Tree Communities, Microhabitat Characteristics, and Small Mammals Associated with the Endangered Rock Vole, Microtus Chrotorrhinus, in Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mammal Species Native to the USA and Canada for Which the MIL Has an Image (296) 31 July 2021

Mammal species native to the USA and Canada for which the MIL has an image (296) 31 July 2021 ARTIODACTYLA (includes CETACEA) (38) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei - Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 7. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Bos bison - American Bison 2. Oreamnos americanus - Mountain Goat 3. Ovibos moschatus - Muskox 4. Ovis canadensis - Bighorn Sheep 5. Ovis dalli - Thinhorn Sheep CERVIDAE - deer 1. Alces alces - Moose 2. Cervus canadensis - Wapiti (Elk) 3. Odocoileus hemionus - Mule Deer 4. Odocoileus virginianus - White-tailed Deer 5. Rangifer tarandus -Caribou DELPHINIDAE - ocean dolphins 1. Delphinus delphis - Common Dolphin 2. Globicephala macrorhynchus - Short-finned Pilot Whale 3. Grampus griseus - Risso's Dolphin 4. Lagenorhynchus albirostris - White-beaked Dolphin 5. Lissodelphis borealis - Northern Right-whale Dolphin 6. Orcinus orca - Killer Whale 7. Peponocephala electra - Melon-headed Whale 8. Pseudorca crassidens - False Killer Whale 9. Sagmatias obliquidens - Pacific White-sided Dolphin 10. Stenella coeruleoalba - Striped Dolphin 11. Stenella frontalis – Atlantic Spotted Dolphin 12. Steno bredanensis - Rough-toothed Dolphin 13. Tursiops truncatus - Common Bottlenose Dolphin MONODONTIDAE - narwhals, belugas 1. Delphinapterus leucas - Beluga 2. Monodon monoceros - Narwhal PHOCOENIDAE - porpoises 1. Phocoena phocoena - Harbor Porpoise 2. Phocoenoides dalli - Dall’s Porpoise PHYSETERIDAE - sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus – Sperm Whale TAYASSUIDAE - peccaries Dicotyles tajacu - Collared Peccary CARNIVORA (48) CANIDAE - dogs 1. Canis latrans - Coyote 2. -

Rock Vole (Microtus Chrotorrhinus)

Rock Vole (Microtus chrotorrhinus) RANGE: Cape Breton Island and e. Quebec w. tone. Min- HOMERANGE: Unknown. nesota. The mountains of n. New England, s, in the Ap- palachians to North Carolina. FOOD HABITS:Bunchberry, wavy-leafed thread moss, blackberry seeds (Martin 1971). May browse on RELATIVEABUNDANCE IN NEW ENGLAND:Unknown, possi- blueberry bushes (twigs and leaves), mushrooms, and bly rare, but may be locally common in appropriate hab- Clinton's lily. A captive subadult ate insects (Timm et al. itat. 1977). Seems to be diurnal with greatest feeding activity taking place in morning (Martin 1971). Less active in HABITAT:Coniferous and mixed forests at higher eleva- afternoon in northern Minnesota (Timm et al. 1977). tions. Favors cool, damp, moss-covered rocks and talus slopes in vicinity of streams. Kirkland (1977a) captured COMMENTS:Occurs locally in small colonies throughout rock voles in clearcuts in West Virginia, habitat not pre- its range. Natural history information is lacking for this viously reported for this species. Timm and others (1977) species. Habitat preferences seem to vary geographi- found voles using edge between boulder field and ma- cally. ture forest in Minnesota. They have been taken at a new low elevation (1,509 feet, 460 m) in the Adirondacks KEY REFERENCES:Banfield 1974, Burt 1957, Kirkland (Kirkland and Knipe 1979). l97?a, Martin 1971, Timm et al. 1977. SPECIALHABITAT REQUIREMENTS: Cool, moist, rocky woodlands with herbaceous groundcover and flowing water. REPRODUCTION: Age at sexual maturity: Females and males are mature when body length exceeds 140 mm and 150 mm, respectively, and total body weight exceeds 30 g for both sexes (Martin 1971). -

