“The Girls We Left Behind”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Historical Society of Minnesota

The 34th “Red Bull” Infantry Division 1917-2010 Organization and World War One The 34th Infantry Division was created from National Guard troops of Minnesota, Iowa, the Dakotas and Nebraska in late summer 1917, four months after the US entered World War One. Training was conducted at Camp Cody, near Deming, New Mexico (pop. 3,000). Dusty wind squalls swirled daily through the area, giving the new division a nickname: the “Sandstorm Division.” As the men arrived at Camp Cody other enlistees from the Midwest and Southwest joined them. Many of the Guardsmen had been together a year earlier at Camp Llano Grande, near Mercedes, Texas, on the Mexican border. Training went well, and the officers and men waited anxiously throughout the long fall and winter of 1917-18 for orders to ship for France. Their anticipation turned to anger and frustration, however, when word was received that spring that the 34th had been chosen to become a replacement division. Companies, batteries and regiments, which had developed esprit de corps and cohesion, were broken up, and within two months nearly all personnel were reassigned to other commands in France. Reduced to a skeleton of cadre NCOs and officers, the 34th remained at Camp Cody just long enough for new draftees to refill its ranks. The reconstituted division then went to France, but by the time it arrived in October 1918, it was too late to see action. The war ended the following month. Between Wars After World War One, the 34th was reorganized with National Guardsmen from Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota. -

Gfk Italia CERTIFICAZIONI ALBUM Fisici E Digitali Relative Alla Settimana 47 Del 2019 LEGENDA New Award

GfK Italia CERTIFICAZIONI ALBUM fisici e digitali relative alla settimana 47 del 2019 LEGENDA New Award Settimana di Titolo Artista Etichetta Distributore Release Date Certificazione premiazione ZERONOVETOUR PRESENTE RENATO ZERO TATTICA RECORD SERVICE 2009/03/20 DIAMANTE 19/2010 TRACKS 2 VASCO ROSSI CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2009/11/27 DIAMANTE 40/2010 ARRIVEDERCI, MOSTRO! LIGABUE WARNER BROS WMI 2010/05/11 DIAMANTE 42/2010 VIVERE O NIENTE VASCO ROSSI CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2011/03/29 DIAMANTE 19/2011 VIVA I ROMANTICI MODA' ULTRASUONI ARTIST FIRST 2011/02/16 DIAMANTE 32/2011 ORA JOVANOTTI UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2011/01/24 DIAMANTE 46/2011 21 ADELE BB (XL REC.) SELF 2011/01/25 8 PLATINO 52/2013 L'AMORE È UNA COSA SEMPLICE TIZIANO FERRO CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2011/11/28 8 PLATINO 52/2013 TZN-THE BEST OF TIZIANO FERRO TIZIANO FERRO CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2014/11/25 8 PLATINO 15/2017 MONDOVISIONE LIGABUE ZOO APERTO WMI 2013/11/26 7 PLATINO 18/2015 LE MIGLIORI MINACELENTANO CLAN CELENTANO SRL - PDU MUSIC SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 2016/11/11 7 PLATINO 12/2018 INEDITO LAURA PAUSINI ATLANTIC WMI 2011/11/11 6 PLATINO 52/2013 BACKUP 1987-2012 IL BEST JOVANOTTI UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2012/11/27 6 PLATINO 18/2015 SONO INNOCENTE VASCO ROSSI CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2014/11/04 6 PLATINO 39/2015 CHRISTMAS MICHAEL BUBLE' WARNER BROS WMI 2011/10/25 6 PLATINO 51/2016 ÷ ED SHEERAN ATLANTIC WMI 2017/03/03 6 PLATINO 44/2019 CHOCABECK ZUCCHERO UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2010/10/28 5 PLATINO 52/2013 ALI E RADICI EROS RAMAZZOTTI RCA ITALIANA SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 2009/05/22 5 PLATINO 52/2013 NOI EROS RAMAZZOTTI UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2012/11/13 5 PLATINO 12/2015 LORENZO 2015 CC. -

