Political Blackface: Dave Wilson’S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NO. 2014-0211-1 City Council Chamber, City Hall, Tuesday, March 11, 2014 a Regular Meeting of the Houston City Council Was Held

NO. 2014-0211-1 City Council Chamber, City Hall, Tuesday, March 11, 2014 A Regular Meeting of the Houston City Council was held at 1:30 p.m. Tuesday, March 11, 2014, Mayor Annise Parker presiding, with Council Members Brenda Stardig, Ellen R. Cohen, Dwight Boykins, Dave Martin, Richard Nguyen, Oliver Pennington, Edward Gonzalez, Robert Gallegos, Mike Laster, Larry V. Green, Stephen C. Costello, David W. Robinson, Michael Kubosh, C. O. “Brad” Bradford and Jack Christie, D.C.; Mr. Harlan Heilman, Division Chief, Claims & Subrogation Division; and Ms. Marta Crinejo, Agenda Director, and Ms. Stella Ortega, Agenda Office, present. Council Member Jerry Davis out of the city on city business. At 1:42 p.m. Mayor Parker called the meeting to order and called on Council Member Green for a Council presentation. Council Members Stardig, Pennington, Gallegos, Laster, Robinson and Kubosh absent. Council Member Green stated that this week, March 11 through 15, 2014, Houston was proud to host the Men and Women 2014 Southwestern Athletic Conference Basketball Tournament, and presented a proclamation to the SWAC Men & Women Basketball Tournaments, and Mayor Parker stated therefore, she, Annise D. Parker, Mayor of the City of Houston, hereby proclaimed the week of March 11 through 15, 2014, as SWAC Basketball Week in Houston, Texas, that they were proud to make this announcement last year and now they were proud to host the tournament, that she wanted to thank everybody for being present and invited Dr. John Rudley, from their hometown team, who would be playing, to the podium. Council Members Stardig and Kubosh absent. -

Black Women's

Voices. Votes. Leadership. “At present, our country needs women's idealism and determination, perhaps more in politics than anywhere else.” Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm About Higher Heights Higher Heights is the only organization dedicated solely to harnessing Black women’s political power and leadership potential to overcome barriers to political participation and increase Black women’s participation in civic processes. Higher Heights Leadership Fund, a 501(c)(3), is investing in a long-term strategy to expand and support Black women’s leadership pipeline at all levels and strengthen their civic participation beyond just Election Day. Learn more at www.HigherHeightsLeadershipFund.org About The Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) The Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP), a unit of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is nationally recognized as the leading source of scholarly research and current data about American women’s political participation. Its mission is to promote greater knowledge and understanding about women's participation in politics and government and to enhance women's influence and leadership in public life. CAWP’s education and outreach programs translate research findings into action, addressing women’s under-rep- resentation in political leadership with effective, imaginative programs serving a variety of audiences. As the world has watched Americans considering female candidates for the nation's highest offices, CAWP’s over four decades of analyzing and interpreting women’s participation in American politics have provided a foundation and context for the discussion. Learn more at www.cawp.rutgers.edu This report was made possible by the generous support of Political Parity. -

Fredericksburg Reunion HPD News

PRSRT STD HOUSTON POLICE RETIRED OFFICERS ASSOCIATION US POSTAGE PAID P.O. BOX 2288, HOUSTON, TEXAS 77252-2288 HOUSTON, TX PERMIT NO. 9155 THE With Honor We Served . With Pride We Remember OFFICIALETI PUBLICATIONR OF THEED HOUSTON POLICE RETIREDADGE OFFICERS ASSOCIATION VOL.R XII, NO. 5 B October - November 2012 Fredericksburg Reunion The Hill Country Reunion will be held Saturday, Oct. 27, 2012 at Motels Available: Lady Bird park pavilion, 432 Lady Bird Drive, Fredericksburg, TX. This is the same place as last year. Peach Tree Inn & Suites 866/997-4347, 401 S. Washington St. The Super 8 Motel 800/466-8356, 830/997-4484, 501 E. Main St. The doors will be open at 9:00 AM and coffee will be ready. The (US 290) meal will be served at 12 Noon and will be “Catfish with all the The Sunday House 830/997-4484, 501 E. Main St. (US 290) trimmings”. We will hold another “silent auction” so if you have Fredericksburg Lodge 830/997-6568, 514 E. Main St. an item or two that you can donate please bring it with you, or The Best Western Motel 830/992-2929, 314 Highways St. drop it off at any HPROA meeting prior to the reunion. The La Quinta Inn 830/990-2899, 1465 East Main St. (US 290) Days Inn 800/320-1430, 808 S. Adams St. There are several events in Fredericksburg schedule for this Quality Inn 830/997-9811, 908 S. Adams St. weekend, and all Motels will fill up fast. Please make reservations Motel 6 800/466-8356, 705 Washington St. -

