An Overlooked Truth: Our Dispatchers Are Exposed to Trauma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildfire and Poverty

Wildfire and Poverty An Overview of the Interactions Among Wildfires, Fire-Related Programs, and Poverty in the Western States The Center for Watershed and Community Health Mark O. Hatfield School of Government Portland State University P.O. Box 751 Portland, Oregon 97207 503-725-8101 or 541-744-7072 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.upa.pdx.edu/CWCH/ Prepared for the CWCH by ECONorthwest 99 West Tenth Ave., Suite 400 Eugene, Oregon 97401 December 2001 BACKGROUND AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As we enter the new millennium, the citizens of the West face an increasing number of important challenges. An economic downturn has placed the economy, communities, and workers at risk. The events of September 11 dramatically increased concerns about personal safety and the security of our transportation systems, water resources, energy systems, food supplies, and other issues that were previously taken for granted. These issues have emerged at a time when our environment continues to be a concern. In Oregon, for example, the Oregon State of the Environment Report, released in September 2000 by the Oregon Progress Board, identified a number of environmental areas where Oregonians can expect continued problems under current policies and programs including: poor water quality, especially in urban and agricultural areas, inadequate water supplies, loss of wetlands, degraded riparian areas, depleted fish stocks, invasion of exotic species, diminished biodiversity, and waste and toxic releases. Similar problems exist throughout the West. All of these issues contribute to forest health problems which exacerbate the risks of wildfires to humans and the environment. How can we maintain and enhance our economic security and protect workers and communities while also conserving the environment? The way Western states answer this question may turn out to be one of the most important challenges facing the region for the next number of years. -

Forest Fires in Ohio 1923 to 1935

BULLETIN 598 DECEMBER, 1938 Forest Fires in Ohio 1923 to 1935 Bernard E. Leete OHIO AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION Wooster, Ohio CONTENTS Introduction . 3 Area, Population, and Topographical Features of the Forest Fire District . 5 Organization of the Ohio Fire District . 8 Number of Fires . 12 Area Burned . 17 Damage .............................................................. 20 Cost of Suppression . 25 Statistics by Ten-Day Periods ........................................• 30 Causes of Fires . 88 Classification of Fires by Size . 53 (1) The first forest fire lookout tower in Ohio was built on Copperhead Hill, Shawnee State Forest, in 1924 FOREST FIRES IN OHIO 1923 TO 1935 BERNARD E. LEETE INTRODUCTION Fires in the hardwood forests of southern Ohio are similar in a general way as to behavior and effect to those of Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky, and other eastern hardwood states. Ohio fires practically .neve:t< "crown"; they creep or run along the ground; they are seldom spectacu lar; they have to date taken no toll in human life; they do not wipe out villages and towns in their path; and they may be controlled, if taken in time, with relative ease. Because of the enormous sprouting capacity of most of the native hardwood species and the luxuriant growth of sprouts, shrubs, and vines following a fire, the damage that has been done by an Ohio fire is frequently Qbscured from untrained eyes. The fires naturally vary greatly in intensity according to the weather conditions, the quantity and kinds of fuel present, the IJoint of origin with reference to the surrounding topography, and other such factors. The damage runs all the way from none at all to a total killing of the stand. -

LOOKOUT NETWORK (ISSN 2154-4417), Is Published Quarterly by the Forest Fire Lookout Association, Inc., Keith Argow, Publisher, 374 Maple Nielsen