World War II Research Subject Guide Louisiana State Archives

World War II Research Subject Guide Louisiana State Archives Introduction: This guide was made by archival staff at the Louisiana State Archives as an introduction to some of the materials we have on the Second World War for the state of Louisiana. Most of these collections pertain to Louisiana during the Second World War. The listings are arranged according to the Table of Contents listed below and then alphabetically within each section. For further information on this topic, or to view our collections, please visit the Louisiana State Archives Research Library or contact the Research Library staff at 225.922.1207 or via email at [email protected]. Table of Contents: Manuscripts Newspapers, Journals, and Magazines Military Records Photographs Microfilm Miscellaneous Manuscripts Bill Dodd Collection, 1944-1991, Photographs, newspaper clippings, campaign posters, and military service files of Bill Dodd. He served in public life from 1934 until 1991. Positions he held included teacher, legislator, state superintendent of public education, state auditor, Lieutenant Governor, and army officer. Dodd was born on November 25, 1909 in Liberty, Texas and died in Baton Rouge, November 16, 1991. Inventory is available. Collection No. N1992-032 Claire Chennault Collection, 1920-1958, Reports, family letters, newspaper clippings, photo negatives, magazines, photographs, military memorabilia, correspondence, and other materials pertaining to the life and career of Major General Claire Chennault. Inventory available. Collection No. N1991-005 Diane McMurray Collection, 1944-1945, A diary written by a clerk in the 602 Tank Destroyer Battalion during the period of March 29, 1944 to May 7, 1945 during World War II. -

Immortal Words: the Language and Style of the Contemporary Italian Undead-Romance Novel

Immortal Words: the Language and Style of the Contemporary Italian Undead-Romance Novel by Christina Vani A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Italian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Christina Vani 2018 Immortal Words: the Language and Style of the Contemporary Italian Undead-Romance Novel Christina Vani Doctor of Philosophy Department of Italian Studies University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This thesis explores the language and style of six “undead romances” by four contemporary Italian women authors. I begin by defining the undead romance, trace its roots across horror and romance genres, and examine the subgenres under the horror-romance umbrella. The Trilogia di Mirta-Luna by Chiara Palazzolo features a 19-year-old sentient zombie as the protagonist: upon waking from death, Mirta-Luna searches the Subasio region for her love… but also for human flesh. These novels present a unique interpretation of the contemporary “vampire romance” subgenre, as they employ a style influenced by Palazzolo’s American and British literary idols, including Cormac McCarthy’s dialogic style, but they also contain significant lexical traces of the Cannibali and their contemporaries. The final three works from the A cena col vampiro series are Moonlight rainbow by Violet Folgorata, Raining stars by Michaela Dooley, and Porcaccia, un vampiro! by Giusy De Nicolo. The first two are fan-fiction works inspired by Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight Saga, while the last is an original queer vampire romance. These novels exhibit linguistic and stylistic traits in stark contrast with the Trilogia’s, though Porcaccia has more in common with Mirta-Luna than first meets the eye. -

Poetry and the Visual in 1950S and 1960S Italian Experimental Writers

The Photographic Eye: Poetry and the Visual in 1950s and 1960s Italian Experimental Writers Elena Carletti Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. I acknowledge that this thesis has been read and proofread by Dr. Nina Seja. I acknowledge that parts of the analysis on Amelia Rosselli, contained in Chapter Four, have been used in the following publication: Carletti, Elena. “Photography and ‘Spazi metrici.’” In Deconstructing the Model in 20th and 20st-Century Italian Experimental Writings, edited by Beppe Cavatorta and Federica Santini, 82– 101. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019. Abstract This PhD thesis argues that, in the 1950s and 1960s, several Italian experimental writers developed photographic and cinematic modes of writing with the aim to innovate poetic form and content. By adopting an interdisciplinary framework, which intersects literary studies with visual and intermedial studies, this thesis analyses the works of Antonio Porta, Amelia Rosselli, and Edoardo Sanguineti. These authors were particularly sensitive to photographic and cinematic media, which inspired their poetics. Antonio Porta’s poetry, for instance, develops in dialogue with the photographic culture of the time, and makes references to the photographs of crime news. -

