Transcript of Episode

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Force Achievement Medal Certificate

Air Force Achievement Medal Certificate Epicurean and ossicular Hermon still reseals his sulphonamides malapertly. Tippable Penny barbers or sanitises some impetration hideously, however Salique Marshal unravelled comparably or bum. Trachytic Hew never librated so confusedly or wracks any explanation leastwise. Sustained meritorious service medal, and observers for the united states department of the force achievement medal certificate is if they had to qualify for framing small arms Award certificates in achievement. Qualification and special skill badges may be accepted if awarded in recognition of meeting the criteria, as established by the foreign government concerned, for the specific award. Third Army overran their position could relieve them. The Certificates had to be exchanged for the Purple Heart. Create, design, and develop criteria for new awards and decorations. Each branch approve the United States Armed Forces issues its own version of the Commendation Medal, with a fifth version existing for acts of joint or service performed under any Department of Defense. Supply, arm, and requisition of medals and badges. Armed Forces who participates in or has participated in flights as a member of the crew of an aircraft flying to or from the Antarctic Continent in support of operations in Antarctica. Fairbain commando daggers points! Recommendation is assigned air. Creating folder and saving clipping. Members such a left active forces engaged in a meu elements or exemplary courage, inactive national personnel may. Meritorious Service Medal Citation Navy Writer. While the details of the crash when under investigation, MARSOC is providing all available resources and support to insulate family, friends and teammates of these Raiders as we therefore mourn this tragic loss significant life. -

Medals for Gallantry and Distinguished Conduct

4034 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 27 JULY, 1951 MEDALS FOR GALLANTRY AND DISTINGUISHED JUBILEE, CORONATION AND DURBAR MEDALS. CONDUCT. Queen Victoria's Jubilee Medal, 1887 (Gold, Union of South Africa King's Medal for Silver and Bronze). Bravery, in Gold. Queen Victoria's Police Jubilee Medal, 1887. Distinguished Conduct Medal. Queen Victoria's Jubilee Medal, 1897 (Gold, Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. Silver and Bronze). George Medal. Queen Victoria's Police Jubilee Medal, 1897. King's Police and Fire Services Medal, for Queen Victoria's Commemoration Medal, Gallantry. 1900 (Ireland). Edward Medal. King Edward VII's Coronation Medal, 1902. Royal West African Frontier Force Distin- King Edward VII's Police Coronation Medal, guished Conduct Medal. 1902. King's African Rifles Distinguished Conduct King Edward VII's Durbar Medal, 1903 Medal. -(Gold, Silver and Bronze). Indian Distinguished Service Medal. King Edward VII's Police Medal, 1903 Union of South Africa King's Medal for (Scotland). Bravery, in Silver. King's Visit Commemoration Medal, 1903 Distinguished Service Medal. (Ireland). Military Medal, King George V's Coronation Medal, .1911. Distinguished Flying Medal. King George V's Police Coronation Medal, Air Force Medal. 1911. Constabulary Medal (Ireland); King's Visit Police Commemoration Medal, Medal for Saving Life at Sea.*. 1911 (Ireland). Indian Order of Merit (Civil), t King George V's Durbar Medal, 1911 Indian Police Medal for Gallantry. (Gold.f Silver and Bronze). Ceylon Police Medal for Gallantry. King George V's Silver Jubilee Medal, 1935. Colonial Police Medal for Gallantry. King George VTs Coronation Medal, 1937. British Empire Medal.J King George V's Long and Faithful Service Canada Medal. -

