M I C G a N Jewis11 History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2020 Have Made Very Little Difference to Their Celebrations

KOL AMI Jewish Center & Federation New ideas of the Twin Tiers Congregation Kol Ami A different kind of Sukkot Jewish Community School When every Jewish household built a sukkah at home, a pandemic would October 2020 have made very little difference to their celebrations. Maybe fewer guests would have been invited for meals in the sukkah, and it might have been harder to obtain specialty fruits and vegetables, but the family had the suk- In this issue: kah and could eat meals in it, perhaps even sleep in it. Service Schedule 2 That is still widespread in Israel and in traditional communities here, but more of us rely on Sukkot events in the synagogue for our “sukkah time.” Torah/Haftarah & Candle Lighting 2 This year there won’t be a Sukkot dinner at Congregation Kol Ami and we Birthdays 4 won’t be together for kiddush in the sukkah on Shabbat (which is the first day of Sukkot this year). Mazal Tov 4 Nevertheless, Sukkot is Sukkot is Sukkot. It may be possible for you to CKA Donations 5 build a sukkah at home—an Internet search will find directions for building one quickly out of PVC pipe or other readily JCF Film Series 6 available materials. Sisterhood Opening Meeting 8 Even without a sukkah, we can celebrate the themes of Sukkot. In Biblical Israel it was a har- Jazzy Junque 8 vest festival, so maybe you can go to farm JCF Donations 8 stands and markets for seasonal produce. Baked squash is perfect for the cooler weather, Yahrzeits 9 cauliflower is at its peak—try roasting it—and In Memoriam 10 it’s definitely time for apple pie. -

Our Impact 3 Table of Contents

OUR IMPACT 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Taking Care of Needs (Vulnerable Populations & Urgent Needs) ................1 Local Agencies Hebrew Free Loan .....................................2 Jewish Family Service ....................................3 Jewish Senior Life .....................................4 JVS .............................................5 Overseas American Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) .......................6 Federation Community Needs Programs Community-Wide Security .................................7 Real Estate / Community Infrastructure ..........................8 Building A Vibrant Future (Jewish Identity and Community) . 9 Local Agencies BBYO ...........................................10 Jewish Community Center .................................11 Jewish Community Relations Council ...........................12 Tamarack Camps ......................................13 Hillel On Campus Michigan State University Hillel and the Hillel Campus Alliance of Michigan . 14 Hillel of Metro Detroit ...................................15 University of Michigan Hillel ...............................16 Jewish Day Schools Akiva Hebrew Day School .................................17 Jean and Samuel Frankel Jewish Academy .........................17 Hillel Day School .....................................17 Yeshiva Beth Yehudah ...................................17 Yeshiva Gedolah ......................................17 Yeshivas Darchei Torah ..................................17 Overseas Jewish Agency for Israel (JAFI) ...............................18 -

The Hebrew-Jewish Disconnection

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Master’s Theses and Projects College of Graduate Studies 5-2016 The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection Jacey Peers Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses Part of the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Peers, Jacey. (2016). The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection. In BSU Master’s Theses and Projects. Item 32. Available at http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses/32 Copyright © 2016 Jacey Peers This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. THE HEBREW-JEWISH DISCONNECTION Submitted by Jacey Peers Department of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Bridgewater State University Spring 2016 Content and Style Approved By: ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Joyce Rain Anderson, Chair of Thesis Committee Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Anne Doyle, Committee Member Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Julia (Yulia) Stakhnevich, Committee Member Date 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my mom for her support throughout all of my academic endeavors; even when she was only half listening, she was always there for me. I truly could not have done any of this without you. To my dad, who converted to Judaism at 56, thank you for showing me that being Jewish is more than having a certain blood that runs through your veins, and that there is hope for me to feel like I belong in the community I was born into, but have always felt next to. -

