Ancient Lagash: a Workshop on Current Research and Future Trajectories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015–2016 Annual Report

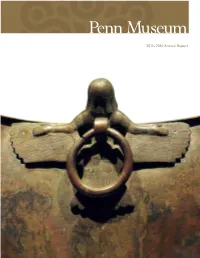

2015–2016 Annual Report 2015–2016 Annual Report 3 EXECUTIVE MESSAGE 4 THE NEW PENN MUSEUM 7 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE GEOGRAPHY 8 Teaching & Research: Penn Museum-Sponsored Field Projects 10 Excavations at Anubis-Mountain, South Abydos (Egypt) 12 Gordion Archaeological Project (Turkey) — Historical Landscape Preservation at Gordion — Gordion Cultural Heritage Education Project 16 The Penn Cultural Heritage Center — Conflict Culture Research Network (Global) — Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria & Iraq Project (Syria and Iraq) — Tihosuco Heritage Preservation & Community Development Project (Mexico) — Wayka Heritage Project (California, USA) 20 Pelekita Cave in Eastern Crete (Greece) 21 Late Pleistocene Pyrotechnology (France) 22 The Life & Times of Emma Allison (Canada) 23 On the Wampum Trail (North America) 24 Louis Shotridge & the Penn Museum (Alaska, USA) 25 Smith Creek Archaeological Project (Mississippi, USA) 26 Silver Reef Project (Utah, USA) 26 South Jersey (Vineland) Project (New Jersey, USA) 27 Collections: New Acquisitions 31 Collections: Outgoing Loans & Traveling Exhibitions 35 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE NUMBERS 40 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE MONTH 57 SUPPORTING THE MISSION 58 Leadership Supporters 62 Loren Eiseley Society 64 Expedition Circle 66 The Annual Fund 67 Sara Yorke Stevenson Legacy Circle 68 Corporate, Foundation, & Government Agency Supporters Objects on the cover, inside cover, and above were featured 71 THE GIFT OF TIME in the special exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas, from 72 Exhibition Advisors & Contributors February 13, 2016 through November 27, 2016. 74 Penn Museum Volunteers On the cover: Bronze cauldron with siren and demon 76 Board of Overseers attachments. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations 18516. -

The Foundation Figurines

Imagen aérea de uno de los Aerial view of one of the ziggu- zigurats de Babilonia. Imagen rats of Babylon. From Arqueo- de Arqueología de las ciudades logía de las ciudades perdidas, perdidas, núm. 4, 1992. Gentileza nº 4, 1992. Courtesy of Editorial de Editorial Salvat, S.L. Salvat, S. L. Tejidos mesopotámicos de 4.000 años de antigüedad: El caso de las figuritas de fundación Mesopotamian fabrics of 4000 years ago: the foundation figurines por / by Agnès Garcia-Ventura TODO EL MUNDO CONOCE EL CUENTO DE HANS CHRISTIAN ANDER- EVERYONE KNOWS HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEn’S TALE ABOUT THE SEN ACERCA DE LOS DOS SASTRES QUE PROMETEN AL EMPERADOR TWO TAILORS WHO PROMISE THE EMPEROR A NEW SUIT OF CLOTHES UN MÁGICO TRAJE NUEVO QUE SERÁ INVISIBLE PARA LOS IGNORAN- THAT ONLY THE WISEST AND CLEVEREST CAN SEE. WHEN THE EMPER- TES Y LOS INCOMPETENTES. CUANDO, POR FIN, EL EMPERADOR SE OR PARADES BEFORE HIS SUBJECTS IN HIS NEW CLOTHES, A CHILD PASEA ANTE SUS SÚBDITOS CON EL SUPUESTO TRAJE NUEVO, UN NIÑO CRIES OUT, “BUT HE ISn’T WEARING ANYTHING AT all!” GRITA: «¡PeRO SI NO LLEVA NINGÚN TRAJE!». A menudo, lo que aquí es simplemente una fábula sucede In the study of ancient textiles, I often think we act like the en realidad a quienes nos dedicamos al estudio de tejidos child in the fable, shouting out the obvious. But in this case antiguos. De algún modo, actuamos como el niño de la fá- it’s the other way round: “He is wearing something! Look at bula vociferando algo obvio, aunque en nuestro caso sería the textiles!” lo contrario que en el cuento de Andersen: «¡Pero si lleva To illustrate the point, in this article I will focus on two algo! ¡Mirad qué tejidos!». -