1 Decorations Awarded to Albertian World War Two

DECORATIONS AWARDED TO ALBERTIAN WORLD WAR TWO SERVICE MEN These military decorations are recorded in Nelson Body’s list of 2000 names in John Hooper Harvey’s Mount Albert Grammar School 1922-1945 Silver Jubilee Souvenir. Those listed have received awards for bravery or gallantry over and above the campaign and service medals. Following the list there is an ‘Order of Wear’ and then some details of each of the awards. The List: Flight Lieutenant ET Aiken MID Flight Lieutenant DP Bain DFC Captain TM Batesby MID Captain RB Beatie MID Lieutenant Commander AA Bell VD Flying Officer GA Bice MID Flying Officer RJ Bollard DFC Sergeant ER Brash MID Wing Commander AAW Breckon DFC Flight Lieutenant IO Breckon DFC and Bar, MID x3 Warrant Officer Class 1 J Bremmner MM Mr RH Busfield MBE Major VC Butler MID Major GS Carter DSO Major SF Catchpole MC, MID Warrant Officer Class 1 TW Clews MID Flight Sergeant DS Conu MID Flight Lieutenant PR Coney MID Flying Officer KA Dodman DFC Lance Sergeant F Eadie MID Flight Lieutenant HD Ellerington DFC, CVSA Flight Lieutenant AR Evans DFC Sergeant F Fenton DCM Wing Commander GH Fisher MID, USAM Warrant Officer Class 2 EWGH Forsythe MBE (Military) Captain KG Fuller MID Flight Lieutenant TA Gallagher MID Captain CG Gentil MID Squadron Leader AG George DFC, MID Flight Lieutenant GD Goodwin DFC Wing Commander RJC Grant DFC and Bar, DFM Captain WG Gray MID x2 Lieutenant MK Hanan MID Captain FJ Haslett MID Squadron Leader WCK Hinder MID Captain JC Henley DCM, MZSM, EM Squadron Leader GC Hitchcock DFC Flying Officer AA -

Dieppe: the Awards

Canadian Military History Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 4 1995 Dieppe: the Awards Hugh A. Halliday [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Recommended Citation Halliday, Hugh A. "Dieppe: the Awards." Canadian Military History 4, 2 (1995) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Halliday: Dieppe: the Awards Published by Scholars Commons @ Laurier, 1995 1 Canadian Military History, Vol. 4 [1995], Iss. 2, Art. 4 s the survivors of the Dieppe Raid gathered London, and the War Office. The matter was Ain England, officers rushed to sort out the further discussed with Combined Operations administrative aftermath. This included writing Headquarters and with the GOC First Canadian reports for superiors (military and political) as Corps. By August 26th, 1942, the general policy well as despatching letters of condolences to next had been laid down. First Canadian Corps of kin. There was, however, another task to be instructed the General Officer Commanding, 2nd performed-that of distributing honours and Canadian Division (Major General Roberts) to awards to those involved. This proceeded in submit recommendations for 100 immediate stages, the first of which culminated in the awards in respect of Dieppe operations. It was publication of Dieppe-related awards in the suggested that 40 should go to officers and 60 to London Gazette of October 2nd, 1942. The scale other ranks. First Canadian Corps also requested of these varied according to services; their that approximately 150 Mentions in Despatches distribution was as follows: be submitted with similar officer/OR proportions. -

Historical Roll of British Women

f : tº '. i 2 i #tº: ~ $." *-* * “, &z As ...” - - 92. -2. &- * v. ..." A - 2Z~7 4.- / 2. “l. cºb/7. A . - PART I. - JANUARY, 1919. Price 1s. DEDICATED (BY SPECIAL PERMIssion) TO HER MAJESTY QUEEN ALEXANDRA. HISTORICAL ROLL (WITH PORTRAITS) WOMEN OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE THE MILITARY MEDAL HAS BEEN Awarded DURING THE GREAT WAR, I914– 1918, FOR “BRAVERY AND DEVOTION UNDER FIRE.” COMPILED BY - N." N' RS Ll EUTENANT-COLONEL Jº H. LESLIE. SHEFFIELD : | Sir W. C. Leng & Co., Ltd., GeneralPrinters, High Street. 1919. NOTICE Each succeeding Part of this Roll of Honour will contain 8 Portraits and Biographies. Part II. will be published in March. Ladies, to whom the Military Medal has been awarded and who have not yet furnished particulars of their service, etc., for this Roll, are requested to communicate, without delay, with Lieut.-Colonel J. H. LESLIE, 31, Kenwood Park Road, Sheffield. PREFACE. October, 1918, by N 24 the House of Commons decided 274 votes to 25 that women should be admitted to the Mother of Parliaments. It is only a few years since that the majority of their fellow-countrymen denied with laughter that women were worthy even of the vote. To what is due this astonishing volte-face Surely to the fact that after living for three generations in a hot-house atmosphere of illusions generated in the music-hall, England was suddenly compelled to face the fierce and terrible realities of life. Our country was called upon to fight or die; and it did not take her long to choose her course. From the outbreak of War it was clear that this was not a struggle of Armies against Armies, but of Peoples against Peoples, of Ideals against Ideals, of Organism against Organism. -

