Situation Summary of Extractive Industries in the Gloucester-Stroud Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scenic Drives Gloucester New South Wales DRIVE 2: GLOUCESTER TOPS

Enter this URL to view the map on your mobile device: https://goo.gl/maps/c7niuMo3oTr Scenic Drives Gloucester New South Wales DRIVE 2: GLOUCESTER TOPS Scenic Drive #2: Gloucester Tops return via Faulkland Length: 115km Start: Visitor Information Centre at 27 Denison Street End: Gloucester township Featuring: Gloucester River valley, Gloucester Tops, Barrington Tops National Park, Andrew Laurie Lookout, Gloucester Falls, Gloucester River, Faulkland and multiple river crossings on concrete causeways (caution advised). Gloucester Visitor Information Centre 27 Denison Street, Gloucester New South Wales AUSTRALIA T: 02 6538 5252 F: 02 6558 9808 [email protected] www.gloucestertourism.com.au Scenic Drive #2 – Gloucester Tops And on the way you’ll see beautiful rural landscapes and The Antarctic Beech Forest Track features cool tem- cross numerous river fords with picnic and swimming perate rainforest with the canopy of ancient trees If you only have half a day then this offers you a taste spots before returning to Gloucester or continuing your towering above the tree ferns and a damp carpet of of world heritage wilderness. Gloucester Tops Nation- journey towards the Pacific Highway. moss on the forest floor, rocks and logs. The longer al Park is the easternmost section of Barrington Tops walking track option takes you to a mossy cascade and is the closest part of this stunning wilderness to Along Gloucester Tops Road for the next 40km you’ll with the purest mountain water. As you step be- Gloucester. track the Gloucester River as the road winds through hind the curtain of green you’ll feel like you’re on productive farming valleys surrounded by forest-clad the film set of Lord Of The Rings. -

'Geo-Log' 2016

‘Geo-Log’ 2016 Journal of the Amateur Geological Society of the Hunter Valley Inc. Contents: President’s Introduction 2 Gloucester Tops 3 Archaeology at the Rocks 6 Astronomy Night 8 Woko National Park 11 Bar Beach Geology and the Anzac Walkway 15 Crabs Beach Swansea Heads 18 Caves and Tunnels 24 What Rock is That? 28 The Third Great Numbat Mystery Reconnaissance Tour 29 Wallabi Point and Lower Manning River Valley Geology 32 Geological Safari, 2016 36 Social Activities 72 Geo-Log 2016 - Page 1 President’s Introduction. Hello members and friends. I am pleased and privileged to have been elected president of AGSHV Inc. for 2016. This is an exciting challenge to be chosen for this role. Hopefully I have followed on from where Brian has left off as he has left big shoes to fill. Brian and Leonie decided to relinquish their long held posts as President and Treasurer (respectively) after many years of unquestionable service to our society, which might I say, was carried out with great efficiency and grace. They have set a high standard. Thank you Brian and Leonie. We also welcomed a new Vice President, Richard Bale and new Treasurer John Hyslop. Although change has come to the executive committee the drive for excellence has not been diminished. Brian is still very involved with organising and running activities as if nothing has changed. The “What Rock Is That” teaching day Brian and Ron conducted (which ended up running over 2 days) at Brian’s home was an outstanding success. Everyone had samples of rocks, with Brian and Ron explaining the processes involved in how these rocks would have formed, and how to identify each sample, along with copious written notes and diagrams. -

