CO-CONSTRUCTING CRITICAL LITERACY in the MIDDLE SCHOOL CLASSROOM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinematic Specific Voice Over

CINEMATIC SPECIFIC PROMOS AT THE MOVIES BATES MOTEL BTS A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS CHOZEN S1 --- IN THEATER "TURN OFF CELL PHONE" MESSAGE FX NETWORKS E!: BELL MEDIA WHISTLER FILM FESTIVAL TRAILER BELL MEDIA AGENCY FALLING SKIES --- CLEAR GAZE TEASE TNT HOUSE OF LIES: HANDSHAKE :30 SHOWTIME VOICE OVER BEST VOICE OVER PERFORMANCE ALEXANDER SALAMAT FOR "GENERATIONS" & "BURNOUT" ESPN ANIMANIACS LAUNCH THE HUB NETWORK JUNE STUNT SPOT SHOWTIME LEADERSHIP CNN NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL SUMMER IMAGE "LIFE" SHAW MEDIA INC. Page 1 of 68 TELEVISION --- VIDEO PRESENTATION: CHANNEL PROMOTION GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT GENERIC :45 RED CARPET IMAGE FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY HAPPY DAYS FOX SPORTS MARKETING HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA MUCH: TMC --- SERENA RYDER BELL MEDIA AGENCY SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN COMPETITIVE CAMPAIGN DIRECTV DISCOVERY BRAND ANTHEM DISCOVERY, RADLEY, BIGSMACK FOX SPORTS 1 LAUNCH CAMPAIGN FOX SPORTS MARKETING LAUNCH CAMPAIGN PIVOT THE HUB NETWORK'S SUMMER CAMPAIGN THE HUB NETWORK ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT BRAG PHOTOBOOTH CBS TELEVISION NETWORK BRAND SPOT A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS Page 2 of 68 NBC 2013 SEASON NBCUNIVERSAL SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO ZTÉLÉ – HOSTS BELL MEDIA INC. ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN NICKELODEON HALLOWEEN IDS 2013 NICKELODEON HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA NICKELODEON KNIT HOLIDAY IDS 2013 NICKELODEON SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND CAMPAIGN BRAVO NICKELODEON SUMMER IDS 2013 NICKELODEON GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT --- LONG FORMAT "WE ARE IT" NUVOTV AN AMERICAN COACH IN LONDON NBC SPORTS AGENCY GENERIC: FBC COALITION SIZZLE (1:49) FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY PBS UPFRONT SIZZLE REEL PBS Page 3 of 68 WHAT THE FOX! FOX BROADCASTING CO. -

Tarzan (Na- “It’S Liketellingsomeone Who Crystal Cale, WHS Psychology One Infour American Teenagers “‘Smile, You’Llfeelbetter

Sports - Pages15-18 Prom - Pages 11-14 Feature -Pages 7-10 Editorial- Page 6 News -Pages1-5 wear anypants. he doesn’t because Finland from banned ics were Duck com- Donald In thecourseofanaver- Sunday willalwayshave PRSRT STD assorted insectsand10 Inside This apples, waspslikepine age lifetime,youwill, while sleeping,eat70 Months thatbeginona nuts, andwormslike Sweet Dreams U.S. Postage Paid a “Fridaythe13th.” Lucky Months Disney Dress Beetles tastelike That Really Ogden, UT Odds New Food Ends fried bacon. Issue Permit No. 208 Group spiders. Code Bugs! ‘n’ A cockroachcan A live several WEBER HIGHSCHOOL430WESTDRIVEPLEASANTVIEW,UT84414W head cut with its weeks off. THE thing that can be healed by sheer not some- does not,” sheadds. “It’s be healed, but beingupsetwhen it ken boneand notonlyexpectitto broke theirarmtonot haveabro- sion willjustgoaway.” theirdepres- they just‘cowboyup’ wanttobehappyorif people don’t is, andsotheythinkdepressed to-day problems,liketheirsadness just likeanormalresponsetoday- for peopletoassumedepressionis verycommon says,“It’s teacher, some misunderstandingsaboutit. sive episodes,yetthereseemstobe fromdepressionanddepres- suffer fromdepression. suffering pression is,”saysRose*,ajunior the facttheyhavenoideawhatde- say thesethingsitreallyhighlights Ithinkwhenpeople you nottobe.’ There isnoreasonfor to behappy. need You be sodownallthetime. ____________________________ Assistant totheChief By ____________________________ Teenagers seekbetterunderstandingofillness photo: Young Tarzan (Na- Tarzan photo: Young “It’s -

Academy Award-Winner Charlize Theron to Be Crowned with the Decade of Hotness Award at Spike TV's 'Guys Choice'

