Transport Infrastructure Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Labor Member in the Queensland Parliament

YOUR LABOR MEMBER IN THE QUEENSLAND PARLIAMENT Cape Vork / Douglas / Cooktown / Mareeba: Torres Strait / NPA P: 1800816264 - Fax: 07 40312437 P: 1800802391 - Fax: 07 4069 1620 PO Box 2080, Cairns 4870 PO Box 437, Thursday Island 4875 E: [email protected] E: cook.th [email protected] Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority Level 19 12 Creek Street BRISBANE QLD 4001 REVIEW OF SUN WATER PRICING STRUCTURE Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority by Jason O'Brien MP Member for Cook, on behalf of a constituent who is a Sun Water user, requesting changes to the pricing policy of Sun Water to their customers holding pension concession cards who access sun water for their domestic use only. Under the present Sun Water tariff structure they are able to negotiate how much revenue could be collected from variable and fixed charges. My submission is that Sun Water should be free to offer a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme for eligible pensions to reduce the impact of increased water price increases. This concession could be in the form of a rebate similar to the rate rebate scheme which applies across the state off local government rates charges. Sun Water must have the ability to provide water services to the community at a reasonable cost taking into account the most effective way to utilise the resource for the community's benefit. To this end pensions accessing Sun Water's resource purely for domestic use should be considered in a wider public interest context. Prices should be cost reflective and take into account relevant public interest matters such as pensioners accessing their resource In conclusion I submit that Sun Water should be providing a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme and the Queensland Competition Authority should recognise this as a public interest issue. -

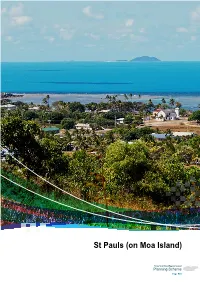

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

How Torres Strait Islanders Shaped Australia's Border

11 ‘ESSENTIALLY SEA‑GOING PEOPLE’1 How Torres Strait Islanders shaped Australia’s border Tim Rowse As an Opposition member of parliament in the 1950s and 1960s, Gough Whitlam took a keen interest in Australia’s responsibilities, under the United Nations’ mandate, to develop the Territory of Papua New Guinea until it became a self-determining nation. In a chapter titled ‘International Affairs’, Whitlam proudly recalled his government’s steps towards Papua New Guinea’s independence (declared and recognised on 16 September 1975).2 However, Australia’s relationship with Papua New Guinea in the 1970s could also have been discussed by Whitlam under the heading ‘Indigenous Affairs’ because from 1973 Torres Strait Islanders demanded (and were accorded) a voice in designing the border between Australia and Papua New Guinea. Whitlam’s framing of the border issue as ‘international’, to the neglect of its domestic Indigenous dimension, is an instance of history being written in what Tracey Banivanua- Mar has called an ‘imperial’ mode. Historians, she argues, should ask to what extent decolonisation was merely an ‘imperial’ project: did ‘decolonisation’ not also enable the mobilisation of Indigenous ‘peoples’ to become self-determining in their relationships with other Indigenous 1 H. C. Coombs to Minister for Aboriginal Affairs (Gordon Bryant), 11 April 1973, cited in Dexter, Pandora’s Box, 355. 2 Whitlam, The Whitlam Government, 4, 10, 26, 72, 115, 154, 738. 247 INDIGENOUS SELF-determinatiON IN AUSTRALIA peoples?3 This is what the Torres Strait Islanders did when they asserted their political interests during the negotiation of the Australia–Papua New Guinea border, though you will not learn this from Whitlam’s ‘imperial’ account. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Meriba Omasker Kaziw Kazipa (Torres Strait Islander Traditional Child Rearing Practice) Bill 2020