ORDER JO 7400.8T Air Traffic Organization Policy

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION ORDER JO 7400.8T Air Traffic Organization Policy February 7, 2011 SUBJ: Special Use Airspace 1. Purpose of This Order. This Order, published yearly, provides a listing of all regulatory and non-regulatory Special Use Airspace areas, as well as issued but not yet implemented amendments to those areas established by the Federal Aviation Administration. 2. Audience. Airspace and Aeronautical Operations, Air Traffic Controllers, and interested aviation parties. 3. Where Can I Find This Order. You can find this Order on the FAA employees’ Web site at https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices/, and the FAA Air Traffic Plans and Publications Web site at http://www.faa.gov/airports_airtraffic/air_traffic/publications/. 4. What This Order Cancels. JO FAA Order 7400.8S, Special Use Airspace, dated February 16, 2010 is canceled. 5. Effective Date. February 16, 2011. 6. Background. Actions establishing, amending, or revoking regulatory and non-regulatory designation of special use airspace areas, in the United States and its territories, are issued by the FAA and published throughout the year in the Federal Register or the National Flight Data Digest. These actions are generally effective on dates coinciding with the periodic issuance of Aeronautical Products navigational charts. For ease of reference, the FAA is providing this compilation of all regulatory and non-regulatory special use airspace areas in effect and pending as of February 1, 2011. Since revisions to this Order are not published between editions, the Order should be used for general reference only and not as a sole source of information where accurate positional data are required (e.g., video maps, letter of agreement, etc.). -

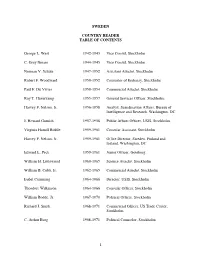

Table of Contents

SWEDEN COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George L. West 1942-1943 Vice Consul, Stockholm C. Gray Bream 1944-1945 Vice Consul, Stockholm Norman V. Schute 1947-1952 Assistant Attaché, Stockholm Robert F. Woodward 1950-1952 Counselor of Embassy, Stockholm Paul F. Du Vivier 1950-1954 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Roy T. Haverkamp 1955-1957 General Services Officer, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1956-1958 Analyst, Scandinavian Affairs, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC J. Howard Garnish 1957-1958 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Virginia Hamill Biddle 1959-1961 Consular Assistant, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1959-1961 Office Director, Sweden, Finland and Iceland, Washington, DC Edward L. Peck 1959-1961 Junior Officer, Goteborg William H. Littlewood 1960-1965 Science Attaché, Stockholm William B. Cobb, Jr. 1962-1965 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Isabel Cumming 1964-1966 Director, USIS, Stockholm Theodore Wilkinson 1964-1966 Consular Officer, Stockholm William Bodde, Jr. 1967-1970 Political Officer, Stockholm Richard J. Smith 1968-1971 Commercial Officer, US Trade Center, Stockholm C. Arthur Borg 1968-1971 Political Counselor, Stockholm 1 Haven N. Webb 1969-1971 Analyst, Western Europe, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC Patrick E. Nieburg 1969-1972 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Gerald Michael Bache 1969-1973 Economic Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1969-1974 Desk Officer, Scandinavian Countries, USIA, Washington, DC William Bodde, Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC Arthur Joseph Olsen 1971-1974 Political Counselor, Stockholm John P. Owens 1972-1974 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC James O’Brien Howard 1972-1977 Agricultural Officer, US Department of Agriculture, Stockholm John P. Owens 1974-1976 Political Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1974-1977 Press Attaché, USIS, Stockholm David S. -