Academy Award-Winner Charlize Theron to Be Crowned With the Decade of Hotness Award at Spike TV's 'Guys Choice' Attendees Include Robert Downey, Jr., James Gandolfini, Scarlett Johansson, Jason Statham, Dwayne Johnson, Samuel L. Jackson, Kid Rock, Among Others Premieres Sunday, June 20th At 10 PM, ET/PT NEW YORK, May 25, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ --Spike TV's "Guys Choice" will honor Academy Award-winning actress Charlize Theron with the Decade of Hotness Award, one of the evenings highest honors, given to a legendary beauty we love for all of the right reasons: she kicks ass as a superhero, she's an Oscar winning actress and a world class beauty. Taping Saturday, June 5 at the Sony Pictures Studios in Culver City, CA, the fourth annual award show premieres Sunday, June 20 (10:00 PM - Midnight, ET/PT). (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20060322/NYW096LOGO) Theron's remarkable acting ability combined with her unbelievable beauty has earned her a legion of fans across the globe. For her extraordinary performance in "Monster," she won the Academy Award for Best Actress, Golden Globe Award for Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Picture and Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role. In 2007, men's magazine Esquire named Theron the Sexiest Woman Alive. Never afraid to mix it up, Spike guys find her equally appealing for her action roles in "Hancock," "The Italian Job" and "Reindeer Games." Last year's recipient was fellow Academy Award-winner, Halle Berry. -

Casey Patterson Named Senior Vice President, Event

CASEY PATTERSON NAMED SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, EVENT PRODUCTION AND TALENT DEVELOPMENT, SPIKE TV AND TV LAND New York, NY, March 31, 2008 -- Casey Patterson has been named senior vice president, event production and talent development, Spike TV and TV Land, it was announced jointly today by Doug Herzog, president, MTV Networks Entertainment Group and TV Land president, Larry W. Jones. Patterson, who most recently served as senior vice president of talent development and casting for Spike TV, will immediately be responsible for the creation and execution of brand-defining event programming and other talent-driven content for TV Land and Spike TV as well as oversee talent development for these two popular consumer brands within the MTV Networks Entertainment Group. In this newly-created position, Patterson is now responsible for fostering and overseeing Spike TV and TV Land’s relationships with major Hollywood film studios – in tandem with each network’s respective national ad sales and marketing teams – to offer partnership opportunities and oversee the formation of network tie-ins, custom programming events and other talent offerings as they relate to major film releases and other, high profile projects. Patterson will oversee all facets of the Spike TV and TV Land event production and talent development department, which previously was responsible solely for Spike TV. -more- Page 2: Casey Patterson “Casey’s leadership in creating distinctive and meaningful tent-pole events for Spike TV has been invaluable in strengthening the bond we have with our viewers, advertisers and the Hollywood community,” said Herzog. “She has proven to be a valuable member of the network’s executive team since its inception and we look forward to her bringing her wealth of knowledge and experience to TV Land in this expanded role within the MTV Networks Entertainment Group.” “Casey’s proven track record in event production and talent development makes her a natural choice to lead TV Land’s Hollywood agenda,” explains Jones. -

Information Extraction Over Structured Data: Question Answering with Freebase

Information Extraction over Structured Data: Question Answering with Freebase Xuchen Yao and Benjamin Van Durme “Who played in Gravity?” • Bing: Satori • Google: knowledge graph, Freebase 2 Answering from a Knowledge Base • the model challenge • the data challenge 3 QA from KB The Model Challenge 4 Previous Approach: Semantic Parsing 5 Previous Approach: Semantic Parsing dep parses ccg 6 Previous Approach: Semantic Parsing dep λ-DCS parses logic ccg first-order 7 Previous Approach: Semantic Parsing dep λ-DCS parses logic queries ccg first-order SPARQL SQL MQL ... 8 Previous Approach: Semantic Parsing dep λ-DCS parses logic queries ccg first-order SPARQL SQL MQL ... 9 Previous Approach: Semantic Parsing dep λ-DCS parses logic queries ccg first-order SPARQL SQL MQL ... 10 Is this how YOU find the answer? dep λ-DCS parses logic queries ccg first-order SPARQL SQL MQL ... 11 this instead might be how you find the answer Question: Who is the brother of Justin Bieber? who is the brother of Justin Bieber? 1st step: go to JB’s Freebase page 13 who is the brother of Justin Bieber? 2nd step: maybe wander around a bit? 14 who is the brother of Justin Bieber? finally: oh yeah, his brother 15 Freebase Topic Graph we know just enough about the answer from the following view: 16 Freebase Topic Graph who is the brother of Justin Bieber? 17 Signals! Major challenge for Question Answering: finding indicative (linguistic) signals for answers 18 Freebase Topic Graph who is the brother of Justin Bieber? who brother who who 19 QA on Freebase is now a binary classification problem on each node is answer? is answer? is answer? is answer ! 20 Features on Graph extract features for each node Justin Bieber Jazmyn Bieber Jaxon Bieber • has:awards_won • has:sibling • has:sibling • has:place_of_birth • gender:female • gender:male • has:sibling • type:person • type:person • type:person • … • … • … brown: relation; relations connect to other nodes blue: property; properties have literal values. -

