A Lesson in Death by BJ Roach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embracing Change: Towards a Research-Led Learning Community

Embracing Change: Towards a Research-Led Learning Community Keynote speaker Sugata Mitra speaks about the future of education (transcript) October 27, 2017 Firstly, I’m very happy to be here, in this remarkable city and at this remarkable school. And I appreciate the fact that you’re trying to do something about the future—not many do. Particularly in education we have this great inertia. It doesn’t change. So if you’re a school principal, and you figure I need to change something, you’re worried that if you shake the system, a lot of people might object—the parents firstly, the politicians and sometimes even the teachers. Somehow, when it comes to education there are two things that go wrong. One is that we quite irrationally believe that our children should be educated the way we were educated. It doesn’t make any sense actually, but if you search inside, you’ll find a little voice that says, “That’s safe because I’m not a lunatic—as yet—so if my child goes through the same system, then maybe he or she will be alright.” The system doesn’t—and by the system, I mean the political system or the rulers—they don’t want to upset people. And the easiest way to upset people is to mess around with their children. So they lay off. You might have noticed if you look at politics around the world, every politician that comes to power, before coming to power says, “I will make sweeping changes in education.” And immediately after coming to power, they get busy with wars and that sort of thing. -

Detective Special Agent = DET. =SA Assistant

Detective = DET. Special Agent =SA Assistant Prosecuting Attorney =APA Unknown Male One= UM1 Unknown Male Two- UM2 Unknown Female= UF Tommy Sotomayor= SOTOMAYOR Ul =Unintelligible DET. Today is Thursday, November 6, 2014 and the time is 12:10 p.m. This is Detective with the St. Louis County Police Department's Bureau of Crimes Against Persons, . I'm here in a conference room, in the Saint Louis County Prosecuting Attorney's Office, with a, Special Agent, Special Agent of the F.B.I., and also present in the room is ... Sir, would you say your name for the recorder please? DET. Okay, and it's is that correct? That's correct. DET. Okay ... and what is your date of birth, ? DET. ...and your home address? DET. And do you work at all? DET. Do not. DET. Okay ... and what is your cell phone? What is my what now? DET. Cell phone? Number? DET. Yes Sir. DET. Okay and, a, did you say an apartment number with that? DET okay. mm hmm. DET. So ... you came down here, a, to the Prosecuting Attorney's Office, because you received a Grand Jury Subpoena, is that correct? That is correct. DET Okay and you received that Grand Jury Subpoena a few days ago? Yes. DET. Okay ... and since then, you had a conversation with a, at least one of the Prosecutors here, explaining to you that they would like you to come down to the office today, is that correct? Yes. DET. Okay, uhh ... having said that, a, I think your attendance at the Grand Jury will be later on this afternoon, or, or in a little bit here. -

The Dutch Shoe Mystery

The Dutch Shoe Mystery Ellery Queen To DR. S. J. ESSENSON for his invaluable advice on certain medical matters FOREWORD The Dutch Shoe Mystery (a whimsicality of title which will explain itself in the course of reading) is the third adventure of the questing Queens to be presented to the public. And for the third time I find myself delegated to perform the task of introduction. It seems that my labored articulation as oracle of the previous Ellery Queen novels discouraged neither Ellery’s publisher nor that omnipotent gentleman himself. Ellery avers gravely that this is my reward for engineering the publication of his Actionized memoirs. I suspect from his tone that he meant “reward” to be synonymous with “punishment”! There is little I can say about the Queens, even as a privileged friend, that the reading public does not know or has not guessed from hints dropped here and there in Opus 1 and Opus 2.* Under their real names (one secret they demand be kept) Queen pere and Queen fits were integral, I might even say major, cogs in the wheel of New York City’s police machinery. Particularly during the second and third decades of the century. Their memory flourishes fresh and green among certain ex-offi- cials of the metropolis; it is tangibly preserved in case records at Centre Street and in the crime mementoes housed in their old 87th Street apart- ment, now a private museum maintained by a sentimental few who have excellent reason to be grateful. As for contemporary history, it may be dismissed with this: the entire Queen menage, comprising old Inspector Richard, Ellery, his wife, their infant son and gypsy Djuna, is still immersed in the peace of the Italian hills, to all practical purpose retired from the manhunting scene . -

