Internet Freedom in Azerbaijan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

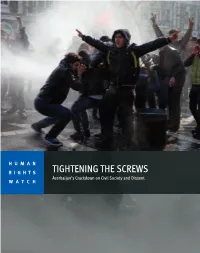

TIGHTENING the SCREWS Azerbaijan’S Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

1 2014 OSCE HUMAN DIMENSION IMPLEMENTATION MEETING September 22 - October 3, 2014 Written contribution of The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and The World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) Within the framework of their joint programme, The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders Under Working session 3: Fundamental freedoms I (continued), including freedom of peaceful assembly and association September 23, 2014 2 The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of their joint programme, the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, wish to draw the attention of the Organisation for the Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) on the ongoing threats and obstacles faced by human rights defenders in OSCE Participating States. In 2013 and 2014, human rights defenders in Eastern Europe and Central Asia continued to operate in a difficult, and sometimes hostile environment. The situation particularly deteriorated in Azerbaijan, Hungary, Kyrgyzstan, and the Russian Federation, where the civil society has continued to face acts of reprisals by the authorities and where domestic legal frameworks and practices governing the exercise of the right to freedoms of assembly and association were drastically restricted. In other countries, human rights defenders have continued to be subjected to arbitrary detention following blatantly unfair trials, in particular in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, or to lengthy pre-trial detention, -

IV. Imprisonment and Harassment of Human Rights Defenders and Lawyers

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

Internet Points of Control As Global Governance Laura Denardis INTERNET GOVERNANCE PAPERS PAPER NO

INTERNET GOVERNANCE PAPERS PAPER NO. 2 — AUGUST 2013 Internet Points of Control as Global Governance Laura DeNardis INTERNET GOVERNANCE PAPERS PAPER NO. 2 — AUGUST 2013 Internet Points of Control as Global Governance Laura DeNardis Copyright © 2013 by The Centre for International Governance Innovation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Centre for International Governance Innovation or its Operating Board of Directors or International Board of Governors. This work was carried out with the support of The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Waterloo, Ontario, Canada (www. cigionline.org). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — Non-commercial — No Derivatives License. To view this license, visit (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/). For re-use or distribution, please include this copyright notice. Cover and page design by Steve Cross. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT CIGI gratefully acknowledges the support of the Copyright Collective of Canada. CONTENTS About the Author 1 About Organized Chaos: Reimagining the Internet Project 2 Acronyms 2 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 3 Global Struggles Over Control of CIRS 5 Governance via Internet Technical Standards 8 Routing and Interconnection Governance 10 Emerging International Governance Themes 12 Works Cited 14 About CIGI 15 INTERNET GOVERNANCE PAPERS INTERNET POINTS OF CONTROL AS GLOBAL GOVERNANCE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Laura DeNardis Laura DeNardis, CIGI senior fellow, is an Internet governance scholar and professor in the School of Communication at American University in Washington, DC. Her books include The Global War for Internet Governance (forthcoming 2014), Opening Standards: The Global Politics of Interoperability (2011), Protocol Politics: The Globalization of Internet Governance (2009) and Information Technology in Theory (2007, with Pelin Aksoy). -

Azerbaijan: Downward Spiral: Continuing Crackdown on Freedoms in Azerbaijan

DOWNWARD SPIRAL: CONTINUING CRACKDOWN ON FREEDOMS IN AZERBAIJAN Amnesty International Publications First published in 2013 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2013 Index: EUR 55/010/2013 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. CONTENTS 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 2. Shrinking space for free media ................................................................................... 7 2.1 The continuing use of defamation suits to silence government critics ........................ 7 2.2 State control of broadcast media ........................................................................... 8 2.3 Harassment, intimidation and imprisonment of journalists ...................................... -