Kazdan Pak Dissertation

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Italy's Primary Teachers: The Feminization of the Italian Teaching Profession, 1859-1911 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7fh45860 Author Pak, Julie Kazdan Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Italy’s Primary Teachers: The Feminization of the Italian Teaching Profession, 1859-1911 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Julie Kazdan Pak 2012 © Copyright by Julie Kazdan Pak 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Italy’s Primary Teachers: The Feminization of the Italian Teaching Profession, 1859-1911 by Julie Kazdan Pak Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Geoffrey Symcox, Chair This dissertation concerns the feminization of the Italian teaching profession between the introduction of pre-Unification schooling in 1859 and the nationalization of that system in 1911. By feminization, this dissertation refers both to the gradual assumption of the majority of elementary teaching positions by women and to a transformation in the nature of the position itself. Through an examination of educational periodicals, school records, government inquests, and accounts by teachers and pedagogical theorists, it argues that rather than the unintended consequence of economic constraints or shifting labor patterns, feminization was fundamentally connected to larger processes of centralization and modernization in the Italian school system. Following an introductory chapter outlining the major national, religious, and gender debates of ii the Unification era, the second chapter of the dissertation argues that the figure of the female elementary teacher became embroiled in the contest between local and national interests, furthering the drive toward centralization. -

Youth in Minneapolis, MN Minnesota Army National Guard, 1939-1941

Leadership and Lessons Learned: The Life and Career of Gen. John W. Vessey, Jr. Chapter 2 blonde girl that sat in the front row, and I sat in Narrator: Gen John W Vessey, Jr the back row. (chuckles) Interviewer: Thomas Saylor, Ph.D. TS: How did you get her to know who you Date of interview: 4 April 2012 were, General Vessey? Location: Vessey residence, North Oaks, MN JV: I don’t know the answer to that. I always Transcribed by: Linda Gerber, April 2012 thought she was out of my league (chuckles) and Edited for clarity by: Thomas Saylor, Ph.D., lo and behold, she passed me a note one day and May 2012 and January 2014 invited me to a Sadie Hawkins Day party, which (00:00) = elapsed time on digital recording was the 29 February 1940. TS: Today is Wednesday, 4 April 2012, and TS: Do you remember that particular date? this is the second interview with General John W. JV: I do indeed. Vessey, Jr. My name is Thomas Saylor. TS: Tell us some details. General Vessey, when we left off last time we JV: It was at the house of another classmate were talking about your high school experience who lived not too far from where I lived. Avis it Roosevelt High School in Minneapolis and lived on the west side of Lake Hiawatha and the I want to ask you about something that you Hiawatha Golf Course Park. We lived on the mentioned after finishing last time, which was east side of that about what you park area, on the called the most east side of Lake important thing Nokomis. -

Classifica Album Close

Radio UnYdea - Un Ydea di Radio - Classifica Album close SitiAllaRadio.it : Pubblicità a basso costo Advertising ● Home ● iRadio ● The Night ● Area Riservata ● Staff ● Contatti mercoledì 21 gennaio 2009 Password dimenticata? Nessun account? Registrati ● Dj Set http://www.radiounydea.it/index.php?option=com_newsfeeds&task=view&feedid=20&Itemid=105 (1 of 12)21/01/2009 19.16.37 Radio UnYdea - Un Ydea di Radio - Classifica Album ● Palinsesto ● Classifiche ❍ Classifica Singoli ❍ Classifica Album ❍ Dance Charts ❍ House Charts ❍ Hip Hop Charts ● Interviste ● Stagione Lirica 2007/2008 ● C'eravamo anche noi... ● News ● Oroscopo ● iPhone Club http://www.radiounydea.it/index.php?option=com_newsfeeds&task=view&feedid=20&Itemid=105 (2 of 12)21/01/2009 19.16.37 Radio UnYdea - Un Ydea di Radio - Classifica Album Thanks to: http://www.radiounydea.it/index.php?option=com_newsfeeds&task=view&feedid=20&Itemid=105 (3 of 12)21/01/2009 19.16.37 Radio UnYdea - Un Ydea di Radio - Classifica Album http://www.radiounydea.it/index.php?option=com_newsfeeds&task=view&feedid=20&Itemid=105 (4 of 12)21/01/2009 19.16.37 Radio UnYdea - Un Ydea di Radio - Classifica Album SitiAllaRadio.it : Pubblicità a basso costo http://www.radiounydea.it/index.php?option=com_newsfeeds&task=view&feedid=20&Itemid=105 (5 of 12)21/01/2009 19.16.37 Radio UnYdea - Un Ydea di Radio - Classifica Album Banca Monte Parma è una delle più antiche banche del mondo. Fu fondata nel 1488. Banca Monte Parma offre una gamma completa di prodotti e servizi ed opera in maniera capillare con oltre 60 sportelli su tutta la provincia di Parma e città limitrofe come Piacenza e Reggio Emilia. -

