General Information About BBO Robots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Things You Might Like to Know About Duplicate Bridge

♠♥♦♣ THINGS YOU MIGHT LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT DUPLICATE BRIDGE Prepared by MayHem Published by the UNIT 241 Board of Directors ♠♥♦♣ Welcome to Duplicate Bridge and the ACBL This booklet has been designed to serve as a reference tool for miscellaneous information about duplicate bridge and its governing organization, the ACBL. It is intended for the newer or less than seasoned duplicate bridge players. Most of these things that follow, while not perfectly obvious to new players, are old hat to experienced tournaments players. Table of Contents Part 1. Expected In-behavior (or things you need to know).........................3 Part 2. Alerts and Announcements (learn to live with them....we have!)................................................4 Part 3. Types of Regular Events a. Stratified Games (Pairs and Teams)..............................................12 b. IMP Pairs (Pairs)...........................................................................13 c. Bracketed KO’s (Teams)...............................................................15 d. Swiss Teams and BAM Teams (Teams).......................................16 e. Continuous Pairs (Side Games)......................................................17 f. Strategy: IMPs vs Matchpoints......................................................18 Part 4. Special ACBL-Wide Events (they cost more!)................................20 Part 5. Glossary of Terms (from the ACBL website)..................................25 Part 6. FAQ (with answers hopefully).........................................................40 Copyright © 2004 MayHem 2 Part 1. Expected In-Behavior Just as all kinds of competitive-type endeavors have their expected in- behavior, so does duplicate bridge. One important thing to keep in mind is that this is a competitive adventure.....as opposed to the social outing that you may be used to at your rubber bridge games. Now that is not to say that you can=t be sociable at the duplicate table. Of course you can.....and should.....just don=t carry it to extreme by talking during the auction or play. -

Tt Fall 12 Web.Pub

VOL. 53 No. 3 FALL 2012 Meet Michigan’s winning mini-Spingold squad Editor’s note: A team of five 20-something Ann Arbor players won the 0-1500 mini- Spingold KO, a multi- day limited national championship, at the summer North Ameri- can Bridge Champion- ships in Philadelphia. A month earlier, they also won the Sunday Winners of the mini-Spingold 0-1500 Swiss Teams at the KO Teams: (front) Jin Hu and Jonathan Fleischmann; (back) Max Glick, Zach- Toledo Regional. ary Scherr and Zachary Wasserman. Here are their stories: Jonathan Fleischmann ter. I'm an attorney less than a year out of law school. I'm 24 years old and live in I started playing in 1999 Bloomfield Hills with my fa- (Continued on page 22) ther, two brothers, and a sis- DON’T FORGET TO VOTE The annual election for MBA Board of Directors will be held during the last four days of the October regional. If you cannot be there on one of those days, you can still vote by complet- ing and sending in an absentee ballot. See page 5. Candi- dates’ pictures and statements appear on pages 6 and 7. Michigan Bridge Association Unit #137 2012 VINCE & JOAN REMEY MOTOR CITY REGIONAL October 8-14, 2012 Site: William Costick Center, 28600 Eleven Mile Road, Farmington Hills MI 48336 (between Inkster and Middlebelt roads) 248-473-1816 Intermediate/Newcomers Schedule (0-299 MP) Single-session Stratified Open Pairs: Tue. through Fri., 1 p.m. & 7 p.m.; Sat., 10 a.m. & 2:30 p.m. -