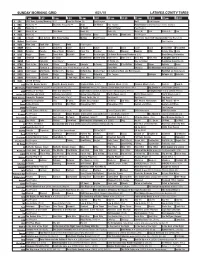

Sunday Morning Grid 6/21/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/21/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Paid Program 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News On Money Paid Program Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series: Daytona. 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Vista L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 2015 U.S. Open Golf Championship Final Round. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly A Knight’s Tale ›› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria 2015. -

Spike TV Bows Down to Legendary Funnyman Jim Carrey

Spike TV Bows Down to Legendary Funnyman Jim Carrey To Be Crowned Funniest M.F. At 2011 "Guys Choice" The Fifth Annual Event Premieres Friday, June 10 At 9 PM ET/PT NEW YORK, May 26, 2011 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Spike TV will present comedy icon Jim Carrey with the Funniest M.F. award at this year's "Guys Choice" bash. Funniest M.F. is one of the night's premiere honors as previous winners include fellow standouts Will Ferrell, Steve Carell and most recently, Chris Rock. Taping Saturday, June 4th at the Sony Pictures Studios in Culver City, CA, the fifth annual event premieres Friday, June 10 at 9:00 PM ET/PT. "When considering all the motherf***ers working today, we determined that Jim Carrey was by far the funniest of them all," said Casey Patterson, EVP, event production, talent and studio relations, Spike TV. "Jim Carrey is a comedic genius who has created some of the most iconic and indelible characters in film and TV. We're thrilled to be honoring him." Jim Carrey began his illustrious career in 1990 as a cast member on FOX's sketch comedy show, "In Living Color" where he shined brightest as accident-prone safety inspector Fire Marshall Bill and masculine female bodybuilder Vera de Milo. In 1994, Carrey was cast as the lead character in the hugely successful "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective," a role that launched him into stardom. Since then Carrey has won two Golden Globes, for his performances in "Man on the Moon" and "The Truman Show," and has starred in a countless number of memorable comedies including "Dumb and Dumber," "The Mask," "The Cable Guy," "Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls," "Me, Myself and Irene," "Bruce Almighty," "Liar Liar," "Yes Man," "I Love You Phillip Morris," among others. -

Walden Tells Jobs Foundation Economic

70 years Ago Today •Cherryville bats prevent WHS bid for ‘three-peat.’ June 6, 1944 •Cherryville cops opener D-Day with seventh-inning walk- off hit. The Invasion of Normandy Sports See page 1-B. ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Thursday Reporterfor the County of Columbus and her people. Monday, June 6, 2016 Second verdict Volume 125, Number 98 Whiteville, North Carolina sticks, Gore 75 Cents receives life nJuror who wavered after first ver- dict strong and forceful in her re- Inside sponses when individually polled as to her second verdict. 2-A By BOB HIGH •County to adopt Staff Writer budget; to ask to join state health plan at It took an extra 23 hours, but this time all 12 jurors individually confirmed by voice their tonight’s meeting. verdict that sent Ken- neth Harold Gore Jr., 3-A 32, to prison for life in •Cast of WCHS’s his first-degree murder ‘Annie’ experiences trial. No members of ‘humbling’ experi- Gore’s family attended ence at show’s finale. the session Thursday that ended at 11:10 a.m. Gore was passive again Thursday and didn’t Kenneth Gore look at the jurors as the courtroom clerk asked if the verdict the jury foreman returned was their verdict, and if it was still their decision. Each juror answered the questions with two quick “Yes” answers, including the woman who changed her mind Wednesday after an outburst of cursing and a tirade directly at Staff photo by FULLER ROYAL them by at least three members of Gore’s family. -

