Do Executive Compensation Contracts Maximize Firm Value? Evidence from a Quasi- Natural Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do Executive Compensation Contracts Maximize Firm Value? Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment

Do executive compensation contracts maximize firm value? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment Menachem (Meni) Abudy Bar-Ilan University, School of Business Administration, Ramat-Gan, Israel, 5290002 Dan Amiram Columbia University Graduate School of Business, 3022 Broadway, New York, NY 10027 Tel Aviv University, Coller School of Management, Ramat Aviv, Israel, 6997801 Oded Rozenbaum The George Washington University, 2201 G St. NW, Washington, DC 20052 Efrat Shust College of Management Academic Studies, School of Business, Rishon LeZion, Israel, 7549071 Current Draft: May 2017 First Draft: September 2016 For discussion purposes only. Please do not distribute. Please do not cite without the authors permission. Abstract: There is considerable debate on whether executive compensation contracts are a designed to maximize firm value or a result of rent extraction. The endogenous nature of executive pay contracts limits the ability of prior research to answer this question. In this study, we utilize the events surrounding a surprising and quick enactment of a new law that restricts executive pay to a binding upper limit in the insurance, investment and banking industries. This quasi-natural experiment enables clear identification. If compensation contracts are value maximizing, any outside restriction to the contract will diminish its optimality and hence should reduce firm value. In contrast to the predictions of the value maximization view of compensation contracts, we find significantly positive abnormal returns in these industries in multiple short term event windows around the passing of the law. We find that the effect is concentrated only for firms in which the restriction is binding. We find similar results using a regression discontinuity design, when we restrict our sample to firms with executive payouts that are just below and just above the law’s pay limit. -

Israel-Pakistan Relations Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies (JCSS)

P. R. Kumaraswamy Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies (JCSS) The purpose of the Jaffee Center is, first, to conduct basic research that meets the highest academic standards on matters related to Israel's national security as well as Middle East regional and international secu- rity affairs. The Center also aims to contribute to the public debate and governmental deliberation of issues that are - or should be - at the top of Israel's national security agenda. The Jaffee Center seeks to address the strategic community in Israel and abroad, Israeli policymakers and opinion-makers and the general public. The Center relates to the concept of strategy in its broadest meaning, namely the complex of processes involved in the identification, mobili- zation and application of resources in peace and war, in order to solidify and strengthen national and international security. To Jasjit Singh with affection and gratitude P. R. Kumaraswamy Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations Memorandum no. 55, March 2000 Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies 6 P. R. Kumaraswamy Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies Tel Aviv University Ramat Aviv, 69978 Tel Aviv, Israel Tel. 972 3 640-9926 Fax 972 3 642-2404 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.tau.ac.il/jcss/ ISBN: 965-459-041-7 © 2000 All rights reserved Graphic Design: Michal Semo Printed by: Kedem Ltd., Tel Aviv Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations 7 Contents Introduction .......................................................................................9 -

Excluded, for God's Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel

Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel המרכז הרפורמי לדת ומדינה -לוגו ללא מספר. Third Annual Report – December 2013 Israel Religious Action Center Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel Third Annual Report – December 2013 Written by: Attorney Ruth Carmi, Attorney Ricky Shapira-Rosenberg Consultation: Attorney Einat Hurwitz, Attorney Orly Erez-Lahovsky English translation: Shaul Vardi Cover photo: Tomer Appelbaum, Haaretz, September 29, 2010 – © Haaretz Newspaper Ltd. © 2014 Israel Religious Action Center, Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Israel Religious Action Center 13 King David St., P.O.B. 31936, Jerusalem 91319 Telephone: 02-6203323 | Fax: 03-6256260 www.irac.org | [email protected] Acknowledgement In loving memory of Dick England z"l, Sherry Levy-Reiner z"l, and Carole Chaiken z"l. May their memories be blessed. With special thanks to Loni Rush for her contribution to this report IRAC's work against gender segregation and the exclusion of women is made possible by the support of the following people and organizations: Kathryn Ames Foundation Claudia Bach Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation Bildstein Memorial Fund Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation Inc. Donald and Carole Chaiken Foundation Isabel Dunst Naomi and Nehemiah Cohen Foundation Eugene J. Eder Charitable Foundation John and Noeleen Cohen Richard and Lois England Family Jay and Shoshana Dweck Foundation Foundation Lewis Eigen and Ramona Arnett Edith Everett Finchley Reform Synagogue, London Jim and Sue Klau Gold Family Foundation FJC- A Foundation of Philanthropic Funds Vicki and John Goldwyn Mark and Peachy Levy Robert Goodman & Jayne Lipman Joseph and Harvey Meyerhoff Family Richard and Lois Gunther Family Foundation Charitable Funds Richard and Barbara Harrison Yocheved Mintz (Dr. -

