History & Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

A Brief Survey of Missions

2 A Brief Survey of Missions A BRIEF SURVEY OF MISSIONS Examining the Founding, Extension, and Continuing Work of Telling the Good News, Nurturing Converts, and Planting Churches Rev. Morris McDonald, D.D. Field Representative of the Presbyterian Missionary Union an agency of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA P O Box 160070 Nashville, TN, 37216 Email: [email protected] Ph: 615-228-4465 Far Eastern Bible College Press Singapore, 1999 3 A Brief Survey of Missions © 1999 by Morris McDonald Photos and certain quotations from 18th and 19th century missionaries taken from JERUSALEM TO IRIAN JAYA by Ruth Tucker, copyright 1983, the Zondervan Corporation. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, MI Published by Far Eastern Bible College Press 9A Gilstead Road, Singapore 309063 Republic of Singapore ISBN: 981-04-1458-7 Cover Design by Charles Seet. 4 A Brief Survey of Missions Preface This brief yet comprehensive survey of Missions, from the day sin came into the world to its whirling now head on into the Third Millennium is a text book prepared specially by Dr Morris McDonald for Far Eastern Bible College. It is used for instruction of her students at the annual Vacation Bible College, 1999. Dr Morris McDonald, being the Director of the Presbyterian Missionary Union of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA, is well qualified to write this book. It serves also as a ready handbook to pastors, teachers and missionaries, and all who have an interest in missions. May the reading of this book by the general Christian public stir up both old and young, man and woman, to play some part in hastening the preaching of the Gospel to the ends of the earth before the return of our Saviour (Matthew 24:14) Even so, come Lord Jesus Timothy Tow O Zion, Haste O Zion, haste, thy mission high fulfilling, to tell to all the world that God is Light; that He who made all nations is not willing one soul should perish, lost in shades of night. -

United Methodist Bishops Page 17 Historical Statement Page 25 Methodism in Northern Europe & Eurasia Page 37

THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA BOOK of DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2009 Copyright © 2009 The United Methodist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may reproduce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Northern Europe & Eurasia Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2009. Copyright © 2009 by The United Method- ist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. Used by permission.” Requests for quotations that exceed 1,000 words should be addressed to the Bishop’s Office, Copenhagen. Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. Name of the original edition: “The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church 2008”. Copyright © 2008 by The United Methodist Publishing House Adapted by the 2009 Northern Europe & Eurasia Central Conference in Strandby, Denmark. An asterisc (*) indicates an adaption in the paragraph or subparagraph made by the central conference. ISBN 82-8100-005-8 2 PREFACE TO THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA EDITION There is an ongoing conversation in our church internationally about the bound- aries for the adaptations of the Book of Discipline, which a central conference can make (See ¶ 543.7), and what principles it has to follow when editing the Ameri- can text (See ¶ 543.16). The Northern Europe and Eurasia Central Conference 2009 adopted the following principles. The examples show how they have been implemented in this edition. -

Introduction

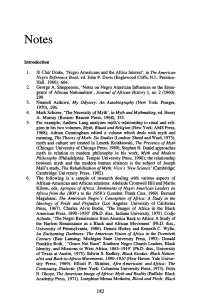

Notes Introduction 1. StClair Drake, 'Negro Americans and the Africa Interest', in The American Negro Reference Book, ed. John P. Davis (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1966), 664. 2. George A. Shepperson, 'Notes on Negro American Influences on the Emer gence of African Nationalism', Journal of African History 1, no. 2 (1960): 299. 3. Nnamdi Azildwe, My Odyssey: An Autobiography (New York: Praeger, 1970), 196. 4. Mark Schorer, 'The Necessity of Myth', in Myth and Mythmaking, ed. Henry A. Murray (Boston: Beacon Press, 1968), 355. 5. For example, Andrew Lang analyzes myth's relationship to ritual and reli gion in his two volumes, Myth, Ritual and Religion (New York: AMS Press, 1968); Adrian Cunningham edited a volume which deals with myth and meaning, The Theory of Myth: Six Studies (London: Sheed and Ward, 1973); myth and culture are treated in Leszek Kolakowski, The Presence of Myth (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989); Stephen H. Daniel approaches myth in relation to modern philosophy in his work, Myth and Modem Philosophy (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990); the relationship between myth and the modern human sciences is the subject of Joseph Mali's study, The Rehabilitation of Myth: Vico's 'New Science' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). 6. The following is a sample of research dealing with various aspects of African-American and African relations: Adelaide Cromwell Hill and Martin Kilson, eds, Apropos of Africa: Sentiments of Negro American Leaders on Africa from the 1800's to the 1950's (London: Frank Cass, 1969). Bernard Magubane, The American Negro's Conception of Africa: A Study in the Ideology of Pride and Prejudice (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967). -