Shodalialat Jo Uoputtuojsmai

mob, re•ANII,~J. ...he..• A1,1161111.• •••••••111.1.11 winr.d 11.1110.11, alMOINEW Irb:40141111 .11011111111. I 411•111114110 sHodalialAT jo uoputtuojsmai N 0 1 S fl 0 H IlaahTfiN '6£ al/11E110A • C861 aNsir • INhialV aDill dO NOLIVIDOSSV C—, 0E11 SALLYPORT-JUNE 1983 2 Bad Timing (anthropology); and Geoffrey 3 The Pajama Game L. Winningham '65 (photog- 7 Under Milkwood raphy); subjects to be 8 To Be Or Not To Be/ Ministry of announced. Fear 11:45 A.M. Luncheon and Annual Convo- 9 My Dinner With Andre cation, including awarding of ANNOUNCEMENT 10 Come and Get It gold medals for distinguished 14 Rashoman service. Continuing Studies 15 The Third Man / Our Man in 2:00 P.M. Rice vs. Texas A&M, Rice Transfor- The Office of Continuing Studies and Special Havana Stadium. Houston: The 16 Special Treatment (premiere) 5:00-7:00 P.M. Dance to Big Band music Metropolis, Programs offers language courses designed mation of to develop conversational skills in Spanish, 17 The Man Who Laughs courtesy of John E. Dyson the by Jeffrey Karl Ochsner French, Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, Ger- 21 Dead of Night '43 in the Grand Hall of '73. As Houston comes man, Italian, Arabic, and Russian. Daytime 22 Dr. No / Alphaville RMC. 4 College alumni invited to indi- into its own as a major American courses in intensive English as a Second Lan- 23 The Last Detail the guage (ESL)are offered at nine levels of profi- 24 Whiskey Galore vidual colleges for a cookout. city, Rice alumni are in fore- Les Mistons /Jules and Jim Evening Reunion parties, including of growth. -

Badgegun Julyaugust 2015 Issue.Indd 1 8/3/15 7:56 AM the President’S Message Workers’ Comp Woes, Writing Your Will, and Mr

BADGE& Editorial GUN HPOU doesn’t shut up about Voice of the Houston Police Officers’ Union Published monthly at no subscription charge Brown’s Release but PUTS UP by the: $100,000 Reward for New Info Houston Police Officers’ Union YOU CAN STATE WITH A HIGH DEGREE of certainty that the Houston Police Officers Union, 1600 State Street, Houston, TX 77007 which represents all but just a few Houston police officers, puts up and doesn’t shut up. Ph: 832-200-3400 • Toll free: 1-800-846-1167 Fax: 832-200-3470 Earlier this summer the Union drew a crowd of local news media to announce that it was E-mail: [email protected] offering a $100,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the Website address: www.HPOU.org person who killed Officer Charles Clark 12 years ago during a check cashing robbery on the Southeast side. Legal Department: 832-200-3420 Legal Dept Fax: 832-200-3426 Houston Chronicle columnist Lisa Falkenberg won a Pulitzer Prize based on her columns that Insurance: 832-200-3410 resulted in getting the capital murder charges against Alfred Brown dismissed, thus freeing Badge & Gun is the official publication of the Brown from Death Row. Brown was originally convicted based on the best evidence presented Houston Police Officers’ Union. Badge & Gun is by Harris County prosecutors. Then the evidence was called into question within the last two published monthly under the supervision of its years when a phone record that corroborated Brown’s alibi was discovered in a detective’s Board of Directors. -