Parliamentary Meriba Omasker Kaziw Kazipa (Torres Strait Islander Traditional Child Rearing Practice) Bill 2020 - for our children's children Report No. 40, 56th Parliament Health, Communities, Disability Services and Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Committee August 2020 Health, Communities, Disability Services and Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Committee Chair Mr Aaron Harper MP, Member for Thuringowa Deputy Chair Mr Mark McArdle MP, Member for Caloundra Members Mr Martin Hunt MP, Member for Nicklin Mr Michael Berkman MP, Member for Maiwar Mr Barry O’Rourke MP, Member for Rockhampton Ms Joan Pease MP, Member for Lytton Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6626 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Technical Scrutiny +61 7 3553 6601 Secretariat Committee Web Page www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Health Acknowledgements The committee acknowledges the participation of Ms Cynthia Lui MP, Member for Cook at the regional hearings in Bamaga, Thursday Island and Saibai Island from 5 to 7 August 2020. The committee also acknowledges the assistance provided by the Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships and the Queensland Parliamentary Library. Images of woven mat provided with courtesy of, and consent from, Ms Isadora Akiba, Saibai Island, on 7 August 2020. Meriba Omasker Kaziw Kazipa (Torres Strait Islander Traditional Child Rearing Practice) Bill 2020 Contents Abbreviations iv Chair’s foreword v Recommendations vi 1 Introduction 1 Role of the committee 1 Inquiry process 2 1.2.1 Recognition -

Boigu Islands, Form the Northern Island Group of Torres Strait, Located Approximately 150 Km North of Thursday Island (See Figure 1)

PROFILE FOR MANAGEMENT OF THE HABITATS AND RELATED ECOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCE VALUES OF DAUAN ISLAND January 2013 Prepared by 3D Environmental for Torres Strait Regional Authority Land & Sea Management Unit Cover image: 3D Environmental (2013) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The granite rock pile that forms Dauan, along with nearby Saibai and Boigu Islands, form the Northern Island Group of Torres Strait, located approximately 150 km north of Thursday Island (see Figure 1). Whilst Saibai and Boigu Island are extensions of the alluvial Fly Platform, geologically part of the Papua New Guinea mainland, Dauan is formed on continental basement rock which extends northward from Cape York Peninsula to Mabadauan Hill on the south-west coast of Papua New Guinea. A total of 14 vegetation communities, within ten broad vegetation groups and 14 regional ecosystems are recognised on the island. The total known flora of comprises 402 species (14 ferns, 388 angiosperms), with 317 native and 85 naturalised species. Nine plant species are considered threatened at the commonwealth and state levels and a further 25 species considered to have significance at a regional level. As for the majority of Torres Strait Islands there is a lack of systematic survey of fauna habitats on the island. A desktop review identified 135 fauna species that are reported to occur on Dauan. This can be compared with the 384 terrestrial fauna species that have been reported for the broader Torres Strait Island group. The Dauan fauna comprises 20 reptiles, 100 birds, 3 frogs and 12 mammals. Of these, one reptile, one bird and four mammal species are introduced. -

Torres Strait Islanders: a New Deal

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS: A NEW DEAL A REPORT ON GREATER AUTONOMY FOR TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Affairs August 1997 Canberra Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISBN This document was produced from camera-ready copy prepared by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs and printed by AGPS Canberra. The cover was produced in the AGPS design studios. The graphic on the cover was developed from a photograph taken on Yorke/Masig Island during the Committee's visit in October 1996. CONTENTS FOREWORD ix TERMS OF REFERENCE xii MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE xiii GLOSSARY xiv SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS xv CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE.......................................................................................................................................1 CONDUCT OF THE INQUIRY ......................................................................................................................................1 SCOPE OF THE REPORT.............................................................................................................................................2 PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS .................................................................................................................................3 Commonwealth-State Cooperation ....................................................................................................................3 -

