"It's a Little Known Fact" That Copyright Law Is in Conflict with the Right of Publicity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

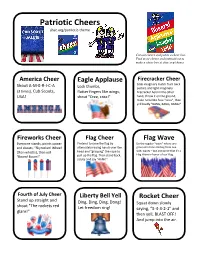

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Edmond Press

International Press International Sales Venice: wild bunch The PR Contact Ltd. Venice Phil Symes - Mobile: 347 643 1171 Vincent Maraval Ronaldo Mourao - Mobile: 347 643 0966 Tel: +336 11 91 23 93 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Fax: 041 5265277 Carole Baraton 62nd Mostra Venice Film Festival: Tel: +336 20 36 77 72 Hotel Villa Pannonia Email: [email protected] Via Doge D. Michiel 48 Gaël Nouaile 30126 Venezia Lido Tel: +336 21 23 04 72 Tel: 041 5260162 Email: [email protected] Fax: 041 5265277 Silva Simonutti London: Tel: +33 6 82 13 18 84 The PR Contact Ltd. Email: [email protected] 32 Newman Street London, W1T 1PU Paris: Tel: + 44 (0) 207 323 1200 Wild Bunch Fax: + 44 (0) 207 323 1070 99, rue de la Verrerie - 75004 Paris Email: [email protected] tel: + 33 1 53 01 50 20 fax: +33 1 53 01 50 49 www.wildbunch.biz French Press: French Distribution : Pan Européenne / Wild Bunch Michel Burstein / Bossa Nova Tel: +33 1 43 26 26 26 Fax: +33 1 43 26 26 36 High resolution images are available to download from 32 bd st germain - 75005 Paris the press section at www.wildbunch.biz [email protected] www.bossa-nova.info Synopsis Cast and Crew “You are not where you belong.” Edmond: William H. Macy Thus begins a brutal descent into a contemporary urban hell Glenna: Julia Stiles in David Mamet's savage black comedy, when his encounter B-Girl: Denise Richards with a fortune-teller leads businessman Edmond (William H. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library

DePaul Center for Urban Education Chicago Math Connections This project is funded by the Illinois Board of Higher Education through the Dwight D. Eisenhower Professional Development Program. Teaching/Learning Data Bank Useful information to connect math to science and social studies Topic: Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library Name Profession Nelson Algren author Joan Allen actor Gillian Anderson actor Lorenz Tate actor Kyle actor Ernie Banks, (former Chicago Cub) baseball Jennifer Beals actor Saul Bellow author Jim Belushi actor Marlon Brando actor Gwendolyn Brooks poet Dick Butkus football-Chicago Bear Harry Caray sports announcer Nat "King" Cole singer Da – Brat singer R – Kelly singer Crucial Conflict singers Twista singer Casper singer Suzanne Douglas Editor Carl Thomas singer Billy Corgan musician Cindy Crawford model Joan Cusack actor John Cusack actor Walt Disney animator Mike Ditka football-former Bear's Coach Theodore Dreiser author Roger Ebert film critic Dennis Farina actor Dennis Franz actor F. Gary Gray directory Bob Green sports writer Buddy Guy blues musician Daryl Hannah actor Anne Heche actor Ernest Hemingway author John Hughes director Jesse Jackson activist Helmut Jahn architect Michael Jordan basketball-Chicago Bulls Ray Kroc founder of McDonald's Irv Kupcinet newspaper columnist Ramsey Lewis jazz musician John Mahoney actor John Malkovich actor David Mamet playwright Joe Mantegna actor Marlee Matlin actor Jenny McCarthy TV personality Laurie Metcalf actor Dermot Muroney actor Bill Murray actor Bob Newhart -

Introducing the 10Th Annual Michigan Contractor of the Year (Mcoy) Nominees John Ratzenberger Our Top Sponsors

INTRODUCING THE 10TH ANNUAL MICHIGAN CONTRACTOR OF THE YEAR (MCOY) NOMINEES On October 17, 2019, the American Subcontractors Association of Michigan (ASAM) 2019 MCOY KEYNOTE SPEAKER: will be celebrating the 10th Annual MCOY Award Gala at Frederik Meijer Gardens & JOHN RATZENBERGER Sculpture Park. MCOY recognizes Michigan’s general contractors and construction managers with a track record of best practices, professionalism, and collaboration You may know John Ratzenberger from within the subcontracting community. Cheers, where he played the mailman, Cliff Clavin, or from his appearances in major films such as Superman and ASAM IS PLEASED TO ANNOUNCE THIS YEAR’S MCOY AWARD NOMINEES: The Empire Strikes Back. To a younger • The Christman Company • First Companies, Inc. generation, John is known as the only • Dan Vos Construction Company • Owen-Ames-Kimball Co. actor to voice a character in every Pixar • Elzinga & Volkers, Inc. • Pioneer Construction movie, including ‘Hamm the Pig’ in the • Erhardt Construction • Rockford Construction Toy Story franchise. John is an outspoken advocate for manufacturing and skilled ASAM members will vote to determine which of these nominees will take labor, working tirelessly to shine a light home the coveted award. Nominees will be scored on the following criteria: on the importance of manufacturing and trades, and working bid ethics & practices, safety, jobsite supervision, communication, schedule with legislators to bring back trades training in schools and build coordination, project relations, administrative procedures, payment terms, apprentice programs. and quality workmanship. For more information about ASAM and MCOY, please visit ASAMichigan.net. OUR TOP SPONSORS:. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

