'From Pioneers to Parity? 100 Years of Suffrage'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harriet Harman QC MP

Harriet Harman QC MP Member of Parliament for Camberwell & Peckham House of Commons London SW1A 0AA 0207 219 4218 [email protected] www.harrietharman.org @HarrietHarman @UKLabour 1 For further information about my work in the constituency please see my website www.harrietharman.org Introduction For the Labour Party in Camberwell and Peckham, the next 12 months will be very different from the last. 2016 has been busy with elections. We had the Mayoral election, then the EU Referendum and then the Labour Leadership election. Next year we will be having no elections and that will give us the opportunity to campaign in every ward to build the support we need to get our councillors re-elected in 2018. It is always important to have a Labour Councillor on your side, but never more so than when there is a Tory government. And with the leadership election behind us it will be the chance for all members, including the over 2,000 who have joined us since 2015, to be out campaigning together. People locally will judge us not just by the discussions we have in our ward and in our GC but by our commitment to be out there campaigning on their doorstep, showing our solidarity with them as they face difficult times. And there is every possibility that, with the Government mired in difficulties over Brexit and with our low standing in the opinion polls, The Prime Minister might seek the opportunity of an early General Election. In the meantime the reality of a Tory government continues to press down on people. -

Making a Hasty Brexit? Ministerial Turnover and Its Implications

Making a Hasty Brexit? Ministerial Turnover and Its Implications Jessica R. Adolino, Ph. D. Professor of Political Science James Madison University Draft prepared for presentation at the European Studies Association Annual Meeting May 9-12, 2019, Denver, Colorado Please do not cite or distribute without author’s permission. By almost any measure, since the immediate aftermath of the June 16, 2016 Brexit referendum, the British government has been in a state of chaos. The turmoil began with then- Prime Minister David Cameron’s resignation on June 17 and succession by Theresa May within days of the vote. Subsequently, May’s decision to call a snap election in 2017 and the resulting loss of the Conservatives’ parliamentary majority cast doubt on her leadership and further stirred up dissension in her party’s ranks. Perhaps more telling, and the subject of this paper, is the unprecedented number of ministers1—from both senior and junior ranks—that quit the May government over Brexit-related policy disagreements2. Between June 12, 2017 and April 3, 2019, the government witnessed 45 resignations, with high-profile secretaries of state and departmental ministers stepping down to return to the backbenches. Of these, 34 members of her government, including 9 serving in the Cabinet, departed over issues with some aspect of Brexit, ranging from dissatisfaction with the Prime Minister’s Withdrawal Agreement, to disagreements about the proper role of Parliament, to questions about the legitimacy of the entire Brexit process. All told, Theresa May lost more ministers, and at a more rapid pace, than any other prime minister in modern times. -

Caroline Flint – How to Get the Drugs out of Crime

p01 cover.qxd 29/10/04 8:39 pm Page 1 From FDAP in association with WIRED 1 November 2004 Caroline Flint – how to get the drugs out of crime FDAP – new code of practice Your NEW fortnightly magazine | jobs | news | views Ads.qxd 29/10/04 7:32 pm Page 2 Client’s view (using drawpad) of screen in mid-session Assessor choosing actions to place on caller’s screen Launching this month From WIRED In association with FDAP and Distance Therapy Ltd VIRTUAL OUTREACH A uniquely secure online tool to bring together substance misuse professionals and their clients. Virtual Outreach has internet-based counselling, assessment, and groupwork rooms, with video and voice links, chat and whiteboard that give strict confidentiality and anonymity to your client. Use Virtual Outreach for: Assessment and referral Counselling (individual and group) Peer support Aftercare Virtual Outreach is based on the online therapy tools of DistanceTherapy.com, originally designed to help recovering gambling addicts. It has been specially developed to relate to substance misuse. To see demos and try out Distance Therapy, visit www.distancetherapy.com For further information, please contact: Professor David Clark [email protected] 07967-006569 p03 editor/contents.qxd 29/10/04 8:48 pm Page 3 Published by 1 November 2004 On behalf of FEDERATION OF DRUG AND ALCOHOL PROFESSIONALS Editor’s letter Welcome to our very first issue of Drink and work situations. But we’re not all about the official Drugs News! side of work. Natalie’s story (page 6) and Dave’s The 21st Century approach to tackling substance misuse Brought to you by the Federation of Drug and ‘day in the life’ (page 12) illustrate what we’re all Alcohol Professionals and Wired, the magazine will about: demonstrating that treatment and support give you a round-up of what’s going on, who’s services can, and most definitely do, make a real saying what, and the latest issues for debate, and lasting difference to people’s lives. -

Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard

This is a repository copy of Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82697/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Heppell, T and Bennister, M (2015) Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. Government and Opposition, FirstV. 1 - 26. ISSN 1477-7053 https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.31 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard Abstract This article examines the interaction between the respective party structures of the Australian Labor Party and the British Labour Party as a means of assessing the strategic options facing aspiring challengers for the party leadership. -

Shadow Cabinet Meetings with Proprietors, Editors and Senior Media Executives

Shadow Cabinet Meetings 1 June 2015 – 31 May 2016 Shadow cabinet meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives. Andy Burnham MP Shadow Secretary of State’s meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives Date Name Location Purpose Nature of relationship* 26/06/2015 Alison Phillips, Editor, Roast, The General Professional Sunday People Floral Hall, discussion London, SE1 Peter Willis, Editor, 1TL Daily Mirror 15/07/2015 Lloyd Embley, Editor in J Sheekey General Professional Chief, Trinity Mirror Restaurant, discussion 28-32 Saint Peter Willis, Editor, Martin's Daily Mirror Court, London WC2N 4AL 16/07/2015 Kath Viner, Editor in King’s Place Guardian daily Professional Chief, Guardian conference 90 York Way meeting London N1 2AP 22/07/2015 Evgeny Lebedev, Private General Professional proprieter, address discussion Independent/Evening Standard 04/08/2015 Lloyd Embley, Editor in Grosvenor General Professional Chief, Trinity Mirror Hotel, 101 discussion Buckingham Palace Road, London SW1W 0SJ 16/05/2016 Eamonn O’Neal, Manchester General Professional Managing Editor, Evening Manchester Evening News, discussion News Mitchell Henry House, Hollinwood Avenue, Chadderton, Oldham OL9 8EF Other interaction between Shadow Secretary of State and proprietors, editors and senior media executives Date Name Location Purpose Nature of relationship* No such meetings Angela Eagle MP Shadow Secretary of State’s meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives Date Name Location Purpose Nature of relationship* No -

Labour's Last Fling on Constitutional Reform

| THE CONSTITUTION UNIT NEWSLETTER | ISSUE 43 | SEPTEMBER 2009 | MONITOR LABOUR’S LAST FLING ON CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM IN THIS ISSUE Gordon Brown’s bold plans for constitutional constitutional settlement …We will work with the reform continue to be dogged by bad luck and bad British people to deliver a radical programme of PARLIAMENT 2 - 3 judgement. The bad luck came in May, when the democratic and constitutional reform”. MPs’ expenses scandal engulfed Parliament and government and dominated the headlines for a Such rhetoric also defies political reality. There is EXECUTIVE 3 month. The bad judgement came in over-reacting a strict limit on what the government can deliver to the scandal, promising wide ranging reforms before the next election. The 2009-10 legislative which have nothing to do with the original mischief, session will be at most six months long. There PARTIES AND ELECTIONS 3-4 and which have limited hope of being delivered in is a risk that even the modest proposals in the the remainder of this Parliament. Constitutional Reform and Governance Bill will not pass. It was not introduced until 20 July, DEVOLUTION 4-5 The MPs’ expenses scandal broke on 8 May. As the day before the House rose for the summer the Daily Telegraph published fresh disclosures recess. After a year’s delay, the only significant day after day for the next 25 days public anger additions are Part 3 of the bill, with the next small HUMAN RIGHTS 5 mounted. It was not enough that the whole steps on Lords reform (see page 2); and Part 7, to issue of MPs’ allowances was already being strengthen the governance of the National Audit investigated by the Committee on Standards in Office. -

Co-Operative Party Annual Conference 2015

co-operative party annual conference 2015 19th-20th September London Holiday Inn Regent’s Park Register online at party.coop/conference2015 2 Contents Leadership Candidates Deputy Leadership Candidates Andy Burnham 4 Ben Bradshaw 12 Yvette Cooper 6 Stella Creasy 14 Jeremy Corbyn 8 Angela Eagle 16 Liz Kendall 10 Caroline Flint 18 Tom Watson 20 3 Andy Burnham andy4leader andy4labour.co.uk The roots of the Labour movement are deep in the Co-operative Party. So are mine. I joined the Co-op Party when I saw the benefits that mutual support and collectivism could bring in the modern world. I was working with a football task force set up by the Labour Government to stop unscrupulous directors from asset-stripping clubs and taking them away from their communities and fans. Northampton Town found a new way of owning a club through a supporters’ trust, where fans ran the club through a democratic forum. It was obvious that this new mutualism was the way forward. On the recommendation of the Football Task Force, working with former Culture Secretary Chris Smith, we set up Supporters Direct to promote fan ownership of clubs. The idea blossomed. The number of supporters’ trusts exploded. But for me, the importance of that was not just that many football clubs were saved. It was that the Co-operative ideal, the belief in mutualism, was brought to a new, younger generation of people, who had never heard of co-operatives before. That is the way I want a Labour Party I lead and the Co-operative Party to work together. -