Card Operated Meter Information

Purchasing a power card for your card-operated meter Power cards are available from the following sales outlets: Community Retail Agent Address Arkai (Kubin) Community T.S.I.R.C. - Kubin KUBIN COMMUNITY, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Arkai (Kubin) Community CEQ - Kubin IKILGAU YABY RD, KUBIN VILLAGE, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Aurukun Island & Cape 39 KANG KANG RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Aurukun Supermarket Aurukun Kang Kang Café 502 KANG KAND RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Badu Hotel 199 NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Island & Cape Badu MAIRU ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Supermarket (Bottom Shop) Badu (Mulgrave) Island J & J Supermarket 341 CHAPMAN ST, BADU ISLAND QLD (Top Shop) 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Badu NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Bamaga Bamaga BP Service AIRPORT RD, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Station Bamaga Cape York Traders 201 LUI ST, BAMAGA QLD 4876 – Bamaga Store Bamaga CEQ – Bamaga 105 ADIDI AT, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island CEQ – Boigu TOBY ST, BOIGU QLD 4875 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Boigu 66 CHAMBERS ST, BOIGU ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) Daido Tavern PILOT ST, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) T.S.I.R.C. - Darnley COUNCIL OFFICE, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Dauan Island (Mt CEQ - Dauan MAIN ST, DAUAN ISLAND QLD 4875 Cornwallis) Supermarket Dauan Island (Mt T.S.I.R.C. - Dauan COUNCIL OFFICE, MAIN ST, DAUAN Cornwallis) ISLAND QLD 4875 Doomadgee CEQ – Doomadgee 266 GUNNALUNJA DR, DOOMADGEE QLD Supermarket 4830 Doomadgee Doomadgee 1 GOODEEDAWA RD, DOOMADGEE -

CAEPR DISCUSSION PAPERS Are Intended As a Forum for the Dissemination of Refereed Papers on Research That Falls Within the CAEPR Ambit

Coping with locational advantage: the economic development potential of tourism at Seisia community, Cape York Peninsula J.C. Altman No. 98/1995 ISSN 1036-1774 ISBN 0 7315 1772 5 SERIES NOTE The Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR) was established in March 1990 under an agreement between the Australian National University (ANU) and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC). CAEPR operates as an independent research unit within the University's Faculty of Arts and is funded by ATSIC, the Commonwealth Department of Social Security and the ANU. CAEPR's principal objectives are to undertake research to: • investigate the stimulation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander economic development and issues relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment and unemployment; • identify and analyse the factors affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in the labour force; and • assist in the development of government strategies aimed at raising the level of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in the labour market. The Director of the Centre is responsible to the Vice-Chancellor of the ANU and receives assistance in formulating the Centre's research agenda from an Advisory Committee consisting of five senior academics nominated by the Vice-Chancellor and four representatives nominated by ATSIC, the Department of Employment, Education and Training and the Department of Social Security. CAEPR DISCUSSION PAPERS are intended as a forum for the dissemination of refereed papers on research that falls within the CAEPR ambit. These papers are produced for discussion and comment within the research community and Aboriginal affairs policy arena. Many are subsequently published in academic journals. -

Part 7 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Sea Transport Safety The marine investigation unit of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) was contacted for information pertaining to recent accidents and incidents with large trading vessels in the region. The data provided related to five incidents that occurred after July 1995 and before 2004: a) A man overboard from the vessel Murshidabad in 1996; b) A close quarters situation between the Maersk Taupo and a small dive runabout off Ackers Shoal Beacon in 1997; c) The grounding of the vessel Thebes on Larpent Bank in 1997; d) The grounding of the vessel Dakshineshwar on Larpent Bank in 1997; and e) The grounding of the vessel NOL Amber on Larpent Bank in 1997. Figure 3.7 shows the location of marine accidents that have occurred in northern Queensland in 2004. Figure 3.7 Location of Marine Accidents in Northern Queensland (2004) Source: MSQ: 2005 Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 21 Figure 3.8 Existing Ferry Services Torres Strait Transport Ugar (Stephen) Island Infrastructure Plan Papua New Guinea Ferry Routes ° Saibai (Kaumag) Island Dauan Island Erub (Darnley) Island Map 1 - Saibai (Kaumag) Island to Dauan Island 1:200,000 Map 2 - Ugar (Stephen) Island to Erub (Darnley) Island 1:150,000 Hammond Waiben Map 1 Island (Thursday) Island Map 2 Nguruppai (Horn) Island Muralug (Prince of Wales) Island Map 3 Seisia Seisia Map 3 - Thursday Island 1:300,000 -