Tomorrow You Will Be Thinking About the Future Dana Dal Bo

TOMORROW YOU WILL “Genius. The ethereal beauty shines through, yet there is a constant, the constant of our primal fear, the primal scream denied, she rises, as we BE THINKING all should rise, magnificent and closer to God.” -Anonymous on 2012-02-13 17:07:37 Yuvutu “Bravo! usually one must drop acid to see such a sight. ABOUT Thank you for the trip (and saving me the cash) acid is getting rreally expensive. Ps. Playing Pink Floyd in the background (in reverse) would have been THE FUTURE a nice touch. -Crazy Larry on 2012-02-14 03:47:22 Yuvutu “Your work is amazing. Far beyond what you would expect from a porn site.” -faceboynyc on 2016-12-07 04:33:22 “j aime beaucoup c’est tordu et sexy à la fois sans vouloir te vexer” DANA DAL BO -comalot on 2017-01-08 05:15:09 TOMORROW YOU WILL BE THINKING ABOUT THE FUTURE DANA DAL BO January 20, 2017 www.danadalbo.com underskirt_ IN EXHIBITION Mirror, Monitor, Screen 2015 self-Less 2014-ongoing Marginal Cons(T)ent 2012-ongoing Disoriented Whore Trapped in Closet 2012 Leggy Barely Legal Goddess 2013 No ©opyright Intended 2017-1992 Contact Sheet 2017-1992 ...Still in the Running towards Becoming... 2014 Carbon Copy 2016 Tomorrow I Will Be Thinking About the Future 2013 THE ENTRANCE PART ONE : THE MIRROR NARCISSISM INFINITY VERACITY IDENTITY SELF SELFLESS SELFIE PART TWO : THE MONITOR SCOPOPHILIA MESMERISM HYSTERIA CENSORSHIP AUTHORITY CONSENT PART THREE : THE SCREEN TELEVISIONARY PIRACY MARS MAGNATE INCURSORATED SURVEILLANCE THE ESCAPE THE ENTRANCE Once upon a time there was limited stimulation (distraction) and an abundance of hours. -

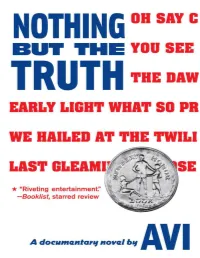

Nothing but the Truth Was First Published, I Had Trouble Getting a Reaction from the People It Was Written For: Kids

For Betty Miles Contents Title Page Dedication Preface 1 Tuesday, March 13 2 Thursday, March 15 3 Friday, March 16 4 Monday, March 19 5 Tuesday, March 20 6 Wednesday, March 21 7 Friday, March 23 8 Monday, March 26 9 Tuesday, March 27 10 Wednesday, March 28 11 Thursday, March 29 12 Friday, March 30 13 Saturday, March 31 14 Sunday, April 1 15 Monday, April 2 16 Tuesday, April 3 17 Wednesday, April 4 18 Friday, April 6 19 Monday, April 9 After Words™ About the Author Q&A with Avi “The Star-Spangled Banner” Two True, One False Three Sides of the Same Coin A Sneak Peek at Something Upstairs Also Available Copyright When Nothing But the Truth was first published, I had trouble getting a reaction from the people it was written for: kids. Teachers were taking the book and passing it around among themselves, insisting that their principals, assistant principals, and superintendents read it. Moreover, wherever I traveled, teachers would take me aside and say something like, “I know this book is about what happened in my school. Who was it who told you about what happened?” A principal once asked me if someone sent me his memos. A teacher from a school named Harrison High handed me a sheet of school stationery. The school’s logo was the lamp of learning that appears in the book. It got so that when I spoke to groups of teachers about the book, I took to asking, “Has anyone NOT heard of such an incident happening in your schools?” No one ever raised a hand. -