The Calendars of Ebla. Part III. Conclusion

Andrews Unir~ersitySeminary Studies, Summer 1981, Vol. 19, No. 2, 115-126 Copyright 1981 by Andrews University Press. THE CALENDARS OF EBLA PART 111: CONCLUSION WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University In my two preceding studies of the Old and New Calendars of Ebla (see AUSS 18 [1980]: 127-137, and 19 [1981]: 59-69), interpreta- tions for the meanings of 22 out of 24 of their month names have been suggested. From these studies, it is evident that the month names of the two calendars can be analyzed quite readily from the standpoint of comparative Semitic linguistics. In other words, the calendars are truly Semitic, not Sumerian. Sumerian logograms were used for the names of two months of the Old Calendar and three months of the New Calendar, but it is most likely that the scribes at Ebla read these logograms with a Semitic equivalent. In the cases of the three logograms in the New Calendar these equiva- lents are reasonably clear, but the meanings of the names of the seventh and eighth months in the Old Calendar remain obscure. Not only do these month names lend themselves to a ready analysis on the basis of comparative Semitic linguistics, but, as we have also seen, almost all of them can be analyzed satisfactorily just by comparing them with the vocabulary of biblical Hebrew. Given some simple and well-known phonetic shifts, Hebrew cognates can be suggested for some 20 out of 24 of the month names in these two calendars. Some of the etymologies I have suggested may, of course, be wrong; but even so, the rather full spectrum of Hebrew cognates available for comparison probably would not be diminished greatly. -

A Sculpted Dish from Tello Made of a Rare Stone (Louvre–AO 153)

A Sculpted Dish from Tello Made of a Rare Stone (Louvre–AO 153) FRANÇOIS DESSET, UMR 7041 / University of Teheran* GIANNI MARCHESI, University of Bologna MASSIMO VIDALE, University of Padua JOHANNES PIGNATTI, “La Sapienza” University of Rome Introduction Close formal and stylistic comparisons with other artifacts of the same period from Tello make it clear A fragment of a sculpted stone dish from Tello (an- that Waagenophyllum limestone, stemming probably cient Ĝirsu), which was found in the early excavations from some Iranian source, was imported to Ĝirsu directed by Ernest de Sarzec, has been as studied by to be locally carved in Sumerian style in the palace us in the frame of a wider research project on artifacts workshops. Mesopotamian objects made of this rare made of a peculiar dark grey limestone spotted with stone provide another element for reconstructing white-to-pink fossil corals of the genus Waagenophyl- the patterns of material exchange between southern lum. Recorded in an old inventory of the Louvre, Mesopotamia and the Iranian Plateau in the late 3rd the piece in question has quite surprisingly remained millennium BC. unpublished until now. The special points of interest to be addressed here are: the uncommon type of stone, which was pre- The Artifact sumably obtained from some place in Iran; the finely We owe the first description of this dish fragment carved lion image that decorates the vessel; and the (Figs. 1–3), which bears the museum number AO mysterious iconographic motif that is placed on the 153, to Léon Heuzey: lion’s shoulder. A partially preserved Sumerian inscrip- tion, most probably to be attributed to the famous Une disposition semblable, mais dans des pro- ruler Gudea of Lagash should also be noted.1 portions beaucoup plus petites, se voit au pour- tour d’un élégant plateau circulaire, dont il ne * This artifact was generously brought to our attention by reste aussi qu’un fragment. -

