Initiative on Philanthropy in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIFI Holdings (Group) Co. Ltd. 旭 輝 控 股(集 團)有 限

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CIFI Holdings (Group) Co. Ltd. 旭輝控股(集團)有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 00884) ANNOUNCEMENT OF UNAUDITED INTERIM RESULTS FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2020 2020 INTERIM RESULTS HIGHLIGHTS • Recognized revenue increased by 11.3% year-on-year to RMB23.02 billion • Core net profit increased by 11.2% year-on-year to RMB3,194 million, with core net profit margin at 13.9%. Stable gross profit of approximately RMB5,901 million • Declared interim dividend of RMB9.8 cents (or equivalent to HK11 cents) per share, increased by 10% year-on-year • Contracted sales amounted to RMB80.7 billion with cash collection ratio from property sales achieved over 95% • As at 30 June 2020, net debt-to-equity ratio decreased by 2.4 percentage points to 63.2% comparing with that as at 31 December 2019. Abundant cash on hand of RMB59.4 billion • As at 30 June 2020, weighted average cost of indebtedness decreased by 0.4 percentage point to 5.6% comparing with that as at 31 December 2019 – 1 – INTERIM RESULTS The board of directors (the “Board”) of CIFI Holdings (Group) Co. Ltd. (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the unaudited consolidated results of the -

Beijing - Hotels

Beijing - Hotels Dong Fang Special Price: From USD 43* 11 Wan Ming Xuanwu District, Beijing Dong Jiao Min Xiang Special Price: From USD 56* 23 A Dongjiaominxiang, Beijing Redwall Special Price: From USD 66* 13 Shatan North Street, Beijing Guangxi Plaza Special Price: From USD 70* 26 Hua Wei Li, Chaoyang Qu, Beijing Hwa (Apartment) Special Price: From USD 73* 130 Xidan North Street, Xicheng District Beijing North Garden Special Price: From USD 83* 218-1 Wangfujing Street, Beijing Wangfujing Grand (Deluxe) Special Price: From USD 99* 57 Wangfujing Avenue, International Special Price: From USD 107* 9 Jian Guomennei Ave Dong Cheng, Beijing Prime Special Price: From USD 115* 2 Wangfujing Avenue, Beijing *Book online at www.octopustravel.com.sg/scb or call OctopusTravel at the local number stated in the website. Please quote “Standard Chartered Promotion.” Offer is valid from 1 Nov 2008 to 31 Jan 2009. Offer applies to standard rooms. Prices are approximate USD equivalent of local rates, inclusive of taxes. Offers are subject to price fluctuations, surcharges and blackout dates may apply. Other Terms and Conditions apply. Beijing – Hotels Jianguo Special Price: From USD 116* * Book online at www.octopustravel.com.sg/scb or call Octopus Travel at the local number stated in the website. Please quote “Standard Chartered Promotion.” Offer applies to standard rooms. Prices are approximate USD equivalent of local rates, inclusive of taxes. Offers are subject to price fluctuations, surcharges and blackout dates may apply. Other Terms and Conditions apply. 5 Jianguo Men Wai Da Jie, Beijing Novotel Peace Beijing • Special Price: From USD 69 (10% off Best unrestricted rate)* • Complimentary upgrade to next room category • Welcome Drink for 2 • Late checkout at 4pm, subject to availability • Complimentary accommodation and breakfast for 1 or 2 children *Best unrestricted rate refers to the best publicly available unrestricted rate at a hotel as at the time of booking. -

Evaluation of Households' Willingness to Accept the Ecological Restoration of Rivers Flowing in China

Evaluation of Households’ Willingness to Accept the Ecological Restoration of Rivers Flowing in China Zhang Yifei,a Sheng Li,b and Yuxi Luoc aResearch Center of Climate Change and Green Trade, International Business School, Shanghai University of International Business and Economics, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China bUniversity of Florida, Gulf Coast Research and Education Center, 14625 County Road 672, Wimauma, FL 33598; lisheng@ufl.edu (for correspondence) cSchool of Economics and Management, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, Guangxi, People’s Republic of China Published online 26 December 2018 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI 10.1002/ep.13094 During the past decade, many urban rivers in China have The contingent valuation method (CVM) is used to evaluate undergone ecological restoration overseen by government agen- the benefits of ecological restoration projects [1,2]. It assumes cies at the local and national level. Ecological restoration efforts that reliable information about the monetary values of specific such as this can improve the welfare of urban residents. This projects can be obtained from respondents if they are pro- study reports the willingness to accept (WTA) for Pingjiang and vided with sufficient information to make informed decisions. Guangtaiwei rivers degradation in Suzhou based on a contin- This prompts a consideration of the properties of different gent valuation study of 426 respondents. Our results indicate preference elicitation formats and how to best present informa- that 48% of respondents would not accept any money as com- tion related to the good of interest. Willingness to pay (WTP) pensation for river degradation. The mean WTA estimate for fi and willingness to accept (WTA) are two types of measure- those willing to accept a nite amount of compensation is ments in the CVM structure [3,4]. -