Financing Land Grab

[Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 1 Financing Land Grab The Direct Involvement of Israeli Banks in the Israeli Settlement Enterprise February 2017 [Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 2 [Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 3 Financing Land Grab The Direct Involvement of Israeli Banks in the Israeli Settlement Enterprise February 2017 [Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 4 Who Profits from the Occupation is a research center dedicated to exposing the commercial involvement of Israeli and international companies in the continued Israeli control over Palestinian and Syrian land. Who Profits operates an online database, which includes information concerning companies that are commercially complicit in the occupation. In addition, the center publishes in-depth reports and flash reports about industries, projects and specific companies. Who Profits also serves as an information center for queries regarding corporate involvement in the occupation. In this capacity, Who Profits assists individuals and civil society organizations working to end the Israeli occupation and to promote international law, corporate social responsibility, social justice and labor rights. www.whoprofits.org | [email protected] [Released under the Official Information Act - July 2018] 5 Contents Executive Summary 7 Introduction 10 Israeli Construction on Occupied Land 14 Benefits for Homebuyers and Contractors in Settlements 16 Financing Construction on Occupied Land 20 The Settlement -

The Israeli Economy April 28, 2014 – May 2, 2014

THE TIKVAH FUND 165 E. 56th Street New York, New York 10022 UPDATED APRIL 23, 2014 The Israeli Economy April 28, 2014 – May 2, 2014 Roger Hertog, Dan Senor, and Ohad Reifen I. Description: Like much about the modern Jewish State, the Israeli economy is an improbable, fascinating, and precarious mix of great achievements and looming challenges. The legacy of its socialist past persists in many sectors of the economy and in the provision of many social services. And yet, Israel has emerged as one of the most dynamic, creative, entrepreneurial start-up economies in the world. Amid the recent economic downturn, the Israeli economy has fared well by comparison to most other advanced democracies. And yet, some of the pro-growth reforms of the recent past are under increasing political pressure. And for all the dynamism of its entrepreneurial class, the fastest growing sectors of Israeli society—the Haredim and the Arabs—are, comparatively, not well trained and not fully integrated into the work-force. For the Jewish State, economic success is a strategic—indeed, an existential—issue. Like all modern nations, Israel and its people yearn for a better life: more opportunity, more meaningful work, greater wealth for oneself and one’s family. And like all decent societies, Israel seeks an economy that serves and reflects the moral aspirations of its citizens, balancing a safety net for those in need and a culture of economic independence and initiative. But Israel is also different: economic stagnation would make it impossible to sustain the national power necessary to deter and confront its enemies, while exacerbating social tensions and fault lines between the various sectors of Israeli society. -

Research Department Bank of Israel

Bank of Israel Research Departmen t “Much Ado about Nothing”? The Effect of Print Media Tone on Stock Indices Mosi Rosenboim,a Yossi Saadon, b and Ben Z. Schreiber c Discussion Paper No. 2018.10 October 2018 ___________________ Bank of Israel; http://www.boi.org.il a Ben-Gurion University, Faculty of Management, [email protected] b Bank of Israel Research Department and Sapir College, [email protected] c (corresponding author) Bank of Israel Information and Statistics Department and Bar-Ilan University, [email protected] The authors thank Alon Eizenberg, Ron Kaniel, Doron Kliger, Ilan Kremer, Nathan Sussman, and the participants at the Bank of Israel Research Department seminar, the Bar-Ilan University AMCB forum, and the Ben-Gurion University research seminar, for their helpful comments and suggestions. We specially thank 'Ifat Media Research' company for providing us a unique database and the tone classifications. We also thank Yonatan Schreiber for technical assistance. Any views expressed in the Discussion Paper Series are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Israel חטיבת המחקר , בנק ישראל ת"ד 780 ירושלים 91007 Research Department, Bank of Israel. POB 780, 91007 Jerusalem, Israel Abstract We translate print media coverage into a gauge of human sentiment and the equivalent advertisement value, and find that the tone of media coverage substantially impacts stock markets. The tone has a positive effect on both overnight and daily stock returns but not on intraday returns, while conditional variance and daily price gaps are negatively influenced. This effect is significant on days of sharp price declines. -

