Bartók's Polymodality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg

Ryan Weber: Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg Grieg‘s intriguing statement, ―the realm of harmonies has always been my dream world,‖1 suggests the rather imaginative disposition that he held toward the roles of harmonic function within a diatonic pitch space. A great degree of his chromatic language is manifested in subtle interactions between different pitch spaces along the dualistic lines to which he referred in his personal commentary. Indeed, Grieg‘s distinctive style reaches beyond common-practice tonality in ways other than modality. Although his music uses a variety of common nineteenth- century harmonic devices, his synthesis of modal elements within a diatonic or chromatic framework often leans toward an aesthetic of Impressionism. This multifarious language is most clearly evident in the composer‘s abundant songs that span his entire career. Setting texts by a host of different poets, Grieg develops an approach to chromaticism that reflects the Romantic themes of death and despair. There are two techniques that serve to characterize aspects of his multi-faceted harmonic language. The first, what I designate ―chromatic juxtapositioning,‖ entails the insertion of highly chromatic material within ^ a principally diatonic passage. The second technique involves the use of b7 (bVII) as a particular type of harmonic juxtapositioning, for the flatted-seventh scale-degree serves as a congruent agent among the realms of diatonicism, chromaticism, and modality while also serving as a marker of death and despair. Through these techniques, Grieg creates a style that elevates the works of geographically linked poets by capitalizing on the Romantic/nationalistic themes. -

The Rosenwinkel Introductions

The Rosenwinkel Introductions: Stylistic Tendencies in 10 Introductions Recorded by Jazz Guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel Jens Hoppe A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I, Jens Hoppe, hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person except where acknowledged in the text. This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of a higher degree. Signed: ______________________________________________Date: 31 March 2016 i Acknowledgments The task of writing a thesis is often made more challenging by life’s unexpected events. In the case of this thesis, it was burglary, relocation, serious injury, marriage, and a death in the family. Disruptions also put extra demands on those surrounding the writer. I extend my deepest gratitude to the following people for, above all, their patience and support. To my supervisor Phil Slater without whom this thesis would not have been possible – for his patience, constructive comments, and ability to say things that needed to be said in a positive and encouraging way. Thank you Phil. To Matt McMahon, who is always an inspiration, whether in conversation or in performance. To Simon Barker, for challenging some fundamental assumptions and talking about things that made me think. To Troy Lever, Abel Cross, and Pete ‘Göfren’ for their help in the early stages. They are not just wonderful musicians and friends, but exemplary human beings. To Fletcher and Felix for their boundless enthusiasm, unconditional love and the comic relief they provided. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Diatonic-Collection Disruption in the Melodic Material of Alban Berg‟S Op

Michael Schnitzius Diatonic-Collection Disruption in the Melodic Material of Alban Berg‟s Op. 5, no. 2 The pre-serial Expressionist music of the early twentieth century composed by Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils, most notably Alban Berg and Anton Webern, has famously provoked many music-analytical dilemmas that have, themselves, spawned a wide array of new analytical approaches over the last hundred years. Schoenberg‟s own published contributions to the analytical understanding of this cryptic musical style are often vague, at best, and tend to describe musical effects without clearly explaining the means used to create them. His concept of “the emancipation of the dissonance” has become a well known musical idea, and, as Schoenberg describes the pre-serial music of his school, “a style based on [the premise of „the emancipation of the dissonance‟] treats dissonances like consonances and renounces a tonal center.”1 The free treatment of dissonance and the renunciation of a tonal center are musical effects that are simple to observe in the pre-serial music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, and yet the specific means employed in this repertoire for avoiding the establishment of a perceived tonal center are difficult to describe. Both Allen Forte‟s “Pitch-Class Set Theory” and the more recent approach of Joseph Straus‟s “Atonal Voice Leading” provide excellently specific means of describing the relationships of segmented musical ideas with one another. However, the question remains: why are these segmented ideas the types of musical ideas that the composer wanted to use, and what role do they play in renouncing a tonal center? Furthermore, how does the renunciation of a tonal center contribute to the positive construction of the musical language, if at all? 1 Arnold Schoenberg, “Composition with Twelve Tones” (delivered as a lecture at the University of California at Las Angeles, March 26, 1941), in Style and Idea, ed. -