O L O G Y Ancient Society and Economy

oi.uchicago.edu O L O G Y Ancient Society and Economy I. J. Gelb This report gives the gist of a paper that was read in the "Special Session on Archaeology of Syria: 'The Origins of Cities of Mesopotamia in the Third Millennium B.C.' " In order to avoid further confusion in geographical terminology, two names were introduced in the paper: "Ebla" for northern Syria and "Lagash" for southern Mesopotamia or ancient Babylonia. The names of Ebla and Lagash were chosen to be used symbolically for Syria and Babylonia for obvious reasons, "Ebla" because it is the only site from which doc umentation is available, and "Lagash" because it contains the best documentation. For a person who, like myself, has worked for years on the socio-economic history of ancient Babylonia, working on Ebla has been like working in a different world. The vast majority of the sources pertaining to Lagash and its area concern agriculture, including not only plowed fields but also the adjoining pastures, orchards, and forests, pro cessing of agricultural products, manufacture of finished goods, and registration of the incoming and outgoing prod ucts in the chancellery and its affiliates. Contrasting with the Lagash sources, one finds almost no texts pertaining to agriculture at Ebla, as the overwhelming mass of the economic and administrative sources of Ebla deal with the production of sheep's wool (and much less of linen and goat's hair), manufacture of textiles, and the registration of finished products for internal consumption and export in the chancellery and its affiliates. Facing the archival treasures of Ebla, I felt somewhat like Francisco Pizarro when he entered an Inca storehouse in Cuzco and was overwhelmed by the mountain of wool blan kets piled up from floor to ceiling. -

The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict 9

CHAPTER I Introduction: Early Civilization and Political Organization in Babylonia' The earliest large urban agglomoration in Mesopotamia was the city known as Uruk in later texts. There, around 3000 B.C., certain distinctive features of historic Mesopotamian civilization emerged: the cylinder seal, a system of writing that soon became cuneiform, a repertoire of religious symbolism, and various artistic and architectural motifs and conven- tions.' Another feature of Mesopotamian civilization in the early historic periods, the con- stellation of more or less independent city-states resistant to the establishment of a strong central political force, was probably characteristic of this proto-historic period as well. Uruk, by virtue of its size, must have played a dominant role in southern Babylonia, and the city of Kish probably played a similar role in the north. From the period that archaeologists call Early Dynastic I1 (ED 11), beginning about 2700 B.c.,~the appearance of walls around Babylonian cities suggests that inter-city warfare had become institutionalized. The earliest royal inscriptions, which date to this period, belong to kings of Kish, a northern Babylonian city, but were found in the Diyala region, at Nippur, at Adab and at Girsu. Those at Adab and Girsu are from the later part of ED I1 and are in the name of Mesalim, king of Kish, accompanied by the names of the respective local ruler^.^ The king of Kish thus exercised hegemony far beyond the walls of his own city, and the memory of this particular king survived in native historical traditions for centuries: the Lagash-Umma border was represented in the inscriptions from Lagash as having been determined by the god Enlil, but actually drawn by Mesalim, king of Kish (IV.1). -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Personal Name: John R. Alden Address: 1215 Lutz Ave., Ann Arbor, MI 48103 Phone/e-mail: (734) 223-7668; [email protected] Education B.S. Cornell University, 1969 -- Chemical Engineering A.M. University of Pennsylvania, 1973 -- Anthropology Ph.D. University of Michigan, 1979 -- Anthropology Academic Employment 1979-80 Visiting Assistant Professor, Duke University Department of Anthropology teaching introductory level courses on archeology and human evolution and upper level undergraduate courses on regional analysis and the archeology of complex societies 1992-2013 Adjunct Associate Research Scientist, Univ. of MI Museum of Anthropology 2013-present Research Affiliate, Univ. of MI Museum of Anthropological Archaeology Grants and Fellowships 1976 NSF Dissertation Improvement Grant, #BNS-76-81955 1978 Dissertation Year Fellowship, University of Michigan 1991 National Geographic Society Research Grant, "Mapping Inka Installations in the Atacama," with Thomas F. Lynch, P. I. 2003 National Geographic Society Research Grant #7429-03, “Politics, Trade, and Regional Economy in the Bronze Age Central Zagros,” with Kamyar Abdi, P. I. 2008 White-Levy Program for Archaeological Publications Grant, “Excavations in the GHI Area of Tal-e Malyan, Fars Province, Iran.” 2009 White-Levy Program for Archaeological Publications Grant, 2nd year of funding Publications 1973 The Question of Trade in Proto-Elamite Iran. A.M. Thesis, Univ. of Pennsylvania Dept. of Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA. 1977 "Surface Survey at Quachilco." In R. D. Drennan, ed., The Palo Blanco Project: A Report on the 1975 and 1976 Seasons in the Tehuacán Valley, pp. 16-22. Univ. of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Ann Arbor, MI. 1978 "A Sasanian Kiln From Tal-i Malyan, Fars." Iran XVI: 127-133. -