To Download Israel at 100 (PDF)

The think tank for new Israeli politics Israel at 100 Noah Efron, Nazier Magally and Shaharit Fellows The Authors: Noah Efron is a Fellow at Shaharit. He teaches at Bar Ilan University, where he was the founding chairperson of the Program in Science, Technology & Society. He has served on the Tel Aviv-Jaffa City Council, on the Board of Directors and Scientific Committee of the Eretz Yisrael Museum, as the President of the Israeli Society for History & Philosphy of Science, and on the Advisory Board of the Columbia University Center for Science and Religion. Efron has been a member of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, the Dibner Institute for History of Science and Technology at MIT and a Fellow at Harvard University. He is the author of two books and many essays on the complicated intertwine of knowledge, religion and politics, and is the host of The Promised Podcast. Nazier Magally is a Fellow at Shaharit. He is a writer and journalist who lives and works in Nazareth. He served as editor-in-chief of Al-Ittihad, Israel's only Arabic-language daily. He presently is a member of the editorial staff of Eretz-Aheret, a columnist about matters of Israel for the London-based newspaper Asharq Alawsat, and the host of several news magazines on the Second Channel of Israeli television. Mr. Magally teaches at Bir Zeit University on the West Bank, and has taught at Ben Gurion University. He is a long-time activist in matters concerning the relations between Jews and Arabs in Israel and the region. -

Israel MARY LOITSKER

Opening the Budget to Citizens in Israel MARY LOITSKER. SUPERVISED BY DR. TEHILLA SHWARTZ ALTSHULER Demystifying Israel’s State Budget In 1985 Israel’s economy underwent a fundamental reform, following a decade of unrestrained inflation. In order to curb government spending, the Ministry of Finance introduced an extremely centralized budgeting regime and took almost full control over the allocation and management of the ministerial budgets. The economy soon stabilized, but this practice remained and became deeply ingrained into the organizational culture of the government.1 The Ministry thus gained a monopoly not only over the formulation of the state budget but also over budgeting knowledge. The subject of the budget evolved to be considered the exclusive professional domain of the Ministry’s economists. It was rarely subjected to more than a superficial discussion or scrutiny of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, or the broader public, who in turn had little understanding of or interest in the topic. The absence of easily accessible budget data further hindered the ability of the parliament and the public to monitor these processes. Civil society, academics, politicians, and judges have been criticizing for decades this disproportionate amount of control over the planning and management of the state budget concentrated in the hands of the Ministry of Finance.2 Civic-minded hackers were instrumental in providing a solution. After a lethal fire devastated the precious Carmel Forest in December 2010, an intense public debate followed about the underfunding of firefighting units. Adam Kariv, a techie activist who would later go on to found the Public Knowledge Workshop (PKW),3 went on to fact-check public accusations made in the media. -

Download PDF (391

JOURNAL OF PEACE AND WAR STUDIES 2nd Edition, October 2020 John and Mary Frances Patton Peace and War Center Norwich University, USA Journal of Peace and War Studies 2nd Edition, October 2020 CONTENTS ON THE PATH TO CONFLICT? SCRUTINIZING U.S.-CHINA RIVALRY Thucydides’s Trap, Clash of Civilizations, or Divided Peace? U.S.-China Competition from TPP to BRI to FOIP Min Ye China-Russia Military Cooperation and the Emergent U.S.-China Rivalry: Implications and Recommendations for U.S. National Security Lyle J. Goldstein and Vitaly Kozyrev U.S. and Chinese Strategies, International Law, and the South China Sea Krista E. Wiegand and Hayoun Jessie Ryou-Ellison Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Israel and U.S.-China Strategic Rivalry Zhiqun Zhu An Irreversible Pathway? Examining the Trump Administration’s Economic Competition with China Dawn C. Murphy STUDENT RESEARCH Why Wasn’t Good Enough Good Enough: “Just War” in Afghanistan John Paul Hickey Ukraine and Russia Conflict: A Proposal to Bring Stability John and Mary Frances Patton Peace and War Center Shayla Moya, Kathryn Preul, and Faith Privett Norwich University, USA The Journal of Peace and War Studies (JPWS) aims to promote and disseminate high quality research on peace and war throughout the international academic community. It also aims to provide policy makers in the United States and many other countries with in- depth analyses of contemporary issues and policy alternatives. JPWS encompasses a wide range of research topics covering peacekeeping/peacebuilding, interstate reconciliation, transitional justice, international security, human security, cyber security, weapons of mass destruction developments, terrorism, civil wars, religious/ethnic conflicts, and historical/ territorial disputes around the world. -