SGS-Safeguards 04910- Minimum Wages Increased in Jiangsu -EN-10

SAFEGUARDS SGS CONSUMER TESTING SERVICES CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 MINIMUM WAGES INCREASED IN JIANGSU Jiangsu becomes the first province to raise minimum wages in China in 2010, with an average increase of over 12% effective from 1 February 2010. Since 2008, many local governments have deferred the plan of adjusting minimum wages due to the financial crisis. As economic results are improving, the government of Jiangsu Province has decided to raise the minimum wages. On January 23, 2010, the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Jiangsu Province declared that the minimum wages in Jiangsu Province would be increased from February 1, 2010 according to Interim Provisions on Minimum Wages of Enterprises in Jiangsu Province and Minimum Wages Standard issued by the central government. Adjustment of minimum wages in Jiangsu Province The minimum wages do not include: Adjusted minimum wages: • Overtime payment; • Monthly minimum wages: • Allowances given for the Areas under the first category (please refer to the table on next page): middle shift, night shift, and 960 yuan/month; work in particular environments Areas under the second category: 790 yuan/month; such as high or low Areas under the third category: 670 yuan/month temperature, underground • Hourly minimum wages: operations, toxicity and other Areas under the first category: 7.8 yuan/hour; potentially harmful Areas under the second category: 6.4 yuan/hour; environments; Areas under the third category: 5.4 yuan/hour. • The welfare prescribed in the laws and regulations. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 P.2 Hourly minimum wages are calculated on the basis of the announced monthly minimum wages, taking into account: • The basic pension insurance premiums and the basic medical insurance premiums that shall be paid by the employers. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

New Oriental Education & Technology Group Inc

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(B) OR 12(G) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended May 31, 2011. OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☐ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report For the transition period from to Commission file number: 001-32993 NEW ORIENTAL EDUCATION & TECHNOLOGY GROUP INC. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) N/A (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) Cayman Islands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) No. 6 Hai Dian Zhong Street Haidian District, Beijing 100080 The People’s Republic of China (Address of principal executive offices) Louis T. Hsieh, President and Chief Financial Officer Tel: +(86 10) 6260-5566 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +(86 10) 6260-5511 No. 6 Hai Dian Zhong Street Haidian District, Beijing 100080 The People’s Republic of China (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Exchange on Which Registered American depositary shares, each representing one New York Stock Exchange common share* Common shares, par value US$0.01 per share New York Stock Exchange** * Effective August 18, 2011, the ratio of ADSs to our common shares was changed from one ADS representing four common shares to one ADS representing one common share. -

Shanghai Hanyu Medical Technology Co., Ltd.* 上海捍宇醫療科技股份

The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and the Securities and Futures Commission take no responsibility for the contents of this Application Proof, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Application Proof. Application Proof of Shanghai Hanyu Medical Technology Co., Ltd.* 上海捍宇醫療科技股份有限公司 (the “Company”) (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) WARNING The publication of this Application Proof is required by The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Exchange”)/the Securities and Futures Commission (the “Commission”) solely for the purpose of providing information to the public in Hong Kong. This Application Proof is in draft form. The information contained in it is incomplete and is subject to change which can be material. By viewing this document, you acknowledge, accept and agree with the Company, its sponsor, advisers or members of the underwriting syndicate that: (a) this document is only for the purpose of providing information about the Company to the public in Hong Kong and not for any other purposes. No investment decision should be based on the information contained in this document; (b) the publication of this document or supplemental, revised or replacement pages on the Exchange’s website does not give rise to any obligation of the Company, its sponsor, advisers or members of the underwriting syndicate to -

