Marketplace Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survivors Fight Pink Campaign

WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE The WEDNESDAY | OCTOBER Baylor12, 2011 * Lariatwww.baylorlariat.com SPORTS Page 6 NEWS Page 3 A&E Page 5 Most valuable player What’s on the inside Baylor style broadway Baylor defensive end Tevin Elliott’s Miss Plano Christine Tang looks to Baylor is well represented in 86-yard touchdown was the winning prove pageants are about more than The WaterTower Theatre showcase of moment in Saturday’s game looks at the Miss Texas competition ‘Spring Awakening,’ running until Oct. 23 Vol. 112 No. 25 © 2011, Baylor University In Print >> Clean sweep North Texas proved no Survivors fight pink campaign match for the Bears during By Kevin Begos Combo” at Jersey Mike’s Subs, or Tuesday’s game when Associated Press the Sephora Collection Pink Eye- Baylor defeated the Mean lash Curler. One year, there was Green in straight sets. The country is awash in pink for a pink bucket of Kentucky Fried Page 6 breast cancer awareness month and Chicken. some women are sick of it. The San Francisco group Breast While no one is questioning the Cancer Action has led the campaign >> Going green need to fight the deadly disease, to question pink products, but ex- A Baylor graduate was some breast cancer advocates are ecutive director Karuna Jaggar said among nine finalists starting to ask whether one of the they aren’t saying all such products most successful charity campaigns are bad. who spoke at a world in recent history has lost its focus. She said there’s no doubt that competition about her “The pink drives me nuts,” said when the pink ribbon campaigns patent-pending method Cynthia Ryan, an 18-year survivor started about 20 years ago there was for reducing the amount of breast cancer who also volun- still a great need to raise awareness. -

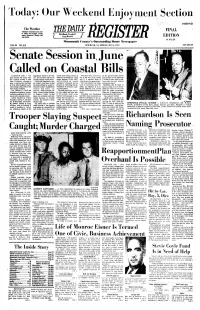

Senate Session In, June Called on Coastal Bills

Today: Our Weekend Enjoyment Section PAGES 9-12 The Weather Variable ciouoiness and cool- FINAL er today and tonight. Partly Red Bank, Freehold sunny tomorrow. Sunday fair and milder. Long Branch EDITION REGISTER 10 PAGES Monmouth County's Outstanding Home Newspaper VOL. 95 NO. 215 RED BANK,. N.JN.I. FRIDAY,. MAY 1.1971,19733 TEN CENTS 'iiiiiaiuiiinniiiiiiiiiiiiiiiniiiiuiiiiiiiiiuiiniinniiniiiiuiiinHiiiNiiuuiiiiiiiiiiiiiHiiiiiiniiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii i iiiiiiniiiiiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiin iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiitiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiitiiiiiniiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii i iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiitiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiniiiiiHiiiiiiintiimnil Senate Session in, June Called on Coastal Bills TRENTON (AP) - The Republican Party in the Sen- create state zoning control of The most votes received by for the special- Senate session State Senate will return here ate" for the three bills on the industrial development along any of the bills in the Senate had not been set but indicated for a special session in mid- second attempt to pass them. major portions of the coast, was VS. A measure needs 21 it would be some time in mid- June in another attempt to Cahiil said Democratic Sen- and establish an "ocean votes to pass the upper house. June after the state primary pass a controversial package ate leaders had been invited sanctuary," primarily for the After the Senate vote Kean election on June 5. of three bills designed to pro- but Senate Minority Leader J. purpose of controlling the de- said he believed that the Beadleston said he hoped to vide lasting safeguards for the Edward Crabiel of^Middlesex velopment of off-shore nucle- money and influence of oil in- have as many as 18 or 19 Re- , New Jersey coastline. County had been "in- ar power plants. -