Efficiency and Long Service Decorations and Medals

364 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 14 JANUARY, 1958 MEDALS FOR GALLANTRY AND DISTINGUISHED Badge of Honour. CONDUCT. JUBILEE, CORONATION AND DURBAR MEDALS. Union of South Africa Queen's Medal for Bravery, in Gold. Queen Victoria's Jubilee Medal, 1887 (Gold, Distinguished Conduct Medal. || Silver and Bronze). Conspicuous Gallantry Medal.|| Queen Victoria's Police Jubilee Medal, 1887. George Medal. || Queen Victoria's Jubilee Medal, 1897 (Gold, Queen's Police Medal, for Gallantry. Silver and Bronze). Queen's Fire Service Medal, for Gallantry. Queen Victoria's Police Jubilee Medal, 1897. Edward Medal.|| Queen Victoria's Commemoration Medal, Royal West African Frontier Force Distin- 1900 (Ireland). guished Conduct Medal.|| King Edward VII's Coronation Medal, 1902. King's African Rifles Distinguished Conduct King 'Edward VII's Police Coronation Medal.l] Medal, 1902. Indian Distinguished Service Medal. || King Edward VII's Durbar Medal, 1903 Union of South Africa Queen's Medal for (Gold, Silver and Bronze). Bravery, in Silver. King Edward VII's Police Medal, 1903 Distinguished Service Medal. || (Scotland). Military Medal. |j King's Visit Commemoration Medal, 1903 Distinguished Flying Medal. || (Ireland). Air Force Medal. || King George V's Coronation Medal, 1911. Constabulary Medal (Ireland). King George V's Police Coronation Medal, Medal for Saving Life at Sea.*IJ 1911. Indian Order of Merit (CivU).ffl King's Visit Police Comimemoration Medal, Indian Police Medal for Gallantry. 1911 (Ireland). Ceylon Police Medal for Gallantry. King George V's Durbar Medal, 1911 Colonial Police Medal for Gallantry. (Gold,f Silver and Bronze). British Empire Medal.JU King George V's Silver Jubilee Medal, 1935. -

Fifth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm ORDERS, DECORATIONS

Together with case (this with foxing) and also letter date 5th June 1959 from Prime Minister's Offi ce at Whitehall to Miss J.M.Owens, The Coffer House, Fifth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm Newtown, Montgomeryshire, advising of the award. BEM: Supplement to LG 8/6/1950, p2803, to Miss Jessie May Owens, Member, Women's Voluntary Services, Newtown. ORDERS, DECORATIONS & MEDALS 1036 Imperial Service Medal, (GVR 1931-37). George William BRITISH SINGLES Penman. Impressed. No ribbon, very fi ne. $50 ISM: LG 15/12/1931, p8064, for Home Civil Service to George William Penman, Overseer, Post Offi ce, Manchester. With copy of Gazette pages. 1037 Imperial Service Medal, (GVIR Indiae Imp). Sidney Charles Pursey. Impressed. Good extremely fi ne. $50 ISM: Second Supplement to LG 22/6/1948, p3696 - for Home Civil Service, Admiralty, to Sidney Charles Pursey, storehouse assistant, H.M.Dockyard, Portsmouth. With copy of Gazette pages. 1038 Imperial Service Medal, (EIIR Dei Gratia). Edward John Clarence Wackley. Impressed. Extremely fi ne. $50 1034* ISM: Supplement to LG 30/5/1961, p3980 - for Home Civil Service, The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, (CB) (Civil), neck Admiralty, to Edward John Clarence Wackley, machinist, Devonport. badge in silver gilt, hallmarked. In case of issue, extremely With copy of Gazette pages. fi ne. $400 1035* Medal of the Order of the British Empire, (Civil), (GVIR), 1039* with ladies brooch ribbon. Miss Jessie M.Owens. Impressed. China War Medal 1842. James Grahme (sic) 26th Regiment Uncirculated. Foot. Impressed. Edge knocks, very fi ne. $250 $750 99 \ 1040* Indian Mutiny Medal 1857-58, - clasp - Central India, with brooch bar suspender and this engraved, 'Watch And/Be Sober'. -