Christmas TV Schedule 2020

ChristmasTVSchedule.com’s Complete Christmas TV Schedule 2020 • All listings are Eastern time • Shows are Christmas themed, unless noted as Thanksgiving • Can’t-miss classics and 2020 Christmas movie premieres and are listed in BOLD • Listings are subject to change. We apologize for any inaccurate listings • Be sure to check https://christmastvschedule.com for the live, updated listing Sunday, November 8 5:00am – Family Matters (TBS) 5:00am – NCIS: New Orleans (Thanksgiving) (TNT) 6:00am – Once Upon a Holiday (2015, Briana Evigan, Paul Campbell) (Hallmark) 6:00am – A Christmas Miracle (2019, Tamera Mowry, Brooks Darnell) (Hallmark Movies) 7:00am – The Mistle-Tones (2012, Tori Spelling) (Freeform) 8:00am – 12 Gifts of Christmas (2015, Katrina Law, Aaron O’Connell) (Hallmark) 8:00am – Lucky Christmas (2011, Elizabeth Berkley, Jason Gray-Stanford) (Hallmark Movies) 9:00am – Prancer Returns (2001, John Corbett) (Freeform) 10:00am – A Christmas Detour (2015, Candace Cameron-Bure, Paul Greene) (Hallmark) 10:00am – The Christmas Train (2017, Dermont Mulroney, Kimberly Williams-Paisley) (Hallmark Movies) 10:00am – Sweet Mountain Christmas (2019, Megan Hilty, Marcus Rosner) (Lifetime) 12:00pm – Pride, Prejudice, and Mistletoe (2018, Lacey Chabert, Brendan Penny) (Hallmark) 12:00pm – Christmas in Montana (2019, Kellie Martin, Colin Ferguson) (Hallmark Movies) 12:00pm – Forever Christmas (2018, Chelsea Hobbs, Christopher Russell) (Lifetime) 2:00pm – Holiday Baking Championship (Thanksgiving) (Food) 2:00pm – Snow Bride (2013, Katrina Law, Patricia -

Millie. Off-Broadway, She Starred in a Coupla' White Chicks Sittin Around

‘OUR FIRST CHRISTMAS’ CAST BIOS DIXIE CARTER (Evie Baer) – Emmy ®-nominated actress Dixie Carter is one of America’s most beloved entertainers. A proud daughter of Tennessee, Carter has arguably created some of the most memorable strong Southern female characters in television history. Her celebrated portrayal of the daring design darling Julia Sugarbaker on the long-running hit series “Designing Women” made her instantly recognizable. The series also allowed the producers to showcase her formidable vocal talents, a gift she continues to share with her fans through sold-out concerts across the country. Carter has starred in no less than six television series, most recently as attorney Randi King on CBS’s “Family Law.” She is also a frequent guest-star on television’s most popular shows. In 2007, Carter received an Emmy ® Award nomination for her guest-starring role as Gloria Hodge on ABC’s “Desperate Housewives.” Carter is no stranger to the Great White Way, first gracing the Broadway stage in Sextet in 1974, followed by Pal Joey in 1976. More recent Broadway turns include her triumphant Maria Callas in Terrence McNally’s Master Class , for which she earned stellar reviews and consistently garnered standing ovations. Carter returned to Broadway to smashing success in 2004 as corrupt, funny landlady Mrs. Meers in the Tony Award-winning musical Thoroughly Modern Millie . Off-Broadway, she starred in A Coupla’ White Chicks Sittin Around Talkin’ and at the New York Public Theatre in Taken in Marriage, Fathers and Sons (Drama Desk Award) and Jesse and the Bandit Queen , for which she won a Theatre World Award. -

197 F.3D 1284 United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. George

197 F.3d 1284 United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. George WENDT, an individual; John Ratzenberger, an individual, Plaintiffs- Appellants, v. HOST INTERNATIONAL, INC., a Delaware corporation, Defendant-Appellee, and Paramount Pictures, Corporation, a Delaware corporation, Defendant-Intervenor. No. 96-55243. Dec. 28, 1999. Before: FLETCHER and TROTT, Circuit Judges, and JENKINS, [FN1] District Judge. FN1. Honorable Bruce S. Jenkins, Senior United States District Judge for the District of Utah, sitting by designation. Order; Dissent by Judge KOZINSKI. Prior Report: 125 F.3d 806 ORDER The panel has voted to deny the petition for rehearing. Judge Trott voted to reject the petition for rehearing en banc and Judges B. Fletcher and Jenkins so recommend. The full court was advised of the petition for rehearing en banc. An active Judge requested a vote on whether to rehear the matter en banc. The matter failed to receive a majority of the votes in favor of en banc consideration. Fed. R.App. P. 35. The petition for rehearing is denied and the petition for rehearing en banc is rejected. *1285 KOZINSKI, Circuit Judge, with whom Judges KLEINFELD and TASHIMA join, dissenting from the order rejecting the suggestion for rehearing en banc: Robots again. In White v. Samsung Elecs. Am., Inc., 971 F.2d 1395, 1399 (9th Cir.1992), we held that the right of publicity extends not just to the name, likeness, voice and signature of a famous person, but to anything at all that evokes that person's identity. The plaintiff there was Vanna White, Wheel of Fortune letter-turner extraordinaire; the offending robot stood next to a letter board, decked out in a blonde wig, Vanna-style gown and garish jewelry. -