The Public Eye, Spring 2008

The New Secular Fundamentalist Conspiracy!, p. 3 TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL RESEARCH PublicEye ASSOCIATES SPRING 2008 • Volume XXIII, No.1 $5.25 The North American Union Right-wing Populist Conspiracism Rebounds By Chip Berlet he same right-wing populist fears of Ta collectivist one-world government and new world order that fueled Cold War anticommunism, mobilized opposition to the Civil Rights Movement, and spawned the armed citizens militia movement in the 1990s, have resurfaced as an elaborate conspiracy theory about the alleged impending creation of a North American Union that would merge the United States, Canada, and Mexico.1 No such merger is seriously being con- templated by any of the three govern- ments. Yet a conspiracy theory about the North American Union (NAU) simmered in right-wing “Patriot Movement” alter- native media for several years before bub- bling up to reach larger audiences in the Ron Wurzer/Getty Images Wurzer/Getty Ron Dr. James Dobson, founder of the Christian Right group Focus on the Family, with the slogan of the moment. North American Union continues on page 11 IN THIS ISSUE Pushed to the Altar Commentary . 2 The Right-Wing Roots of Marriage Promotion The New Secular Fundamentalist Conspiracy! . 3 By Jean V. Hardisty especially welfare recipients, to marry. The fter the 2000 presidential campaign, I rationale was that marriage would cure their Reports in Review . 28 Afelt a shock of recognition when I read poverty. Wade Horn, appointed by Bush to that the George W. Bush Administration be in charge of welfare programs at the Now online planned to use its “faith-based” funding to Department of Health and Human Services www.publiceye.org . -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B. -

Discourses on Gender-Focused Aid in the Aftermath of Conflict

Afghanistan Gozargah: Discourses on Gender-Focused Aid in the Aftermath of Conflict Lina Abircfeh April 2008 PhD Candidate Student Number; 200320541 Development Studies Institute (DESTIN) London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) UMl Number: U613390 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Rjblishing UMI U613390 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. Ail rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code uesf ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Mi 48106 - 1346 F Library o» PoWicai '^ncUÊco»v K:*,j&eoG6_ certify that this is my original work. Lina Abircfeh April 2008 Abstract This research addresses gender-focused international aid in Afghanistan in the aftermath of conflict, focusing on the period of the Bonn Agreement (December 2001 - September 2005). The investigation begins with a contextualized understanding of women in Afghanistan to better understand their role in social transformations throughout history. This history is in some measure incompatible with the discourse on Afghan women that was created by aid institutions to justify aid interventions. Such a discourse denied Afghan women’s agency, abstracting them from their historical and social contexts. In so doing, space was created tor the proposed intervention using a discourse of transformation. -

News Briefs Mayor's Column

VOL. 113 - NO. 52 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, DECEMBER 25, 2009 $.30 A COPY A Very Merry Christmas THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO LUKE: 2:11-14 to our Readers and Advertisers (Submitted by Bob DeCristoforo) from the staff of the Post-Gazette Pam Donnaruma Claude Marsilia Ben Doherty Hilda Morrill Prof./Cav. Phillip J. DiNovo Freeway Mrs. Murphy Frances Fitzgerald Joan Smith Reinaldo Oliveira, Jr. Mary DiZazzo Bob Morello Ed Campochiaro Shallow Dom BarronRay David Trumbull Lee Porcella Bob SamanthaDeCristoforo Josephine (Photo by Bob DeCristoforo) Ed Turiello Bennett John Christoforo Molinari Yolanda The Birth of Jesus for all the people. Today in the town of David Sal Giarratani In those days Caesar Augustus issued a a Savior has been born to you; he is Christ Lisa Orazio Buttafuoco decree that a census should be taken of the the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will Richard Cappuccio Girard Plante Molinari entire Roman world. (This was the first cen- find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a Richard Preiss sus that took place while Quirinius was gov- manger.” Vita Sinopoli David Saliba Andre Urdi ernor of Syria.) And everyone went to his Suddenly a great company of the heavenly own town to register. host appeared with the angel, praising God So Joseph also went up from the town of and saying, Nazareth in Galilee to Judea, to Bethlehem “Glory to God in the highest, :and on earth the town of David, because he belonged to peace to men on whom his favor rests.” the house and line of David. -