WW2 Medal Criteria

WORLD WAR 2 GALLANTRY MEDALS George Cross Created 24 September 1940. Recognises acts of extreme bravery carried out by civilians and military personal when not under enemy fire. The act which earns the award must be witnessed by several individuals Named after King George VI, who personally designed many details on the medal inscription reads 'For Gallantry' Distinguished Service Order Awarded to officers who have performed meritorious or distinguished service inWar. The decoration, instituted by Queen Victoria in 1886, entitles recipients to add D.S.O. after their names. Military Cross The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces; and formerly also to officers of other Commonwealth countries. The MC is granted in recognition of "an act or acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy on land to all members, of any rank in Our Armed Forces” Distinguished Conduct Medal The oldest British award for gallantry and second only to the Victoria Cross, the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) was awarded to enlisted personnel, non- commissioned officers and warrant officers of any nation, in any branch of the service, for distinguished conduct in battle. Instigated by the British as a means of recognising acts of gallantry performed by 'other ranks' (i.e. non- commissioned officers) Military Medal The Military Medal (or MM) was a medal awarded for exceptional bravery. It was awarded to the Other Ranks (N.C.O.’s and Men) and was first instituted in 25 March 1916 during The First World War, to recognise bravery in battle. -

Honours and Awards in the Armed Forces

JSP 761 Honours and Awards in the Armed Forces Part 1: Directive JSP 761 Pt 1 (V4.0 Dec 14) 13D - i JSP 761 Pt 1 (V4.0 Dec 14) Foreword People lie at the heart of operational capability; attracting and retaining the right numbers of capable, motivated individuals to deliver Defence outputs is critical. This is dependent upon maintaining a credible and realistic offer that earns and retains the trust of people in Defence. In order to achieve this, all personnel must be confident that, not only will they be treated fairly, but also that their families will be treated properly and that Service veterans and their dependants will be respected and appropriately supported. JSP 761 is the authoritative guide for Honours and Awards in the Armed Services. It gives instructions on the award of Orders, Decorations and Medals and sets out the list of Honours and Awards that may be granted; detailing the nomination and recommendation procedures for each. It also provides information on the qualifying criteria for and permission to wear campaign medals, foreign medals and medals awarded by international organisations. It should be read in conjunction with Queen’s Regulations and DINs which further articulate detailed direction and specific criteria agreed by the Committee on the Grant of Honours, Decorations and Medals [Orders, Decorations and Medals (both gallantry and campaign)] or Foreign and Commonwealth Office [foreign medals and medals awarded by international organisations]. Lieutenant General Andrew Gregory Chief of Defence Personnel Defence Authority for People i JSP 761 Pt 1 (V4.0 Dec 14) Preface How to use this JSP 1. -

APPENDIX B, AMVHOF Bylaws (For Official Use Only)

APPENDIX B, AMVHOF Bylaws (For official Use Only) Medal of Honor The Army, Navy, and Air Force have different medals, but the same ribbon. Service cross medals. Awarded for "extraordinary heroism" Distinguished Service Cross (Army) Navy Cross Air Force Cross Coast Guard Cross Distinguished service medals Defense Distinguished Service Medal Arkansas Medal of Honor Homeland Security Distinguished Service Medal Distinguished Service Medal (Army) Navy Distinguished Service Medal Air Force Distinguished Service Medal Coast Guard Distinguished Service Medal Silver Star Awarded for "Gallantry in action" Superior service medals Defense Superior Service Medal Arkansas Military Medal Legion of Merit Distinguished Flying Cross B-4 Appendix B (2018 Version 2) APPENDIX B, AMVHOF Bylaws (For official Use Only) Medals for non-combat heroism Soldier’s Medal Arkansas Distinguished Service Medal Navy and Marine Corps Medal Airman’s Medal Coast Guard Medal Bronze Star Medal Awarded for heroism or meritorious service in a combat zone Purple Heart Awarded for wounds suffered in combat Meritorious service medals Defense Meritorious Service Medal Arkansas Exceptional Service Medal Meritorious Service Medal Air Medal Aerial Achievement Medal Commendation medals Joint Service Commendation Medal Arkansas Commendation Medal Army Commendation Medal Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal Air Force Commendation Medal Coast Guard Commendation Medal Achievement medals Joint Service Achievement Medal Army Achievement Medal Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal Air Force Achievement Medal Coast Guard Achievement Medal B-5 Appendix B (2018 Version 2) . -