VOL. 26 NO. 4 WINTER 2015-2016 LLOOKOOKOUTOUT NETWNETWORKORK THE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE FOREST FIRE LOOKOUT ASSOCIATION, INC. · 2016 Western Conference - June 10-12, John Day, Oregon · FFLA Loses Founding Member - Henry Isenberg · Northeast Conference - September 17-18, New York www.firelookout.org ON THE LOOKOUT From the National Chairman Keith A. Argow Vienna, Virginia Winter 2015-2016 FIRE TOWERS IN THE HEART OF DIXIE On Saturday, January 16 we convened the 26th annual member of the Alabama Forestry Commission who had meeting of the Forest Fire Lookout Association at the Talladega purchased and moved a fire tower to his woodlands; the project Ranger Station, on the Talladega National Forest in Talladega, leader of the Smith Mountain fire tower restoration; the publisher Alabama (guess that is somewhere near Talladega!). Our host, of a travel magazine that promoted the restoration; a retired District Ranger Gloria Nielsen, and Alabama National Forests district forester with the Alabama Forestry Commission; a U.S. Assistant Archaeologist Marcus Ridley presented a fine Forest Service District Ranger (our host), and a zone program including a review of the multi-year Horn Mountain archaeologist for the Forest Service. Add just two more Lookout restoration. A request by the radio communications members and we will have the makings of a potentially very people to construct a new effective chapter in Alabama. communications tower next to The rest of afternoon was spent with an inspection of the the lookout occasioned a continuing Horn Mountain Lookout restoration project, plus visits review on its impact on the 100-foot Horn Mountain Fire Tower, an historic landmark visible for many miles. -

USFA-TR-145 -- Tire Recycling Facility Fire

U.S. Fire Administration/Technical Report Series Tire Recycling Facility Fire Nebraska City, Nebraska USFA-TR-145/January-February 2002 U.S. Fire Administration Fire Investigations Program he U.S. Fire Administration develops reports on selected major fires throughout the country. The fires usually involve multiple deaths or a large loss of property. But the primary criterion T for deciding to do a report is whether it will result in significant “lessons learned.” In some cases these lessons bring to light new knowledge about fire--the effect of building construction or contents, human behavior in fire, etc. In other cases, the lessons are not new but are serious enough to highlight once again, with yet another fire tragedy report. In some cases, special reports are devel- oped to discuss events, drills, or new technologies which are of interest to the fire service. The reports are sent to fire magazines and are distributed at National and Regional fire meetings. The International Association of Fire Chiefs assists the USFA in disseminating the findings throughout the fire service. On a continuing basis the reports are available on request from the USFA; announce- ments of their availability are published widely in fire journals and newsletters. This body of work provides detailed information on the nature of the fire problem for policymakers who must decide on allocations of resources between fire and other pressing problems, and within the fire service to improve codes and code enforcement, training, public fire education, building technology, and other related areas. The Fire Administration, which has no regulatory authority, sends an experienced fire investigator into a community after a major incident only after having conferred with the local fire authorities to insure that the assistance and presence of the USFA would be supportive and would in no way interfere with any review of the incident they are themselves conducting. -

Rules for Building and Classing Facilities on Offshore Installations

Rules for Building and Classing Facilities on Offshore Installations RULES FOR BUILDING AND CLASSING FACILITIES ON OFFSHORE INSTALLATIONS JANUARY 2014 (Updated February 2014 – see next page) American Bureau of Shipping Incorporated by Act of Legislature of the State of New York 1862 Copyright 2013 American Bureau of Shipping ABS Plaza 16855 Northchase Drive Houston, TX 77060 USA Updates February 2014 consolidation includes: • January 2014 version plus Corrigenda/Editorials Foreword Foreword These Rules contain the technical requirements and criteria employed by ABS in the review and survey of hydrocarbon production facilities that are being considered for Classification and for maintenance of Classification. It is applicable to Hydrocarbon Production and Processing Systems and associated utility and safety systems located on fixed (bottom-founded) offshore structures of various types. It also applies to systems installed on floating installations such as ships shape based FPSOs, tension leg platforms, spars, semisubmersibles, etc. There are differences in the practices adopted by the designers of fixed and floating installations. Some of these differences are due to physical limitations inherent in the construction of facilities on new or converted floating installations. Recognizing these differences, the requirements for facilities on fixed and floating installations are specified in separate chapters. Chapter 3 covers requirements for facilities on floating installations and Chapter 4 covers requirements for facilities on fixed installations. Facilities designed, constructed, and installed in accordance with the requirements of these Rules on an ABS classed fixed or floating offshore structure, under ABS review and survey, will be classed and identified in the Record by an appropriate classification notation as defined herein. -