1 American High-Tech Transcription and Reporting

1 1 (INTERVIEW OF ALBERT L. HOFF, JR., #2016-0108, 08/09/16) 2 (The following may contain unintelligible or misunderstood 3 words due to the recording quality.) 4 5 CT = Special Agent Christopher Tissot 6 AH = Albert L. Hoff, Jr. 7 CT: My name is Christopher Tissot, Special Agent with 8 the Florida Department of Law Enforcement out of 9 Fort Myers. Today's date is currently August 9th, 10 2016, and the time is currently 11:12 p.m. This is 11 in reference to an incident which occurred at the 12 Punta Gorda Police Department, 1410 Tamiami Trail, 13 Punta Gorda, Florida. I will be taking a sworn, 14 taped statement from Albert Leroy Hoff, Jr., date of 15 birth August 12th, 1966, currently residing at 29235 16 Palm Shores Boulevard in Punta Gorda, Florida. Is 17 it okay if I call you Albert or would you -- 18 AH: Yes, sir. 19 CT: Okay. 20 AH: That's fine. 21 CT: All right. Before we begin I have to ask you, do 22 you know what perjury is? 23 AH: Yes, sir. 24 CT: In your own words, can you tell me what it is? 25 AH: Hmm. Pretty much not just telling the truth. 26 CT: Correct. Perjury is lying under oath. American High-Tech Transcription and Reporting, Inc. 0656 2 1 AH: Uh-huh. 2 CT: And that could occur one or two way -- in a couple 3 of ways, excuse me: either telling an outright lie 4 or misleading me by leaving out all or part of 5 information, okay, in order to mislead the 6 investigation. -

Stranger in a Strange Land” by Robert Heinlein

“Stranger In A Strange Land” by Robert Heinlein NOTICE: All men, gods; and planets in this story are imaginary, Any coincidence of names is regretted. Part One HIS MACULATE ORIGIN, 5 Fart Two HIS PREPOSTEROUS HERITAGE, 81 Fart Three HIS ECCENTRIC EDUCATION, 261 Part Four HIS SCANDALOUS CAREER, 363 Part Five HIS HAPPY DESTINY, 425 Preface IF YOU THINK that this book appears to be thicker and contain more words than you found in the first published edition of Stranger in a Strange Land, your observation is correct. This edition is the original one-the way Robert Heinlein first conceived it, and put it down on paper. The earlier edition contained a few words over 160,000, while this one runs around 220,000 words. Robert's manuscript copy usually contained about 250 to 300 words per page, depending on the amount of dialogue on the pages. So, taking an average of about 275 words, with the manuscript running 800 pages, we get a total of 220,000 words, perhaps a bit more. This book was so different from what was being sold to the general public, or to the science fiction reading public in 1961 when it was published, that the editors required some cutting and removal of a few scenes that might then have been offensive to public taste. The November 1948 issue of Astounding Science Fiction contained a letter to the editor suggesting titles for the issue of a year hence. Among the titles was to be a story by Robert A. Heinlein-"Gulf." In a long conversation between that editor, John W. -