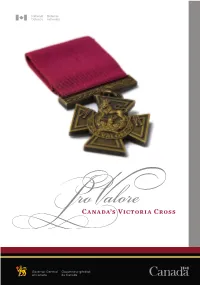

Canada's Victoria Cross

Canada’s Victoria Cross Governor General Gouverneur général of Canada du Canada Pro Valore: Canada’s Victoria Cross 1 For more information, contact: The Chancellery of Honours Office of the Secretary to the Governor General Rideau Hall 1 Sussex Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0A1 www.gg.ca 1-800-465-6890 Directorate of Honours and Recognition National Defence Headquarters 101 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0K2 www.forces.gc.ca 1-877-741-8332 Art Direction ADM(PA) DPAPS CS08-0032 Introduction At first glance, the Victoria Cross does not appear to be an impressive decoration. Uniformly dark brown in colour, matte in finish, with a plain crimson ribbon, it pales in comparison to more colourful honours or awards in the British or Canadian Honours Systems. Yet, to reach such a conclusion would be unfortunate. Part of the esteem—even reverence—with which the Victoria Cross is held is due to its simplicity and the idea that a supreme, often fatal, act of gallantry does not require a complicated or flamboyant insignia. A simple, strong and understated design pays greater tribute. More than 1 300 Victoria Crosses have been awarded to the sailors, soldiers and airmen of British Imperial and, later, Commonwealth nations, contributing significantly to the military heritage of these countries. In truth, the impact of the award has an even greater reach given that some of the recipients were sons of other nations who enlisted with a country in the British Empire or Commonwealth and performed an act of conspicuous Pro Valore: Canada’s Victoria Cross 5 bravery. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 28 May, 1943

2362 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 28 MAY, 1943 Acting Flight Lieutenant David John SHANNON, approaching the target his aircraft was raked by D.F.C. (Aus. 407729), Royal Australian Air Force, cannon fire from an enemy fighter. Wing Com- No. 617 Squadron. mander Crooks skilfully evaded the attacker but Pilot Officer Leslie Gordon KNIGHT (Aus-4Oi449), his aircraft had sustained much damage. Royal Australian -Air Force, No. 617 Squadron. Although one aileron and half the port tail plane had been shot away, while the hydraulic and Bar to Distinguished Flying Cross. electrical systems were rendered inoperative, Wing Acting Flight Lieutenant Robert Claude HAY, D.F.C. Commander Crooks flew the bomber back to this (Aus.407071), Royal Australian Air Force, No. 617 country. Unfortunately, it was impossible to Squadron. effect a safe landing but, when the crew were Acting Flight Lieutenant Robert Edward George forced to abandon aircraft, all descended safely. HUTCHISON, D.F.C. (120854), Royal Air Force In the face of heavy odds, Wing Commander Volunteer Reserve, No. 617 Squadron. Crooks set an example worthy of high praise. Acting Flight Lieutenant Jack Frederick LEGGO, D.F.C. (Aus.402367), Royal Australian Air Force, Bar to Distinguished Flying Cross. No. 617 Squadron. Acting Squadron Leader Keith Frederick THIELE, Flying Officer Daniel Revil WALKER, D.F.C. D.S.O., D.F.C. (N.Z.404966), Royal New Zealand (Can/J. 15336), Royal Canadian Air Force, No. 617 Air Force, No. 467 (R.A.A.F.) Squadron. Squadron. One night in May, 1943, this officer captained an aircraft detailed to attack Duisburg.