164Th Infantry News: May 1999

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons 164th Infantry Regiment Publications 5-1999 164th Infantry News: May 1999 164th Infantry Association Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation 164th Infantry Association, "164th Infantry News: May 1999" (1999). 164th Infantry Regiment Publications. 53. https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents/53 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in 164th Infantry Regiment Publications by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ....... =·~· THE 164 TH INFANTRY NEWS Vot39·No.X May X, 1999 164th J[nfantry Memorial Monument Walter Johnson departed this vale of tears 18 December proud of this. 1998 but he left us with the beautiful 1641h Infantry Memorial It was the last project of his career. Johnson was a long Monument, Veterans Cemetery, Mandan, North Dakota. time member of the American Institute of Architects, he was Johnson served in the 1641h from 1941 -1945 and returned to very proud of the initials AIA behind his name. In designing U.S. from the Philippines he completed his professional the 1641h monument Walter refused any Architectural fees schooling as an Architect at NDSU. Walt Johnson's creative offered to him. Thanks Walter Johnson. and design skills produced the 1641h monument, he was very Before Walter T. Johnson slipped away he was working in memory of deceased 164th Infantry men. on a project in which he really believed. -

Dr Gaetana Francesca RAPPAZZO

Dr Gaetana Francesca RAPPAZZO LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Scientific Journals 1. A. Ocherashvili, G.F. Rappazzo et al. (SELEX Coll.) Phys. Lett. B 628, 18-24 (2005) Ξ + + − Confirmation of the doubly charmed baryon cc (3520) via its decay to pD K 2. B. Adeva, G.F. Rappazzo et al. (DIRAC Coll.) Phys. Lett. B 619, 50-60 (2005) First measurement of the π+π− atom lifetime 3. D. Goldin, G.F. Rappazzo et al. (DIRAC Coll.) Int. J. Mod. Phys. A: HEP 20, 321-330 (2005) Measuring lifetime of the pionium atom with the DIRAC experiment 4. J. Engelfried, G.F. Rappazzo et al. (SELEX Coll.) Nucl. Phys. A 752, 121c-128c (2005) The Experimental Discovery of Double-Charm Baryons 5. P. Cooper, G.F. Rappazzo et al. (SELEX Coll.) Nucl. Phys. B - Proc. Suppl. 142, xv (2005) + 2 First Observation of a New Narrow DsJ Meson at 2632 MeV/c 6. P. Pogodin, G.F. Rappazzo et al. (SELEX Coll.) Phys. Rev. D 70, 112005(6) (2004) Polarization of Σ+ hyperons produced by 800 GeV/c protons on Cu and Be 7. A.V. Evdokimov, G.F. Rappazzo et al. (SELEX Coll.) Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 242001(5) (2004) + → + η 0 + Observation of a Narrow Charm-Strange Meson DsJ (2632) Ds and D K 8. B. Adeva, G.F. Rappazzo et al. (DIRAC Coll.) J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 30, 1929–1946 (2004) Detection of π+π− atoms with the DIRAC spectrometer at CERN 9. V.V. Molchanov, G.F. Rappazzo et al. (SELEX Coll.) Phys. Lett. B 590, 161-169 (2004) Upper limit on the decay Σ(1385)− → Σ− γ and cross section for γ Σ− → Λ π− 10.