View with Eight of Johnny’S Fans I’Ve Been Lucky Enough to See and Meet at Van Morrison’S Music but I Couldn’T Bear to Watch a Grumpy Sod Deliver the Music I His Gigs

TOUCH OUT Touch Out A collection of heartfelt anecdotes from Johnny Marr fans With much gratitude to all who contributed their heartfelt words to this book: Caroline Allen Marc McGarraghy Helen Angell Sue McMullen Contents Jade Bailey Dave Medley Chris Barry Valentina Miranda Steve Bates Lily Moayeri Foreword ............................................................................................................. 7 Chris Beattie Ali Molina By Marc McGarraghy Keniz Begum Alison Moore Lee Bellfield Snigdha Nag Part I: Reflections & Illuminations From The Johnny Marr Fandom .............. 11 Sarah Birch Lucija Naletilić Karen Black Ed Nash Part II: My Most Memorable Johnny Marr Moment ........................................ 51 Mel Blake Rachel Nesbitt Andy Campbell Jackie Nutty Part III: Tales Of Discovery .............................................................................. 91 Matthew Clow Siobhan O’Driscoll Nathan Curry Brian O’Grady Afterword ........................................................................................................125 Ash Custer Fiona ONeill By Aly Stevenson & Ory Englander Kari Da Emma Palor Hila Dagan Donka Petrova Laura Dean Lari Picker Lori DF Mariana Polizzi L.M. Linda Poulnott Elisabetta Melody Redhead Stephen Evans Marissa Rivera Gemma Faulkner Adam Roberts Walter Frith Mara Romanessi Kira L. Garcia Bernadette Rumsen Alex Harding Belinda Dillon Ryan Hogan Dave Jasper Mark Sharpley Alejandro Kapacevich Kirsty Smith Tom Kay Matthew Soper Amelia Kubota Craig Spence Fátima Kubota Ellen Aaron Symington Leerburger Caroline Nicola Westwood Leggott Karen Wheat Jill Lichtenstadter Chad Williams MJ Zander Foreword By Marc McGarraghy What is it that is so special about the relationship between Johnny Marr and his fans? I’ve often tried to put my finger on it from my unique vantage point, sandwiched between Johnny and the crowd. The intensity of the relationship between the two, how one feeds off the other, how one lifts the other and how the shared euphoria that builds through the gig is something very special to behold. -

Words Matter

ARKETPLACE OMMUNICATION M C WORDS MATTER A compilation of Merrie’s UPI columns. Every chapter offers sage, witty communications advice. COPYRIGHT The participant acknowledges that all ideas, concepts and models used in this manual are trade secrets of Spaeth Communications, Inc. and have been developed through the expenditure of substantial time, effort and creativity. The participant agrees that the system of ideas, concepts, and models will be held in confidence and will not be disclosed to anyone. The participant acknowledges that the graphic and written materials used in this manual are also trade secrets of Spaeth Communications, Inc. that have been developed through the expenditure of substantial time, effort and creativity. The participant agrees that the graphic and written materials will be held in confidence and will not be disclosed to anyone. The participant acknowledges that the graphic and written materials are copyrighted by Spaeth Communications. The participant agrees not to make copies of any of the copyrighted materials for any purpose whatsoever without the written consent of Spaeth Communications, Inc. ISBN-13: 978-1-59975-384-3 ISBN-10: 1-59975-384-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Articles 1. Middle East Peace Through Soap Operas: Palestinian students show how to promote peace…and the U.S. made it possible! 2. Speak Exxon Speak! Businesses need to take a leadership role and engage the public in discussions. 3. Stories as Proof: Missed the first lesson on learning to tell stories? Try again. 4. “As Prisons:” Words can liberate or enslave. Take unions. 5. Great Job! Is there someone empowered to tell the CEO he did a crummy job? 6. -