TUD 1910 Community

LOCATION KEY Culture, Recreation & Museums Maven Market Baltimore Public Library (Pikesville Branch) Pikesville Senior Center The Suburban Club Walgreens Reisterstown Road Library Giant . Goldberg's New York Bagels t Rd Shopping & Dining ur Mama Leah's Pizza WELLWOOD o Pikesville Branch of the Baltimore Public Library Maven Market C Pikesville Town Center d Walgreens l Pikesville Senior Center O Smith Ave. Giant The Suburban Club Pikesville Town Center Dunkin' Donuts Dunkin' Donuts (Two locations) Suburban Orthodox Toras Chaim Pikes Cinema Darchei Tzedek Sion’s Bakery Baltimore Hebrew Congregation The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf . Rite Aid ve A Giant PIKESVILLLE e FALLSTAFF Bais HaKnesses Ohr ad Hachaim (Rabbi Weiss) Pariser’s Bakery Sl Kol Torah (Rabbi Berger) Temple Oheb Shalom Kosher Markets & Dining Ohr Simcha Yeshiva Lev Shlomo Chevrei Tzedek Congregation Goldberg's New York Bagels Doogie’s BBQ & Grill, Serengeti Mama Leah's Pizza Mikvah of Baltimore Yeshivos AteresP Sunfresh Produce Market Vaad HaKashrus of Baltimore (Star-K) . a n r Shlomo's Kosher Meat and Fish Market CongregationL Beit Yaakov k Dougie's BBQ & Grill Sion’s Bakery H . le Knish Shop Edward A Myerberg Center Beiti Edmond Safra e d Seven Mile Market M ig R Shlomo's Kosher Meat and Fish Market n h Cr l Ohr Hamizrach Congregation o Shomrei Mishmeres Hakodesh l The Coee Bean e t s i s Seven Mile Market & Tea Leaf v s e A C Western Run Park M S v Chabad of Park Heights o David Chu's China Bistro e u d . Rite Aid Khol Ahavas Yisroel n Tzemach Tzedek Wasserman & Lemberger Inc WILLIAMSBURG r David Chu's China Bistro tr fo Nachal Chaim y il Bais Lubavitch, B Jewish Temples & Synagogues M Cheder Chabad lv Wasserman & Lemberger Inc d. -

Congregation Bet Haverim Hebrew & Religious School Calendar 5781

Congregation Bet Haverim Hebrew & Religious School Calendar 5781 as of August 18, 2020; COVID19 modifications Su M T W Th F Sa September 2020 Su M T W Th F Sa October 2020 1 2 3 4 5 13 Community Rosh Hashanah Celebration 1 2 3 2 Family Sukkot Celebration 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 18-20 Erev, Rosh Hashanah 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2-9 Erev, Sukkot 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 27-28 Kol Nidre, Yom Kippur 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 4 Religious School opening day 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 30 Hebrew School opening day 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 9 Simchat Torah & Consecration 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 30 29 30 31 17 Neshama Adler Eldridge Bat Mitzvah 18 Back to School Gathering 10:00 Su M T W Th F Sa November 2020 Su M T W Th F Sa December 2020 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 6 F3 (Family First Friday) Shabbat (Second, Third) 1 2 3 4 5 4 F3 Shabbat (Fifth) 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 11 School Closed, Veteran's Day 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 10-18 Erev, Chanukah 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 15 Bnai Mitzvah Parent Mtg (G5) 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 Chanukah Shabbat & Potluck 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 22, 25, 29 School Closed, Thanksgiving Break 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 13 RS Chanukah Celebration 11:30 29 30 27 28 29 30 31 13-20 Interfaith Rotating Winter Shelter 20, 23, 27, 30 School Closed, Winter Break Su M T W Th F Sa January 2021 Su M T W Th F Sa February 2021 1 2 2 Django Nachmanoff Bar Mitzvah 1 2 3 4 5 6 5 F3 Shabbat (Fourth) 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 3 School Closed, Winter Break 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 School Closed, Presidents' Day 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 18 School Closed, MLK Day 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 25, 26 Erev, Purim 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 28, 29 Erev, -

Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America

בס״ד בס״ד Learning from our Leaders Pirchei Agudas Yisroel of America While traveling to collect money. R’ During the night: Yaakov would keep his precious chidushei ...He’s quite Torah together with his money bags... naive... He even paid me to carry those PIRCHEI heavy bags with money This looks like sticking out, up to his Agudas Yisroel of America Vol: 6 Issue: 16 - כ"ז שבט, תשע"ט - a good place to room... February 2, 2019 stay overnight. פרשה: משפטים הפטרה: הדבר אשר היה אל ירמיהו... )ירמיהו לד:ח-כב, לג:כה-כו( מברכים ר״ח אדר א׳ )מולד אור ליום שלישי בשעה: חלקים 15 + 23:57( ר״ח אדר א: יום שלישי ורביעי דף יומי: חולין ס״ז ותן טל ומטר לברכה משיב הרוח ומוריד הגשם ברכי נפשי )שבת מנחה( מצות עשה: 23 מצות לא תעשה: 30 TorahThoughts עֶ בֶ ד עִ בְ רִ י The question is, why is the piercing done after the וְאִ ם אָ מֹר יֹאמַ ר הָ עֶבֶד אָהַבְתִ י אֶ ת אֲדֹנִי … וְ רָ צַ ע אֲ דֹ נָ י ו אֶ ת אָ זְ נ וֹ בַ מַ רְ צֵ עַ … ...In the morning... The thieves opened the money bags Money is If the servant will say, ‘I love my master’ … and the master has finished his term of service? Why are we piercing his ear to remind ?him about why he was originally sold .(שְ מוֹת כ״א:ה׳-ו׳) replaceable, but Oh no! Just look shall pierce his ear lobe said that ד׳ to explain why מְ כִ י ְל תָ א quotes a well-known רַ שִ ״ י My bags were my writings are at these holy writings. -

Partner with Us in Building Our Community Center !!!

ה“ב :The Board Rabbi Chaim Greenberg, Board member Mr.Menashe Hochstead, Board member 777 Mrs.Alizah F.Hochstead, Board member 777 Partner with us in building our community center !!! To donate your US tax deductible contribution: Please make your check payable to PEF Israel Endowment Funds Inc. Please be sure to include "HaKehilot HaChadoshot 580625614" in the memo line And can be sent to: PEF Israel Endowment Funds Inc. 630 Third Avenue Suite 1501 New York, NY 10017 Or to: HaKehilot HaChadashot P.O.B. 50125 . Beitar Illit , Israel, 9056702 For NIS contributions in Israel: HaKehilot HaChadashot P.O.B 50125 Beitar Illit 9056702 For wire donations Mercantile Bank: #17, Branch: #734 Beitar Illit, account: #47779, HaKehilot HaChadashot We appreciate your generous support Sincerely yours Rabbi Chaim Greenberg Chabad Community Center, Beitar Illit,Israel P.O.B. 50125 . Beitar Illit , Israel, 9056702 Phone: 972-52-770-3760, Fax : 972-2 -652-7340, Email: [email protected] A map of Chabad Beitar Illit, Israel Institutions in Beitar A young and vibrant town, founded 20 years ago, and currently home to sense of responsibility to do all that it can to strengthen children's Kollelim 45,000 people—more than half of whom are children. attachment to the Rebbe. Chassidus Kollel, Hadas neighborhood. The Chabad community is one of the largest in Israel, numbering more 770 will house all educational institutions as well as the Rebbe's room Torat Menahem Chassidus Kollel, HaGeffen neighborhood. than 450 families with more than 2000 children, keinyirbu. where bar mitzvah boys will put on tefillin for the first time. -