2016 Mid-Winter Muster February 19 – 21, 2016

2016 Mid-Winter Muster February 19 – 21, 2016 The Rapid Valley Fire Department, in- Registration will open from 5:30 p.m. to cooperation with Pennington County Fire, 7:00 p.m. on Friday evening and starting at 7 South Dakota Wildland Fire Division, and a.m. both Saturday and Sunday. Black Hills District of the South Dakota Firefighters Association is pleased to bring a Cost for the classes: $40 for FROG class variety of classes to this year’s event. We $30 for all other classes. are planning various one- and two day classes to meet the needs of all firefighters, Vendors will be on hand throughout the from new member to officer. weekend with the latest and greatest in firefighting apparel, tools, and equipment. The Mid-Winter Muster will be held February 19th through February 21st 2016, A block of rooms have been reserved for at the Best Western Ramkota (2111 N. $74.99/night. When reserving rooms, Lacrosse St.) in Rapid City. request the “Mid-Winter Muster” block rate. Course Listing (Please see next page) 2.5 Day Classes (Friday night, Saturday and Sunday) FROG: Fire Rescue Organizational Guidance for Volunteer Leaders Friday evening “heavy hors d'oeuvres” and lunch on Saturday will be provided (Class size limited to 40 students) 2 Day classes (Saturday and Sunday) NFA: Command and Control of Wildland Urban Interface Fire Operations (F0612) S131/S133: Firefighter Type 1/Look Up Look Down Look Around S230/S231: Blended Learning Single Resource Boss/Engine Boss 1 Day class (Saturday only) Rural Water Supply and Practical Hydraulics Wildland Fire Strategies and Tactics (Class size limited to 24 students) 1 Day class (Sunday only) Structure Fire Strategies and Tactics (Class size limited to 24 students) Course Descriptions •FROG: Fire Rescue Organizational Guidance for Volunteer Leaders This course is an intensive 2.5 day, hands-on workshop designed as graduate-level leadership training for leaders of volunteer and combination fire departments that picks up where VCOS's Beyond Hoses & Helmets course leaves off. -

Fire Safety Plan (FSP) Review Checklist1 (Component of a BC Fire Code (BCFC) Compliance Inspection)

Fire Safety Plan (FSP) Review Checklist1 (Component of a BC Fire Code (BCFC) compliance inspection) COMPANY INFORMATION Company name: Building Name: Address: ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Street # and name City/Province Postal Code Instructions: Place a ‘check mark’ for ‘Yes’, an ‘X’ for ‘No’, or N/A for ‘Not Applicable’ to each statement. Relevant information can be recorded in the Inspection Notes section on last page. At minimum, a fire safety plan (FSP) should include the following information: 1. Fire Safety Plan Review by Building Owner or Occupier (BCFC section 2.8.2.1.(2)): The fire safety plan is current: Reviewed within the past 12 calendar months There has not been any significant process or other operation changes since the last review that should be added to the plan. The individual(s)/company who prepared the fire safety plan or conducted the review is identified. Optional: Determine if the preparer(s) or reviewer(s) had the knowledge and experience to adequately prepare or review a fire safety plan. E.g., a strong background in fire prevention, fire code consulting, inspection procedures, planning or fire protection engineering. Note: Physical site visit can be used to determine if: I. Fire Safety Plan implemented as designed. II. All reasonably foreseeable fire and explosion hazards, in this building or property, have been identified. Site visit observations can be recorded on the Fire Prevention Inspection Report 2. Emergency procedures and information needed to plan for an emergency (BCFC section 2.8.2.1.(1)(a)): Contact personnel in the event of an emergency A list of names and telephone numbers of persons to be contacted during and after normal operating hours or in the event of an emergency is included. -