Copyrighted Material

1 “Reality” Is Splitting I n April 2004, a dozen men traveled from cities across the country to attend a clandestine meeting in a quaint, tucked- away corner of Dallas. The men were in their late fifties and early sixties, and they had about them a similar look: weathered yet tough. For more than thirty years, they had led divergent lives, but they were here to revisit their shared past—the crucible of Vietnam. John Kerry, the Massachusetts senator and decorated Vietnam veteran, had recently emerged as leader in the con- test for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. Like Kerry, the men in Dallas had once served on navy Swift boats, the shallow-water craft used in dangerous counterinsurgency missions aroundCOPYRIGHTED the Mekong Delta, in MATERIAL southeastern Vietnam, between 1968 and 1970. These men couldn’t stand the thought of their fellow vet becoming president. When they considered the manner in which Kerry, as a young man, had protested the 9 10 TRUE ENOUGH war, words like traitor and criminal came to mind. Now they hatched an audacious plan to undo Kerry’s reputation as a hero. Here’s the amazing thing: it worked. The men gathered in a grand two-story mansion that func- tions as the headquarters of Spaeth Communications, a public relations firm founded by a brilliant PR expert named Merrie Spaeth. Spaeth had agreed to host the meeting at the request of her old friend John O’Neill, the Swift boat veteran who rose to prominence in 1971, when he and Kerry debated the war in an appearance on The Dick Cavett Show. -

The Buried Life” Cast Members Made a To-Do List

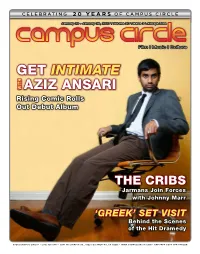

January 20 - January 26, 2010 \ Volume 20 \ Issue 3 \ Always Free Film | Music | Culture GET INTIMATE WITH AZIZ ANSARI Rising Comic Rolls Out Debut Album THE CRIBS Jarmans Join Forces with Johnny Marr ‘GREEK’ SET VISIT Behind the Scenes of the Hit Dramedy ©2010 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 988-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM • ONE FREE COPY PER PERSON FOR A GOOD TIME CALL CONTIKI 1.800.266.8454 GREEK ISLAND HOPPING \ 14 Days EUROPEAN DISCOVERY \ 14 Days Shop Trips at CONTIKI.COM OVER 190 ITINERARIES WORLDWIDE including Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Russia, Egypt, Southeast Asia and Mexico CST#1001728-20 2 Campus Circle 1.20.10 - 1.26.10 Join CAMPUS CIRCLE www.campuscircle.com campus circle INSIDE campus CIRCLE January 20 - January 26, 2010 Vol. 20 Issue 3 Editor-in-Chief Jessica Koslow 11 [email protected] Come Managing Editor Yuri Shimoda 8 12 [email protected] Film Editor 04 NEWS LOCAL NEWS Hang out Jessica Koslow [email protected] 06 FILM EXTRAORDINARY MEASURES Cover Designer Brendan Fraser and Harrison Ford join Sean Michael forces against an incurable disorder. with us! Editorial Interns Melissa Russell, Marvin G. Vasquez 06 FILM PROJECTIONS 07 FILM LEE STRASBERG INSTITUTE Contributing Writers Celebrating 40 Years in Theatre and Film Geoffrey Altrocchi, Jonathan Bautts, Scott Bedno, China Bialos, Erica Carter, Richard 07 FILM REVIEWS Castaneda, Joshua Chilton, Natasha Desianto, James Famera, Denise Guerra, Andrew 08 FILM AZIZ ANSARI Herrold, Zach Hines, Damon Huss, Jonathan Knell, Becca Lett, Lucia, Ebony March, Angela Hilarious star on the rise unveils debut Matano, Stephanie Nolasco, Samantha Ofole, comedy CD and DVD. -

