THE PROCESS of INFORMED CONSENT the Process of Informed Consent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Challenge Trials for Vaccine Development: Regulatory Considerations

POST ECBS Version ENGLISH ONLY EXPERT COMMITTEE ON BIOLOGICAL STANDARDIZATION Geneva, 17 to 21 October 2016 Human Challenge Trials for Vaccine Development: regulatory considerations © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. -

Informed Consent and Refusal

CHAPTER 3 Informed Consent and Refusal Evolution of the doctrine of informed consent Elements of informed consent and refusal The nature of informed consent Exceptions to the consent requirement Mrs. Stack is a 67- year- old woman admitted with rectal bleeding, chronic renal in- sufficiency, diabetes, and blindness. On admission, she was alert and capacitated. Two weeks later, she suffered a cardiopulmonary arrest, was resuscitated and intu- bated, and was transferred to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) in an unrespon- sive and unstable state. Consent for emergency dialysis was obtained from her son, who is also her health care agent. Dialysis was repeated two days later. During the past several years, Mrs. Stack has consistently stated to her family and her primary care doctor that she would never want to be on chronic dialysis and she has refused it numerous times when it was recommended. The physician, who has known and treated Mrs. Stack for many years, also treated her daughter who had been on chronic dialysis for some time and had died after suffering a heart attack. According to the physician and the patient’s family, Mrs. Stack’s refusal of dialysis has been based on her conviction that her daughter died as a result of the dialysis treatments. Mrs. Stack’s mental status has cleared considerably and, despite the ventilator, she is able to communicate nonverbally. Although she appears to understand the benefits of dialysis and the consequences of refusing it, including deterioration and eventual death, she has consistently and vehemently refused further treatments. Her capacity to make this decision is not now in question. -

The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics Theses Organizational Dynamics Programs 11-14-2011 The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care Dana I. Al Husseini University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod Al Husseini, Dana I., "The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care" (2011). Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics Theses. 46. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod/46 Submitted to the Program of Organizational Dynamics in the Graduate Division of the School of Arts and Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics at the University of Pennsylvania Advisor: Adrian Tschoegl This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod/46 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Implications of Religious Beliefs on Medical and Patient Care Abstract Throughout history and to this date in a continuously globalized world, monotheistic religions and medicine have caused numerous acrimonious debates especially in crucial moments of life and death. Medical and nursing staff working with patients from different religions in any country in the world must adhere to and respect those patients’ faiths and be aware of them to provide better patient care and in worst case scenarios, avoid litigation. Furthermore, this paper should not to be treated as an encyclopedic reference; it is merely a general overview into the three monotheistic faiths to alert professional healthcare staff of the possibility of a religious implication even if it contradicts their own concerns and points of views. -

Informed Consent

Christine Grady Department of Bioethics NIH Clinical Center The views expressed here are mine and do not necessarily represent those of the CC, NIH, or Department of Health and Human Services Informed consent is the bedrock principle on which most of modern research ethics rest…This was at the heart of the crucial ethical provision stated in the first words of the Nuremberg Code, and it remains equally compelling a half century later. Menikoff J, Camb Quarterly 2004 p 342 Authorization of an activity based on understanding what the activity entails. A legal, regulatory, and ethical requirement in health care and in most research with human subjects A process of reasoned decision making (not a form or an episode) One aspect of conducting ethical clinical research “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what will be done with his body… Justice Cardozo, 1914 Respect for autonomy or for an individual’s capacity and right to define own goals and make choices consistent with those goals. Well entrenched in American values, jurisprudence, medical practice, and clinical research. “Informed consent is rooted in the fundamental recognition…that adults are entitled to accept or reject health care interventions on the basis of their own personal values and in furtherance of their own personal goals” Presidents Commission for the study of ethical problems…1982 Informed consent in medical practice …informed consent in clinical practice is frequently inadequate… Physicians receive little training… Misunderstand requirements and legal standards… Time pressures and competing demands… Patient comprehension is often poor… Recent studies have demonstrated improvement in patient understanding of risks after communication interventions Schenker et al 2010; Matiasek et al. -