Citymac 2018

CityMac 2018 City, University of London, 5–7 July 2018 Sponsored by the Society for Music Analysis and Blackwell Wiley Organiser: Dr Shay Loya Programme and Abstracts SMA If you are using this booklet electronically, click on the session you want to get to for that session’s abstract. Like the SMA on Facebook: www.facebook.com/SocietyforMusicAnalysis Follow the SMA on Twitter: @SocMusAnalysis Conference Hashtag: #CityMAC Thursday, 5 July 2018 09.00 – 10.00 Registration (College reception with refreshments in Great Hall, Level 1) 10.00 – 10.30 Welcome (Performance Space); continued by 10.30 – 12.30 Panel: What is the Future of Music Analysis in Ethnomusicology? Discussant: Bryon Dueck Chloë Alaghband-Zadeh (Loughborough University), Joe Browning (University of Oxford), Sue Miller (Leeds Beckett University), Laudan Nooshin (City, University of London), Lara Pearson (Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetic) 12.30 – 14.00 Lunch (Great Hall, Level 1) 14.00 – 15.30 Session 1 Session 1a: Analysing Regional Transculturation (PS) Chair: Richard Widdess . Luis Gimenez Amoros (University of the Western Cape): Social mobility and mobilization of Shona music in Southern Rhodesia and Zimbabwe . Behrang Nikaeen (Independent): Ashiq Music in Iran and its relationship with Popular Music: A Preliminary Report . George Pioustin: Constructing the ‘Indigenous Music’: An Analysis of the Music of the Syrian Christians of Malabar Post Vernacularization Session 1b: Exploring Musical Theories (AG08) Chair: Kenneth Smith . Barry Mitchell (Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance): Do the ideas in André Pogoriloffsky's The Music of the Temporalists have any practical application? . John Muniz (University of Arizona): ‘The ear alone must judge’: Harmonic Meta-Theory in Weber’s Versuch . -

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models By: Irna Priore ―Further Considerations about the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker’s Five Interruption Models.‖ Indiana Theory Review, Volume 25, Spring-Fall 2004 (spring 2007). Made available courtesy of Indiana University School of Music: http://www.music.indiana.edu/ *** Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Article: Schenker’s works span about thirty years, from his early performance editions in the first decade of the twentieth century to Free Composition in 1935.1 Nevertheless, the focus of modern scholarship has most often been on the ideas contained in this last work. Although Free Composition is indeed a monumental accomplishment, Schenker's early ideas are insightful and merit further study. Not everything in these early essays was incorporated into Free Composition and some ideas that appear in their final form in Free Composition can be traced back to his previous writings. This is the case with the discussion of interruption, a term coined only in Free Composition. After the idea of the chord of nature and its unfolding, interruption is probably the most important concept in Free Composition. In this work Schenker studied the implications of melodic descent, referring to the momentary pause of this descent prior to the achievement of tonal closure as interruption. In his earlier works he focused more on the continuity of the line itself rather than its tonal closure, and used the notion of melodic line or melodic continuity to address long-range connections. -

Kostka, Stefan

TEN Classical Serialism INTRODUCTION When Schoenberg composed the first twelve-tone piece in the summer of 192 1, I the "Pre- lude" to what would eventually become his Suite, Op. 25 (1923), he carried to a conclusion the developments in chromaticism that had begun many decades earlier. The assault of chromaticism on the tonal system had led to the nonsystem of free atonality, and now Schoenberg had developed a "method [he insisted it was not a "system"] of composing with twelve tones that are related only with one another." Free atonality achieved some of its effect through the use of aggregates, as we have seen, and many atonal composers seemed to have been convinced that atonality could best be achieved through some sort of regular recycling of the twelve pitch class- es. But it was Schoenberg who came up with the idea of arranging the twelve pitch classes into a particular series, or row, th at would remain essentially constant through- out a composition. Various twelve-tone melodies that predate 1921 are often cited as precursors of Schoenberg's tone row, a famous example being the fugue theme from Richard Strauss's Thus Spake Zararhustra (1895). A less famous example, but one closer than Strauss's theme to Schoenberg'S method, is seen in Example IO-\. Notice that Ives holds off the last pitch class, C, for measures until its dramatic entrance in m. 68. Tn the music of Strauss and rves th e twelve-note theme is a curiosity, but in the mu sic of Schoenberg and his fo ll owers the twelve-note row is a basic shape that can be presented in four well-defined ways, thereby assuring a certain unity in the pitch domain of a composition. -

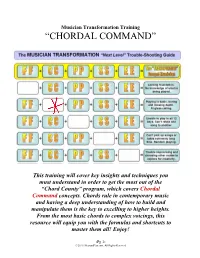

“Chordal Command”

Musician Transformation Training “CHORDAL COMMAND” This training will cover key insights and techniques you must understand in order to get the most out of the “Chord County” program, which covers Chordal Command concepts. Chords rule in contemporary music and having a deep understanding of how to build and manipulate them is the key to excelling to higher heights. From the most basic chords to complex voicings, this resource will equip you with the formulas and shortcuts to master them all! Enjoy! -Pg 1- © 2010. HearandPlay.com. All Rights Reserved Introduction In this guide, we’ll be starting with triads and what I call the “FANTASTIC FOUR.” Then we’ll move on to shortcuts that will help you master extended chords (the heart of contemporary playing). After that, we’ll discuss inversions (the key to multiplying your chordal vocaluary), primary vs secondary chords, and we’ll end on voicings and the difference between “voicings” and “inversions.” But first, let’s turn to some common problems musicians encounter when it comes to chordal mastery. Common Problems 1. Lack of chordal knowledge beyond triads: Musicians who fall into this category simply have never reached outside of the basic triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented) and are stuck playing the same chords they’ve always played. There is a mental block that almost prohibits them from learning and retaining new chords. Extra effort must be made to embrace new chords, no matter how difficult and unusual they are at first. Knowing the chord formulas and shortcuts that will turn any basic triad into an extended chord is the secret. -