Keeping up with Council

KEEPING UP APRIL WITH COUNCIL 2020 OUR RESPONSE TO COVID-19 During this challenging time the safety and well-being of our community, staff and volunteers remains our priority. In line with Federal and State Government measures to reduce the spread of the virus, we are temporarily changing the way we deliver services in our community. Essential services such as water and sewer services, road maintenance and rubbish collection will continue, but facilities delivering face-to-face services will be closed until further notice. These include the Manning Entertainment Centre; all Council owned pools including YMCA facilities in Taree, Forster and Wingham; all Customer Service Centres, Libraries and Visitor Bushfire recovery Information Centres; and the Manning Regional Art Gallery. Supporting our community to rebuild after the At the time of writing, our Gloucester Customer Service Centre devastating fires of late 2019 is the focus of will be closed, but the Service NSW and Services Australia our bushfire recovery taskforce. (Centrelink) agencies that operate from our Gloucester office The team includes building, environmental will remain open. health and waste specialists who are working You can still do business with us - we will remain accessible together to support property owners in the and open for business via phone, email and online. Our waste clean-up and rebuilding process. management centres also remain open at this point. Refer to our All rebuilding fees for those properties website to stay up-to-date on service delivery. assessed as destroyed by the Rural Fire It’s important to understand our response is changing as the Service’s building impact assessment team situation evolves. -

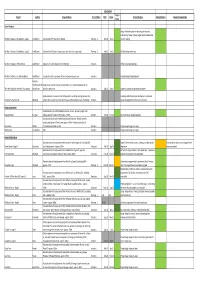

2020-21 CWP Project Status.Xlsx

Construction Project Project Location Scope of Works Current Phase Start Finish Current Progress Financial Status Financial Commentary Status Special Projects Design finalised in prep for relocating services and commencing tender process, target report to December Northern Gateway ‐ Roundabout ‐ stage 1 Cundletown Construction of Princes St roundabout Planning ‐ 2Dec‐20 Apr‐21 Council meeting. Northern Gateway ‐ Roundabout ‐ stage 2 Cundletown Construction of 2 lanes of bypass road up to industrial access road Planning ‐ 2Apr‐21 Jun‐21 Detailed design underway. Northern Gateway ‐ Off/On Ramps Cundletown Upgrade of on/off ramps for Pacific Highway Initiation TfNSW is developing design. Northern Gateway ‐ Cundletown Bypass Cundletown Construction of the remainder of the Cundletown bypass road Initiation Concept design being prepared. Rainbow Flat/Darwank/Ha Scope of works to be finalised ‐ provisionally a 2 lane lane roundabout for an The Lakes Way/Blackhead Rd ‐ Roundabout llidays Point 80km/hr speed zone Initiation Apr‐21 Sep‐21 Scope and concept design being developed. Replacement of a low level timber bridge with a new bridge at a higher level that Awaiting notification of grant funding to proceed with Cedar Party Creek Bridge Wingham reduces flood imapcts and services the heavy vehicle network more effeectively. Initiation design development for the current proposal. Urban Construction Combined with Horse Point Road (rural construction) ‐ 6m seal ‐ project is to Dogwood Road Bungwahl reduce sediment loads on Smiths Lake ‐ 1400m. Initiation Oct‐20 Dec‐20 Pavement design being developed. Construction of a bitumen sealed road between Saltwater Rd and currently constructed section of Forest Lane, approx. 600m. Phased construction of Forest Lane Old Bar intersection with Saltwater Rd. -