The Functioning of Democratic Institutions in Azerbaijan

http://assembly.coe.int Doc. 14403 25 September 2017 The functioning of democratic institutions in Azerbaijan Report1 Committee on the Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Member States of the Council of Europe (Monitoring Committee) Co-rapporteurs: Mr Stefan SCHENNACH, Austria, Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group, and Mr Cezar Florin PREDA, Romania, Group of the European People's Party Summary The Monitoring Committee has looked into the functioning of democratic institutions in Azerbaijan and assessed the state of implementation of the recommendations made by the Parliamentary Assembly in June 2015. It has focused in particular on questions relating to the application of the principle of separation of powers, the independence of the judiciary and the functioning of the criminal justice system. This report focuses on the human rights situation in the country, including the functioning of civil society and respect for political freedoms, the issue of the so-called “political prisoners”/”prisoners of conscience”, media freedom and freedom of expression. Taking into account developments and concerns, the committee calls for the full implementation of the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights in conformity with the resolutions of the Committee of Ministers and for the review of cases and release of those so-called “political prisoners” whose detention gives rise to justified doubts and legitimate concerns. It also makes a number of recommendations regarding checks and balances, to ensure full independence of the judiciary and to create conditions enabling media and civil society organisations to work. 1. Reference to committee: Resolution 1115 (1997). F - 67075 Strasbourg Cedex | [email protected] | Tel: +33 3 88 41 2000 | Fax: +33 3 88 41 2733 Doc. -

Azerbaijan0913 Forupload 1.Pdf

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

Azerbaijan 2015 Human Rights Report

AZERBAIJAN 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Azerbaijani constitution provides for a republic with a presidential form of government. Legislative authority is vested in the Milli Mejlis. The president dominated the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) canceled its observation of the November 1 legislative elections when the government refused to accept ODIHR’s recommended number of election monitors. Without ODIHR observation, it was impossible to assess fully the conduct of the Parliamentary election; independent local and international monitors alleged irregularities throughout the country. The 2013 presidential election did not meet a number of key OSCE standards for democratic elections. Separatists, with Armenia’s support, continued to control most of Nagorno-Karabakh and seven other Azerbaijani territories, and 622,892 persons reportedly remained internally displaced in December 2014 as a result of the unresolved conflict. There was an increase in violence along the Line of Contact and the Armenia-Azerbaijan border. Military actions throughout the year resulted in the highest number of deaths in one year since the signing of the 1994 ceasefire agreement, including six confirmed civilian casualties. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over Azerbaijani security forces. The most significant human rights problems during the year included: 1. Increased government restrictions on freedoms of expression, assembly, and association that were reflected in the intimidation, incarceration on questionable charges, and use of force against human rights defenders, activists, journalists, and some of their relatives. The operating space for activists and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) remained severely constrained. -

Introduction to Internet Governance

For easy reference: a list of frequently The history of this book is long, in Internet time. The used abbreviations and acronyms original text and the overall approach, including AN INTRODUCTION TO TO AN INTRODUCTION the five-basket methodology, were developed APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation in 1997 for a training course on information ccTLD country code Top-Level Domain AN INTRODUCTION TO and communications technology (ICT) policy CIDR Classless Inter-Domain Routing for government officials from Commonwealth DMCA Digital Millennium Copyright Act countries. In 2004, Diplo published a print version DNS Domain Name System of its Internet governance materials, in a booklet DRM Digital Rights Management INTERNET entitled Internet Governance – Issues, Actors and GAC Governmental Advisory Committee Divides. This booklet formed part of the Information gTLD generic Top-Level Domain INTERNET Society Library, a Diplo initiative driven by Stefano HTML HyperText Markup Language Baldi, Eduardo Gelbstein, and Jovan Kurbalija. IANA Internet Assigned Numbers Authority GOVERNANCE Special thanks are due to Eduardo Gelbstein, who ICANN Internet Corporation for Assigned made substantive contributions to the sections Names and Numbers GOVERNANCE dealing with cybersecurity, spam, and privacy, and ICC International Chamber of Commerce AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNET GOVERNANCE Jovan Kurbalija to Vladimir Radunovic, Ginger Paque, and Stephanie aICT Information and Communications Jovan Kurbalija Borg-Psaila who updated the course materials. Technology Comments and suggestions from other colleagues IDN Internationalized Domain Name are acknowledged in the text. Stefano Baldi, Eduardo IETF Internet Engineering Task Force An Introduction to Internet Governance provides a comprehensive overview Gelbstein, and Vladimir Radunovic all contributed IGF Internet Governance Forum of the main issues and actors in this field. -

