Terrestrial Fauna of the South Goast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Degradation and the Australian Agricultural Industry

LAND DEGRADATION AND THE AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY Paul Gretton Umme Salma STAFF INFORMATION PAPER 1996 INDUSTRY COMMISSION © Commonwealth of Australia 1996 ISBN This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial usage or sale requires prior written permission from the Australian Government Publishing Service. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Commonwealth Information Services, AGPS, GPO Box 84, Canberra ACT 2601. Enquiries Paul Gretton Industry Commission PO Box 80 BELCONNEN ACT 2616 Phone: (06) 240 3252 Email: [email protected] The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the Industry Commission. Forming the Productivity Commission The Federal Government, as part of its broader microeconomic reform agenda, is merging the Bureau of Industry Economics, the Economic Planning Advisory Commission and the Industry Commission to form the Productivity Commission. The three agencies are now co- located in the Treasury portfolio and amalgamation has begun on an administrative basis. While appropriate arrangements are being finalised, the work program of each of the agencies will continue. The relevant legislation will be introduced soon. This report has been produced by the Industry Commission. CONTENTS Abbreviations v Preface vii Overview -

Insights Into Australian Bat Lyssavirus in Insectivorous Bats of Western Australia

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Article Insights into Australian Bat Lyssavirus in Insectivorous Bats of Western Australia Diana Prada 1,*, Victoria Boyd 2, Michelle Baker 2, Bethany Jackson 1,† and Mark O’Dea 1,† 1 School of Veterinary Medicine, Murdoch University, Perth, WA 6150, Australia; [email protected] (B.J.); [email protected] (M.O.) 2 Australian Animal Health Laboratory, CSIRO, Geelong, VIC 3220, Australia; [email protected] (V.B.); [email protected] (M.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-893607418 † These authors contributed equally. Received: 21 February 2019; Accepted: 7 March 2019; Published: 11 March 2019 Abstract: Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV) is a known causative agent of neurological disease in bats, humans and horses. It has been isolated from four species of pteropid bats and a single microbat species (Saccolaimus flaviventris). To date, ABLV surveillance has primarily been passive, with active surveillance concentrating on eastern and northern Australian bat populations. As a result, there is scant regional ABLV information for large areas of the country. To better inform the local public health risks associated with human-bat interactions, this study describes the lyssavirus prevalence in microbat communities in the South West Botanical Province of Western Australia. We used targeted real-time PCR assays to detect viral RNA shedding in 839 oral swabs representing 12 species of microbats, which were sampled over two consecutive summers spanning 2016–2018. Additionally, we tested 649 serum samples via Luminex® assay for reactivity to lyssavirus antigens. Active lyssavirus infection was not detected in any of the samples. -

DPIRD Annual Report 2020

Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Annual Report 2020 Page i Statement of compliance For year ended 30 June 2020 Hon. Alannah MacTiernan MLC Minister for Regional Development; Agriculture and Food and Hon. Peter Tinley AM MLA Minister for Fisheries In accordance with section 63 of the Financial Management Act 2006, I hereby submit for your information and presentation to Parliament, the annual report of the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development for the reporting period ended 30 June 2020. The annual report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Financial Management Act 2006 and also fulfils reporting obligations under the Fish Resources Management Act 1994 and Soil and Land Conservation Act 1945. Mr David (Ralph) Addis Director General Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Annual Report 2020 Page ii Contact Postal: Locked Bag 4, Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983 Permission to reuse the logo must be obtained from the Street address: 3 Baron-Hay Court, South Perth WA 6151 Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. Internet: dpird.wa.gov.au Important disclaimer Email: [email protected] Telephone: +61 1300 374 731 The Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development and the State of ISSN 2209-3427 (Print) Western Australia accept no liability whatsoever by reason of ISSN 2209-3435 (Online) negligence or otherwise arising from the use or release of this Creative Commons Licence information or any part of it. The DPIRD annual report is licensed under a Creative Compliments/complaints Commons Attribution 3.0 Australian Licence. -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