Bridge Glossary

Bridge Glossary Above the line In rubber bridge points recorded above a horizontal line on the score-pad. These are extra points, beyond those for tricks bid and made, awarded for holding honour cards in trumps, bonuses for scoring game or slam, for winning a rubber, for overtricks on the declaring side and for under-tricks on the defending side, and for fulfilling doubled or redoubled contracts. ACOL/Acol A bidding system commonly played in the UK. Active An approach to defending a hand that emphasizes quickly setting up winners and taking tricks. See Passive Advance cue bid The cue bid of a first round control that occurs before a partnership has agreed on a suit. Advance sacrifice A sacrifice bid made before the opponents have had an opportunity to determine their optimum contract. For example: 1♦ - 1♠ - Dbl - 5♠. Adverse When you are vulnerable and opponents non-vulnerable. Also called "unfavourable vulnerability vulnerability." Agreement An understanding between partners as to the meaning of a particular bid or defensive play. Alert A method of informing the opponents that partner's bid carries a meaning that they might not expect; alerts are regulated by sponsoring organizations such as EBU, and by individual clubs or organisers of events. Any method of alerting may be authorised including saying "Alert", displaying an Alert card from a bidding box or 'knocking' on the table. Announcement An explanatory statement made by the partner of the player who has just made a bid that is based on a partnership understanding. The purpose of an announcement is similar to that of an Alert. -

SEVERANCE © Mr Bridge ( 01483 489961

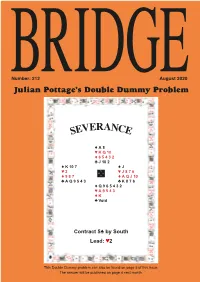

Number: 212 August 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem VER ANCE SE ♠ A 8 ♥ K Q 10 ♦ 6 5 4 3 2 ♣ J 10 2 ♠ K 10 7 ♠ J ♥ N ♥ 2 W E J 8 7 6 ♦ 9 8 7 S ♦ A Q J 10 ♣ A Q 9 5 4 3 ♣ K 8 7 6 ♠ Q 9 6 5 4 3 2 ♥ A 9 5 4 3 ♦ K ♣ Void Contract 5♠ by South Lead: ♥2 This Double Dummy problem can also be found on page 5 of this issue. The answer will be published on page 4 next month. of the audiences shown in immediately to keep my Bernard’s DVDs would put account safe. Of course that READERS’ their composition at 70% leads straight away to the female. When Bernard puts question: if I change my another bidding quiz up on Mr Bridge password now, the screen in his YouTube what is to stop whoever session, the storm of answers originally hacked into LETTERS which suddenly hits the chat the website from doing stream comes mostly from so again and stealing DOUBLE DOSE: Part One gives the impression that women. There is nothing my new password? In recent weeks, some fans of subscriptions are expected wrong in having a retinue. More importantly, why Bernard Magee have taken to be as much charitable The number of occasions haven’t users been an enormous leap of faith. as they are commercial. in these sessions when warned of this data They have signed up for a By comparison, Andrew Bernard has resorted to his breach by Mr Bridge? website with very little idea Robson’s website charges expression “Partner, I’m I should add that I have of what it will look like, at £7.99 plus VAT per month — excited” has been thankfully 160 passwords according a ‘founder member’s’ rate that’s £9.59 in total — once small. -

Teamwork Exercises and Technological Problem Solving By

Teamwork Exercises and Technological Problem Solving with First-Year Engineering Students: An Experimental Study Mark R. Springston Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Curriculum and Instruction Dr. Mark E. Sanders, Chair Dr. Cecile D. Cachaper Dr. Richard M. Goff Dr. Susan G. Magliaro Dr. Tom M. Sherman July 28th, 2005 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Technology Education, Engineering Design Activity, Teams, Teamwork, Technological Problem Solving, and Educational Software © 2005, Mark R. Springston Teamwork Exercises and Technological Problem Solving with First-Year Engineering Students: An Experimental Study by Mark R. Springston Technology Education Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University ABSTRACT An experiment was conducted investigating the utility of teamwork exercises and problem structure for promoting technological problem solving in a student team context. The teamwork exercises were designed for participants to experience a high level of psychomotor coordination and cooperation with their teammates. The problem structure treatment was designed based on small group research findings on brainstorming, information processing, and problem formulation. First-year college engineering students (N = 294) were randomly assigned to three levels of team size (2, 3, or 4 members) and two treatment conditions: teamwork exercises and problem structure (N = 99 teams). In addition, the study included three non- manipulated, independent variables: team gender, team temperament, and team teamwork orientation. Teams were measured on technological problem solving through two conceptually related technological tasks or engineering design activities: a computer bridge task and a truss model task. The computer bridge score and the number of computer bridge design iterations, both within subjects factors (time), were recorded in pairs over four 30-minute intervals. -