Rapid Urbanization in Eastern China: Roles for SEA

Rapid Urbanization in Eastern China: Roles for SEA Peter Mulvihill (York University) & Yangfan Li (Nanjing University) 1. Introduction In this paper we explore possibilities for an expanded role for Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) in addressing and preventing problems caused by rapid urbanization in coastal areas of China. 2. Context The torrid pace of economic development in many parts of China is well recognized, and its accompanying array of ecological and social impacts is increasingly well documented. Despite attempts to identify, avoid or minimize these negative effects through EIA, policy and related planning processes, irreversible impacts occur, often in cumulative ways that are not understood completely. This syndrome is particularly acute in China’s coastal regions, where rapid urbanization is transforming landscapes and ecosystems at an unprecedented pace. There is considerable hope that SEA can help improve planning and development processes, thus overcoming some of the characteristic shortcomings of more conventional forms of environmental assessment. The premise that SEA can be a proactive, sustainability-focused process is undeniably attractive. However, the gathering literature on SEA suggests strongly that there are still many implementation challenges to be overcome before this relatively new form of EA can reach its potential. SEA has been practiced in China since 2003. Bina (2008) has identified several recurring problems with the early implementation of SEA in China: it tends to be applied late in the planning process, and is therefore reactive to plans instead of influencing their formulation; like conventional project-driven EA, it is mostly mitigation-focused; there is little public participation; and there is a strong natural sciences and engineering bias in the process. -

According to Framework Directive 96/62/EC, Preliminary Assessment As a Tool for Air Quality Monitoring Network Design in a Chinese City

According to Framework Directive 96/62/EC, preliminary assessment as a tool for Air Quality Monitoring Network Design in a Chinese city I. Allegrini1, C. Paternò1, M. Biscotto1, W. Hong2, F. Liu2, Z. Yin2 & F. Costabile1 1Institute for Atmospheric Pollution, Italian National Research Council, Rome, Italy 2Environmental Monitoring Centre, Suzhou, P.R. China Abstract In the framework of the Sino-Italian Program in which the Italian Ministry of Environment and Territory is participating, an Air Quality Monitoring System in the City of Suzhou (China) was implemented by the Institute for Atmospheric Pollution of the Italian National Research Council (CNR-IIA). As stated in Framework Directive 96/62/EC, preliminary assessment of air quality is a very important step in the identification of sites for fixed monitoring stations. To that end, 100 saturation stations, equipped with passive samplers for sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, ozone, ammonia and BTX (benzene, toluene and xylene), were set up. The concentration values of these pollutants, coming from three campaigns carried out in Suzhou, were represented and explored by using the Arcview 8.2 software with Geostatistical Analyst and Spatial Analyst extensions. The interpolation was carried out using the two most important interpolation models (Inverse Distance Weighting and Ordinary Kriging). With reference to each campaign, pollution maps related to each interpolation model and to each pollutant were produced. Finally, a map with the definitive siting of the fixed monitoring stations was produced. Keywords: air quality monitoring system, preliminary assessment, pollutant distribution maps, passive samplers. Air Pollution XII, C. A. Brebbia (Editor) © 2004 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISBN 1-85312-722-1 416 Air Pollution XII 1 Introduction Air Quality is one of the areas in which Europe has been most active in recent years. -

Journal of Chinese Architecture and Urbanism

Jiaanbieyuan new courtyard-garden housing in Suzhou Zhang Journal of Chinese Architecture and Urbanism 2019 Volume 1 Issue 1: 1-19 Research Article Jiaanbieyuan New Courtyard-Garden Housing in Suzhou: Residents’ Experiences of the Redevelopment Donia Zhang Neoland School of Chinese Culture, Canada Corresponding author: Donia Zhang, 11211 Yonge Street, Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada. L4S 0E9 Email: [email protected] Citation: Zhang D, 2019, Jiaanbieyuan New Courtyard-Garden Housing in Suzhou: Residents’ Experiences of the Redevelopment. Journal of Chinese Architecture and Urbanism, 1(1): 526. http://dx.doi.org/10.26689/jcau.v1i1.526 ABSTRACT Cultural vitality as the fourth pillar of sustainable development has been widely acknowledged, and vernacular architecture as a major part of a nation’s material culture has entered the cultural sustainability dialogue. This recognition demands that new housing design and development should honor a local or regional identity. This in-depth case study assesses the architectural, environmental, spatial, constructional, social, cultural, and behavioral aspects of the Jiaanbieyuan (“Excellent Peace Courtyard-Garden Housing Estate”) built in Suzhou, China, in 1998. The 500-unit Jiaanbieyuan is located close to two UNESCO World Cultural Heritage sites, the Canglang (“Surging Waves”) Pavilion and the Master-of- Nets Garden. It has attempted to recreate Suzhou’s traditional architecture and landscape architecture. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected through numerous research methods, including onsite surveys and interviews. The findings show the new housing forms do not promote social relations as effectively as the traditional housing of the past. Moreover, the communal Central Garden has functioned to some extent as a social and cultural activity space. -