MTO 18.4: Chenette, Hearing Counterpoint Within Chromaticism

Volume 18, Number 4, December 2012 Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory Hearing Counterpoint Within Chromaticism: Analyzing Harmonic Relationships in Lassus’s Prophetiae Sibyllarum Timothy K. Chenette NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.12.18.4/mto.12.18.4.chenette.php KEYWORDS: Orlandus Lassus (Orlando di Lasso), Prophetiae Sibyllarum, chromaticism, counterpoint, Zarlino, Vicentino, diatonicism, diatonic system, mode, analysis ABSTRACT: Existing analyses of the Prophetiae Sibyllarum generally compare the musical surface to an underlying key, mode, or diatonic system. In contrast, this article asserts that we must value surface relationships in and of themselves, and that certain rules of counterpoint can help us to understand these relationships. Analyses of the Prologue and Sibylla Persica demonstrate some of the insights available to a contrapuntal perspective, including the realization that surprising-sounding music does not always correlate with large numbers of written accidentals. An analysis of Sibylla Europaea suggests some of the ways diatonic and surface-relationship modes of hearing may interact, and highlights the features that may draw a listener’s attention to one of these modes of hearing or the other. Received April 2012 Introduction [1.1] Orlandus Lassus’s cycle Prophetiae Sibyllarum (1550s) is simultaneously familiar and unsettling to the modern listener. (1) The Prologue epitomizes its challenges; see Score and Recording 1. (2) It uses apparent triads, but their roots range so widely that it is difficult to hear them as symbols of an incipient tonality. The piece’s three cadences confirm, in textbook style, Mode 8, (3) but its accidentals complicate a modal designation based on the diatonic octave species. -

Understanding Ornamentation in Atonal Music Michael Buchler College of Music, Florida State University, U.S.A

Understanding Ornamentation in Atonal Music Michael Buchler College of Music, Florida State University, U.S.A. [email protected] ABSTRACT # j E X. X E In 1987, Joseph Straus convincingly argued that prolongational & E claims were unsupportable in post-tonal music. He also, intentionally or not, set the stage for a slippery slope argument whereby any small E # E E E morsel of prolongationally conceived structure (passing tones, ? E neighbor tones, suspensions, and the like) would seem just as Example 1. An escape tone that is not “non-harmonic.” problematic as longer-range harmonic or melodic enlargements. Prolongational structures are hierarchical, after all. This paper argues Example 2 excerpts an oft-contemplated piece: that large-scale prolongations are inherently different from Schoenberg’s op. 19, no. 6. In mm. 3-4, E6, the highest note small-scale ones in atonal (and possibly also tonal) music. It also of this short movement, neighbors Ds6. This neighboring suggests that we learn to trust our analytical instincts and perceptions motion is the first new gesture that we hear following with atonal music as much as we do with tonal music and that we not repetitions of the iconic first two chords. Two bars later, we require every interpretive impulse to be grounded by strongly can hear an appoggiatura as the unprepared Gs enters and methodological constraints. resolves down to Fs. The Ds-E-Ds neighbor tone was also shown in a reductive analysis in Lerdahl (2001, 354), but I. INTRODUCTION AND EXAMPLES Lerdahl apparently disagrees with my appoggiatura designation, instead equating both Gs and Fs as members of On the face of it, this paper makes a very simple and “departure” sonorities. -

Fourier Phase and Pitch-Class Sum

Fourier Phase and Pitch-Class Sum Dmitri Tymoczko1 and Jason Yust2(B) Author Proof 1 Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA [email protected] 2 Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA [email protected] AQ1 Abstract. Music theorists have proposed two very different geometric models of musical objects, one based on voice leading and the other based on the Fourier transform. On the surface these models are completely different, but they converge in special cases, including many geometries that are of particular analytical interest. Keywords: Voice leading Fourier transform Tonal harmony Musical scales Chord geometry· · · · 1Introduction Early twenty-first century music theory explored a two-pronged generalization of traditional set theory. One prong situated sets and set-classes in continuous, non-Euclidean spaces whose paths represented voice leadings, or ways of mov- ing notes from one chord to another [4,13,16]. This endowed set theory with a contrapuntal aspect it had previously lacked, embedding its discrete entities in arobustlygeometricalcontext.AnotherpronginvolvedtheFouriertransform as applied to pitch-class distributions: this provided alternative coordinates for describing chords and set classes, coordinates that made manifest their harmonic content [1,3,8,10,19–21]. Harmonies could now be described in terms of their resemblance to various equal divisions of the octave, paradigmatic objects such as the augmented triad or diminished seventh chord. These coordinates also had a geometrical aspect, similar to yet distinct from voice-leading geometry. In this paper, we describe a new convergence between these two approaches. Specifically, we show that there exists a class of simple circular voice-leading spaces corresponding, in the case of n-note nearly even chords, to the nth Fourier “phase spaces.” An isomorphism of points exists for all chords regardless of struc- ture; when chords divide the octave evenly, we can extend the isomorphism to paths, which can then be interpreted as voice leadings.