Stanley Clarke About the Swiffer and Charms Other Stories

The e-journal of analog and digital sound. no.26 2009 The POWER Issue MONSTER MONOBLOCKS! McIntosh MC 1.2KW Simaudio Moon W-7M Power and Finesse: Burmester 911 MK.3 darTZeel’s CTH-8550 Massive Bass: JL Audio’s Mighty Gotham World’s First Review! The Rega Osiris Amplifier Factory Visits: Bang & Olufsen and Nagra Jaan Uhelszki talks to Mark Mothersbaugh Stanley Clarke about the Swiffer and charms other stories. Portland with Chick Corea and Lenny White TONE A 1 NO.26 2 0 0 9 PUBLISHER Jeff Dorgay EDITOR Bob Golfen ART DIRECTOR Jean Dorgay r MUSIC EDITOR Ben Fong-Torres ASSISTANT Bob Gendron MUSIC EDITOR M USIC VISIONARY Terry Currier STYLE EDITOR Scott Tetzlaff C O N T R I B U T I N G Bailey S. Barnard WRITERS Tom Caselli Kurt Doslu Anne Farnsworth Joe Golfen Jesse Hamlin Rich Kent Ken Kessler Rick Moore Jerold O’Brien Michele Rundgren Todd Sageser Richard Simmons Jaan Uhelszki Randy Wells UBER CARTOONIST Liza Donnelly ADVERTISING Jeff Dorgay WEBSITE bloodymonster.com Cover Photo: Stanley Clark by Jeff Dorgay tonepublications.com Editor Questions and Comments: [email protected] 800.432.4569 © 2009 Tone MAGAZIne, LLC All rights reserved. TONE A 2 NO.26 2 0 0 9 7. PUBLISHER’S LETTER 8. TONE TOON By Liza Donnelly features Old School: 9 The Mark Levinson no.23 By Jerold O’Brien Almost everything you want to 1 8 know about Mark Mothersbaugh By Jaan Uhelszki Rolling with the Stones 36 By Ben Fong-Torres 68 Dealers That Mean Business: 45 A Visit to TomTom Audio in St. -

GENE HOGLAN to Those Who Aspire to a Drumming Career Filled with Heroic Performances and Boundless Creativity, the Atomic Clock’S Reign Has Long Been Indisputable

!N)NCREDIBLE0RIZE 0ACKAGE&ROM2OLAND *%&&"%#+3.!2!$!-)#(!%,7!,$%.s-!44#!-%2/. 7). 6ALUED!T/VER .OVEMBER 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 0/24./9 /.4(%.%7 !6%.'%$ 3%6%.&/,$()35,4)-!4%2%642)"54% '!2)"!,$) 0!44%2.34/ )-02/6% 9/5202%#)3)/. !15),%3 '%.% 02)%34%2 *5344294/+%%050 $!25*/.%3 (/',!.-%4!,(%2/7)4( 3/5, (/0/2)').!, !4(/53!.$&!#%3 2%6)%7%$ -/$%2.$25--%2#/- 4!-!350%234!2")2#(452+)3(6).4!'%3/5,32%-/!-"!33!$/284!44//32/,!.$30$ Volume 34, Number 11 • Cover photo by Gemini Visuals CONTENTS 44 30 DARU JONES He lays down cutting-edge live and programmed beats Paul La Raia with Talib Kweli and Mos Def and on his own prolific productions—not only breaking tradition, but bringing a whole new approach to the game. 38 AQUILES PRIESTER Think there’s nothing new under the sun in metal drumming? Well, get in the double bass shed, because Hangar’s drummer has something to say about that. 44 GENE HOGLAN To those who aspire to a drumming career filled with heroic performances and boundless creativity, the Atomic Clock’s reign has long been indisputable. 16 UPDATE Jeff Beck’s NARADA MICHAEL WALDEN Ex-Scorpion HERMAN “THE GERMAN” RAREBELL 38 30 20 GIMME 10! Trans Am’s SEBASTIAN THOMSON Paul La Raia Ricardo Zupa 58 A DIFFERENT VIEW DEVIN TOWNSEND 66 IN THE STUDIO MIKE PORTNOY With Avenged Sevenfold 74 PORTRAITS Christian McBride/Kurt Elling’s ULYSSES OWENS JR. The Cribs’ ROSS JARMAN 98 78 78 WOODSHED Rick Malkin Nashville Session Drummer NICK BUDA 90 REASONS TO LOVE Pearl Jam/Soundgarden’s MATT CAMERON 98 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT...? ARMEN HALBURIAN MD DIGITAL SUBSCRIBERS! When you see this icon, click on a shaded box on the page to open the audio player.