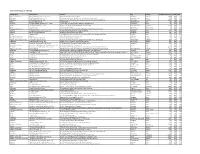

W20 Burton Active Factory Report FLA Factory Updates

Burton Active Factory List - May 2019 Category(ies) Factory Name Address City Country Production Workers Female Male Apparel, Outerwear Bacgiang Bgg Garment Corporation 349 # Giap Hai Road # Dinh K Ward Bac Giang Vietnam 3500 80% 20% Outerwear Bin Hai Super Apparel Co.,Ltd. Private Enterprise Park, Bin Hai County, Dong Kan Town,Jiangsu Dong Kan Town China 280 90% 10% Outerwear Bo Hsing Enterprise Co. Ltd. Lot No2 National Way1a Hoa Phu Industrial Zone, Hoa Phu Ward.Long Ho Dist. Vinh Long Vietnam 1949 74% 26% Socks Calzificio Telemaco Srl Via Brentella 9 Trevignano/TV Italy 18 50% 50% Bindings Chongqing Metaline Plastic Co.,Limited 1 South Way, Banqiao Industrial Estate Rongchang District Chong Qing China 50 60% 40% Gloves CPCG International Co., Ltd. Phum Chhok, Khum Kok Rovieng, Sruk Chhoeung Brey Kampong Cham Cambodia 1040 85% 15% Boards Craig's Boards 152 Industrial Parkway Burlington United States 10 10% 90% Hardgood Accessories Dominator Wax 20 Privilege Street, Woonsocket Ri, 02895,Woonsocket,Rhode Island,Usa Woonsocket United States 6 33% 67% Helmets Dongguan Upmost Industrial Co. Ltd. No.268,Yinhebei Road, Xinan Village, Shijie Town Dongguan China 497 47% 53% Helmets Eon Sporting Goods Co Ltd Building A, Qisha Industrial Park, Qisha, Dongguan China 408 45% 55% Boards Freesport Corp 158 Haung Pu Jiang S. Rd. Kunshan Economic And Technical Development Zone Kunshan China 73 35% 65% Hardgood Accessories Fuko Inc. 799-2, Zhongshan Road, Shengan Dist Taichung Taiwan 285 68% 32% Hardgood Accessories G3 Genuine Guide Gear, Inc. 3771 Marine Way,Burnaby,Canada Burnaby Canada 31 26% 74% Apparel, Basic Fleece and Tees Gin-Sovann Fashion Limited Plov Lum, Krom 06, Phum Chres Sangkat Phnom Penh Thmey, Khan Sensok Phnom Penh Cambodia 860 91% 9% Headwear Greatmall Thien Phu Co., Ltd Zone 2 - An Phu - Thuan An \, Binh Duong,Vietnam Binh Duong Vietnam 107 86% 14% Headwear Hangzhou U-Jump Art & Crafts Co Ltd 31 Tangkang Road, Chongxian Street, Yuhang District Hangzhou China 285 80% 20% Basic Fleece and Tees Hialpesa S.A.: Hilanderia De Algodon Peruano S.A Av. -

Wuzhou International Holdings Limited

WUZHOU INTERNAT WUZHOU INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS LIMITED 五洲國際控股有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) I ONAL Stock code: 01369 H ANNUAL REPORT 2014 OLD I NG S LI M I TED ANNUAL REPORT 2014 ANNUAL RESPONSIBLE REAL ESTATE Healthy Commercial Business Contents 2 Corporate Information 6 Financial Highlights 7 Highlights of the Year 10 Honours and Awards 13 Social Responsibilities 14 Chairman’s Statement 20 Management Discussion and Analysis Business Review Financial Review 39 Directors’ Profile 43 Senior Management’s Profile 45 Report of the Directors 55 Corporate Governance Report 62 Independent Auditors’ Report 64 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 65 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 67 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 68 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 70 Statement of Financial Position 71 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 164 Financial Summary 165 Major Investment Properties held by the Group Wuzhou International Holdings Limited 002 Annual Report 2014 CORPORATE INFORMATION DIRECTORS AUDITORS Executive Directors Ernst & Young Mr. Shu Cecheng (Chairman) Certified Public Accountants Mr. Shu Cewan (Chief Executive Officer) Mr. Shu Ceyuan COMPLIANCE ADVISOR Ms. Wu Xiaowu Octal Capital Limited Mr. Zhao Lidong PRINCIPAL BANKERS Non-Executive Director Mr. Wang Wei (appointed on 26 September 2014) Bank of China Limited Bank of Communications Co., Ltd Independent Non-Executive Directors Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited Dr. Song Ming Xiamen International Bank Mr. Lo Kwong Shun, Wilson Prof. Shu Guoying LEGAL ADVISORS COMPANY SECRETARY As to Hong Kong Law Shearman & Sterling Mr. Cheung Man Hoi (appointed on 30 June 2014) As to PRC Law AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVES Global Law Office Mr.