1963 – on the Steps of the Lincoln Memorial During the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Martin Luther King, Jr. Deliv

2011 - Osama bin Laden, 1962 - Confrontations among 1963 – On the steps of the Lincoln 1972 - The Anti-Ballistic Missile 1977 - Elvis Presley, the King 1980 - John Lennon, returning from 1984 – President Reagan defeats 1989 – Demolition begins on the 2010 - The Deepwater Horizon 1961 - President John F. 1967 - The world's rst human 1994 - Oklahoma City bombing 2000 - Incumbent Texas governor 2004 - Founded by Mark Zuckerberg 2009 - Pop icon Michael leader of al-Qaeda and the Soviet Union, Cuba and the Memorial during the March on 1969 – Apollo 11, of NASA's Treaty, a treaty between the of Rock and Roll dies in his 1978 - Camp David Accords, the Record Plant Studio with wife former Vice President Walter 1987 - In a speech at the Branden- Berlin Wall. Crowds cheer on both oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico Kennedy institutes the 1965 - The rst heart transplant is performed by 1970 - The Public Broadcasting 1973 - The Paris Peace kills 168 and wounds 800. The George Walker Bush wins the 2000 with his college roommates and fellow 2008 - U.S. oil prices hit a record Jackson dies, creating the mastermind of the Sep- United States in October of Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Apollo program, lands the United States and the Soviet 1974 - Hank Aaron of the home in Graceland at age 42. where Menachem Begin Yoko Ono, is shot by Mark David 1981 - Sandra Day O'Connor Mondale and is re-elected. burg Gate commemorating the sides as the bulldozers take away parts 1992 - Los Angeles riots result in 1998 - President Clinton is accused of 2002 - The United States Depart- explodes, sending millions of Peace Corps. -

History Map of the Houston Region George P

1836 1890 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 1519 -1685, 1690-1821 1685 -1690 1821 -1836 1836 -1845 1861 -1865 1845 -1861, 1870 Six Flags Over Texas 1974 2010 + 1904 1970s - 80s 2001 Sept 2005 Spain France Mexico Republic of Texas Confederate States of America The Woodlands founded by 1836 United States of America 1893 1895 Conroe founded 1969 Houston Downtown Tropical Storm Allison Hurricane Rita Houston Regional Growth History Map of the Houston Region George P. Mitchell 1999 population 2.1 Million; Galveston incorporated 1861 Pasadena founded Friendswood founded Kingwood tunnel system constructed 1993 1846 1930 1933 1968 Greater metropolitan area Planning and 1837 - 1840 Houston and 1894 1940s 1945 1948 1955 1959 founded Houston surpasses LA The SJRA 1976 Citywide referendum; population 6M Texas becomes Harris County 1870 Houston most populous city in Texas Humble founded Houston carries out Baytown Houston metro area Sugar Land in ozone readings Infrastructure Houston is the Capital of Pearland founded 1900 Katy 1962 (San Jacinto River Authority) Greenspoint 1983 Houston again rejects zoning the Republic 28th State vote to secede Texas readmitted 292,352 annexation campaign founded population 1 Million founded 1890s founded Houston voters reject proposed began construction of development begins Economic Development from the Union to the Union The Great Storm 1929 1935 to increase size Hurricane Sept 12, 2008 1837 Clear Lake 1955 zoning ordinance Lake Conroe pursuant to 1989 Aug 30, 1836 against Sam Population 9,332 City planning commission -

Lawsuit Seeks to Address an Appalling Violation of the Law: the Persistent and Intentional Failure to Test Thousands of Sexual Assault Evidence Kits (So Called