The Book of Discipline

THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH “The Book Editor, the Secretary of the General Conference, the Publisher of The United Methodist Church and the Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision shall be charged with edit- ing the Book of Discipline. The editors, in the exercise of their judgment, shall have the authority to make changes in wording as may be necessary to harmonize legislation without changing its substance. The editors, in consultation with the Judicial Coun- cil, shall also have authority to delete provisions of the Book of Discipline that have been ruled unconstitutional by the Judicial Council.” — Plan of Organization and Rules of Order of the General Confer- ence, 2016 See Judicial Council Decision 96, which declares the Discipline to be a book of law. Errata can be found at Cokesbury.com, word search for Errata. L. Fitzgerald Reist Secretary of the General Conference Brian K. Milford President and Publisher Book Editor of The United Methodist Church Brian O. Sigmon Managing Editor The Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision Naomi G. Bartle, Co-chair Robert Burkhart, Co-chair Maidstone Mulenga, Secretary Melissa Drake Paul Fleck Karen Ristine Dianne Wilkinson Brian Williams Alternates: Susan Hunn Beth Rambikur THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House Nashville, Tennessee Copyright © 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may re- produce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2016. -

United Methodist Bishops Ordination Chain 1784 - 2012

United Methodist Bishops Ordination Chain 1784 - 2012 General Commission on Archives and History Madison, New Jersey 2012 UNITED METHODIST BISHOPS in order of Election This is a list of all the persons who have been consecrated to the office of bishop in The United Methodist Church and its predecessor bodies (Methodist Episcopal Church; Methodist Protestant Church; Methodist Episcopal Church, South; Church of the United Brethren in Christ; Evangelical Association; United Evangelical Church; Evangelical Church; The Methodist Church; Evangelical United Brethren Church, and The United Methodist Church). The list is arranged by date of election. The first column gives the date of election; the second column gives the name of the bishop. The third column gives the name of the person or organization who ordained the bishop. The list, therefore, enables clergy to trace the episcopal chain of ordination back to Wesley, Asbury, or another person or church body. We regret that presently there are a few gaps in the ordination information, especially for United Methodist Central Conferences. However, the missing information will be provided as soon as it is available. This list was compiled by C. Faith Richardson and Robert D. Simpson . Date Elected Name Ordained Elder by 1784 Thomas Coke Church of England 1784 Francis Asbury Coke 1800 Richard Whatcoat Wesley 1800 Philip William Otterbein Reformed Church 1800 Martin Boehm Mennonite Society 1807 Jacob Albright Evangelical Association 1808 William M'Kendree Asbury 1813 Christian Newcomer Otterbein 1816 Enoch George Asbury 1816 Robert Richford Roberts Asbury 1817 Andrew Zeller Newcomer 1821 Joseph Hoffman Otterbein 1824 Joshua Soule Whatcoat 1824 Elijah Hedding Asbury 1825 Henry Kumler, Sr. -

THE BOOK of DISCIPLINE of the UNITED METHODIST CHURCH CONS001936QK001.Qxp:QK001.Qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page Ii

CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page i THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page ii “The Book Editor, the Secretary of the General Conference, the Pub- lisher of The United Methodist Church, and the Committee on Corre- lation and Editorial Revision shall be charged with editing the Book of Discipline. The editors, in the exercise of their judgment, shall have the authority to make changes in wording as may be necessary to harmonize legislation without changing its substance. The editors, in consultation with the Judicial Council, shall also have authority to delete provisions of the Book of Discipline that have been ruled uncon- stitutional by the Judicial Council.” —Plan of Organization and Rules of Order of the General Confer- ence, 2008 See Judicial Council Decision 96, which declares the Discipline to be a book of law. Errata can be found at Cokesbury.com, word search for Errata. L. Fitzgerald Reist Secretary of the General Conference Neil M. Alexander Publisher and Book Editor of The United Methodist Church Judith E. Smith Executive Editor Marvin W. Cropsey Managing Editor The Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision Eradio Valverde, Chairperson Richard L. Evans, Vice Chairperson Annie Cato Haigler, Secretary Naomi G. Bartle CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page iii THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2008 The United Methodist Publishing House Nashville, Tennessee CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page iv Copyright © 2008 The United Methodist Publishing House. -

FULL ISSUE (48 Pp., 2.3 MB PDF)

Vol. 12, No.4 nternatlona• October 1988 etln• Modernity and the Everlasting Gospel: Assessing the Newbigin Thesis n March 1984 Bishop Lesslie Newbigin, in his Warfield world are always reading cultural self-analyses. Newbigin I Lectures at Princeton Theological Seminary, proposed a has come with the insight of an outsider." thesis that continues to challenge mission thinkers. The forces of Two highly practical articles follow-on the use of computers modernity, Newbigin declares, have produced in the West one in mission research, and on the need for precautionary prepa of the most pressing mission situations of all. What was once ration by mission communities to cope with threats of terrorism. known as Christendom has become "a pagan society whose Christian G. Baeta offers his personal story in our "Pil public life is ruled by beliefs which are false." (See "Can the grimage in Mission" series; and Paul Rowntree Clifford in our West Be Converted?" International Bulletin of Missionary Research, "Legacy" series highlights the pervasive influence of Norman January 1987.) Goodall in the London Missionary Society, the International Mis In this issue, David M. Stowe keys his critique of the New sionary Council, and the wider ecumenical movement. bigin thesis to the question, "What interpretation of the ever It remains profoundly true that mission issues are never fi lasting gospel communicates most effectively" in modern West nally solved, but must be reassessed by each generation. Dia ern culture? The Newbigin thesis, Stowe writes, fails to credit the logues such as found in the opening pages of this issue can help work of God's Spirit in producing the "humanist consensus" restate for our day the essential relation between the claims of and the "democratic consensus." These developments enable the gospel and the worlds of culture. -

108303D So Long, Joey 11109D Passover 124659D

videonum title 108303D So Long, Joey 11109D Passover 124659D All About Jesus (Who Is This Jesus? / What if Jesus Had Never Been Born? Set) 16352D Three Miracles of Happiness 16932D Why Be Catholic? 17496D You're a Better Parent Than You Think 200230D George Washington Carver: An Uncommon Way 30762D Dale Evans: Beyond the Happy Trails 40587D Wisdom From Above - Deacon Alex Jones 406830D King of Glory 4616D China Cry 4623D Martin Luther 4636D Paul The Emissary 4637D Stephen's Test Of Faith 4638D Bonhoeffer: Agent Of Grace 4652D Touch Of The Master's Hand 4653D People Who Met Jesus - Series I 4654D Revolutionary: Epic Version 4671D Visit To The Sepulcher 4683D The Amish: A People Of Preservation 4702D Sue Thomas: Breaking the Sound Barrier 4703D Glory To God Alone: Life Of J.S. Bach 4709D Little Shepherd 4727D Saints And Strangers 4728D Going Home: The Journey Of Kim Jones 4729D The First Valentine 4730D Three Christmas Classics 4733D The Fanny Crosby Story 4737D God's Outlaw: The Story Of William Tyndale 4746D Bless You Prison 4756D Jeremy’s Egg 4761D Genesis With Max McLean 4772D Dateline Jerusalem 4777D The Cross And The Switchblade - Asian Version 4779D Run Baby Run 4782D Candle In The Dark 4783D John Hus 4784D Red Boots For Christmas 4790D Beyond The Next Mountain 4792D The Seven Churches Of Revelation Rediscovered 4800D Mama Heidi 4802D Christopher Columbus 4804D The Radicals 4807D Bethlehem Year Zero 4808D John Wycliffe: The Morningstar 4809D Reality 4811D The Last Supper 4812D John Wesley Biography 4813D Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis 4817D In The Arms Of Angels 4818D Great Mr.