Proposed Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5635/docket-no-fws-hq-es-2019-0009-ff09e21000-fxes11190900000-167-75635.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/10/2019 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2019-21478, and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Domestic and Foreign Species That Are Candidates for Listing as Endangered or Threatened; Annual Notification of Findings on Resubmitted Petitions; Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of review. SUMMARY: In this candidate notice of review (CNOR), we, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), present an updated list of plant and animal species that we regard as candidates for or have proposed for addition to the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended. Identification of candidate species can assist environmental planning efforts by providing advance notice of potential listings, and by allowing landowners and resource managers to alleviate threats and thereby possibly remove the need to list species as endangered or threatened. Even if we subsequently list a candidate species, the early notice provided here could result in more options for species management and recovery by prompting earlier candidate conservation measures to alleviate threats to the species. This document also includes our findings on resubmitted petitions and describes our 1 progress in revising the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants (Lists) during the period October 1, 2016, through September 30, 2018. -

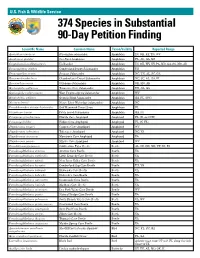

374 Species in Substantial 90-Day Petition Finding

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 374 Species in Substantial 90-Day Petition Finding Scientific Name Common Name Taxon/Validity Reported Range Ambystoma barbouri Streamside salamander Amphibian IN, OH, KY, TN, WV Amphiuma pholeter One-Toed Amphiuma Amphibian FL, AL, GA, MS Cryptobranchus alleganiensis Hellbender Amphibian IN, OH, WV, NY, PA, MD, GA, SC, MO, AR Desmognathus abditus Cumberland Dusky Salamander Amphibian TN Desmognathus aeneus Seepage Salamander Amphibian NC, TN, AL, SC, GA Eurycea chamberlaini Chamberlain's Dwarf Salamander Amphibian NC, SC, AL, GA, FL Eurycea tynerensis Oklahoma Salamander Amphibian OK, MO, AR Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander Amphibian TN, AL, GA Gyrinophilus subterraneus West Virginia Spring Salamander Amphibian WV Haideotriton wallacei Georgia Blind Salamander Amphibian GA, FL (NW) Necturus lewisi Neuse River Waterdog (salamander) Amphibian NC Pseudobranchus striatus lustricolus Gulf Hammock Dwarf Siren Amphibian FL Urspelerpes brucei Patch-nosed Salamander Amphibian GA, SC Crangonyx grandimanus Florida Cave Amphipod Amphipod FL (N. and NW) Crangonyx hobbsi Hobb's Cave Amphipod Amphipod FL (N. FL) Stygobromus cooperi Cooper's Cave Amphipod Amphipod WV Stygobromus indentatus Tidewater Amphipod Amphipod NC, VA Stygobromus morrisoni Morrison's Cave Amphipod Amphipod VA Stygobromus parvus Minute Cave Amphipod Amphipod WV Cicindela marginipennis Cobblestone Tiger Beetle Beetle AL, IN, OH, NH, VT, NJ, PA Pseudanophthalmus avernus Avernus Cave Beetle Beetle VA Pseudanophthalmus cordicollis Little -