Badu Land and Sea Profile

Badu Land and Sea Profile RANGER GROUP Rangers 2015 MANAGEMENT PRIORITIES LAND • Native plants and animals • Burning• Land patrol • Weeds • Native nursery • Revegetation • Coastal management (beach patrol) OVERVIEW • Uninhabited island management Traditional island name Badu SEA • Crocodiles Western name Mulgrave • Turtle and dugong • Marine debris Western Islands Cluster Maluilgal Nation • Sea patrol • Seagrass Monitoring Local government TSIRC & TSC Registered Native Title Mura Badulgal (TSI) PEOPLE • Traditional ecological knowledge Body Corporate (RNTBC) Corporation RNTBC • Traditional and cultural sites • Community involvement Land type Continental Island • Visitor management Air distance from • Research support 49 Thursday Island (km) Area (ha) 10222 KEY VALUES Indicative max length (km) 11 CLIMATE CHANGE RISK Indicative max breadth (km) 13 Vulnerability to sea level rise (+1.0m) Very Low Max elevation (m) 190 Sea level rise response options Very High Healthy sea Marine water Coral reefs Seagrass Dugong Marine turtles Coastline length (km) 49 ecosystems quality meadows Population 783 (2011 ABS Census) Area of island zoned 162 development (ha) Subsistence Healthy land Sustainable Coasts Mangroves Coastal birds fishing ecosystems human settlements and beaches and wetlands Area of disturbed / 213 (2.1%) / undisturbed vegetation (ha/%) 10009 (97.9%) Supporting the Land and Sea Management Strategy for Torres Strait COMMUNITY OVERVIEW FUTURE SUSTAINABILITY INITIATIVES RECENT ACHIEVEMENTS Badu is a large (10,222ha) continental island in the The Badu community is highly reliant on air transport, Recent land and sea management achievements include: Near Western Cluster of the Torres Strait about diesel powered electricity generation and barge transport of supplies and materials to and from the community. 49km north of Thursday Island (Waiben). -

The Torres Strait Islands Collection at the Australian Museum

TECHNICAL REPORTS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM The Torres Strait Islands Collection at the Australian Museum Stan Florek 2005 dibi-dibi, breast ornament, Mer, AM E.17346 Florek • Torres Strait Islands Collection A M AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Technical Reports of the Australian Museum may be purchased at the Australian Museum Shop · www.amonline.net.au/shop/ or viewed online · www.amonline.net.au/publications/ Technical Reports of the Australian Museum Number 19 TECHNICAL REPORTS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Director: Frank Howarth The Australian Museum’s mission is to research, interpret, communicate and apply understanding of the environments The Editor: Shane F. McEvey and cultures of the Australian region to increase their long- term sustainability. The Museum has maintained the highest standards of scholarship in these fields for more Editorial Committee: than 175 years, and is one of Australia’s foremost publishers of original research in zoology, anthropology, Chair: G.D.F. Wilson (INVERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) archaeology, and geology. The Records of the Australian Museum (ISSN 0067- M.S. Moulds (INVERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) 1975) publishes the results of research on Australian S.F. McEvey (EX OFFICIO) Museum collections and of studies that relate in other ways J.M. Leis (VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) to the Museum’s mission. There is an emphasis on S. Ingleby (VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) Australasian, southwest Pacific and Indian Ocean research. I.T. Graham (GEOLOGY) The Records is released annually as three issues of one volume, volume 56 was published in 2004. Monographs D.J. Bickel (INVERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY) are published about once every two years as Records of V.J. Attenbrow (ANTHROPOLOGY) the Australian Museum, Supplements.