A Gold-Colored Rose

Co-ordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer – Editor: Brent Manley – Assistant Editors: Mark Horton, Brian Senior & Franco Broccoli – Layout Editor: Akis Kanaris – Photographer: Ron Tacchi Issue No. 13 Thursday, 22 June 2006 A Gold-Colored Rose VuGraph Programme Teatro Verdi 10.30 Open Pairs Final 1 15.45 Open Pairs Final 2 TODAY’S PROGRAMME Open and Women’s Pairs (Final) 10.30 Session 1 15.45 Session 2 Rosenblum winners: the Rose Meltzer team IMP Pairs 10.30 Final A, Final B - Session 1 In 2001, Geir Helgemo and Tor Helness were on the Nor- 15.45 Final A, Final B - Session 2 wegian team that lost to Rose Meltzer's squad in the Bermu- Senior Pairs da Bowl. In Verona, they joined Meltzer, Kyle Larsen,Alan Son- 10.30 Session 5 tag and Roger Bates to earn their first world championship – 15.45 Session 6 the Rosenblum Cup. It wasn't easy, as the valiant team captained by Christal Hen- ner-Welland team mounted a comeback toward the end of Contents the 64-board match that had Meltzer partisans worried.The rally fizzled out, however, and Meltzer won handily, 179-133. Results . 2-6 The bronze medal went to Yadlin, 69-65 winners over Why University Bridge? . .7 Welland in the play-off. Left out of yesterday's report were Osservatorio . .8 the McConnell bronze medallists – Katt-Bridge, 70-67 win- Championship Diary . .9 ners over China Global Times. Comeback Time . .10 As the tournament nears its conclusion, the pairs events are The Playing World Represented by Precious Cartier Jewels . -

System Notes

System Notes James Sundstrom Nathan Savir April 9, 2009 Notation Legend M Either Major. If used multiple times, it always refers to the same major. For example, 1M-2| -2M means either the auction 1~ -2| - 2~ or 1♠ -2| -2♠ , no other auction. m Either minor. As per M. OM Other major. This is only used after 'M', such as 1m-1M-2NT-3OM. om Other minor. As per OM. R Raise. Used in some of the step based system to mean a simple raise, such as 1~ -2~ . DR Double Raise. Q Cuebid. Acknowledgements Special thanks are owed to Blair Seidler, without whose teaching I probably would not ever have written these notes. If I did write them, they surely would not be nearly as good as they are. These notes are a (mostly very-distant) relative of his Carnage notes, though a few sections have been borrowed directly from Carnage. 1 Contents I Non-Competitive Auctions4 1 Opening Bid Summary6 2 Minor Suit Auctions7 2.1 Minor-Major................................7 2.1.1 Suit Bypassing Agreements...................7 2.1.2 New Minor Forcing........................7 2.1.3 Reverses..............................8 2.2 Minor Oriented Auctions.........................8 2.3 NT Oriented auctions...........................8 2.4 Passed Hand Bidding...........................8 3 Major Suit Auctions9 3.1 1 over 1 Auctions.............................9 3.2 Major Suit Raise Structure........................9 3.2.1 Direct Raises...........................9 3.2.2 Bergen...............................9 3.2.3 Jacoby 2NT............................9 3.2.4 3NT................................ 10 3.2.5 Splinters.............................. 10 3.3 Passed Hand................................ 10 3.3.1 Drury.............................. -