Ecli:Nl:Rbdha:2020:2584

ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2020:2584 InstitutionRechtbank The Hague Date of pronunciation25-03-2020 Date of publication25-03-2020 Case number 12-1165 Areas of lawCivil law Special features Soil case Content indication Unlawful act of government. Executions in South Sulawesi by Dutch soldiers in 1946-1947. Evidence assessment. Award of shock damage to child who saw execution of father. Budget material damage (loss of income). LocationsRechtspraak.nl Ruling judgment COURT HEDGE Trade team Judgment of 25 March 2020 in the procedures of Case number / reel number: C/09/428182 / HA ZA 12-1165 2 [Claimant 1] , living at [residence 1] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 3. [plaintiff 2], living in [residence 1] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 4. [plaintiff 3], living at [residence 1] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 5. [Claimant 4], living at [residence 1] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 12. [Claimant 5], living at [residence 2] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 18. the foundation STICHTING KOMITE UTANG KEHORMATAN BELANDA, established in Heemskerk, Case number / reel number C/09/458254 / HA ZA 14-96: 2 [Claimant 6] , residing at [residence 3] , [residence 2] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 3. [Claimant 7], residing at [residence 4] , [residence 2] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 5. [plaintiff 8] living at [residence 5] , [residence 2] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 6. [plaintiff 9] living at [residence 6] , [residence 2] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 10. [plaintiff 10] residing at [residence 7] , [residence 2] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 11. [plaintiff 11] living at [residence 8] , [residence 2] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 12. [plaintiff 12] living at [residence 9] , [residence 2] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 13. [plaintiff 13] living at [residence 10] , [residence 10] , South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 18. -

MPD F Force-Sysialned (Category B) Remain Abviolation

Minneapolis City of Lahes Police Department Tim Oolan Chief of Police 350 South 5lh Street - Room 130 November 28, 2006 Minneapolis MN 55415-1389 Office 612 673-2853 TTY 612 673J157 Officer James Archer First Precinct iVIinneapolis Police Department RE; CRA Case Number 04-2155 Noticeof Suspension 'witfiout pay) Officer Archer, The finding for CRA Case #04-2155 is as follows: MPD R/R f5-103 Use of Discretion...SySTAlNED.(CategoryForce-SysiAlNED (CategoryB) B) As discipline for this incident you are suspended fo«hours without oav Thk no.. „ remain aBviolation and be held in your file for thref^ars ® Be advised that any additional violations of Department Rules and Rpnufatior, r.« i„ „,o„ .c.o„ „„ Sincerely, Timothy J. Dolan Chief of Police By: Sharon Lubin^i Assistant Chief Category: B I, James Archer, acknowledge receipt of this Notice Retain 4/3/2007 of Suspension. TJD:caa cc: Personnel lAU Case File imm •^Officer J. Archer Date CityInformation and Services www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us Affimiative Aclion Employer CITY OF MINNEAPOLIS CIVILIAN POLICE REVIEW AUTHORITY FINDINGS OF FACT AND DETERMINATION Complaint No.; 04-2155 Complainant: Subject Officer No. 1 Corporal James Archer Badge No., Duty Assignment: 00177, Precinct 1 Nightwatch Subject Officer No. 2 Badge No., Duty Assignment: Allegation 1: Inappropriate Conduct AJlegation 2: Excessive Force Complaint Investigator: Hearing Date: Pursuant to Minneapolis Code of Ordinance Title 9, Chapter 172 § 172.10, the M^eapoHs Civilian Police Review Authority (CRA) has the authority to adjudicate citizen complaints alleging misconduct against members of the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) as provided by that chapter. -