Statement of Environmental Effects Bowens Road North Open Cut

BOWENS ROAD NORTH OPEN CUT JUNE 2010 MODIFICATION STATEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS BOWENS ROAD NORTH OPEN CUT JUNE 2010 MODIFICATION STATEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS JUNE 2010 Project No. GCL-09-11 Document No. 00346359 Bowens Road North Open Cut – June 2010 Modification Statement of Environmental Effects TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 GENERAL 1 1.1.1 Existing Operations 1 1.1.2 June 2010 Modification Overview 5 1.2 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 5 1.2.1 Environmental Planning Instruments 9 1.2.2 Other Approvals 15 1.3 CONSULTATION 15 1.3.1 State and Local Government Agencies 15 1.3.2 Public Consultation 16 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THIS SEE 18 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED MODIFICATION 19 2.1 MINING METHOD AND OPERATING HOURS 19 2.2 COAL AND WASTE ROCK PRODUCTION 19 2.3 CHPP REJECT MANAGEMENT 20 2.4 WORKFORCE 20 3 ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW 21 3.1 FLORA AND FAUNA 21 3.2 NOISE 29 3.2.1 Existing Environment 29 3.2.2 Potential Impacts 31 3.2.3 Mitigation Measures and Management 31 3.3 AIR QUALITY 32 3.3.1 Existing Environment 32 3.3.2 Potential Impacts 33 3.3.3 Mitigation Measures and Management 33 3.4 GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS 34 3.4.1 Existing Environment 34 3.4.2 Potential Impacts 34 3.4.3 Mitigation Measures and Management 34 3.5 SURFACE WATER RESOURCES 35 3.5.1 Existing Environment 35 3.5.2 Potential Impacts 35 3.5.3 Mitigation Measures and Management 36 3.6 GROUNDWATER RESOURCES 36 3.6.1 Existing Environment 36 3.6.2 Potential Impacts 36 3.6.3 Mitigation Measures and Management 37 3.7 GEOCHEMISTRY 37 3.8 LAND RESOURCES 37 3.8.1 Existing -

Annual Review 2015

Annual Review 2015 Duralie Coal Pty Ltd Page 2 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 CONSENTS, LEASES, LICENCES AND OTHER APPROVALS ......................................... 7 1.1.1 Status of Leases, Licences, Permits and Approvals ...................................................... 7 1.1.2 Amendments to Approvals/Licences during the Reporting Period ................................. 8 1.2 MINE CONTACTS .................................................................................................................. 8 1.3 ACTIONS REQUIRED AT PREVIOUS AR REVIEW ............................................................. 8 1.4 AUDITS ................................................................................................................................. 10 2 SUMMARY OF OPERATIONS ................................................................................................. 10 2.1 EXPLORATION .................................................................................................................... 10 2.1.1 Estimated Mine Life ...................................................................................................... 11 2.2 MINING ................................................................................................................................. 11 2.2.1 Mining Equipment and Method ..................................................................................... 11 2.2.2 ROM -

Duralie Coal Mine

Annual Review 2013 DURALIE COAL MINE ANNUAL REVIEW Reporting Period: 1st July 2012 to 30th June 2013 Name of mine: Duralie Coal Mine. Mining Titles/Leases: ML1427, ML1646 MOP Commencement date December 2010 MOP Completion date December 2017 AR Commencement date 1st July 2012 AR End date 30th June 2013 Name of leaseholder: Duralie Coal Ltd Name of mine operator (if different): Leighton Mining Reporting Officer: Mr Tony Dwyer Tittle: Manager-Environment and Communiity Signature ………………………………………………… Date Duralie Coal Pty Ltd Page 2 Duralie Coal Annual Review Year Ending June 2013 Prepared by CARBON BASED ENVIRONMENTAL PTY LTD on behalf of Duralie Coal Pty Ltd Carbon Based Environmental Pty Ltd Unit 3, 2 Enterprise Crescent Singleton NSW 2330 Phone: 02 6571 3334 Fax: 02 6571 3335 Emaill:[email protected] Annual Review June 2013 Duralie Coal Pty Ltd Page 3 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 COAL PRODUCTS AND MARKETS ..................................................................................... 7 1.2 CONSENTS, LEASES, LICENCES AND OTHER APPROVALS ......................................... 8 1.2.1 Status of Leases, Licences, Permits and Approvals ...................................................... 8 1.2.2 Amendments to Approvals/Licences during the Reporting Period ............................... 10 1.3 MINE CONTACTS ............................................................................................................... -