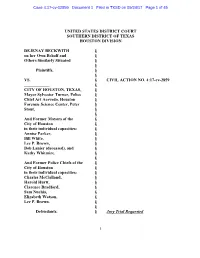

Case 4:17-cv-02859 Document 1 Filed in TXSD on 09/24/17 Page 1 of 45 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION DEJENAY BECKWITH § on her Own Behalf and § Others Similarly Situated § § Plaintiffs, § § VS. § CIVIL ACTION NO. 4:17-cv-2859 ____________ § CITY OF HOUSTON, TEXAS, § Mayor Sylvester Turner, Police § Chief Art Acevedo, Houston § Forensic Science Center, Peter § Stout, § § And Former Mayors of the § City of Houston § in their individual capacities: § Annise Parker, § Bill White, § Lee P. Brown, § Bob Lanier (deceased), and § Kathy Whitmire. § § And Former Police Chiefs of the § City of Houston § in their individual capacities: § Charles McClelland, § Harold Hurtt, § Clarence Bradford, § Sam Nuchia, § Elizabeth Watson, § Lee P. Brown. § § Defendants. § Jury Trial Requested 1 Case 4:17-cv-02859 Document 1 Filed in TXSD on 09/24/17 Page 2 of 45 ORIGINAL CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF THIS COURT: NOW COMES, Plaintiff, DEJENAY BECKWITH, who on her own behalf and on behalf of others similarly situated (hereinafter, collectively “Plaintiffs”), file this, Original Class Action Complaint against the CITY OF HOUSTON, TEXAS, Mayor Sylvester Turner, Police Chief Art Acevedo, the Houston Forensic Science Center, Peter Stout, CEO of the Houston Forensic Science Center as well as Former Mayors of the City of Houston: Annise Parker, Bill White, Lee P. Brown, Bob Lanier (deceased), and Kathy Whitmire in addition to Former Police Chiefs of the City of Houston: Charles McClelland, Harold Hurtt, Clarence -

Laying the Foundation for Complete Streets

Nov. 26, 2013 Progress Report: Laying the Foundation for Complete Streets - Houston Workshop, April 17, 2013 Workshop co-sponsored by: City of Houston –Mayor’s Office of Sustainability and Museum Park Super Neighborhood Made possible through: Environmental Protection Agency Building Blocks for Sustainable Communities Technical Assistance Grant through Smart Growth America, with support of the National Complete Streets Coalition. Submitted by: Lisa Lin, City of Houston Mayor’s Office of Sustainability; Kathleen O’Reilly, Museum Park Super Neighborhood VP Significant progress has been made in Houston since the April 17 Complete Streets Workshop (Workshop). The workshop included City and County leadership, and though focused on the Museum Park Super Neighborhood, the results have been widespread. Museum Park is an excellent case study to demonstrate the potential and need for more walkable, bicycle- and transit-friendly destinations in Houston. In light of recent progress, Houston may soon be a model for Complete Streets implementation throughout the United States. Activities held throughout the week of the workshop shed light on existing conditions through pedestrian and bike audits. These audits proved to be valuable tools to help guide Complete Street policy development. Key points from the April 25, 2013 SGA-Complete Streets Coalition Report are summarized below for completeness. At the time of the Workshop Mayor Annise Parker was working on an executive order regarding Complete Streets. This was a very deliberate process by the Mayor which resulted in a more sustentative and meaningful policy. Progress towards Complete Streets Current Quarter • October 10, 2013 – Draft Complete Streets Policy. The draft policy was announced by Mayor Parker at the site of Texas' first certified GreenRoads project, Bagby Street in Midtown. -

From “Lesbian Activist” to Beloved Mayor of Houston: a Conversation with Annise Parker