2000 Bridge Bulletin Index

2000 Bridge Bulletin Index ACBL BRIDGE HALL OF FAME. George Rosenkranz named Blackwood Award winner, Meyer Schleifer receives the von Zedtwitz Award C February. Hall of Fame inducts Lou Bluhm, Harry Fishbein, Charles Solomon, George Rosenkranz, Sidney Lazard, Meyer Schleifer and Ira Rubin C October. ACBL BOARD OF DIRECTORS. Highlights from the Boston Board meeting --- February. Election notice C March C May . Highlights of Cincinnati Board meeting C May. Highlights from the Anaheim meeting C October. Election results for 2000 Board C November. ACBL CHARITY FOUNDATION. 2000 Charity Committee appointees named --- February. ACBL CHARITY GAME. Winners C August. ACBL GOODWILL COMMITTEE. 2000 Appointees named --- February. ACBL HALL OF FAME. Rosenkranz wins Blackwood award; Meyer Schleifer is von Zedtwitz award winner C February. ACBL HONORARY MEMBER OF THE YEAR. Chip Martel named for 2000 --- February. ACBL INSTANT MATCHPOINT GAME. Promo C August, September. Results C December. ACBL INTERNATIONAL FUND GAME. Winners C July, November. ACBL PATRON MEMBER LIST. December. ACBL SENIOR GAME. Winners C May. ACE OF CLUBS. Winners of the 1999 contest --- April. AMERICAN BRIDGE ASSOCIATION. Schedule of upcoming national events --- monthly. ANAHEIM NABC. Promos C April --- July. Meltzer squad wins Spingold; Wei-Sender team takes Wagar; District 9 repeats win in GNT-A; District 19 wins GNT-B title; District 13 victorious in GNT-C contest; Zia, Rosenberg top LM Pairs field; Ping, Leung win Red Ribbon; Nugit squad wins Senior Swiss teams C October. Willenken, Silverstein win Fast Open Pairs; Bach and Burgess take IMP Pairs title; Mixed B-A-M winners; 199er Pairs winners; Five-way tie fir Fishbein Trophy; other NABC highlights C November. -

Post Mortem Secretary: Mary Paulone Carns Treasurer: John Alioto Associates: Phyllis Geinzer……

Editor: Arlene Port 220 N Dithridge #404 Unit 142 ` Pittsburgh, PA April, 2021 WEBSITE AT www.pittsburghbridge.org Pgh.PA. 15213 c President: Chris Wang Tel: 412-521-3637 [email protected] Vice President: Craig Biddle Post mortem Secretary: Mary Paulone Carns Treasurer: John Alioto Associates: Phyllis Geinzer……. Memoriam Club Manager: Mary Carns Chris Wang………...First At The Post Unit Recorder: Judi Soon ([email protected]) All the news that fits in print BRIDGE BYTES ……….by arlene port ………..By Ernie Retetagos The very good news is that almost all of those people at a certain BIDDING SYSTEMS age (which I won’t mention) have received one or both of their vaccine shots. This is very good news because most of our peer group in the bridge The bidding systems that we use today are the product of decades of evolu- world is of that certain age. I won’t mention it. We You know who we tion. The early days of contract bridge featured the Ely Culbertson method of hand are. evaluation. The strength for an opening bid was determined by honor tricks, or what Also very good news is that bridge, while not at the present time, we call quick tricks. Charles Goren later popularized the 4-3-2-1 high card point will be restored to our face-to-face games sooner than later. The ACBL has count method for opening bids. This forerunner of Standard American bidding also continued to have their nationally ranked games virtually, so if you’re look- added points for distribution, one for a doubleton, two for a singleton. -

CONTEMPORARY BIDDING SERIES Section 1 - Fridays at 9:00 AM Section 2 – Mondays at 4:00 PM Each Session Is Approximately 90 Minutes in Length