Fire Fighting Use of the Guide

FRANCESTOWN HERITAGE MUSEUM VISITORS GUIDE FIRE FIGHTING USE OF THE GUIDE The descriptions in this guide are numbered to correspond to the number on the card of the item you are viewing. If you would like additional information on any item please contact one of the curators or volunteers. There are five broad categories of items: 100-200 Series AGRICULTURE 600-800 Series COMMERCE 300-500 Series DOMESTIC LIFE 900 Series FIRE FIGHTING 1000 Series TRANSPORTATION Thank you for visiting the museum. PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE THE GUIDE FROM THE BUILDING. Personal copies are available with a donation suggested. Should you have any items that you would like to consider for donation, please contact one of the curators. We are a non-profit organization and any items donated are tax deductible. Cash donations are always welcome to help cover our operating, acquisition and maintenance expenses. FRANCESTOWN HERITAGE MUSEUM ITEM # 159 THE MUSEUM BUILDING The building in which you are standing was formerly a dairy barn located in Weare, NH. The building is dedicated to O. Alan Thulander who purchased this barn which was slated for demolition. Members of the Francestown Volunteer Fire Department disassembled the building and moved it to this current site where they re-erected the structure. New siding and roof boards were milled from trees located in the Town Forest. THE FIRE FIGHTING COLLECTION FRANCESTOWN HERITAGE MUSEUM ITEM # 901 THE HUNNEMAN HAND TUB This hand tub was originally purchased by the Elsworth, ME fire department whose members quickly learned it was not large enough for their growing city. -

Establishment Record for Mccaslin Mountain Research Natural Area Within the Nicolet National Forest, Forest County, Wisconsin

Decision Notfca Ffndfng of No Signtflcant Impact Qesignation Order By vlrtue of the authorq vested in me by the Secretary of Agricutture under reguiations 7 GFR 242, 36 CFR 251.a, and 36 CFR Part 21 9, t hereby establish the Meastin Mountan Research Naturaf Area shall be comprised of lands descnbecl in the seaon of the Establishment Record entrtled 'Location.' The Regtonal Forester has recommended the establishment of this Resear~ttNatural Area in the Record of Dectsion for the Nicolet National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan. That recommendation was the result of an matysis of the factors listed in 36 CFR 219.25 and Forest Service Manual 4063.41. Resufts of the Regional Forester's Anatysis are documented in the Niccltet Naional Forest Land and Resource Management PIan and Final Environmental Impact Staemem which are available to the public. The McCasiin Mountain Research Natural Area will be managed in compliance with ail relevant laws, rqulations, and Forest Sewice Mmu& dirmion rqilfding Rese3ct.t Ni;rtud Areas. It will be administered in accordance with the management directionlprescrivion identified in the Estab.lishment Record. 1 have reviewed the Nicofet Land and Resource Management P!an (LFb'!P) direction for this RNA and find that the managememt direction cited in the previous paragraph is consistent with the LRMP and that a PIan amendment is not required. The Forest Supervisor of the Nicoiet National Forest shall notrfy the public of this decision and will marl a copy of the Oecision NoticelDesignation Order and amended direction to all persons on the Nicolet National Forest Land and Resource Management PIan mailing list. -

Fire Management Notes Is Published by the Forest Service of the United States Francis R

United States Department of Agriculture Forest service Fire Management Volume 51, No.3 1990 Notes United States Department of Fire Agriculture Management Forest Service ~ totes An internationol quarterly periodical Volume 51, No.3 I ~ devoted to forest fire management 1990 Contents Short Features 3 First Wildland Firefighter Specialist Academy-a 11 Maggie's Poster Power Success! Donna Paananen Richard C. Wharton and Denny Bungarz 11 Michigan's Wildfire Prevention Poster Contest 5 Evaluating Wildfire Prevention Programs Donna M. Paananen, Larry Doolittle, and Linda 14 National Wildland Firefighters' Memorial Dedication: R. Donoghue A Centennial Event 9 Arsonists Do Not Set More Fires During Severe Fire 17 International Wildland Fire Conference Proceedings Weather in Southern California Romain Mees 17 Some BIG Thank You's 12 Fire Prevention for the 1990's-a Conference 19 Glossary of Wildland Fire Management Terms Malcolm Gramley and Sig. Palm 29 The Passamaquoddy Tribe Firefighters on the White 15 North Carolina Division of Forest Resources' Efforts Mountain National Forest in the Wake of Hurricane Hugo Tom Brady Rebecca Richards 35 New Wildfire Suppression Curriculum in Final 18 Reflections on 60 Years of Fire Control Review Phase Sam Ruegger Mike Munkres 20 Canadian Air Tanker and Crew in South Carolina Gloria Green 22 Forest Service Aircraft on Loan to State Forestry Agencies Fire Management Notes is published by the Forest Service of the United States Francis R. Russ Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. The Secretary of Agriculture has determined that the publication o! this periodical is necessary In the trensacnon of the public ousmess required by law of this Department. -