ZIONIST YOUTH Book

THE ZIONIST YOUTH MOVEMENT IN A CHANGING WORLD BY PAUL LIPTZ Paul Liptz, originally from Zimbabwe, made aliya on June 4, 1967. He was on the staff of the Jerusalem-based Institute for Youth Leaders from Abroad (The Machon) for ten years and now lectures in the Department of Middle East and African History, Tel Aviv University and at the Hebrew Union College, Jerusalem. He has travelled extensively in the world, conducting seminars and lecturing and has had a close relationship with the British Jewish Community for over thirty years. 1 FOREWORD The UJIA Makor Centre for Informal Jewish Education is a world-leading facility in CONTENTS its field. It is committed to promoting informal Jewish education and this publication marks an important contribution to the discussion of the Zionist youth movements. 2 Foreword Paul Liptz is an internationally renowned Jewish educator who specialises in infor- 4 Introduction mal Jewish education - indeed for many of his students and professional col- 5 Zionism: A Contemporary Look At Past leagues alike he has been an inspirational mentor. He has produced this timely article on the Zionist youth movements, reviewing their history and addressing 9 Jewish Youth Before 1948 the educational, ideological and social challenges ahead. Though the focus is 12 Jewish Life in the State Period upon the British context, the article has resonance for movements everywhere. 13 The Educator’s Challenge The youth movements continue to be a central feature of the Jewish youth serv- 15 The Educator and the Present Era ice in Britain today. In earlier generations, they were an option pursued by the minority but in more recent years the movements have increasingly become the 17 The Zionist Youth Movement largest provider of active teenage involvement in Jewish youth provision. -

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California

ALABAMA ARKANSAS N. E. Miles Jewish Day School Hebrew Academy of Arkansas 4000 Montclair Road 11905 Fairview Road Birmingham, AL 35213 Little Rock, AR 72212 ARIZONA CALIFORNIA East Valley JCC Day School Abraham Joshua Heschel 908 N Alma School Road Day School Chandler, AZ 85224 17701 Devonshire Street Northridge, CA 91325 Pardes Jewish Day School 3916 East Paradise Lane Adat Ari El Day School Phoenix, AZ 85032 12020 Burbank Blvd. Valley Village, CA 91607 Phoenix Hebrew Academy 515 East Bethany Home Road Bais Chaya Mushka Phoenix, AZ 85012 9051 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 Shalom Montessori at McCormick Ranch Bais Menachem Yeshiva 7300 N. Via Paseo del Sur Day School Scottsdale, AZ 85258 834 28th Avenue San Francisco, CA 94121 Shearim Torah High School for Girls Bais Yaakov School for Girls 6516 N. Seventh Street, #105 7353 Beverly Blvd. Phoenix, AZ 85014 Los Angeles, CA 90035 Torah Day School of Phoenix Beth Hillel Day School 1118 Glendale Avenue 12326 Riverside Drive Phoenix, AZ 85021 Valley Village, CA 91607 Tucson Hebrew Academy Bnos Devorah High School 3888 East River Road 461 North La Brea Avenue Tucson, AZ 85718 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Yeshiva High School of Arizona Bnos Esther 727 East Glendale Avenue 116 N. LaBrea Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85020 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Participating Schools in the 2013-2014 U.S. Census of Jewish Day Schools Brandeis Hillel Day School Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy 655 Brotherhood Way 9120 West Olympic Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94132 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Brawerman Elementary Schools Hebrew Academy of Wilshire Blvd. Temple 14401 Willow Lane 11661 W. -