Functioning and Changes in the Streamflow Generation of Catchments

Ecohydrology in space and time: functioning and changes in the streamflow generation of catchments Ralph Trancoso Bachelor Forest Engineering Masters Tropical Forests Sciences Masters Applied Geosciences A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences Trancoso, R. (2016) PhD Thesis, The University of Queensland Abstract Surface freshwater yield is a service provided by catchments, which cycle water intake by partitioning precipitation into evapotranspiration and streamflow. Streamflow generation is experiencing changes globally due to climate- and human-induced changes currently taking place in catchments. However, the direct attribution of streamflow changes to specific catchment modification processes is challenging because catchment functioning results from multiple interactions among distinct drivers (i.e., climate, soils, topography and vegetation). These drivers have coevolved until ecohydrological equilibrium is achieved between the water and energy fluxes. Therefore, the coevolution of catchment drivers and their spatial heterogeneity makes their functioning and response to changes unique and poses a challenge to expanding our ecohydrological knowledge. Addressing these problems is crucial to enabling sustainable water resource management and water supply for society and ecosystems. This thesis explores an extensive dataset of catchments situated along a climatic gradient in eastern Australia to understand the spatial and temporal variation -

Context Statement for the Gloucester Subregion, PDF, 11.22 MB

Context statement for the Gloucester subregion Product 1.1 from the Northern Sydney Basin Bioregional Assessment 28 May 2014 A scientific collaboration between the Department of the Environment, Bureau of Meteorology, CSIRO and Geoscience Australia The Bioregional Assessment Programme The Bioregional Assessment Programme is a transparent and accessible programme of baseline assessments that increase the available science for decision making associated with coal seam gas and large coal mines. A bioregional assessment is a scientific analysis of the ecology, hydrology, geology and hydrogeology of a bioregion with explicit assessment of the potential direct, indirect and cumulative impacts of coal seam gas and large coal mining development on water resources. This Programme draws on the best available scientific information and knowledge from many sources, including government, industry and regional communities, to produce bioregional assessments that are independent, scientifically robust, and relevant and meaningful at a regional scale. The Programme is funded by the Australian Government Department of the Environment. The Department of the Environment, Bureau of Meteorology, CSIRO and Geoscience Australia are collaborating to undertake bioregional assessments. For more information, visit <www.bioregionalassessments.gov.au>. Department of the Environment The Office of Water Science, within the Australian Government Department of the Environment, is strengthening the regulation of coal seam gas and large coal mining development by ensuring that future decisions are informed by substantially improved science and independent expert advice about the potential water related impacts of those developments. For more information, visit <www.environment.gov.au/coal-seam-gas-mining/>. Bureau of Meteorology The Bureau of Meteorology is Australia’s national weather, climate and water agency. -

Gloucester and Barrington Tops

Gloucester and Barrington Tops 5 Day Tour Departing: Monday 20 May 2019 Returning: Friday 24 May 2019 TOUR COST: $1095.00 per person Twin/Double Share $1310.00 Sole Occupancy Please call the office for Direct Deposit details PICK UP TIMES: 7.40am Crawford Street, Queanbeyan 8.20am West Row Bus Stop, City 8.00am Bay 3, Woden Bus Interchange 8.30am Riggall Place, Lyneham Day 1: (LD) CANBERRA TO GLOUCESTER: Monday 20 May 2019 The charming country town of Gloucester is nestled in a valley of surpassing loveliness. The Gloucester River winds its way around the base of the picturesque mountains, where we’ll be staying. Inhale the clean, fresh air as we explore this wilderness without having to travel too far afield. Bags paced, coach loaded we depart Canberra and head through Sydney, making a lunch stop along the way. We journey through the scenic Bucketts Way into Gloucester and the Gloucester Country Lodge. Adjacent to the sweeping fairways of the Gloucester Golf Club, our hotel is in an idyllic, quiet and peaceful rural setting where you can unpack, unwind and relax into your surroundings. Gloucester Country Lodge, Gloucester | 02 6558 1812 Day 2: (BLD) GLOUCESTER: Tuesday 21 May 2019 Waking refreshed, we are joined on the coach by a local expert who will introduce us to this beautiful area. Visiting Gloucester Museum we’ll discover Captain Thunderbolt, a famous bushranger who used the town to hide. Discover artefacts, the stunning pressed-metal ceilings and the secret explosives store from the goldrush era. At the delightful Hillview Herb Farm we smell, touch and taste an amazing array of herbs in a peaceful garden setting. -