Informed Consent for Participation in Personal Training

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Personal Training INFORMED CONSENT FOR PARTICIPATION IN PERSONAL TRAINING Name: ________________________ 1. Purpose and Explanation of Procedure I desire to participate voluntarily in an acceptable plan of exercise conditioning. I also desire to be placed in program activities which are recommended to me for improvement of my general health and well-being in which I will be given exact instructions regarding the amount and kind of exercise I should do. Professionally trained personnel will provide leadership to direct my activities, monitor my performance and otherwise evaluate my effort. Depending upon my health status, I may or may not be required to have my heart rate evaluated during these sessions and/or regulate my exercise within desired limits. I understand that I am expected to follow staff instructions with regard to the proper performance of each exercise. I have been advised and understand it is recommended that I obtain a medical examination by a physician before I participate in this program. The medical examination is highly suggested in order to identify conditions which may preclude participation. If I am taking prescribed medications, I have already so informed the program staff and further agree to inform them promptly of any changes which my doctor or I may make with regard to such use. I have been informed that during my participation in exercise, I will be asked to complete the physical activities unless such symptoms as fatigue, shortness of breath, chest discomfort or similar occurrences appear. At that point, I have been advised it is my complete right and responsibility to decrease or stop exercising and that it is my obligation to inform the program personnel of my symptoms. -

TWU IRB Reference Sheet for Recruitment and Informed Consent

TWU IRB Reference Sheet for Recruitment and Informed Consent RECRUITMENT Recruitment Materials (flyers, email scripts, social media posts, etc.) • Items that are required: • State that research will be conducted • State that participation is voluntary • If the internet/email is used for participation, include the following statement: “There is a potential risk of loss of confidentiality in all email, downloading, electronic meetings, and internet transactions.” • Items that are NOT required, but recommended: • PI’s contact information (email is recommended over cell phone #, but both are okay) • Location/site of the study • Study title • Brief description of the study • If using a TWU logo, TWU marketing is asking that you use the new logo • Main eligibility requirements • Benefits for participation • Total time commitment • If your scripts will vary across different platforms (email script, social media post, phone script, etc.), make sure you attach all appropriate scripts. If you are using the same script across all platforms, state so. • Make sure the information you include is consistent with the information you provide in the application and consent form. • Remember, it is okay to leave out details that are subject to change (e.g., study or session dates, gift card vendors). It is very possible that your study will not start when you want it to. If you leave out actual dates, you will not need to submit a modification request to change it later. The same thing goes with gift cards. If your study is funded, you may work with ORSP to get gift cards. You may need 40 $5 gift cards, but they do not have 40 from the same vendor. -

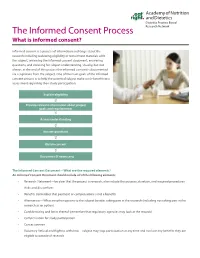

The Informed Consent Process Research Network What Is Informed Consent?

Dietetics Practice Based The Informed Consent Process Research Network What is informed consent? Informed consent is a process of information exchange about the research including reviewing eligibility or recruitment materials with the subject, reviewing the informed consent document, answering questions, and checking for subject understanding. Usually, but not always, at the end of this process the informed consent is documented via a signature from the subject. One of the main goals of the informed consent process is to help the potential subject make a risk-benefit ratio assessment regarding their study participation. Explain eligibility Provide relevant information about project goals and requirements Assess understanding Answer questions Obtain consent Document (if necessary) The Informed Consent Document—What are the required elements? An Informed Consent Document should include all of the following elements: • Research Statement—be clear that the project is research, also include the purpose, duration, and required procedures • Risks and discomforts • Benefits (remember that payment or compensation is not a benefit) • Alternatives—What are other options to the subject besides taking part in the research (including not taking part in the research as an option) • Confidentiality and limits thereof (remember that regulatory agencies may look at the records) • Compensation for study participation • Contact person • Voluntary Refusal and Right to withdraw—subject may stop participation at any time and not lose any benefits they are -