All Positions.Xlsx

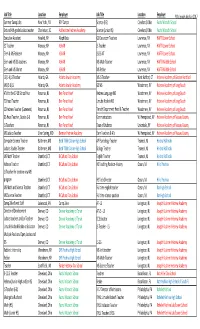

Job Title Location Employer Job Title Location Employer YU's Jewish Job Fair 2017 Summer Camp Jobs New York , NY 92Y Camps Science (HS) Cleveland, Ohio Fuchs Mizrachi School 3rd and 4th grade Judaics teacher Charleston, SC Addlestone Hebrew Academy Science (Junior HS) Cleveland, Ohio Fuchs Mizrachi School Executive Assistant Hewlett, NY Aleph Beta GS Classroom Teachers Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School EC Teacher Monsey, NY ASHAR JS Teacher Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School Elem & MS Rebbeim Monsey, NY ASHAR JS/GS AT Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School Elem and MS GS teachers Monsey, NY ASHAR MS Math Teacher Lawrence, NY HAFTR Middle School Elem and MS Morot Monsey, NY ASHAR MS Rebbe Lawrence, NY HAFTR Middle School LS (1‐4) JS Teacher Atlanta, GA Atlanta Jewish Academy MS JS Teacher‐ West Hatford, CT Hebrew Academy of Greater Hartford MS (5‐8) JS Atlanta, GA Atlanta Jewish Academy GS MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach ATs for the 17‐18 School Year Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Hebrew Language MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach EC Head Teacher Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Limudei Kodesh MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach EC Hebrew Teacher (Ganenent) Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Tanach Department Head & Teacher Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach GS Head Teacher, Grades 1‐8 Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Communications W. Hempstead, NY Hebrew Academy of Nassau County JS Teachers Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Dean of Students Uniondale, NY Hebrew Academy of Nassau County MS Judaics Teacher Silver Spring, MD Berman Hebrew Academy Elem Teachers & ATs W. -

Recent Trends in Supplementary Jewish Education

Recent Trends in Recent Trends in Recent Trends Jewish Education Supplementary Supplementary Jewish Education Jack Wertheimer JACK WERTHEIMER Adar 5767 March 2007 Recent Trends in Supplementary Jewish Education JACK WERTHEIMER Adar 5767 March 2007 © Copyright 2007, The AVI CHAI Foundation Table of Contents Letter from AVI CHAI’s Executive Director – North America 1 The Current Scene 3 A New Era? 3 Continuing Challenges to the Field 5 How Little We Know 7 Strategies for Change 10 Some Overall Strategic Issues 10 National Efforts 12 Local Initiatives 16 Evaluation 19 AVI CHAI’s Engagement with the Field 21 Acknowledgements 23 Letter from AVI CHAI’s Executive Director – North America Since its founding over two decades ago, The AVI CHAI Foundation has focused on Jewish education, primarily, in the past dozen years, to enhance day schools and summer camping. The Foundation also hopes to contribute to other arenas of Jewish education by supporting “thought leadership,” which may take the form of research, re-conceptualization, assessment and other intellectual initiatives. Toward that end, the Foundation commissioned this examination of recent trends in the field of supplementary Jewish education in order to help inform itself and a wider public concerned about such schooling. As a next step, AVI CHAI intends to support three research initiatives—described at the conclusion of the report—designed to stimulate new lines of inquiry in the field of supplementary Jewish education. As is clear from the report, the supplementary school field is in a process of evolution that is not yet well understood. Change provides both opportunities and challenges. -

The Roots and Development of Jewish Feminism in the United States, 1972-Present: a Path Toward Uncertain Equality

Aquila - The FGCU Student Research Journal The Roots and Development of Jewish Feminism in the United States, 1972-Present: A Path Toward Uncertain Equality Jessica Evers Division of Social & Behavioral Sciences, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty mentor: Scott Rohrer, Ph.D., Division of Social & Behavioral Sciences, College of Arts & Sciences ABSTRACT This research project involves discovering the pathway to equality for Jewish women, specifically in Reform Judaism. The goal is to show that the ordination of the first woman rabbi in the United States initiated Jewish feminism, and while this raised awareness, full-equality for Jewish women currently remains unachieved. This has been done by examining such events at the ordination process of Sally Priesand, reviewing the scholarship of Jewish women throughout the waves of Jewish feminism, and examining the perspectives of current Reform rabbis (one woman and one man). Upon the examination of these events and perspectives, it becomes clear that the full-equality of women is a continual struggle within all branches of American Judaism. This research highlights the importance of bringing to light an issue in the religion of Judaism that remains unnoticed, either purposefully or unintentionally by many, inside and outside of the religion. Key Words: Jewish Feminism, Reform Judaism, American Jewish History INTRODUCTION “I am a feminist. That is, I believe that being a woman or a in the 1990s and up to the present. The great accomplishments man is an intricate blend of biological predispositions and of Jewish women are provided here, however, as the evidence social constructions that varies greatly according to time and illustrates, the path towards total equality is still unachieved.