Key Economic Announcement at Conservative Conference Labour Announce Shadow Cabinet Resh

WEEK IN WESTMINSTER Week ending Friday 7 October departure of John Denham MP from the position of “Credit easing” key economic Shadow Business Secretary, replaced by Chuka announcement at Umunna MP, previously Shadow Business Minister. Denham will become Ed Miliband’s Parliamentary Conservative conference Private Secretary. Rachel Reaves MP replaces Angela Eagle MP as Shadow Chief Secretary to the Prime Minister, and Leader of the Conservative Party, Treasury. Hilary Benn MP moves from Shadow David Cameron, has delivered his keynote speech to Commons Leader to Shadow Secretary of State for the Conservative Party conference in Manchester, Communities and Local Government, replacing where he warned that the threat of global recession Caroline Flint who moves to replace Meg Hiller MP as was as serious as it was in 2008, and urged the “spirit Shadow Secretary of State for Energy and Climate of Britain” to help the country through this difficult Change. Andy Burnham MP moves from Shadow economic time. Mr. Cameron’s speech was delivered Education Secretary to Shadow Health Secretary, on the day that the Office of National Statistics halved replaced in the education brief by Stephen Twigg MP. its economic growth estimate for the UK for the Maria Eagle MP remains as Shadow Transport second quarter of 2011, down to just 0.1%. However Secretary. (Source: Labour) Mr. Cameron rejected Labour calls for a slowdown in http://www.labour.org.uk/labours-shadow-cabinet Chancellor Osborne’s deficit reduction plan, stating “Our plan is right and our plan will work”. There were few significant policy announcements in Mr. Cameron’s speech; however in Chancellor George Osborne’s earlier speech to conference, he announced that government would look at the options to get credit flowing to small firms through “credit easing”. -

Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament

Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Annual Report 2016–2017 Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Annual Report 2016–2017 Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Presented to Parliament pursuant to sections 2 and 3 of the Justice and Security Act 2013 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 20 December 2017 HC 655 © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at isc.independent.gov.uk Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us via our webform at isc.independent.gov.uk/contact ISBN 978-1-5286-0168-9 CCS1217631642 12/17 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office THE INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE OF PARLIAMENT This Report reflects the work of the previous Committee,1 which sat from September 2015 to May 2017: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP (Chair) The Rt. Hon. Richard Benyon MP The Most Hon. the Marquess of Lothian QC PC (from 21 October 2016) The Rt. Hon. Sir Alan Duncan KCMG MP The Rt. Hon. Fiona Mactaggart MP (until 17 July 2016) The Rt. Hon. -

Ejecting the Party Leader: Party Structures and Cultures: the Removal of Kevin Rudd and Non Removal of Gordon Brown

Ejecting the Party Leader: Party Structures and Cultures: The Removal of Kevin Rudd and Non Removal of Gordon Brown Dr Mark Bennister, Canterbury Christ Church University [email protected] Dr Tim Heppell, Leeds University PSA CONFERENCE CARDIFF UNIVERSITY 25 MARCH 2013 DRAFT ONLY – CONTACT AUTHORS FOR PERMISSION TO CITE Abstract This article examines the interaction between the respective party structures of the Australian Labor Party and the British Labour Party as a means of assessing the strategic options facing aspiring challengers for the party leadership. Noting the relative neglect within the scholarly literature on examining forced exits that occur; and attempted forced exits that do not occur, this article takes as its case study the successful forced exit of Kevin Rudd, and the failure to remove Gordon Brown. In doing so the article challenges the prevailing assumption that the likely success of leadership evictions are solely determined by the leadership procedures that parties adopt. Noting the significance of circumstances and party cultures, the article advances two scenarios through which eviction attempts can be understood: first, forced exits triggered through the activation of formal procedures (Rudd); second, attempts to force an exit by informal pressures outside of the formal procedures which are overcome by the incumbent (Brown). Keywords Prime Ministers; Party Leadership; Leadership Elections; Party Organisation; Kevin Rudd; Gordon Brown 1 Introduction In an age of valance, rather than positional politics, party identification and competition is increasingly shaped through electoral judgements about the competence and charisma of party leaders (Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley, 2004; Bean and Mughan, 1989; Clarke and Stewart, 1995; King, 2002; Aarts and Blais, 2009). -