The Giant Salamanders (Cryptobranchidae): Part B

Copyright: © This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial– NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits conditional use for non-commercial and education purposes, provided the Amphibian and Reptile Conservation 5(4): 30-50. original author and source are credited, and prohibits the deposition of material from www.redlist-arc.org, including PDFs, images, or text onto other websites without permission of the International Chapter at www.redlist-arc.org. The giant salamanders (Cryptobranchidae): Part B. Biogeography, ecology and reproduction 1Robert K Browne, 2Hong Li, 3Zhenghuan Wang, 4Sumio Okada, 5Paul Hime, 6Amy McMillan, 7Minyao Wu, 8Raul Diaz, 9Dale McGinnity, 10Jeffrey T. Briggler 1Sustainability America, Sarteneja, Belize. 2Polytechnic Institute of New York University, NYC, USA. 3School of Life Sciences, East China Normal University, 200062, Shanghai, Peoples Republic of China. 4Laboratory of Biology, Department of Regional Environment, Tottori University, Tottori 680-8551, Japan. 5Department of Biology, University of Kentucky, Department of Biology, Lexington, Kentucky 40506, USA. 6SUNY Buffalo State, Buffalo, New York 14222, USA. 7Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, 710062, Shaanxi Province, Peoples Republic of China. 8La Sierra University, Department of Biology, 4500 Riverwalk Parkway, Riverside, California 92515, USA 9Nashville Zoo, Nashville, Tennessee 37189, USA. 10Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri 65109, USA. Abstract - The Chinese (Andrias davidianus) and Japanese (A. japonicus) giant salamanders far exceed any other living amphibians in size, with the North American giant salamander (Hellbender; Cryptobranchus alleganiensis) also being one of the world’s largest amphibians. The sustainable management of cryptobranchids requires knowledge of cryptobranchid biogeography, ecology and reproduction in concert with other scientific fields. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Hickory Nut Gorge Green Salamander (Aneides caryaensis) Photo by Austin Patton 2014 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. The list is published periodically, generally every two years. -

NC Herps -14- April 2019

NC Herps -14- April 2019 SPEAKERS Dave Beamer is the Lead Researcher and a Biology Instructor at Nash Community College in Rocky Mount, NC, where he teaches Introduction to Biology for science majors’ students. In addition, he teaches Regional Natural History and Field Biology courses that provide an opportunity to showcase the spectacular floral and faunal diversity of North Carolina to students. He is dedicated to providing opportunities to undergraduate students to conduct original research projects that help forward the knowledge and understanding of North Carolina’s salamander diversity. One of his goals as an instructor and mentor is to foster an appreciation of biodiversity and a stronger understanding of science and the scientific process amongst his students. He is currently funded by the National Science Foundation to study speciation processes in dusky salamanders. As part of the broader impacts of this grant, and through support by a Duke Energy grant, he has been conducting a year-long after school K-12 program entitled “Using Biotechnology to Uncover Biodiversity.” Jeff Beane is Herpetology Collection Manager for the North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, where he has been employed since 1985. A native of Asheboro, he holds a B.S. in Zoology from North Carolina State University (1982). A hard-core member of NCHS since 1982, he has served as its newsletter editor since 1986, and has served on most of the Society’s committees. An old-school naturalist, he is active in several other natural history and conservation groups and initiatives, including NCPARC, Wake Audubon, and Sandhills Natural History Society. -

Download the Parcas Criteria and Implementation Plan Here!

Model Criteria and Implementation Guidance for a Priority Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Area (PARCA) System in the U.S.A. V.4 October 2012 PARCA Task Team Prepared by Ron Sutherland and Phillip deMaynadier In collaboration with National PARC’s "Priority Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Areas" Task Team: Co-Leads: Ron Sutherland , Wildlands Network Phillip deMaynadier, Maine Dept. of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife Team Members: Margaret Trani Griep, U.S. Forest Service Southern Region Audrey Hatch, formerly Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Randy Jennings, Western New Mexico University Karen Kinkead , Iowa Dept. of Natural Resources Priya Nanjappa, Assoc. of Fish & Wildlife Agencies Cover Photographs: Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) – J. Mays Coastal Tailed Frog (Ascaphus truei) – B. McCreary Eastern Indigo Snake (Drymarchon couperi) – J.D. Willson Blue-spotted Salamander (Ambystoma laterale) – L. Kenney Reticulate Gila Monster (Heloderma s. suspectum) – K. Stohlgren Suggested citation: R. Sutherland and P. deMaynadier. 2012. Model Criteria and Implementation Guidance for a Priority Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Area (PARCA) System in the USA. Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, Technical Publication PARCA-1. 28 pp. 2 V.4 October 2012 PARCA Task Team Contents: Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………………….....................…...3 Introduction…………..……. ……………………………………………………………………………………3 Criteria for PARCA Selection…………………… …………………………………………………………5 Criteria Overview and PARCA Scale.............……………………………………………………….…..8 -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 109/Wednesday, June 9, 2021