The Future of Israeli-Turkish Relations

The Future of Israeli- Turkish Relations Shira Efron C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2445 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018947061 ISBN: 978-1-9774-0086-4 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: cil86/stock.adobe.com Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since their inception, Israel-Turkey relations have been characterized by ups and downs; they have been particularly sensitive to developments related to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Throughout the countries’ seven-decade history of bilateral ties, Turkey has downgraded its diplomatic relations with Israel three times, most recently in 2011. -

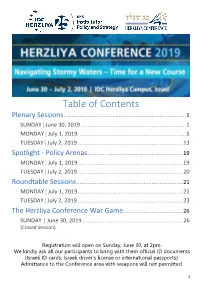

Conference Program

Table of Contents Plenary Sessions .............................................................................. 1 SUNDAY | June 30, 2019 ................................................................... 1 MONDAY | July 1, 2019 ..................................................................... 5 TUESDAY | July 2, 2019 ................................................................... 13 Spotlight - Policy Arenas ............................................................. 19 MONDAY | July 1, 2019 ................................................................... 19 TUESDAY | July 2, 2019 ................................................................... 20 Roundtable Sessions .................................................................... 21 MONDAY | July 1, 2019 ................................................................... 21 TUESDAY | July 2, 2019 ................................................................... 23 The Herzliya Conference War Game ...................................... 26 SUNDAY | June 30, 2019 ................................................................ 26 (Closed Session) Registration will open on Sunday, June 30, at 2pm. We kindly ask all our participants to bring with them official ID documents (Israeli ID cards, Israeli driver’s license or international passports). Admittance to the Conference area with weapons will not permitted. 1 Plenary Sessions SUNDAY | June 30, 2019 14:00 Welcome & Registration 15:00 Opening Ceremony Prof. Uriel Reichman, President & Founder, IDC Herzliya Prof. -

Quarterly Digest Israeli High Tech Market

Quarterly Digest Israeli High Tech Market (4th Quarter, 2013) 1 Contents Introduction 3 Report methodology 3 The trends 6 Public Market reopened for Israeli tech companies 6 IT and Mobile are the engines of the local industry 7 Enterprise software is an old-new superstar 8 Chemical industry and new materials 9 R&D centers of multinationals – from Facebook to unknown insurance company- everybody wants boots on the ground 10 Source of technology for Asian giants 10 Future trends – modest prediction attempt 11 Fundraising during Q4 12 IT 12 Biotech 15 Medical technologies 15 Engineering 18 Energy efficiency & clean-tech 19 Mobile 20 IPO Pipeline 24 M&A Deals during Q4 25 IT 26 Medical Technologies 26 Engineering 27 Mobile 29 Investment and Venture Capital in Israel 30 Technologies 37 IT 37 Medical Technologies 37 Mobile 38 Significant trade transaction and other related headlines 40 IT 40 Mobile 42 BioTech 42 Companies of special interest 43 2 Introduction Introduction This digest is an overview of the high tech industry, venture capital and adjusting areas news line of Israeli Hebrew written press and blogs. The main purpose of it is to present an unbiased picture of what is happening on one of the most vibrant technology markets. Usually, every technology start-up is trying to be secretive and not to reveal too much. Significant events in the company life (fundraising, M&A, significant trade transactions and contracts) allow the observers to get a picture of the market, to spot trends, to see where the investors (VC funds) are putting their money and what are strategic players after.