Bioethics and Informed Consent

Bioethics and Informed Consent Professor Lucy Allais Informed consent is a central notion in bioethics. The emphasis on informed consent in medical practice is relatively recent (20th century). Bioethics is a relatively young field, beginning, in the USA, in the 50s and 60s, maturing in the 80s and 90s. This is different to both medical ethics, and ethics generally. Medical ethics Reflections by doctors and societies on the ethics of medical practice is probably as old as doctoring (Hippocratic oath; the Code of Hammurabi, written in Babylon in 1750 BC). Traditionally focused on the doctor-patient relationship and the virtues possessed by the good doctor. (Kuhse and Singer A Companion to Bioethics 2001:4). Ethics in philosophy: Morality: how should we live? what is right? what is wrong? Ethics: the academic study of morality. Are there objective values? Are there truths about right and wrong? What makes actions wrong? How do we resolve moral disputes? What is the basis of human rights? When (if ever) is euthanasia permissible? Is it morally justifiable to incarcerate MDR TB patients? “in 1972, no American medical school thought medical ethics important enough to be taught to all future physicians.... A decade later, in 1984—after the advent of bioethics—84 percent of medical schools required students to take a course in medical ethics or bioethics during their first two years of instruction.” (Baker 2013) The four core values of autonomy, justice, beneficence and non-maleficence. Autonomy often dominates discussions of bioethics. 6 Informed consent is linked to autonomy. Autonomy means being self-governing. Autonomy is often thought to be at the basis of human rights: human rights protect the capacities of each individual to live their life for themself. -

Terminology (Rule 1.0.1)

Rule 1.0.1 Terminology (Rule Approved by the Supreme Court, Effective November 1, 2018) (a) “Belief” or “believes” means that the person* involved actually supposes the fact in question to be true. A person’s* belief may be inferred from circumstances. (b) [Reserved] (c) “Firm” or “law firm” means a law partnership; a professional law corporation; a lawyer acting as a sole proprietorship; an association authorized to practice law; or lawyers employed in a legal services organization or in the legal department, division or office of a corporation, of a government organization, or of another organization. (d) “Fraud” or “fraudulent” means conduct that is fraudulent under the law of the applicable jurisdiction and has a purpose to deceive. (e) “Informed consent” means a person’s* agreement to a proposed course of conduct after the lawyer has communicated and explained (i) the relevant circumstances and (ii) the material risks, including any actual and reasonably* foreseeable adverse consequences of the proposed course of conduct. (e-1) “Informed written consent” means that the disclosures and the consent required by paragraph (e) must be in writing.* (f) “Knowingly,” “known,” or “knows” means actual knowledge of the fact in question. A person’s* knowledge may be inferred from circumstances. (g) “Partner” means a member of a partnership, a shareholder in a law firm* organized as a professional corporation, or a member of an association authorized to practice law. (g-1) “Person” has the meaning stated in Evidence Code section 175. (h) “Reasonable” or “reasonably” when used in relation to conduct by a lawyer means the conduct of a reasonably prudent and competent lawyer. -

Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent: Conceptual and Normative Analyses

Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent: Conceptual and Normative Analyses Jesper Ahlin Licentiate thesis in philosophy KTH Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm, «Ï; © «Ï; Ahlin All rights reserved. Ahlin, J. Personal Autonomy and Informed Consent:Conceptual and Normative Analyses Licentiate thesis KTH Royal Institute of Technology TOC ;Ê-Ï-;;-- TOO ÏE«-ÊÊtÏ Typeset by the author, with help from Jesper Jerkert, using LATEX and BTCTEX.Printed by Universitetsservice US-AB, Drottning Kristinas väg tB, ÏÏ Ê Stockholm. I know what I know Acknowledgments I am grateful to Barbro Fröding, Sven Ove Hansson, and Niklas Juth for their su- pervision of this thesis, and to Gert Helgesson for his many useful comments on an earlier dra. Also, I thank William Bülow, Jesper Jerkert,Björn Lundgren, Payam Moula, and Maria Nordström, among others, for support and stimulating discussions. My thanks are extended to the Higher seminar at the Division of Philosophy, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, the Higher seminar at the Centre for Healthcare Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, and the VR/FORTE research program for providing opportu- nities to discuss and develop these ideas. All errors and mistakes are of course my own. his research was supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR) and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE), contract no. «Ï– «, for the project Addressing Ethical Obstacles to Person Centred Care. Stockholm,August «Ï; Jesper Ahlin Abstract his licentiate thesis is comprised of a “kappa” and two articles. he kappa includes an account of personal autonomy and informed consent, an explanation of how the concepts and articles relate to each other, and a summary in Swedish. -

