakes Regan, Mount C e Spawning Areas of Concern Little Redfish Lake e ry r S a C ek 222 F re Trail Creek Lakes d o o C n c rk l u r Resource Avoidance Area 36 P i 36 o a ra Big Lake Creek a Williams Peak B M ye T NF-214 Rd tte 31 31 36 31 31 36 31 Ri Cleveland Creek Safety Concerns ve 36 Wapiti Creek Rd r EAST FORK 36 S a l Suppression tactics Avoidance Area 01 Thompson Peak m o Railroad Ridge n Crater Lake 06 01 R Bluett Creek D Misc Resource Areas i ry 06 01 k v 01 01 06 06 Gu 01 06 k e e lc e re h e C r k r k k e Meadows, The C e oo re Watson Peak im Creek x Wilderness Area e hh C Iron Basin J o r Fis old Chinese Wall ek F C G re ti C Bluett Creek i Slate Creek r Retardant Avoidance Area p Gunsight Lake e a ld W ou B -

Longs Peak, the Diamond. in August, 1960, Two Californians, Bob Kamps and Dave Rearick, Made the First Ascent of the Diamond ( A.A.J ., 1961, 12:2, Pp

Longs Peak, The Diamond. In August, 1960, two Californians, Bob Kamps and Dave Rearick, made the first ascent of the Diamond ( A.A.J ., 1961, 12:2, pp. 297-301.) Their route goes straight up the center of the 1000-foot face. Two years later Layton Kor and Charles Roskosz, both of Colorado, completed a new route, “The Yellow W all” , about 100 yards left of the Kamps-Rearick route. Though on less steep and better rock, the Yellow Wall is more circuitous and has a harder aid pitch. On July 13, after making the second ascent of the original route, Kor and I established a new one, “The Jack of Diamonds” . The “Jack” stands just right of the Kamps-Rearick, and like that route, has a rotten section which overhangs for 400 feet. Although the nailing is slightly easier on the Jack, the free climbing is more difficult than either of the other two routes. The night before the ascent, we bivouacked on Broadway, a huge ledge at the base of the Diamond. Kor slept placidly, but next day all his famous energy and drive became focused upon the problem of getting up this new route. The day dawned with the sun shining warmly through a clear blue sky, but by noon clouds had gathered and a strong wind numbed our fingers. The weather worsened as we climbed higher, and in the afternoon snow flurries swirled around us. Nearing the top, we fought an insidious exhaustion caused by altitude, cold, and our daylong struggle. Racing against the setting sun to avoid a bad night in slings, Kor led the last pitch, a long, strenuous jam-crack. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

T H E D a V I E R E C O

The D avie Record DAVIE COUNTY’S OLDEST NEWSPAPER-THE PAPER THE PEOPDE READ mHERE SHALL THE PEv-SS. THE PEOPLE’S RIGHTS MAINTAIN: UNAWED BY INFLUENCE AND UNBRIBED BY GAIN.” I VOLUMN XLVIII. MOCKSVILLE. NORTH CAROLINA, WEDNESDAY, IULY 2 . 194 7 . NUM BER 5 0 NEW SOF LONG AGO. Let Us Do Good John Public Is Fair OPA Fades Out Congress Represents Seen Along Main Street Rev. Walter E. Isenhour. Hiddenite. N. C. Worried a bit by all the charges The much “cussed and discuss, The People By The Street Rambler. V bat Va* Happening In Dayie It should be the sincere desire of being bruited about anentthe “ex ed” Office of Price Aoministration 000000 Recently tbe governors of most Before The New Deal Used Up all mankind to do good. This is orbitant” profits of retailers et a I in finally passed out of the picture on One-horse covered wagon slow of tbe Far Western States met and God’s will tor us, and when we do this hevday of high prices a Ten Saturday, May 31, So -ended quiet ly wending its wav across the The Alphabet, Drowned The jointly denounced the ac ion of the His will He alwavs blesses ns in a nessee grocer has hit upon a novel ly a government bureau which has square—Seven young ladies and House in heavily reducing appro Hogs and Plowed Up The wonderful way, Ottr blessed Lord, scheme. cansed more controversy than anv one young man sitting in parked priations for the Reclamation Bu Cotton and Corn. -

2016 Annual Mountaineering Summary

2016 Annual Mountaineering Summary Photo courlesy of Menno Boermans 2016 Statistical Year in Review Each season's !!!~~D.~~.iD.~.~- ~!~~ . !:~':!.!~ . ~!~!!~!!~~ · including total attempts and total summits for Denali and Foraker, are now compiled into one spreadsheet spanning from 1979 to 2016. For a more detailed look at 2016, you can find the day to-day statistics, weather, and conditions reports discussed in the !?.~.':1.~.1.i __ g!~P.~!~~~~ blog. Quick Facts-Denali • Climbers from the USA: 677 (60% of total) Top states represented were Alaska (122), Washington (103), Colorado (95), and California (64) • International climbers: 449 (40% of total) Foreign countries with the most climbers were the United Kingdom (52) Japan (39), France (28). In a three-way tie for fouth position were the Czech Republic, Korea, and Poland, each with 23 climbers. Nepal was close behind with 22. Of the less-represented countries, we welcomed just one climber each from Montenegro, Iceland, Mongolia, and Croatia. • Average trip length Overall average was 16.5 days, start to finish. • Average age 39 years old • Women climbers Comprised 12% of total (132 women). The summit rate for women was 59%. • Summits by month • May: 112 • June:514 • July: 44 • Busiest Summit Days • June 16: 83 summits • June 23: 71 summits • June 1: 66 summits • May 31: 35 summits 2016 Search and Rescue Summary Avalanche Hazard A winter climber departed Talkeetna on January 21, 2016 for a planned 65-day solo expedition on the West Ridge of Mount Hunter. On April 3 (Day 72 of the expedition), the uninjured soloist was evacuated from 8,600 feet via short-haul rescue basket after becoming stranded with inadequate food and fuel due to persistent avalanche conditions.