Running Head: EXPERIENCES of MENTALLY RETARDED PARENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

At the Library: April 2018

April 2018 Vol. 49 No. 4 In the Community Poetry: Here, There & Everywhere with Kids Celebrate National Poetry Month at the Library by finding books from your favorite poets, attending readings in the branches, taking part Dia de los Niños/ in writing workshops and stopping by a new exhibit at the Main Library featuring Dia de Los Libros striking photos of local poets alongside their work. Celebrate the 19th year Enjoy new Poet Laureate of Día de los Niños/ Kim Shuck’s wit and wisdom In These Years After Frog is Kissed Día de los Libros festival as she celebrates the launch of with book giveaways, by Kim Shuck Endangered Species, Enduring entertainment, live music, a visit from the Values, an anthology of prose, Before love lost childhood’s tale bookmobile and fun poetry and artwork from And left the protection of first stories activities for children. Poet Laureate Kim Shuck Bay Area creators. Attend her Home water photo: Christopher Felver Día de los Niños workshops for children and Bromeliad cup is a Mexican holiday teens and hear her and other writers speak at a baseball recognizing the importance and influence of Moon’s cherished trickster was obscured themed poetry jam. children in society. Started in New Mexico in 1997, For more information, visit sfpl.org or view the Now we raise the event soon gained national recognition and Practices eyes in 1999, the Library began its own celebration calendar of events on pages 3-6. bringing together many agencies to honor Endangered Species, Enduring Values – April 8, 1 p.m., Sing the spring children, literacy, culture and books. -

Elmer Bernstein Elmer Bernstein

v7n2cov 3/13/02 3:03 PM Page c1 ORIGINAL MUSIC SOUNDTRACKS FOR MOTION PICTURES AND TV V OLUME 7, NUMBER 2 OSCARmania page 4 THE FILM SCORE HISTORY ISSUE RICHARD RODNEY BENNETT Composing with a touch of elegance MIKLMIKLÓSÓS RRÓZSAÓZSA Lust for Life in his own words DOWNBEAT DOUBLE John Q & Frailty PLUS The latest DVD and CD reviews HAPPY BIRTHDAY ELMER BERNSTEIN 50 years of film scores, 80 years of exuberance! 02> 7225274 93704 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada v7n2cov 3/13/02 3:03 PM Page c2 composers musicians record labels music publishers equipment manufacturers software manufacturers music editors music supervisors music clear- Score with ance arrangers soundtrack our readers. labels contractors scoring stages orchestrators copyists recording studios dubbing prep dubbing rescoring music prep scoring mixers Film & TV Music Series 2002 If you contribute in any way to the film music process, our four Film & TV Music Special Issues provide a unique marketing opportunity for your talent, product or service throughout the year. Film & TV Music Spring Edition: April 23, 2002 Film & TV Music Summer Edition: August 20, 2002 Space Deadline: April 5 | Materials Deadline: April 11 Space Deadline: August 1 | Materials Deadline: August 7 Film & TV Music Fall Edition: November 5, 2002 Space Deadline: October 18 | Materials Deadline: October 24 LA Judi Pulver (323) 525-2026, NY John Troyan (646) 654-5624, UK John Kania +(44-208) 694-0104 www.hollywoodreporter.com v7n02 issue 3/13/02 5:16 PM Page 1 CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2002 departments 2 Editorial The Caviar Goes to Elmer. 4News Williams Conducts Oscar, More Awards. -

The Impact of a Parent Involvement Program Designed to Support a First Grade Reading Intervention Program