Interdisciplinaria Archaeologica Natural Sciences in Archaeology

Volume IX ● Issue 1/2018 ● Online First INTERDISCIPLINARIA ARCHAEOLOGICA NATURAL SCIENCES IN ARCHAEOLOGY homepage: http://www.iansa.eu IX/1/2018 Book Reviews Ancient Iran & Its Neighbours: Local thirty-three international authors regarding earliest writing system in Iran” (p. 353, developments and long-range interactions all aspects of archaeological research and chap. 18) should be a really helpful study in the fourth millennium BC, 1th Edition, the history of the territory belonging to material for university students. Cameron A. Petrie, Oxbow Books 2013, ancient Iran during the fourth millennium But there is one contribution that ISBN 978-1-78297-227-3, 400 pages BC. Scholars, mostly from European, impressed me the most: Lloyd Weeks (hardcover). American, Iranian and other universities, (Department of Archeology, University of deal with fundamental topics, including the Nottingham, United Kingdom) has written environment, landscape, sites, technologies, a chapter with the title “Iranian metallurgy synthesis, etc. The publication by Oxbow of the fourth millennium BC in its wider Books (2013) was given the subtitle: “Local technological and cultural contexts” (p. developments and long-range interactions 277, chap. 15). In its introduction, this author in the fourth millennium BC” and edited shows the importance of the development by Cameron A. Petrie (Department of of the following metal metallurgy: copper, Archaeology and Anthropology at the lead, gold and silver. From a metallurgical University of Cambridge). The book came perspective this Iranian evidence is critical about under the patronage of The British for understanding and characterizing the Institute of Persian Studies, which is a development of early metallurgy. The self-governing charity bringing together most significant archaeological sites are distinguished scholars and others with an mentioned – Ghabristan, Tepe Hissar, interest in Iranian and Persian studies. -

Empire and History: Assyria, Persia, Rome

Department of the History of Art University of Pennsylvania Arth 301-302. Empire and History Assyria, Persia and Rome Spring 2003 Undergraduate Seminar Wednesdays 2-5 pm Course homepage: <http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~harmansa/Empire.html> Instructor: Prof. Holly Pittman ([email protected]; office: 898-3251; office hours: Thursdays 3:30-5 pm by appointment-sign-up at Art History office-) Teaching Assistant: Ömür Harmansah ([email protected]; office hours: Friday 10-12 by appointment) Collaborating: Xin Wu ([email protected]) Books on Reserve for general reference Larsen, Mogens Trolle (ed.);. Power and Propaganda: A Symposium on Ancient Empires. Copenhagen, 1979. [Museum Library desk DS62.2 .P68] Kuhrt, Amélie; The Ancient Near East: c. 3000-330 BC, 2 volumes. Routledge: London and New York, 1995. [Fine Arts Library Reserve DS62.23 .K87 1995] Roaf, Michael; Cultural atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East. Oxfordshire, 1996. [Museum Library Reserve DT60 .B34 2000] Henri Frankfort, The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient (Yale University Press Pelican History of Art.(with revisions by Michael Roaf and Donald Matthews), 1996. [Fine Arts Library Reserve N5345 .F7 1970] Torelli, Mario, Typology & structure of Roman historical reliefs. Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 1982. [Fine Arts Reserve NB133 .T57 1982] Weekly schedule and required readings (in progress) Week 1. January 15. First meeting: introduction. Week 2. January 22. Empires. Lecture and discussion on empires: development, types, and their various aspects. Introduction to the three empires of the course: Assyria, Persia and Rome Readings: [On reserve at Fine Arts library Reserve Desk, also available on line on Course Blackboard under Course Documents: You will have to 1 be signed up for the course to have access to the blackboard page for this course.] Sinopoli, Carla M.; "The archaeology of empires," Annual review of anthropology 23 (1994) 159-180. -