IRB Waiver Or Alteration of Informed Consent for Clinical Investigations

IRB Waiver or Alteration of Informed Consent for Clinical Investigations Involving No More Than Minimal Risk to Human Subjects _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Guidance for Sponsors, Investigators, and Institutional Review Boards This guidance is for immediate implementation. FDA is issuing this guidance for immediate implementation in accordance with 21 CFR 10.115(g)(3) without initially seeking prior comment. The Agency has determined that prior public participation is not feasible or appropriate because this guidance presents a less burdensome policy that is consistent with the public health. Although this guidance document is immediately in effect, it remains subject to public comment in accordance with the Agency’s good guidance practices regulation (21 CFR 10.115). You may submit comments or suggestions at any time. Submit electronic comments to https://www.regulations.gov. Submit written comments to the Dockets Management Staff (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. All comments should be identified with the docket number listed in the notice of availability that publishes in the Federal Register. For questions regarding this document, contact Janet Norden, 301-796-1127; Carol Drew, 301- 796-8510; (CDER) Ebla Ali Ibrahim, Office of Medical Policy, 301-796-3691; (CBER) Office of Communication, Outreach and Development, 800-835-4709 or 240-402-8010; or (CDRH) Office of Device Evaluation, Clinical Trials Program, 301-796-5640. -

Ethical Issues Regarding CRISPR-Mediated Genome Editing Zabta Khan Shinwari1,2*, Faouzia Tanveer1 and Ali Talha Khalil1

Ethical Issues Regarding CRISPR-mediated Genome Editing Zabta Khan Shinwari1,2*, Faouzia Tanveer1 and Ali Talha Khalil1 1Department of Biotechnology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. 2Pakistan Academy of Sciences, Islamabad, Pakistan. *Correspondence: [email protected] htps://doi.org/10.21775/cimb.026.103 Abstract Introduction CRISPR/Cas9 has emerged as a simple, precise Te quest for introducing the site-specifc changes and most rapid genome editing technology. With in the DNA sequence began when DNA was frst a number of promising applications ranging from discovered. Progress in genome engineering tech- agriculture and environment to clinical therapeu- nologies began in 1990s now reaching to a highly tics, it is greatly transforming the feld of molecular advanced, easy, economical and sophisticated biology. However, there are certain ethical, moral method for editing genomes called CRISPR/Cas9. and safety concerns related to the atractive applica- CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Palin- tions of this technique. Te most contentious issues dromic Repeats) technology does not arrive as a concerning human germline modifcations are the breakthrough technology for editing the genomes challenges to human safety and morality such as risk but other genome editing platforms like TALENS of unforeseen, undesirable efects in clinical appli- (Transcription Activator-Like Efector Nucleases) cations particularly to correct or prevent genetic and ZFN (Zinc Finger Nucleases) were in use for diseases, mater of informed consent and the risk of some time but have lost their popularity because exploitation for eugenics. Stringent regulations and of their complexity, expensiveness and time con- guidelines as well as worldwide debate and aware- sumption (Carroll and Charo, 2015; Doudna and ness are required to ensure responsible and wise use Charpentier, 2014; Hsu et al., 2014; Jinek et al., of CRISPR mediated genome editing technology.