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 356 450 CS 011 260 AUTHOR Rubert, Helene TITLE The Impact of a Parent Involvement Program Designed To Support a First Grade Reading Intervention Program. PUB DATE Feb 93 NOTE 241p.; Ed.D. Dissertation, National-Louis University. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Doctoral Dissertations (041) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Case Studies; Early Intervention; Grade 1; Literacy Education; Parent Child Relationship; *Parent Education; *Parent Participation; Primary Education; Reading Instruction; Reading Research; Reading Strategies IDENTIFIERS *Emergent Literacy; Illinois; Scaffolding ABSTRACT A study examined the impact of a parent involvement program for parents of children involved in a first-grade reading intervention program in Bakersville, a middle-class suburbnorth of Chicago, Illinois. Parents attended three workshops designedto complement their children's one-on-one tutorialprogram. Analysis focused on case studies of three families and the issuesaddressed concerned: how well parents learned the strategies presentedat the workshops, and did they use these ina responsive manner; how parents' beliefs about their children'sprogress and their own ability to support their children's zzading changedover time; and how home literacy resources and literacy-relatedevents changed over time. Data were coded and displayed in graphsand tables. Findings showed that while all parents learned the strategiespresented at the workshops, some had more success with the techniques thanothers. Parents whose initial theories more closely matched thosepresented at the workshops were able to modify their theoriesmore easily than those who held conflicting beliefs. Findings alsodemonstrated the importance of scaffolded instructionon two levels: between workshop leaders and parents as they learn new skills and betweenparents and their children as the parents support their childrenin new endeavors. -

Karaoke with a Message – September 29, 2018 a Project of Angel Nevarez & Valerie Tevere at Interference Archive (314 7Th St

Another Protest Song: karaoke with a message – September 29, 2018 a project of Angel Nevarez & Valerie Tevere at Interference Archive (314 7th St. Brooklyn, NY 11215) karaoke provided by All American Karaoke, songbook edited by Angel Nevarez & Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255 Logic/Alessia Cara/Khalid A 614 A Beautiful Life Ace -

Library 3398 Songs, 7.2 Days, 12.30 GB

Library 3398 songs, 7.2 days, 12.30 GB Song Name Artist Album _Secret Agent - Guster Keep It Together – Celtic Twilight Loreena McKennitt '85 Radio Special Thank You They Might Be Giants Then: The Earlier Years (CD 1) 'Ama'ama Israel "IZ" Kamakawiwo'ole Facing Future 'Round Springfield (Medley) The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… 'S Wonderful Ella Fitzgerald The Best Of the Song Books 'Til Him The Producers "Badge OF Honor"- Jerry Goldsmith Jerry Goldsmith L.A. Confidential "Chief Wiggum, P.I." Main Title The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Eye On Springfield" Theme The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… "Itchy & Scratchy" End Credits Theme The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… "Itchy & Scratchy" Main Title Theme The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… "Kamp Krusty" Theme Song The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Krusty The Clown" Main Title The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Oh, Streetcar!" (The Musical) The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… "Quimby" Campaign Commercial The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Scorpio" End Credits The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Simpsoncalifragilisticexpiala(Annoyed Grunt)Cio… The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Skinner & The Superintendent" Theme The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie Show" Theme The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "The Love-Matic Grampa" Main Title The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "The Simpsons" End Credits Theme The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "The Simpsons" End Credits Theme (Jazz Quartet -

Grammy Countdown U2, Nelly Furtado Interviews Kedar Massenburg on India.Arie Celine Dion "A New Day Has Come"

February 15, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 781 $6.00 GRAMMY COUNTDOWN U2, NELLY FURTADO INTERVIEWS KEDAR MASSENBURG ON INDIA.ARIE CELINE DION "A NEW DAY HAS COME" The premiere single from "A New Day Has Come," her first new album in two years and her first studio album since "Let's Talk About Love," which sold over 28 million copies worldwide. IMPACTING RADIO NOW 140 million albums sold worldwide 2,000,000+ cumulative radio plays and over 21 billion in combined audience 6X Grammy' winner Winner of an Academy Award for "My Heart Will Go On" Extensive TV and Press to support release: Week of Release Jprah-Entire program dedicated to Celine The View The Today Show CBS This Morning Regis & Kelly Upcoming Celine's CBS Network Special The Tonight Show Kicks off The Today Show Outdoor Concert Series Single produced by Walter Afanasieff and Aldo Nova, with remixes produced by Ric Wake, Humberto Gatica, and Christian B. Video directed by Dave Meyers will debut in early March. Album in stores Tuesday, March 26 www.epicrecords.com www.celinedion.com I fie, "Epic" and Reg. U.S. Pat. & Tm. Off. Marca Registrada./C 2002 Sony Music Entertainment (Canada) Inc. hyVaiee.sa Cartfoi Produccil6y Ro11Fair 1\lixeJyJo.serli Pui3 A'01c1 RDrecfioi: Ron Fair rkia3erneit: deter allot" for PM M #1 Phones WBLI 600 Spins before 2/18 Impact Early Adds: KITS -FM WXKS Y100 KRBV KHTS WWWQ WBLIKZQZ WAKS WNOU TRL WKZL BZ BUZZWORTHY -2( A&M Records Rolling Stone: "Artist To Watch" feature ras February 15, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 781 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher LENNY BEER THE DIVINE MISS POLLY Editor In Chief EpicRecords Group President Polly Anthony is the diva among divas, as Jen- TONI PROFERA Executive Editor nifer Lopez debuts atop the album chart this week. -