" King of Kish" in Pre-Sarogonic Sumer

"KING OF KISH" IN PRE-SAROGONIC SUMER* TOHRU MAEDA Waseda University 1 The title "king of Kish (lugal-kiski)," which was held by Sumerian rulers, seems to be regarded as holding hegemony over Sumer and Akkad. W. W. Hallo said, "There is, moreover, some evidence that at the very beginning of dynastic times, lower Mesopotamia did enjoy a measure of unity under the hegemony of Kish," and "long after Kish had ceased to be the seat of kingship, the title was employed to express hegemony over Sumer and Akked and ulti- mately came to signify or symbolize imperial, even universal, dominion."(1) I. J. Gelb held similar views.(2) The problem in question is divided into two points: 1) the hegemony of the city of Kish in early times, 2) the title "king of Kish" held by Sumerian rulers in later times. Even earlier, T. Jacobsen had largely expressed the same opinion, although his opinion differed in some detail from Hallo's.(3) Hallo described Kish's hegemony as the authority which maintained harmony between the cities of Sumer and Akkad in the First Early Dynastic period ("the Golden Age"). On the other hand, Jacobsen advocated that it was the kingship of Kish that brought about the breakdown of the older "primitive democracy" in the First Early Dynastic period and lead to the new pattern of rule, "primitive monarchy." Hallo seems to suggest that the Early Dynastic I period was not the period of a primitive community in which the "primitive democracy" was realized, but was the period of class society in which kingship or political power had already been formed. -

Statue of Gudea

An Artifact Speaks • Artifact Information Sheet Artifact Name: Statue of Gudea Time Period of the Original: ca. 2150–2125 BCE Culture/Religion Group: Neo-Sumerian Material of the Original: Diorite Reproduction? Yes Background Information: During the Neo-Sumerian period, rulers controlled large, independent city-states in southern Mesopotamia. Lagash was ruled by Gudea ca. 2150–2125 BCE. Unlike the kings of the previous Akkadian period, who represented themselves as strong, active, military leaders, Gudea emphasized his religious activities. He is known to have rebuilt at least fifteen temples, often using timbers and stones brought from faraway lands to replace the mud bricks that were the common building compo- nents. The greatest of the temples, known as Eninnu, was for Ningirsu, the national god. Gudea said he had been instructed to build the temple in a dream by the god himself. Gudea’s personal deity was Ningishzida, a fertility god called “Lord of the Tree of Life.” Found in excavations in the area of Lagash was a series of partial statues of Gudea. In some the king is standing; in others he is shown seated, as he is here. This statue was found at the site of Girsu, the ancient capital of Lagash, in two separate pieces at two different times. The head was found in 1877; the body was found in 1903. The two pieces, once it was found that they fit togeth- er, resulted in the only complete Gudea statue. The king is shown calm and smiling, resting on a low stool in the traditional pose of greeting, prayer, and attentiveness to divine command. -

Comptabilités, 8 | 2016 Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia During the Ur III Period 2

Comptabilités Revue d'histoire des comptabilités 8 | 2016 Archéologie de la comptabilité. Culture matérielle des pratiques comptables au Proche-Orient ancien Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III period Archéologie de la comptabilité. Culture matérielle des pratiques comptables au Proche-Orient ancien Archives et comptabilité dans le Sud mésopotamien pendant la période d’Ur III Archive und Rechnungswesen im Süden Mesopotamiens im Zeitalter von Ur III Archivos y contabilidad en el Periodo de Ur III (2110-2003 a.C.) Manuel Molina Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/comptabilites/1980 ISSN: 1775-3554 Publisher IRHiS-UMR 8529 Electronic reference Manuel Molina, « Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III period », Comptabilités [Online], 8 | 2016, Online since 20 June 2016, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/comptabilites/1980 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. Tous droits réservés Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III period 1 Archives and Bookkeeping in Southern Mesopotamia during the Ur III period* Archéologie de la comptabilité. Culture matérielle des pratiques comptables au Proche-Orient ancien Archives et comptabilité dans le Sud mésopotamien pendant la période d’Ur III Archive und Rechnungswesen im Süden Mesopotamiens im Zeitalter von Ur III Archivos y contabilidad en el Periodo de Ur III (2110-2003 a.C.) Manuel Molina 1 By the end of the 22nd century BC, king Ur-Namma inaugurated in Southern Mesopotamia the so-called Third Dynasty of Ur (2110-2003 BC). In this period, a large, well structured and organized state was built up, to such an extent that it has been considered by many a true empire.