Moles, Shrews, Mice, and More

Moles, RESEARCHERS FOCUS IN ON Shrews, NEW HAMPSHIRE’S MANY SMALL Mice MAMMALS and more 8 NovemberSeptember / / December October 2016 2016 by ELLEN SNYDER mall mammals – those weighing less than six ounces – are a surprisingly diverse group. In New England, they include mice, voles, bog lemmings, flying squir- Srels, chipmunks, moles and shrews. Researchers study small mammals because they are common, widespread, diverse, easily handled and reproduce often. My father, Dana Snyder, was one of those researchers. In the 1960s, when I was just four years old, he began a long-term study of the ecology of the eastern chipmunk in the Green Mountains of southern Vermont. Our summer camping trips to his study site infused me with a fondness for small mammals, especially chipmunks. Chipmunks are one of those small mammals that both entertain and annoy. Colorful in their brown and white stripes, they are lively and active during the day. When star- tled, they emit a high-pitched “chip” before darting off to a hideout; their low chuck, chuck, chuck is a common summer sound in our woods. They can stuff huge numbers of seeds into their cheek pouches. Despite their prevalence, chipmunks live solitary lives and are highly territorial. In winter, they take a long nap, waking occasionally to eat stored seeds or emerge above ground on a warm winter day. When I was in elementary school, my dad brought home an orphaned flying squirrel. We were enthralled with its large, dark eyes and soft fur. It would curl up in my shirt pocket, and I took it to school for show-and-tell. -

Morphological Disparity Among Rock Voles of the Genus <I>Alticola</I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Halle-Wittenberg Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 2012 Morphological Disparity among Rock Voles of the Genus Alticola from Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Russia (Rodentia, Cricetidae) V. N. Bolshakov Russian Academy of Sciences, [email protected] I. A. Vasilyeva Russian Aacdemy of Sciences A. G. Vasilyev Russian Academy of Sciences Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Bolshakov, V. N.; Vasilyeva, I. A.; and Vasilyev, A. G., "Morphological Disparity among Rock Voles of the Genus Alticola from Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Russia (Rodentia, Cricetidae)" (2012). Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298. 13. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Copyright 2012, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle Wittenberg, Halle (Saale). Used by permission. Erforsch. biol. Ress. Mongolei (Halle/Saale) 2012 (12): 105 –115 Morphological disparity among Rock voles of the genus Alticola from Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Russia (Rodentia, Cricetidae) V.N. Bolshakov, I.A. -

Peer and Partner Comments Received for SGCN: Mammals

Peer and Partner Comments Received for SGCN: Mammals Compiled October 2014 MDIFW’s responses (in blue) to peer and partner comments were provided by Wally Jakubas, Research and Assessment Section, and were reviewed by the respective species specialists and section supervisor. For comments related to the general process for designating species of greatest conservation need, please see the presentations ‘SGCN Process’ from the July 8, 2014 meeting and ‘Revised SGCN Process’ from the September 30, 2014 meeting on Maine’s Wildlife Action Plan revision website (http://www.maine.gov/ifw/wildlife/reports/MWAP2015.html). Please direct any questions to [email protected]. 1. Email from Mac Hunter (7/7/14) I might have listed some other bats based on Criterion 6 --like the three long distant migrants--given the dearth of information. See response to Comment 2 below. 2. Comments from July 8, 2014 break-out group Tree bats are conspicuously absent from the list. There are concerns over the impacts of wind power on these species. All of Maine’s tree bats have been labelled Special Concern (traditionally implying potential ET candidate species) since 1994. MDIFW agrees that all bat species should receive greater attention than they have in the past. Currently, MDIFW is planning to participate in the North American Bat Monitoring program, whose goal is to monitor bat population trends at local, state, regional, and continental levels. This program includes the monitoring of tree bats. The need for monitoring alone does not drive the SGCN ranking process. Given that monitoring will occur for our cave bats, which are proposed for SGCN ranking, we feel that concerns over the population trends of tree bats (i.e., hoary bat [Lasiurus cinereus], silver-haired bat [Lasionycteris noctivagans], and eastern red bat [Lasiurus borealis]), will be met by our overall bat monitoring efforts. -