The Problem Body Projecting Disability on Film

The Problem Body The Problem Body Projecting Disability on Film - E d i te d B y - Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotic’ T h e O h i O S T a T e U n i v e r S i T y P r e ss / C O l U m b us Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The problem body : projecting disability on film / edited by Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotic´. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1124-3 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9222-8 (cd-rom) 1. People with disabilities in motion pictures. 2. Human body in motion pictures. 3. Sociology of disability. I. Chivers, Sally, 1972– II. Markotic´, Nicole. PN1995.9.H34P76 2010 791.43’6561—dc22 2009052781 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1124-3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9222-8) Cover art: Anna Stave and Steven C. Stewart in It is fine! EVERYTHING IS FINE!, a film written by Steven C. Stewart and directed by Crispin Hellion Glover and David Brothers, Copyright Volcanic Eruptions/CrispinGlover.com, 2007. Photo by David Brothers. An earlier version of Johnson Cheu’s essay, “Seeing Blindness On-Screen: The Blind, Female Gaze,” was previously published as “Seeing Blindness on Screen” in The Journal of Popular Culture 42.3 (Wiley-Blackwell). Used by permission of the publisher. Michael Davidson’s essay, “Phantom Limbs: Film Noir and the Disabled Body,” was previously published under the same title in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Volume 9, no. -

A Comparative Analysis of I Am Sam and Main Aisa Hi Hoon

Autism and Parenthood: A Comparative Analysis of I Am Sam and Main Aisa Hi Hoon Anisha Sen Abstract Disability has been variously portrayed in both Hollywood and Bollywood movies, with the ulterior motive of integrating the disabled into the social mainstream. For my study, I have chosen to focus on autism and how this particular disability is portrayed in two films- the American movie, I Am Sam (2001) and a Bollywood remake of it called Main Aisa Hi Hoon (2005). The same story is portrayed with the same theme, but, with different cultural contexts and in the hands of different directors, they develop interesting points of comparison. The idea of autism is integrated into a more generalized experience of parenthood, while addressing the doubts regarding heteronormative experiences of the disabled people. The optimistic views of the movie would present a positive scenario, but the way they achieve it is worth analyzing as certain pertinent social issues are also laid bare in the process. Keywords: autism, disability, normal, parent. Journal_ Volume 14, 2021_ Sen 47 I Am Sam, a 2001 movie released in America and its Bollywood remake Main Aisa Hi Hoon released in 2005, both revolve around an autistic parent and his struggle to bring up his child. The American movie stars Sean Penn in the lead role and is written and directed by Jessie Nelson. To prepare for his role, Sean Penn visited L.A. Goal, a centre in Los Angeles, for mentally handicapped people. Main Aisa Hi Hoon stars Ajay Devgan and is directed by Harry Baweja. What interested me about this topic was how the same story is taken with the same theme of autism and is depicted differently in the hands of different directors, with a different culture as the backdrop. -

Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM

Another Protest Song: Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM a project of Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere for SOMA Summer 2019 at La Morenita Canta Bar (Puente de la Morena 50, 11870 Ciudad de México, MX) karaoke provided by La Morenita Canta Bar songbook edited by Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255 -