Institute for Reporters' Freedom and Safety Azerbaijan's Free

Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety Azerbaijan’s Free Expression Crackdown Intensifies in Run-up to Election 2013 Biannual Report on Freedom of Expression in Azerbaijan This report is made possible thanks to support from International Media Support (IMS). The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the donor. IRFS is solely responsible for the analysis and recommendations contained herein. Cover photo: Obyektiv TV reporter, Rasim Aliyev was attacked by a police officer while filming a peaceful Baku protest in support of the Occupy Gezi protests in Turkey. June 03, Baku. © IRFS For more information visit: www.irfs.org or follow us on Twitter @IRFS_Azerbaijan 2 Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. Background 1.2. Objectives and focus 1.3. Methodology and structure 2. Recommendations 3. Chapter One: Violence, blackmail, and pressure against journalists 4. Chapter Two: Restrictions on privacy 5. Chapter Three: Legal repression of freedom of expression 6. Chapter Four: Detention of journalists, bloggers, and human rights defenders 7. Chapter Five: State control over the media 8. Chapter Six: Freedom of expression online 9. Conclusion 3 Introduction 1.1. Background This report is a publication of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), an independent, non-profit organization dedicated to promoting freedom of expression in Azerbaijan. IRFS was founded on World Press Freedom Day in 2006 by two Azerbaijani journalists in response to growing restrictions by the government on freedom of expression and media freedom. The organization’s reporting has been instrumental in bringing freedom of expression issues in Azerbaijan to the attention of relevant organizations and officials in the United States and Europe. -

The State of Broadband 2020: Tackling Digital Inequalities a Decade for Action

The State of Broadband: Tackling digital inequalities A decade for action September 2020 The State of Broadband 2020: Tackling digital inequalities A decade for action September 2020 © International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO license (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https:// creativecommons .org/ licenses/ by -nc -sa/ 3 .0/ igo). Under the terms of this license, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that ITU or UNESCO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The unauthorized use of the ITU or UNESCO names or logos is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons license. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) or the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Neither ITU nor UNESCO are responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the license shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization (http:// www .wipo .int/ amc/ en/ mediation/ rules). Suggested citation. State of Broadband Report 2020: Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2020. -

Azerbaijan: the Repression Games

AZERBAIJAN: THE REPRESSION GAMES THE VOICES YOU WON’T HEAR AT THE FIRST EUROPEAN GAMES 1 The first ever European Games are due to take place in (Above) Flame Towers in downtown Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, on 12-28 June 2015. This Baku © Amnesty International multi-sport event will involve around 6,000 athletes and features a new state-of-the-art stadium costing some US$640 million. The games will give a huge boost to the government’s campaign to portray Azerbaijan as a progressive and politically stable rising economic Key Country Facts power. According to the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, the hosting of the European Games ‘will enable Azerbaijan to assert itself again Head of State throughout Europe as a strong, growing and a modern state.’2 President Ilham Aliyev But behind the image trumpeted by the government of a forward-looking, Head of Government modern nation is a state where criticism of the authorities is routinely Artur Rasizadze and increasingly met with repression. Journalists, political activists and human rights defenders who dare to challenge the government face Population trumped up charges, unfair trials and lengthy prison sentences. 9,583,200 In recent years, the Azerbaijani authorities have mounted an Area unprecedented clampdown on independent voices within the country. 86,600 km2 They have done so quietly and incrementally with the result that their actions have largely escaped consequences. The effects, however, are unmistakable. When Amnesty International visited the country in March 2015, there was almost no evidence of independent civil society activities and dissenting voices have been effectively muzzled.