Small Mammal Survey of the Nulhegan Basin Division of the Silvio 0

Small Mammal Survey of the Nulhegan Basin Division of the Silvio 0. Conte NFWR and the State of Vermont's West Mountain Wildlife Management Area, Essex County Vermont • Final Report March 15, 2001 C. William Kilpatrick Department of Biology University of Vermont Burlington, Vermont 05405-0086 A total of 19 species of small mammals were documented from the Nulhegan Basin Division of the Silvio 0. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge (NFWR) and the West Mountain Wildlife Management Area Seventeen of these species had previously been documented from Essex County, but specimens of the little brown bat (Jr{yotis lucifugu.s) and the northern long-eared bat (M septentrionalis) represent new records for this county. Although no threatened or endangered species were found in this survey, specimens of two rare species were captured including a water shrew (Sorex palustris) and yellow-nosed voles (Microtus chrotorrhinus). Population densities were relatively low as reflected in a mean trap success of 7 %, and the number of captures of two species, the short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) and the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), were noticeably low. Low population densities were observed in northern hardwood forests, a lowland spruce-fir forest, a black spruce/dwarf shrub bog, and most clear-cuts, whereas the high population densities were found along talus slopes, in a mixed hardwood forest with some • rock ledges, and in a black spruce swamp. The highest species diversity was found in a montane yellow birch-red spruce forest, a black spruce swamp, a beaver/sedge meadow, and a talus slope within a mixed forest. -

Moles, Shrews, Mice and More

Moles, RESEARCHERS FOCUS IN ON Shrews, NEW HAMPSHIRE’S MANY SMALL Mice MAMMALS and more 8 NovemberSeptember / / December October 2016 2016 by ELLEN SNYDER mall mammals – those weighing less than six ounces – are a surprisingly diverse group. In New England, they include mice, voles, bog lemmings, flying squir- Srels, chipmunks, moles and shrews. Researchers study small mammals because they are common, widespread, diverse, easily handled and reproduce often. My father, Dana Snyder, was one of those researchers. In the 1960s, when I was just four years old, he began a long-term study of the ecology of the eastern chipmunk in the Green Mountains of southern Vermont. Our summer camping trips to his study site infused me with a fondness for small mammals, especially chipmunks. Chipmunks are one of those small mammals that both entertain and annoy. Colorful in their brown and white stripes, they are lively and active during the day. When star- tled, they emit a high-pitched “chip” before darting off to a hideout; their low chuck, chuck, chuck is a common summer sound in our woods. They can stuff huge numbers of seeds into their cheek pouches. Despite their prevalence, chipmunks live solitary lives and are highly territorial. In winter, they take a long nap, waking occasionally to eat stored seeds or emerge above ground on a warm winter day. When I was in elementary school, my dad brought home an orphaned flying squirrel. We were enthralled with its large, dark eyes and soft fur. It would curl up in my shirt pocket, and I took it to school for show-and-tell. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Hickory Nut Gorge Green Salamander (Aneides caryaensis) Photo by Austin Patton 2014 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. The list is published periodically, generally every two years. -

List of Taxa for Which MIL Has Images

LIST OF 27 ORDERS, 163 FAMILIES, 887 GENERA, AND 2064 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 JULY 2021 AFROSORICIDA (9 genera, 12 species) CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles 1. Amblysomus hottentotus - Hottentot Golden Mole 2. Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole 3. Eremitalpa granti - Grant’s Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus - Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale cf. longicaudata - Lesser Long-tailed Shrew Tenrec 4. Microgale cowani - Cowan’s Shrew Tenrec 5. Microgale mergulus - Web-footed Tenrec 6. Nesogale cf. talazaci - Talazac’s Shrew Tenrec 7. Nesogale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 8. Setifer setosus - Greater Hedgehog Tenrec 9. Tenrec ecaudatus - Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (127 genera, 308 species) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale 2. Eubalaena australis - Southern Right Whale 3. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale 4. Eubalaena japonica - North Pacific Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei – Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale 7. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 8. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE (54 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Common Impala 3. Aepyceros petersi - Black-faced Impala 4. Alcelaphus caama - Red Hartebeest 5. Alcelaphus cokii - Kongoni (Coke’s Hartebeest) 6. Alcelaphus lelwel - Lelwel Hartebeest 7. Alcelaphus swaynei - Swayne’s Hartebeest 8. Ammelaphus australis - Southern Lesser Kudu 9. Ammelaphus imberbis - Northern Lesser Kudu 10. Ammodorcas clarkei - Dibatag 11. Ammotragus lervia - Aoudad (Barbary Sheep) 12. -

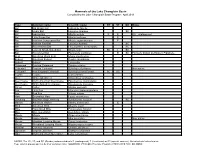

Mammals of the Lake Champlain Basin Compiled by the Lake Champlain Basin Program April 2013