Phylogenetic Structure of Vertebrate Communities Across the Australian

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2013) 40, 1059–1070 ORIGINAL Phylogenetic structure of vertebrate ARTICLE communities across the Australian arid zone Hayley C. Lanier*, Danielle L. Edwards and L. Lacey Knowles Department of Ecology and Evolutionary ABSTRACT Biology, Museum of Zoology, University of Aim To understand the relative importance of ecological and historical factors Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079, USA in structuring terrestrial vertebrate assemblages across the Australian arid zone, and to contrast patterns of community phylogenetic structure at a continental scale. Location Australia. Methods We present evidence from six lineages of terrestrial vertebrates (five lizard clades and one clade of marsupial mice) that have diversified in arid and semi-arid Australia across 37 biogeographical regions. Measures of within-line- age community phylogenetic structure and species turnover were computed to examine how patterns differ across the continent and between taxonomic groups. These results were examined in relation to climatic and historical fac- tors, which are thought to play a role in community phylogenetic structure. Analyses using a novel sliding-window approach confirm the generality of pro- cesses structuring the assemblages of the Australian arid zone at different spa- tial scales. Results Phylogenetic structure differed greatly across taxonomic groups. Although these lineages have radiated within the same biome – the Australian arid zone – they exhibit markedly different community structure at the regio- nal and local levels. Neither current climatic factors nor historical habitat sta- bility resulted in a uniform response across communities. Rather, historical and biogeographical aspects of community composition (i.e. local lineage per- sistence and diversification histories) appeared to be more important in explaining the variation in phylogenetic structure. -

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

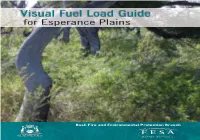

Visual Fuel Load Guide Esperance Plains

Visual Fuel Load Guide for Esperance Plains Bush Fire and Environmental Protection Branch Visual Fuel Load Guide for Esperance Plains Bioregion and part of the Jarrah Forest Bioregion Contents Introduction 2 Esperance Plain and Jarrah Forest Bioregions 2 Methods of fuel sampling 3 How to use this Guide 3 Bush Fire & Environmental Protection Branch, 2010 5–10 tonnes per hectare scrub fuel 4 Fire & Emergency Services Authority of Western Australia 10–15 tonnes per hectare scrub fuel 6 © Fire & Emergency Services Authority of Western Australia 15–25 tonnes per hectare scrub fuel 9 480 Hay Street, Perth, 6000 25+ tonnes per hectare scrub fuel 13 ISBN 978-0-9806116-4-9 Leaf litter fuel 15 Glossary 16 Disclaimer The information contained in this publication is provided by the Fire and Emergency Services Authority (FESA) of Western Australia. This brochure has been prepared in good faith and is derived from sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of publication. Nevertheless, the reliability and accuracy of the information cannot be guaranteed and FESA expressly disclaims liability for any act or omission done or not done in reliance on the information and for any consequences, whether direct or indirect, arising from such act or omission. This publication is intended to be a guide only and readers should obtain their own independent advice and make their own necessary enquiries. Introduction Many factors infl uence fi re behaviour but none is more signifi cant than fuel. The availability, size, arrangement, moisture content and type of fl ammable material available all contribute to what can be considered as fuel. -

Reintroducing the Dingo: the Risk of Dingo Predation to Threatened Vertebrates of Western New South Wales

CSIRO PUBLISHING Wildlife Research http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/WR11128 Reintroducing the dingo: the risk of dingo predation to threatened vertebrates of western New South Wales B. L. Allen A,C and P. J. S. Fleming B AThe University of Queensland, School of Animal Studies, Gatton, Qld 4343, Australia. BVertebrate Pest Research Unit, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange Agricultural Institute, Forest Road, Orange, NSW 2800, Australia. CCorresponding author. Present address: Vertebrate Pest Research Unit, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Sulfide Street, Broken Hill, NSW 2880, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract Context. The reintroduction of dingoes into sheep-grazing areas south-east of the dingo barrier fence has been suggested as a mechanism to suppress fox and feral-cat impacts. Using the Western Division of New South Wales as a case study, Dickman et al. (2009) recently assessed the risk of fox and cat predation to extant threatened species and concluded that reintroducing dingoes into the area would have positive effects for most of the threatened vertebrates there, aiding their recovery through trophic cascade effects. However, they did not formally assess the risk of dingo predation to the same threatened species. Aims. To assess the risk of dingo predation to the extant and locally extinct threatened vertebrates of western New South Wales using methods amenable to comparison with Dickman et al. (2009). Methods. The predation-risk assessment method used in Dickman et al. (2009) for foxes and cats was applied here to dingoes, with minor modification to accommodate the dietary differences of dingoes. This method is based on six independent biological attributes, primarily reflective of potential vulnerability characteristics of the prey. -

To Name Those Lost: Assessing Extinction Likelihood in the Australian Vascular Flora J.L