PARADE and MUSTER RULES

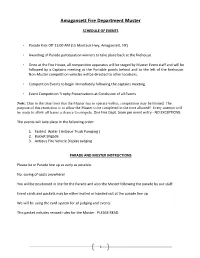

Amagansett Fire Department Muster SCHEDULE OF EVENTS • Parade Kick-Off 11:00 AM (15 Montauk Hwy, Amagansett, NY) • Awarding of Parade participation winners to take place back at the firehouse. • Once at the Fire House, all competition apparatus will be staged by Muster Event staff and will be followed by a Captains meeting at the Portable ponds behind and to the left of the firehouse. Non-Muster competition vehicles will be directed to other locations. • Competition Events to begin immediately following the captains meeting. • Event Competition Trophy Presentations at Conclusion of all Events Note: Due to the time limit that the Muster has to operate within, competition may be limited. The purpose of this restriction is to allow the Muster to be completed in the time allotted!! Every attempt will be made to allow all teams a chance to compete. One Fire Dept. team per event entry - NO EXCEPTIONS. The events will take place in the following order: 1. Fastest Water ( Antique Truck Pumping ) 2. Bucket Brigade 3. Antique Fire Vehicle Display Judging PARADE AND MUSTER INSTRUCTIONS Please be in Parade line up as early as possible. No. saving of spots anywhere! You will be positioned in line for the Parade and also the Muster following the parade by our staff. Event cards and packets may be either mailed or handed out at the parade line up. We will be using the card system for all judging and events. This packet includes revised rules for the Muster. PLEASE READ. 1 MUSTER GENERAL RULES 1. Judges decisions are final. Protests will be decided by the head event judges and chiefs. -

2017 Mid-Winter Muster February 17Th – 19Th, 2017

2017 Mid-Winter Muster February 17th – 19th, 2017 The Rapid Valley Fire Department, in- Registration will open from 5:00 p.m. to cooperation with Pennington County Fire, 7:00 p.m. on Friday evening and starting at 7 and South Dakota Wildland Fire Division, a.m. both Saturday and Sunday. are pleased to bring a variety of classes to this year’s event. We are planning various Cost for the classes: $30 per student one and two day classes to meet the needs of all firefighters, from new member to officer. Vendors will be on hand throughout the weekend with the latest and greatest in The Mid-Winter Muster will be held firefighting apparel, tools, and equipment. February 17th through February 19th 2017, at the Best Western Ramkota (2111 N. A block of rooms have been reserved for Lacrosse St.) in Rapid City. $99.99/night. When reserving rooms, request the “Mid-Winter Muster” block rate. There will be a social for networking and fellowship from 6:00-9:00 pm Friday night (17th), sponsored by Allegiant Emergency Services Inc. Course Listing (Please see next page) 2 Day classes (Saturday and Sunday) NFA: Leadership I for Fire and EMS S270: Basic Air Operations S230/S231: Blended Learning Single Resource Boss/Engine Boss 1 Day class (Saturday only) Wildland Fire Strategies and Tactics (Class size limited to 24 students) 1 Day class (Sunday only) Structure Fire Strategies and Tactics focused toward the volunteer fire service. Maps and Apps Course Descriptions (2-day classes) NFA: Leadership I for Fire and EMS This two-day course presents the basic leadership skills and tools needed to perform effectively in the fire service environment.