On Behalf of the H Foundation, Thank You for Your Commitment to Finding a Cure for Cancer

On behalf of The H Foundation, thank you for your commitment to finding a cure for cancer. To help you make the most of your Goombay Bash, here is your “GOOMBAY GUIDE” with important details about the exciting evening we have planned for you. Tips for a Great Goombay Bash • CATCH THE CARIBBEAN SPIRIT: Wear your Hawaiian shirts, sundresses, shorts, and sandals! The Goombay Bash is a casual celebration so keep your tuxedos at home! • ARRIVE EARLY: Plan ahead! Traffic in Chicago can be VERY busy on a Saturday and can easily take 30 minutes or longer once close to the entrance at Lake Shore Drive. Doors open at 5:00pm! If you are driving to Navy Pier and security tells you the lot is full, tell them you are with the Goombay Bash and show them your parking placard. CLICK HERE to download! • VALET PARKING: Parking at Navy Pier always fills up and security will turn people away. We have arranged for reserved parking for Goombay attendees with valet service at a discounted rate of $33. Please tell security you are with the Goombay Bash and show them the PARKING PLACARD if they tell you the lot is full. • GUEST BUS: SOLD OUT! If you booked a spot on our luxury guest bus, no need to drive to attend the Goombay Bash! Here is what you need to know: o Departs: Our guest bus departs at 4:00 from Madison Street across from Cossitt School right behind Hortons. o Returns: The bus returns from Navy Pier after the Fireworks. -

Edmond / Norman 507 S

! EDMOND / NORMAN 507 S. Coltrane / 3203 Broce Dr. 341-2390 / 701-5999 www.CheersandMore.com Welcome to the Cheers and More All Star Cheerleading family. We are very proud of our highly successful, internationally recognized All Star Cheerleading program. This packet will provide you with the information you will need as parents of a Cheers and More All Star cheerleader. Please carefully read ALL of the important information contained in this packet. All Star Cheerleading is a serious and highly athletic team sport. The more you know, the better experience you and your child will have in this wonderful program. Cheers and More strives to insure that your child has every opportunity to learn cheerleading, achieve their goals, and have a great time, all while learning many important life lessons along the way. Many of the athletes we have trained have received college scholarships to continue cheering after high school. We rely on our All Star parents to help us build and maintain our family friendly, athlete centered atmosphere. All Star Squads Cheers and More All Stars are competitive cheerleaders participating in a serious team sport. Parental support of your children and his/her teams are an integral component to their success. We firmly believe that every athlete is a valuable and unique member of our program. Each child has a specific and unique contribution to his/her team that cannot be replaced. Our goal is to provide individual skill development for every child, not only in cheerleading, but in sportsmanship and teamwork as well. We will prepare our teams and athletes to perform to their individual and team best. -

Parent Communication Brochure

THE NEXT STEP IMPORTANT FACTS TO KEEP What can a parent do if the meeting with the IN MIND Vancouver coach did not provide a satisfactory resolution? 1. If an athlete visits a physician for an injury, he/she must bring a note from 1. Call and set-up an appointment the doctor before being allowed to School District with the athletic director to discuss return to practice. the situation. 2. Students who miss more than half a 2. At this meeting the appropriate day of classes are not eligible to par- next step can be determined as ticipate in that day’s practice or con- necessary. tests. Truancy will result in a suspen- ATHLETICS sion from the next scheduled contest. Whether or not this step is ever reached, please 3. Use of tobacco, drugs, or alcohol keep in mind the following protocol when you during the school year is a violation of elect to pursue a concern you have regarding Athletic Handbook rules and will result your son/daughter’s experience in one of our in an athletic suspension. Violations athletic programs. Please make contact as include actual use, possession and/or follows: sale, and con-structive possession as defined in the Athletic Handbook. 1. Head coach 4. Any athlete who is ejected from a 2. Athletic director contest will be suspended until after 3. Building principal the next contest at the same level is 4. District athletic coordinator completed. 5. Chief of secondary education 5. Athletes will be expected to maintain passing grades in 4 out of 5, 5 out of 6, Research indicates a student involved in co- or 6 out of 7 classes to be eligible to PARENT / COACH curricular activities has a greater chance for compete in contests.