30688 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 109 / Wednesday, June 9, 2021 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR from which the maps are generated are present or threatened destruction, included in the administrative record modification, or curtailment of its Fish and Wildlife Service and are available at http:// habitat or range; (B) overutilization for www.regulations.gov at Docket No. commercial, recreational, scientific, or 50 CFR Part 17 FWS–R4–ES–2018–0092, and at the educational purposes; (C) disease or [Docket No. FWS–R4–ES–2018–0092; Raleigh Ecological Services Field Office predation; (D) the inadequacy of FF09E21000 FXES11110900000 212] (https://www.fws.gov/raleigh; street existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) address provided above). Any other natural or manmade factors RIN 1018–BC28 additional tools or supporting affecting its continued existence. We have determined that habitat Endangered and Threatened Wildlife information that we developed for this degradation (Factor A), resulting from and Plants; Threatened Species Status critical habitat designation will also be available at the Fish and Wildlife the cumulative impacts of land use With Section 4(d) Rule for Neuse River change and associated watershed-level Waterdog, Endangered Species Status Service website and Field Office identified above, and may also be effects on water quality, water quantity, for Carolina Madtom, and Designations habitat connectivity, and instream of Critical Habitat included in the preamble and at http:// www.regulations.gov. habitat suitability, poses the largest risk AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Pete to the future viability of both species. Interior. Benjamin, Field Supervisor, U.S. -

Inventory of Natural Areas and Wildlife Habitats for Orange County, North Carolina

Inventory of Natural Areas and Wildlife Habitats for Orange County, North Carolina Dawson Sather and Stephen Hall (1988) Updated by Bruce Sorrie and Rich Shaw (2004) December 2004 Orange County Environment & Resource Conservation Department North Carolina Natural Heritage Program NC Natural Heritage Trust Fund Inventory of Natural Areas and Wildlife Habitats for Orange County, North Carolina Dawson Sather and Stephen Hall (1988) Updated by Bruce Sorrie and Rich Shaw (2004) December 2004 Orange County Environment & Resource Conservation Department North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Funded by Orange County, North Carolina NC Natural Heritage Trust Fund Prepared by Rich Shaw and Margaret Jones Orange County Environment and Resource Conservation Department Hillsborough, North Carolina For further information or to order copies of the inventory, please contact: Orange County ERCD P.O. Box 8181 Hillsborough, NC 27278 919/245-2590 or The North Carolina Natural Heritage Program 1601 Mail Service Center Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org Table of Contents Page PREFACE....................................................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................ 1 Information Sources............................................................................................................ -

DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 01/03/2018 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2017-28386, and on FDsys.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket Nos. FWS–R4–ES–2016–0029 and FWS–R4–ES–2016–0031; 4500030113] RIN 1018–BA78; RIN 1018–BA79 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Species Status for Black Warrior Waterdog and Designation of Critical Habitat AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), determine endangered species status under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (Act), as amended for the Black Warrior waterdog (Necturus alabamensis) and designate critical habitat. The effect of this regulation will be to add this species to the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and designate critical habit for this species. In total, approximately 673 kilometers (420 miles) of streams and rivers in Blount, , Etowah, Jefferson, Lawrence, Marshall, Tuscaloosa, Walker, and Winston Counties, Alabama, fall within the boundaries of the critical habitat designation. DATES: This rule is effective [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER THE DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESSES: This final rule is available on the Internet at http://www.regulations.gov and http://www.fws.gov/daphne/. Comments, materials, and documentation that we considered in this rulemaking will be available by appointment, during normal business hours, at: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alabama Ecological Services Field Office, 1208 Main Street, Daphne, AL 36526; by telephone 251–441–5184; or by facsimile 251–441–6222. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 99/Wednesday, May 22, 2019