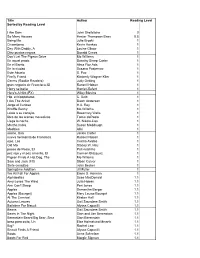

Reading Counts

Title Author Reading Level Sorted by Reading Level I Am Sam John Shefelbine 0 So Many Houses Hester Thompson Bass 0.5 Being Me Julie Broski 1 Crisantemo Kevin Henkes 1 Day With Daddy, A Louise Gikow 1 Diez puntos negros Donald Crews 1 Don't Let The Pigeon Drive Mo Willems 1 En aquel prado Dorothy Sharp Carter 1 En el Barrio Alma Flor Ada 1 En la ciudad Susana Pasternac 1 Este Abuelo S. Paz 1 Firefly Friend Kimberly Wagner Klier 1 Germs (Rookie Readers) Judy Oetting 1 gran negocio de Francisca, El Russell Hoban 1 Harry se baña Harriet Ziefert 1 Here's A Hint (FX) Wiley Blevins 1 Hip, el hipopótamo C. Dzib 1 I Am The Artist! Dawn Anderson 1 Jorge el Curioso H.A. Rey 1 Knuffle Bunny Mo Willems 1 Léale a su conejito Rosemary Wells 1 libro de las arenas movedizas Tomie dePaola 1 Llega la noche W. Nikola-Lisa 1 Martha habla Susan Meddaugh 1 Modales Aliki 1 noche, Una Jackie Carter 1 nueva hermanita de Francisca Russell Hoban 1 ojos, Los Cecilia Avalos 1 Old Mo Stacey W. Hsu 1 paseo de Rosie, El Pat Hutchins 1 pez rojo y el pez amarillo, El Carmen Blázquez 1 Pigeon Finds A Hot Dog, The Mo Willems 1 Sam and Jack (FX) Sloan Culver 1 Siete conejitos John Becker 1 Springtime Addition Jill Fuller 1 We All Fall For Apples Emmi S. Herman 1 Alphabatics Suse MacDonald 1.1 Amy Loves The Wind Julia Hoban 1.1 Ann Can't Sleep Peri Jones 1.1 Apples Samantha Berger 1.1 Apples (Bourget) Mary Louise Bourget 1.1 At The Carnival Kirsten Hall 1.1 Autumn Leaves Gail Saunders-Smith 1.1 Bathtime For Biscuit Alyssa Capucilli 1.1 Beans Gail Saunders-Smith 1.1 Bears In The Night Stan and Jan Berenstain 1.1 Berenstain Bears/Big Bear, Sma Stan Berenstain 1.1 beso para osito, Un Else Holmelund Minarik 1.1 Big? Rachel Lear 1.1 Biscuit Finds A Friend Alyssa Capucilli 1.1 Boots Anne Schreiber 1.1 Boots For Red Margie Sigman 1.1 Box, The Constance Andrea Keremes 1.1 Brian Wildsmith's ABC Brian Wildsmith 1.1 Brown Rabbit's Shape Book Alan Baker 1.1 Bubble Trouble Mary Packard 1.1 Bubble Trouble (Rookie Reader) Joy N. -

Ryan Alloway

Favorite Radio Format: I’m pretty all over the map Salem but these days probably a little more towards top 40. I ALUMNI Class of 2005 also tend to listen to a lot of 90s whenever I’m in the car with someone who has XM. P ROFILE Favorite Artist: Hard to pick one…The Beatles, but then again who doesn’t like them…these days it’s a lot of Fun, Imagine Dragons and Lady Gaga. Favorite Song: Oh even harder! Lately, I just can’t stop listening to “It’s Time” by Imagine Dragons, even though it’s well over a year old. “Eleanor Rigby” by the Beatles comes to mind (I love the orchestration- it’s mesmerizing), as well as “Viva La Vida” from Coldplay and “You and I” by Lady Gaga. Oh and pretty much the entire Jagged Little Pill album from Alanis Morissette. Favorite Movie: V for Vendetta, Little Miss Sunshine, I Am Sam, The Dark Knight and Mean Girls are clas - sics to me. Recently I really enjoyed Perks of Being a Wall*ower and The Conjuring. Ryan Alloway Favorite TV Show: I watch a ton of TV these days, with a public relations specialization. Outside of class, I admittedly, maybe a little too much. Recent TV shows was heavily involved in both TV (MSU Telecasters) and would be Homeland, American Horror Story, Game radio (WDBM-FM East Lansing, The Impact) at MSU. of Thrones, Revenge and Downton Abbey. Favorite That path eventually lead to a great internship oppor - shows of all time would probably be X-Files and Doug.