Nsw Estuary and River Water Levels Annual Summary 2015-2016

NSW ESTUARY AND RIVER WATER LEVELS ANNUAL SUMMARY 2015–2016 Report MHL2474 November 2016 prepared for NSW Office of Environment and Heritage This page intentionally blank NSW ESTUARY AND RIVER WATER LEVELS ANNUAL SUMMARY 2015–2016 Report MHL2474 November 2016 Peter Leszczynski 110b King Street Manly Vale NSW 2093 T: 02 9949 0200 E: [email protected] W: www.mhl.nsw.gov.au Cover photograph: Coraki photo from the web camera, Richmond River Document control Issue/ Approved for issue Author Reviewer Revision Name Date Draft 21/10/2016 B Tse, MHL S Dakin, MHL A Joyner 26/10/2016 Final 04/11/2016 M Fitzhenry, OEH A Joyner 04/11/2016 © Crown in right of NSW through the Department of Finance, Services and Innovation 2016 The data contained in this report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Manly Hydraulics Laboratory and the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage permit this material to be reproduced, for educational or non-commercial use, in whole or in part, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. While this report has been formulated with all due care, the State of New South Wales does not warrant or represent that the report is free from errors or omissions, or that it is exhaustive. The State of NSW disclaims, to the extent permitted by law, all warranties, representations or endorsements, express or implied, with regard to the report including but not limited to, all implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement. -

Scenic Drives #Barringtoncoast Potaroo Falls, Tapin Tops NP Shellydark Beach, Point Aboriginalpacific Palms Place Ford Over Gloucester River Jimmys Beach

EXPLORE & DISCOVER barringtoncoast.com.au 1800 802 692 @barringtoncoast Scenic drives #barringtoncoast Potaroo Falls, Tapin Tops NP ShellyDark Beach, Point AboriginalPacific Palms Place Ford over Gloucester River Jimmys Beach As crystal clear water tumbles from the rugged peaks, it breathes life Breckenridge Channel, Forster into our land; for this is the Barrington Coast - A place where the leaves touch the waters, from the mountains to the sea. Ellenborough Aussie Ark, Falls, Elands Thunderbolts Lookout, Barrington Tops Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse, Seal Rocks Barrington Tops Gloucester Tops Cover: Diamond Head, Crowdy Bay National Park Barrington Coast is the destination brand of MidCoast Council barringtoncoast.com.au Lakes to lookouts Myalls of beaches Historical hinterland Barrington explorer Valley to falls Sea to summit -The extraordinary coastal lakes and -Explore the superb southern precinct -Follow the footsteps of the European -Explore the world heritage wilderness -Exploring the beautiful rural landscapes -From seashore to mountain top, headlands of our treasured national of Myall Lakes National Park. Wander pioneers from the Australian Agricultural of Barrington Tops. At the highest point of the Manning prepares you for the discover the beauty of the Barrington parks are matched with picture- coastal woodlands bounded by long Company. You’ll explore the pretty of the Barrington Coast you’ll find spectacle of Ellenborough Falls, easily Coast. You’ll explore sanctuaries perfect beaches of white and gold. isolated beaches and dig your toes into valleys and villages of their renowned trails leading to ancient forests, mossy one of Australia’s top ten waterfalls. for abundant wildlife, deserted Inland you’ll discover forests of deep the white sands on the southern shores one million acre estate that now forms cascades, lookouts across endless green Potaroo Falls is a delicious second beaches, coastal wetlands, waterfalls green including the tallest of the tall.