Swampscott Buildings Could House Town History a Dog, A

MONDAY, AUGUST 9, 2021 A dog, a squirrel, Swampscott and an ex-principal buildings By Allysha Dunnigan Former ITEM STAFF Lynn could house LYNN — The former principal of Washington Elemen- elementary tary School, Jeffrey Barile, published his rst children’s school town history book, titled “Dougie and Sammy: The Story of an Unlikely principal Friendship.” Jeffrey By Tréa Lavery The story discusses the friendship between a dog, Dou- Barile ITEM STAFF gie, and a squirrel, Sammy, and focuses on the bond made authored a between the two, despite their differences. children’s SWAMPSCOTT — An assessment Barile began writing the book a couple of years ago, in- book, “Dougie commissioned by the library, Historical spired by walks with his granddog Dougie. When he was and Sammy: Society and Historical Commission has walking the dog through the park one day, he said Dou- The Story of shown that the former police station gie kept barking at the squirrels running by. As a friendly An Unlikely building on Burrill Street would be the dog, Barile said he thought Dougie was just trying to talk Friendship.” best place for the town to store its his- toric documents and other materials. to and play with the squirrels. ITEM PHOTO | The assessment, which was paid for BARILE, A7 JAKOB MENENDEZ by a Library Services and Technolo- gy Act grant from the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners, eval- uated the 86 Burrill St. property, the Peabody library, Town Hall and the Humphrey House on Paradise Road. Those four buildings currently house the archives schools of the town, Historical Society and His- torical Commission. -

Goodfellas' Into the Guy Movie Hall of Fame Marking 20Th Anniversary

Spike TV's 'Guys Choice' to Induct Academy Award Winning 'GoodFellas' Into the Guy Movie Hall of Fame Marking 20th Anniversary Robert De Niro And Ray Liotta To Be Honored Premieres Sunday, June 20th At 10 PM, ET/PT NEW YORK, June 1, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ --Spike TV will induct quintessential mob classic and iconic movie "GoodFellas" into the Guy Movie Hall of Fame during the fourth annual "Guys Choice," taping Saturday, June 5 at the Sony Pictures Studios in Culver City, CA. Film stars Robert De Niro and Ray Liotta will reunite on stage to be honored, celebrating the 1990 cinematic masterpiece. This appearance at "Guys Choice" marks the first time the Hollywood heavyweights will come together to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the six time Academy Award-nominated "GoodFellas." The award will be presented by Emmy and Golden Globe winner James Gandolfini. "'GoodFellas' exploded into the culture, and with time we only appreciate it more. The film, the actors and the characters endure as part of one of the most important movies of all-time for our audience. I can't imagine anything our guys would like to see more than this reunion," says Guys Choice executive producer Casey Patterson. Based on the true-life best seller "Wiseguy" by Nicholas Pileggi, the film follows the rise and fall of a trio of gangsters from a blue-collar Italian section of Brooklyn, NY, Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro) and Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci),over the course of 30 years. "GoodFellas" is the fourth movie to earn this prestigious honor. -

Showfx Inc. a Portfolio

ShowFX Inc. A Portfolio © 2010 All Rights Reserved Show FX Inc. Britney Spears Circus Tour 2009 ShowFX created the custom VIP Ringside Seating, as well as all of the elaborate props, illusions and scenic elements for the show. Enhancing the Show Experience The custom ringside seats are constructed from aluminum tube frame and powder coated gold for a lasting appearance. They include gold anodized cup holders, !ame retardant cushions, and gold-leaf adorned Britney “B” crescent detailing. Each seat utilizes quick assembly mechanisms for daily build and strike, bene"ting concert goers and production crews alike. Britney’s Circus Props Circus Props, Flying Picture Frames, Tiger Cages, Magic Illusions, & Special E#ects, are all ShowFX contributions to the live tour. All equipment included custom carts designed to e$ciently pack all pieces to withstand the rigors of the road and maximize shipping space. From Sketches to The Stage David Mendoza ensures that the integrity of his initial designs are carried through to the "nal product while creating artistic yet functional pieces. The Britney Cage is fabricated from aluminum and "nished with a bright candy color coating giving it a yellow-gold depth that really pops under stage lights. Van Halen Tour 2004 ShowFX transformed world famous Rock & Roll architect Mark Fisher’s massive nuclear reactor design into a tour friendly concert set. The monolithic “reactor” was constructed from a welded aluminum structural frame, it was then covered with custom-molded "berglass panels. Hundreds of plastic rivet heads were added, and the piece was "nished with scenic paint to resemble weathered steel. -

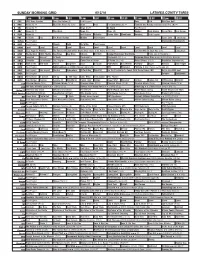

Sunday Morning Grid 6/12/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/12/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid F1 Countdown (N) Å Formula One Racing Canadian Grand Prix. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Underworld: Evolution (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Easy Yoga for Arthritis The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. (TVG) Eat Dirt With Dr. Josh Axe (TVG) Carpenters 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Louder Than Love: The Grande Pavlo Live in Kastoria Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Flashpoint Å Flashpoint (TV14) Å Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Baby Geniuses › (1999) Kathleen Turner.