Gary Lee Goodman Ii

Entry 1: Indictment IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE TWENTY FIRST JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, IN AND FOR CAMDEN COUNTY, MAJOR CASE NO. 666 STATE OF MAJOR CHARGE(S): ‐vs‐ I. MURDER IN THE SECOND DEGREE GARY LEE GOODMAN II. ATTEMPTED MURDER IN Defendant. THE SECOND DEGREE III. CARRYING A CONCEALED FIREARM INDICTMENT IN THE NAME AND BY THE AUTHORITY OF THE STATE OF MAJOR: COUNT I: The Grand Jurors of the County of Camden, State of Major, charge that GARY LEE GOODMAN, on or about the 1st day of May, 20XX‐1, in the County and State aforesaid, did then and there committed the felony of murder in the second degree in that the said Gary Lee Goodman unlawfully and by an act imminently dangerous to another and evincing a depraved mind regardless of human life, but without a premeditated design to effect the death of any particular individual or person, did kill and murder MOE HELTON by shooting him with a firearm, to wit: a handgun, thereby inflicting in and upon MOE HELTON mortal wounds and injuries, of and from which said mortal wounds and injuries the said MOE HELTON did then and there die, contrary to Revised General Statute of Major and against the peace and dignity of the State of Major. COUNT II: The Grand Jurors of the County of Camden, State of Major, further charge that GARY LEE GOODMAN, on or about the 1st day of May, 20XX‐1, in the County and State aforesaid, did then and there unlawfully attempt to commit the felony of murder in the second degree in that said GARY LEE GOODMAN unlawfully and by an act imminently dangerous to another and evincing a depraved mind regardless of human life, but without a premeditated design to effect the death of any particular person, did shoot JOHN ELDER with a firearm, to wit: a handgun, thereby attempting to inflict in and upon JOHN ELDER mortal wounds and injuries, contrary to Revised General Statute of Major and against the peace and dignity of the State of Major. -

Robert Fink Professor IV Department of Musicology Chair, Music Industry Program FAC UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music Los Angeles, CA 90095-1623 03-03-2019

Music Industry 29 Robert Fink Professor IV Department of Musicology Chair, Music Industry Program FAC UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music Los Angeles, CA 90095-1623 03-03-2019 Michael Hackett, Chair General Education Governance Committee Attn: Chelsea Hackett, Program Representative A265 Murphy Hall Mail Code: 157101 Members of the GE Governance Committee: I am writing you in my role as Chair of the Faculty Advisory Committee for the Music Industry Minor in the Alpert School of Music to request GE credit be associated with two newly revised Music Industry classes: Music Industry 29 (formerly 109). The Music Documentary in History and Practice. Music Industry 55 (formerly 105). Songwriters on Songwriting. Both of these classes were approved in the FAC and approved as part of a general revision of the Music Industry Minor program requirements by the School of Music’s FEC. I am now submitting to you syllabi and GE Information sheets for both classes, as well as PDFs of the relevant CIMS forms, which have been routed to our School’s FEC Coordinator, Nam Ung. Please let me know if there is anything else I can do to help the process along. We hope to offer these courses with GE credit during Summer Sessions. Sincerely, Robert Fink Page 1 of 30 Music Industry 29 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Course Title Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities ñ Literary and Cultural Analysis ñ Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis ñ Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture ñ Historical Analysis ñ Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry (IMPORTANT: If you are only proposing this course for FSI, please complete the updated FSI information sheet. -

A Dissertation Entitled Explaining the Role of Emotional Valence In

A Dissertation entitled Explaining the Role of Emotional Valence in Children’s Memory Suggestibility by Travis Conradt Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Psychology ___________________________________________________ Kamala London, Ph.D., Committee Chair ___________________________________________________ Andrew Geers, Ph.D., Committee Member ___________________________________________________ John D. Jasper, Ph.D., Committee Member ___________________________________________________ Jason Rose, Ph.D., Committee Member ___________________________________________________ Charlene M. Czerniak, Ph.D., Committee Member ___________________________________________________ Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies University of Toledo August 2013 Copyright 2013, Travis W. Conradt This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Explaining the Role of Emotional Valence in Children’s Memory Suggestibility by Travis Conradt Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Psychology The University of Toledo August 2013 The present study addressed developmental differences in the effect of emotional valence on children’s suggestibility to an investigative interviewer using a controlled laboratory experiment. Children ages 6- to 11-years-old (N = 157) participated in watching a cartoon with either a positive or negative emotional outcome. Afterward, children were given an interview that included true and false leading questions. One-week later, children experienced a follow-up interview that assessed memory recall, true and false recognition, and source monitoring. Findings showed that children who witnessed the negative cartoon were more suggestible, as evidenced by heightened misinformation effects in the follow-up interview.