CONTEMPORARY BIDDING SERIES Section 1 - Fridays at 9:00 AM Section 2 – Mondays at 4:00 PM Each session is approximately 90 minutes in length Understanding Contemporary Bidding (12 weeks) Background Bidding as Language Recognizing Your Philosophy and Your Style Captaincy Considering the Type of Scoring Basic Hand Evaluation and Recognizing Situations Underlying Concepts Offensive and Defensive Hands Bidding with a Passed Partner Bidding in the Real World Vulnerability Considerations Cue Bids and Doubles as Questions Free Bids Searching for Stoppers What Bids Show Stoppers and What Bids Ask? Notrump Openings: Beyond Simple Stayman Determining When (and Why) to Open Notrump When to use Stayman and When to Avoid "Garbage" Stayman Crawling Stayman Puppet Stayman Smolen Gambling 3NT What, When, How Notrump Openings: Beyond Basic Transfers Jacoby Transfer Accepting the transfer Without interference Super-acceptance After interference After you transfer Showing extra trumps Second suit Splinter Texas Transfer: When and Why? Reverses Opener’s Reverse Expected Values and Shape The “High Level” Reverse Responder’s Options Lebensohl Responder’s Reverse Expected Values and Shape Opener’s Options Common Low Level Doubles Takeout Doubles Responding to Partner’s Takeout Double Negative Doubles When and Why? Continuing Sequences More Low Level Doubles Responsive Doubles Support Doubles When to Suppress Support Doubles of Pre-Emptive Bids “Stolen Bid” or “Shadow” Doubles Balancing Why Balance? How to Balance When to Balance (and When Not) Minor Suit Openings -

The Perceptions of Policymakers on the Transfer Pathway in Texas Public

THE PERCEPTIONS OF POLICYMAKERS ON THE TRANSFER PATHWAY IN TEXAS PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION Kimberly A. Faris Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2016 APPROVED: Amy Fann, Major Professor Beverly Bower, Committee Member Marc Cutright, Committee Member Celia Williamson, Committee Member Daniel Chen, Program Coordinator for Higher Education Jan Holden, Chair of the Department of Counseling and Higher Education Jerry Thomas, Dean of the College of Education Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Faris, Kimberly. The Perceptions of Policymakers on the Transfer Pathway in Texas Public Higher Education. Doctor of Philosophy (Higher Education), May 2016, 272 pp., 1 table, references, 144 titles. Community college students transfer to public universities experiencing a pathway filled with complexity and inequity. Transfer students are not able to graduate at the same pace as native students at the university and complete their baccalaureate degrees 18% below the rate of native students. Policymakers have attempted to address the baccalaureate gap. This qualitative study explored the perspectives of Texas policymakers and policy influencers on the efficacy of policies intended to improve transfer outcomes. This study investigated what experience participants have with transfer policy, what their perceptions of the transfer pathway are, and how their voices can refine an understanding of policy development and ways to improve student persistence. Purposeful sampling was used to explore the perspectives of 14 Texas policymakers and those that influence policy. Findings revealed that significant gaps exist between expectations and student realities and that the completion agenda is driving policy decisions. Participants perceived that transfer students have been ignored in the completion metrics, which influence institutional priorities. -

Bidding Notes

Bidding Notes Paul F. Dubois February 19, 2015 CONTENTS 1 Preliminaries 6 1.1 How to Use This Book.....................................6 1.2 Casual Partners.........................................7 1.3 Acknowledgments.......................................7 1.4 Notation and Nomenclature...................................7 1.5 The Captain Concept......................................8 2 Hand Evaluation 9 2.1 Basic System..........................................9 2.1.1 Adjusting to the Auction................................ 10 2.1.2 Losing Trick Count................................... 10 2.2 Bergen Method......................................... 11 2.3 Examples............................................ 11 2.4 What Bid To Open....................................... 11 3 Reverses 13 3.1 Reverses by Opener....................................... 13 3.1.1 Responding To Opener’s Reverse........................... 13 3.2 Reverses By Responder..................................... 14 4 Opening Notrump 15 4.1 How To Choose A Response To 1N.............................. 15 4.1.1 Responding With No Major Suit Or Long Minor................... 16 4.1.2 Responding With A Major Suit Or Long Minor.................... 16 4.2 Stayman Convention...................................... 16 4.3 Major Transfers......................................... 17 4.3.1 When the transfer is doubled or overcalled...................... 18 4.3.2 Interference before transfers.............................. 19 4.4 When Responder Is 5-4 In The Majors............................