Mammals of the Lake Champlain Basin Compiled by the Lake Champlain Basin Program April 2013 Type Common name Scientific name NY VT QC Notes Bat Big Brown Bat Eptesicus fuscus Bat Hoary Bat Lasiurus cinereus SC Bat Indiana Bat Myotis sodalis E E US - endangered Bat Little Brown Bat Myotis lucifugus E Bat Northern Long-eared Bat Myotis septentrionalis E Bat Eastern Red Bat Lasiurus borealis SC Bat Silver-haired Bat Lasionycteris noctivagans SC Bat Eastern Small-footed Bat Myotis leibii SC T SC Bat Tri-colored Bat Perimyotis subflavus E SC Formerly known as Eastern Pipistrelle Bear American Black Bear Ursus americanus Beaver American Beaver Castor canadensis Bobcat Bobcat Lynx rufus Chipmunk Eastern Chipmunk Tamias striatus Cottontail Eastern Cottontail Sylvilagus floridanus Non-native Cottontail New England Cottontail Sylvilagus transitionalis SC SC Coyote Coyote Canis latrans Deer White-tailed Deer Odocoileus virginianus Deermouse North American Deermouse Peromyscus maniculatus Deermouse White-footed Deermouse Peromyscus leucopus Fisher Fisher Martes pennanti Fox Gray Fox Urocyon cinereoargenteus Fox Red Fox Vulpes vulpes Hare Snowshoe Hare Lepus americanus Lemming Southern Bog Lemming Synaptomys cooperii SC Marten American Marten Martes americana E Mink American Mink Mustela vison Mole Hairy-tailed Mole Parascalops breweri Mole Star-nosed Mole Condylura cristata Moose Moose Alces americanus Mouse House Mouse Mus musculus Non-native Mouse Meadow Jumping Mouse Zapus hudsonius Mouse Woodland Jumping Mouse Napaeozapus insignis Muskrat Common Muskrat Ondata zibethicus Opossum Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana Otter North American River Otter Lutra canadensis NOTES: The NY, VT, and QC (Québec) columns indicate E (endangered), T (threatened) or SC (special concern). -

Small Mammals

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Maine Appalachian Trail Rare Mammal Inventory from 2006-2008 Natural Resource Report NPS/NETN/NRR—2010/177 ON THE COVER Yellow-nosed Vole (Microtus chrotorrhinus) Photograph by: Tim Divoll Maine Appalachian Trail Rare Mammal Inventory from 2006-2008 Natural Resource Report NPS/NETN/NRR—2010/177 David Yates, Sarah Folsom, and David Evers BioDiversity Research Institute 19 Flaggy Meadow Rd Gorham, Maine 04038 February 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This report received formal peer review by subject-matter experts who were not directly involved in the collection, analysis, or reporting of the data, and whose background and expertise put them on par technically and scientifically with the authors of the information. Views, statements, findings, conclusions, recommendations, and data in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect views and policies of the National Park Service, U.S. -

Banisteria, Number 14, 1999

Banisteria 14: 36-38 © 1999 by the Virginia Natural History Society Additional Records of the Rock Vole, Microtus chrotorrhinus (Miller) (Mammalia: Rodentia: Muridae), in Virginia. John L. Orrock Department of Biology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia 23284-2012 Elizabeth K. Harper Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota 55108 John F. Pagels Department of Biology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia 23284-2012 William J. McShea Conservation and Research Center, Smithsonian Institution, 1500 Remount Road, Front Royal, Virginia 22630 The southern Appalachian mountains support a rich small mammal study of 353 sampling sites within the small mammal fauna, with representatives that are George Washington and Jefferson National Forests. An typical of boreal climes often existing in sympatry with effort was made to sample all habitat types present in species associated with southern regions (Guilday, the study area according to their abundance in the 1971). The rock vole, Microtus chrotorrhinus, is a boreal landscape, e.g., if xeric oak habitats constituted 50% of rodent whose geographic distribution extends from the entire study region, then 50% of the sampling sites eastern Canada south along the Appalachians to North were in xeric oak habitat. At each site, small mammals Carolina and Tennessee (Kirkland & Jannett, 1982). were sampled using eight Sherman live traps (8 x 9 x 23 Microtus chrotorrhinus typically inhabits moist, rocky cm) and one Tomahawk live trap (21 x 21 x 62 cm). A habitats within this region, although clearcuts and pitfall array consisting of three 0.5 l pitfalls connected disturbed habitats may also be utilized. Southern to a central 0.5 l pitfall with a 0.3 m high drift fence of populations are considered disjunct (Kirkland & aluminum screening was also installed within each site Jannett, 1982), and may be adversely affected by (Type 1B of Handley & Kalko, 1993).