Journal of Family Strengths Volume 17 Issue 2 The Changing Landscape for LGBTIQ Article 11 Families: Challenges and Progress 12-31-2017 Voices from the Field: From “Lesbian Activist” to Beloved Mayor of Houston: A Conversation with Annise Parker Rebecca Pfeffer Ph.D. University of Houston - Downtown, [email protected] Robert Sanborn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs Recommended Citation Pfeffer, Rebecca Ph.D. and Robert Sanborn (2017) "Voices from the Field: From “Lesbian Activist” to Beloved Mayor of Houston: A Conversation with Annise Parker," Journal of Family Strengths: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 11. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol17/iss2/11 The Journal of Family Strengths is brought to you for free and open access by CHILDREN AT RISK at DigitalCommons@The Texas Medical Center. It has a "cc by-nc-nd" Creative Commons license" (Attribution Non- Commercial No Derivatives) For more information, please contact [email protected] Pfeffer and : Voices from the Field: From “Lesbian Activist” to Beloved Mayor o Drs. Pfeffer and Sanborn (JFS) conducted an interview with Annise Parker, former Mayor of the City of Houston, to discuss her career and some current issues of relevance to the LGBTQ community. The following interview has been edited for clarity. Annise Parker (AP) spent 18 years in public service for the city of Houston. From 1998-2003 she served on Houston City Council. She was elected to City Controller and served in this capacity from 2004-2010, before being elected as the Mayor of Houston from 2010-2016. -

From Hate Crimes to Activism: Race, Sexuality, and Gender in the Texas Anti-Violence Movement

FROM HATE CRIMES TO ACTIVISM: RACE, SEXUALITY, AND GENDER IN THE TEXAS ANTI-VIOLENCE MOVEMENT _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Christopher P. Haight May 2016 FROM HATE CRIMES TO ACTIVISM: RACE, SEXUALITY, AND GENDER IN THE TEXAS ANTI-VIOLENCE MOVEMENT _________________________ Christopher P. Haight APPROVED: _________________________ Nancy Beck Young, Ph.D. Committee Chair _________________________ Linda Reed, Ph.D. _________________________ Eric H. Walther, Ph.D. _________________________ Leandra Zarnow, Ph.D. _________________________ Maria C. Gonzalez, Ph.D. University of Houston _________________________ Steven G. Craig, Ph.D. Interim Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Economics ii FROM HATE CRIMES TO ACTIVISM: RACE, SEXUALITY, AND GENDER IN THE TEXAS ANTI-VIOLENCE MOVEMENT _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Christopher P. Haight May 2016 ABSTRACT This study combines the methodologies of political and grassroots social history to explain the unique set of conditions that led to the passage of the James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Act in Texas. In 2001, the socially conservative Texas Legislature passed and equally conservative Republican Governor Rick Perry signed the James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Act, which added race, color, religion, national origin, and “sexual preference” as protected categories under state hate crime law. While it appeared that this law was in direct response to the nationally and internationally high-profile hate killing of James Byrd, Jr. -

Thanks to the Entertainment Committee HPD Back Then

PRSRT STD HOUSTON POLICE RETIRED OFFICERS ASSOCIATION US POSTAGE PAID P.O. BOX 2288, HOUSTON, TEXAS 77252-2288 HOUSTON, TX PERMIT NO. 9155 THE With Honor We Served . With Pride We Remember OFFICIALETI PUBLICATIONR OF THEED HOUSTON POLICE RETIREDADGE OFFICERS ASSOCIATION VOL.R XIV, NO. 4 B August - September 2015 Thanks to the Entertainment Committee The HPROA Reunion was held this year at the Convention We want to also acknowledge and extend our special Center in Crockett, Texas on Saturday, June 27, 2015 with thanks to our Entertainment Chair Person, Phyllis Wunsche, 122 attendees present. The proceeds derived from the for her assistance in making this Reunion possible and a SILENT AUCTION was $2300.00 which was donated to the great success. Family Assistance Committee. We assure you that this donation will greatly aid in the Your Family Assistance Committee would like to thank all comfort and well being of our “sick and shut-ins.” that donated the items for the SILENT AUCTION. We also extend our thanks to those that actual won the bid for FAMILY ASSISTANCE COMMITTEE their generous contribution. The persons that worked the Forrest W. Turbeville, Chairman SILENT AUCTION were Steve and Vickie Rayne, E.J. and Nelson Foehner, Member Delores Smith, Phyllis Wunsche, Jose Weber, Sue Gaines and Doug Bostock, Member Barbara Cotten. We appreciate their assistance in making Ron Headley, Member this auction a great success. Ray Smith, Member HPD Back Then Recently while attending a retiree funeral, I could not I tugged at Freytag’s sleeve and advised him it was time to help but notice the same faces in attendance.