To name those lost: assessing extinction likelihood in the Australian vascular flora J.L. SILCOCK, A.R. FIELD, N.G. WALSH and R.J. FENSHAM SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 1 Presumed extinct plant taxa in Australia that are considered taxonomically suspect, or whose occurrence in Australia is considered dubious. These require clarification, and their extinction likelihood is not assessed here. Taxa are sorted alphabetically by family, then species. No. of Species EPBC1 Last collections References and/or pers. (Family) (State)2 Notes on taxonomy or occurrence State Bioregion/s collected (populations) comms Trianthema cypseleoides Sydney (Aizoaceae) X (X) Known only from type collection; taxonomy needs to be resolved prior to targeted surveys being conducted NSW Basin 1839 1 (1) Steve Douglas Frankenia decurrens (Frankeniaceae) X (X) Very close to F.cinerea and F.brachyphylla; requires taxonomic work to determine if it is a good taxon WA Warren 1850 1 (1) Robinson & Coates (1995) Didymoglossum exiguum Also occurs in India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Malay Peninsula; known only from type collection in Australia by Domin; specimen exists, but Field & Renner (2019); Ashley (Hymenophyllaceae) X (X) can't rule out the possibility that Domin mislabelled some of these ferns from Bellenden Ker as they have never been found again. QLD Wet Tropics 1909 1 (1) Field Hymenophyllum lobbii Domin specimen in Prague; widespread in other countries; was apparently common and good precision record, so should have been Field & Renner (2019); Ashley (Hymenophyllaceae) X (X) refound by now if present QLD Wet Tropics 1909 1 (1) Field Avon Wheatbelt; Esperance Known from four collections between 1844 and 1892; in her unpublished conspectus of Hemigenia, Barbara Rye included H. -

Mammals of the Avon Region

Mammals of the Avon Region By Mandy Bamford, Rowan Inglis and Katie Watson Foreword by Dr. Tony Friend R N V E M E O N G T E O H F T W A E I S L T A E R R N A U S T 1 2 Contents Foreword 6 Introduction 8 Fauna conservation rankings 25 Species name Common name Family Status Page Tachyglossus aculeatus Short-beaked echidna Tachyglossidae not listed 28 Dasyurus geoffroii Chuditch Dasyuridae vulnerable 30 Phascogale calura Red-tailed phascogale Dasyuridae endangered 32 phascogale tapoatafa Brush-tailed phascogale Dasyuridae vulnerable 34 Ningaui yvonnae Southern ningaui Dasyuridae not listed 36 Antechinomys laniger Kultarr Dasyuridae not listed 38 Sminthopsis crassicaudata Fat-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 40 Sminthopsis dolichura Little long-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 42 Sminthopsis gilberti Gilbert’s dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 44 Sminthopsis granulipes White-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 46 Myrmecobius fasciatus Numbat Myrmecobiidae vulnerable 48 Chaeropus ecaudatus Pig-footed bandicoot Peramelinae presumed extinct 50 Isoodon obesulus Quenda Peramelinae priority 5 52 Species name Common name Family Status Page Perameles bougainville Western-barred bandicoot Peramelinae endangered 54 Macrotis lagotis Bilby Peramelinae vulnerable 56 Cercartetus concinnus Western pygmy possum Burramyidae not listed 58 Tarsipes rostratus Honey possum Tarsipedoidea not listed 60 Trichosurus vulpecula Common brushtail possum Phalangeridae not listed 62 Bettongia lesueur Burrowing bettong Potoroidae vulnerable 64 Potorous platyops Broad-faced -

Two New Legless Lizards from Eastern Australia (Reptilia: Squamata: Sauria: Pygopodidae)

Australasian Journal of Herpetology 3 Australasian Journal of Herpetology 30:3-6. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) Published 10 November 2015. ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) Two new legless lizards from Eastern Australia (Reptilia: Squamata: Sauria: Pygopodidae). RAYMOND T. HOSER 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: snakeman (at) snakeman.com.au Received 11 August 2015, Accepted 15 August 2015, Published 10 November September 2015. ABSTRACT Two new subspecies of legless lizards from south-eastern Australia within the genus Aprasia Gray, 1839 are formally identified and named according to the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Both are morphologically distinct from their nominate forms and both are allopatric in distribution with respect to the nominate forms. One of these populations, this being from Bendigo, Victoria and currently referred to as a population of Aprasia parapulchella, Kluge, 1974 has long been recognized as being taxonomically distinct from the nominate form (Osborne and Jones, 1995). The second taxon, referred to as being within Aprasia inaurita Kluge, 1974, was found to be distinct for the first time as part of this audit. Keywords: Taxonomy; nomenclature; Lizards; Aprasia; parapulchella; pseudopulchella; inaurita; new subspecies; gibbonsi; rentoni. INTRODUCTION MATERIALS, METHODS AND RESULTS As part of an audit of the reptiles in Victoria, Australia, two The audit consisted of looking at specimens from all relevant regionally isolated of legless lizards in the genus Aprasia Gray, species, herein effectively treated as two groups, namely A. 1839 were inspected with a view to assess their relationships inaurita and A.