Priorities of the European Union: Evidence from the Ambassador of the Czech Republic and the Minister for Europe

HOUSE OF LORDS European Union Committee 8th Report of Session 2008–09 Priorities of the European Union: evidence from the Ambassador of the Czech Republic and the Minister for Europe Report Ordered to be printed 21 April 2009 and published 28 April 2009 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords London : The Stationery Office Limited £price HL Paper 76 The European Union Committee The European Union Committee of the House of Lords considers EU documents and other matters relating to the EU in advance of decisions being taken on them in Brussels. It does this in order to influence the Government’s position in negotiations, and to hold them to account for their actions at EU level. The Government are required to deposit EU documents in Parliament, and to produce within two weeks an Explanatory Memorandum setting out the implications for the UK. The Committee examines these documents, and ‘holds under scrutiny’ any about which it has concerns, entering into correspondence with the relevant Minister until satisfied. Letters must be answered within two weeks. Under the ‘scrutiny reserve resolution’, the Government may not agree in the EU Council of Ministers to any proposal still held under scrutiny; reasons must be given for any breach. The Committee also conducts inquiries and makes reports. The Government are required to respond in writing to a report’s recommendations within two months of publication. If the report is for debate, then there is a debate in the House of Lords, which a Minister attends and responds to. The Committee -

Survey Report

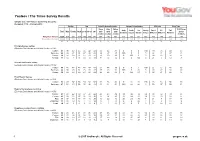

YouGov / The Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1054 Labour leadership electorate Fieldwork: 17th - 21st July 2015 Gender Age Joined Labour electorate… Current 1st preference 2010 vote Voter Type Since After Before TU Affiliates Andy Yvette Liz Jeremy David Ed Full Total Male Female 18-24 25-39 40-59 60+ 2015 2010 2010 and £3 Burnham Cooper Kendall Corbyn Miliband Miliband Members election election election members Weighted Sample 1054 528 526 128 210 346 371 354 210 461 216 162 93 353 206 176 832 171 Unweighted Sample 1054 534 520 77 224 369 384 359 205 461 215 165 87 363 168 208 823 182 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % First preference voting [Excludes Don't knows and Wouldn't votes; n=830] Corbyn 43 38 47 45 45 42 42 50 42 37 0 0 0 100 19 56 40 57 Burnham 26 26 27 31 27 26 25 25 27 27 100 0 0 0 32 21 27 21 Cooper 20 21 18 14 14 22 22 16 20 23 0 100 0 0 29 16 21 14 Kendall 11 15 7 11 14 10 11 9 12 14 0 0 100 0 21 7 12 8 Second preference voting [Excludes Don't knows and Wouldn't votes; n=815] Corbyn 44 41 48 46 48 43 43 51 44 39 0 0 7 100 21 57 41 60 Burnham 29 30 28 34 28 30 27 27 28 31 100 0 26 0 40 22 31 22 Cooper 26 29 24 20 24 28 29 22 28 30 0 100 67 0 39 21 28 18 Final Round Voting [Excludes Don't knows and Wouldn't votes; n=768] Corbyn 53 49 57 50 59 52 52 60 56 46 0 31 20 100 28 63 50 69 Burnham 47 51 43 50 41 48 48 40 44 54 100 69 80 0 72 37 50 31 Deputy first preference voting [Excludes Don't knows and Wouldn't votes; n=679] Watson 41 41 42 40 37 41 44 44 43 39 38 34 14 59 30 50 39 56 Creasy 21 20 22 25 32 19 15 21 21 20 22 24 20 19 23 20 23 11 Flint 17 17 18 17 15 16 20 16 22 16 20 24 34 7 21 8 17 18 Bradshaw 11 11 10 13 7 11 12 10 7 13 9 9 28 7 15 8 11 9 Eagle 10 11 9 6 9 13 9 9 7 12 11 9 5 9 11 14 11 6 Deputy second preference voting [Excludes Don't knows and Wouldn't votes; n=658] Watson 46 46 46 43 41 46 48 48 45 44 43 38 16 64 36 56 43 59 Creasy 22 21 24 26 34 22 16 23 23 21 23 26 22 20 23 22 25 12 Flint 19 19 19 17 16 18 21 17 23 18 22 25 35 8 24 11 19 19 Bradshaw 13 15 11 13 9 13 15 12 8 16 13 11 28 8 18 11 13 10 1 © 2015 YouGov plc.