23644 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 99 / Wednesday, May 22, 2019 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR shown in FOR FURTHER INFORMATION commercial data available concerning CONTACT by July 8, 2019. the status of the species, including the Fish and Wildlife Service ADDRESSES: You may submit comments impacts of past, present, and future by one of the following methods: factors (both negative and beneficial) 50 CFR Part 17 (1) Electronically: Go to the Federal affecting each species. Both SSA reports [Docket No. FWS–R4–ES–2018–0092; eRulemaking Portal: http:// underwent independent peer review by 4500030113] www.regulations.gov. In the Search box, scientists with expertise in fish or enter FWS–R4–ES–2018–0092, which is amphibian biology, habitat RIN 1018–BC28 the docket number for this rulemaking. management, and stressors (factors negatively affecting the species) to the Endangered and Threatened Wildlife Then, in the Search panel on the left side of the screen, under the Document species. The SSA reports and other and Plants; Threatened Species Status materials relating to this proposal can be With Section 4(d) Rule for Neuse River Type heading, check the Proposed Rules box to locate this document. You may found on the Southeast Region website Waterdog and Endangered Species at https://www.fws.gov/southeast/ and Status for Carolina Madtom and submit a comment by clicking on ‘‘Comment Now!’’ at http://www.regulations.gov under Proposed Designations of Critical Docket No. FWS–R4–ES–2018–0092. Habitat (2) By hard copy: Submit by U.S. mail or hand-delivery to: Public Comments Executive Summary AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Processing, Attn: FWS–R4–ES–2018– Interior. -

Conservation Assessment for Ozark Hellbender (Cryptobranchus Alleganiensis Bishopi Grobman)

Conservation Assessment for Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi Grobman) Female on the left (bigger) and male on the right (smaller). Photo credit: Dr. Yue-wern Huang USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region Information compiled by Larry L. Furniss 9/25/2003 Mark Twain National Forest 401 Fairgrounds Road Rolla, MO 65401 This document is undergoing peer review, comments welcome. CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS Jeff Briggler Missouri Department of Conservation [email protected] Susan Rogers U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [email protected] Larry Furniss U.S. Forest Service [email protected] Yue-wern Huang University of Missouri- Rolla [email protected] Alicia Mathis Southwest Missouri State University [email protected] Stan Trauth Arkansas State University [email protected] Ben Wheeler Arkansas State University [email protected] This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi Grobman. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject community and associated taxa, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service - Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Table -

Species Status Assessment Report for the Neuse River Waterdog (Necturus Lewisi) Version 1.1

Species Status Assessment Report for the Neuse River Waterdog (Necturus lewisi) Version 1.1 LITERATURE CITED Aktar, M.W., Dwalpayan, S., and A. Chowdhury. 2009. Impact of pesticide use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards. Interdisciplinary Toxicology,Vol 2(1):1-12. Alig, R. S.Stewart, D.Wear, S.Stein, and D.Nowak. 2010. Conversions of Forest Land: Trends, Determinants, Projections, and Policy Considerations. Chapter in Advances in Threat Assessment and Their Application to Forest and Rangeland Management. U.S. Forest Service General Technical Report PNW-GTR-802. https://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/gtr802/Vol1/pnw_gtr802vol1_alig.pdf (accessed: 2/15/2017) Allan, J.D. 1995. Stream Ecology: Structure and Function of Running Waters. Chapman & Hall. New York. Allan, J.D., D.L. Erickson, and J.Fay. 1997. The influence of catchment land use on stream integrity across multiple scales. Freshwater Biology 37:149-161. Allen, A.W., Y.K. Bernal, and R.J. Moulton. 1996. Pine Plantations and Wildlife in the Southeastern United States: An Assessment of Impacts and Opportunities. Information and Technology Report 3, U.S. Department of Interior, Washington, D.C. 40pp. http://www.nwrc.usgs.gov/wdb/pub/others/1996_03.pdf (Accessed: 2/9/2017) Arabshahi, I. and C. Raines. 2012. Defense, National Security & Climate Change: Building Resilience and Identifying Opportunities Related to Water, Energy and Extreme Events. Workshop Synthesis Report. Association of Climate Change Officers. 33pp. Ashton, Jr. R.E. 1985. Field and Laboratory Observations on Microhabitat Selection, Movements, and Home Range of Necturus lewisi (Brimley). Brimleyana 15:83-106. Ashton Jr., R.E.