Here It Does Not Provide for a Level Playing Field Within the Air Transportation Industry, Particularly in Its Special Treatment of Orbitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jessie J.Pdf

Jessie J Jessica Ellen Cornish was born on 27th of March 1988 in Redbridge, London in UK. Her stage name is Jessie J. Jessie began singing with 11 years in showbusiness. She appeared in a West End production of Whistle Down the Wind by Andrew Lloyd Webber. She attended Colin’s Performing Arts School. At the age of 16 she began studying musical theater at the BRIT School, and joined a girl group called Soul Deep at the age of 17. She sang there for 2 years and then she left the group and became an independent singer. Young Jessie J When she was 17 she wrote her first song, Big white room, which has become a signature song for her. She wrote it after she was hospitalized while sharing a room with a younger boy who later sadly lost his life. Her life is very ordinary. She is the youngest of three children and she is a singer and songwriter. She sings R&B, soul, pop and hip – hop. Her father is a social worker and her mother is kindergarten teacher. Her sister Hanna is a fotographer and her second sister Rachel is a childminder. 2006–2009: Career beginnings She had signed on with now-defunct Gut Records, having fallen to bankruptcy. She now has a publishing arrangement with SONY ATV and shows great promise as a writer. Her song, Sexy Silk, was picked by Nivea for a campaign. She has also written for Chris Brown and Lisa Lois. Jessie J was responsible for making Miley Cyrus’ song’s, one of them is Party In The USA which is one of her greatests hits. -

Jessie Girl Sheet Music

Jessie Girl Sheet Music Download jessie girl sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of jessie girl sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 35965 times and last read at 2021-09-23 21:37:29. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of jessie girl you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Vocal Guitar, Voice, Alto Saxophone, Bass Guitar Tablature Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Intermediate [ Read Sheet Music ] Other Sheet Music Training Jessie Training Jessie sheet music has been read 7660 times. Training jessie arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 23:36:51. [ Read More ] Flashlight Lead Sheet Performed By Jessie J Flashlight Lead Sheet Performed By Jessie J sheet music has been read 10256 times. Flashlight lead sheet performed by jessie j arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 05:54:06. [ Read More ] Domino Lead Sheet Performed By Jessie J Domino Lead Sheet Performed By Jessie J sheet music has been read 12609 times. Domino lead sheet performed by jessie j arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 05:53:51. [ Read More ] Jessie Song Jessie Song sheet music has been read 7352 times. Jessie song arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 07:06:29. -

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Price Tag Jessie J Strum Pattern: D D D DU UD D DU

Price Tag Jessie J Strum Pattern: D d D DU UD D DU Intro: / C - - - / Em - - - / Am - - - / F - - - / C Em Seems like everybody’s got a price, Am I wonder how they sleep at night. When the sale comes first, F And the truth comes second, Just stop, for a minute and C Em Smile:) Why is everybody so serious? Am Acting so darn mysterious You got your shades on your eyes F And your heels so high That you can't even have a good C Time. Pre-chorus: Em Everybody look to their left (yeah) Am Everybody look to their right (ha) Can you feel that (yeah) F Well, pay them with love tonight Chorus: C It's not about the money, money, money Em We don't need your money, money, money Am We just wanna make the world dance, F Forget about the Price Tag. C Ain't about the Ka-Ching Ka-Ching. Em Ain’t about the Ba-Bling Ba-Bling Am Wanna make the world dance, F Forget about the Price Tag. C Em We need to take it back in time, Am When music made us all unite F And it wasn't low blows and reality shows*, Am I the only one gettin C Em tired? Why is everybody so obsessed? Am Money can't buy us happiness. F If we all slow down and enjoy right now Guarantee we'll be feelin’ C All right. Pre-chorus Chorus Breakdown (repeat C Em Am F) Yeah yeah, Well, keep the price tag And take the cash back Just give me six strings and a half stack And you can keep the cars Leave me the garage And all I..Yes all I need are keys and guitars And guess what, in 30 seconds I’m leaving to Mars Yea we leaving across these undefeatable odds Its like this man, you can’t put a price on life We do this for the love so we fight and sacrifice everynight So we ain’t gon’ stumble and fall never Waiting to see, a sign of defeat uh uh So we gon keep everyone moving their feet So bring back the beat and everybody sing It’s not about…Chorus. -

Art & Finance Report 2019

Art & Finance Report 2019 6th edition Se me Movió el Piso © Lina Sinisterra (2014) Collect on your Collection YOUR PARTNER IN ART FINANCING westendartbank.com RZ_WAB_Deloitte_print.indd 1 23.07.19 12:26 Power on your peace of mind D.KYC — Operational compliance delivered in managed services to the art and finance industry D.KYC (Deloitte Know Your Customer) is an integrated managed service that combines numerous KYC/AML/CTF* services, expertise, and workflow management. The service is supported by a multi-channel web-based platform and allows you to delegate the execution of predefined KYC/AML/CTF activities to Deloitte (Deloitte Solutions SàRL PSF, ISO27001 certified). www2.deloitte.com/lu/dkyc * KYC: Know Your Customer - AML/CTF: Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Empower your art activities Deloitte’s services within the Art & Finance ecosystem Deloitte Art & Finance assists financial institutions, art businesses, collectors and cultural stakeholders with their art-related activities. The Deloitte Art & Finance team has a passion for art and brings expertise in consulting, tax, audit and business intelligence to the global art market. www.deloitte-artandfinance.com © 2019 Deloitte Tax & Consulting dlawmember of the Deloitte Legal network The Art of Law DLaw – a law firm for the Art and Finance Industry At DLaw, a dedicated team of lawyers supports art collectors, dealers, auctioneers, museums, private banks and art investment funds at each stage of their project. www.dlaw.lu © 2019 dlaw Art & Finance Report 2019 | Table of contents Table of contents Foreword 14 Introduction 16 Methodology and limitations 17 External contributions 18 Deloitte CIS 21 Key report findings 2019 27 Priorities 31 The big picture: Art & Finance is an emerging industry 36 The role of Art & Finance within the cultural and creative sectors 40 Section 1. -

Adjectives & Adverbs

What, Why, and How? 14 GRAMMAR Adjectives and Adverbs Fragments Appositives Possessives Articles Run-Together Sentences Commas Subject & Verb Identification Contractions Subject-Verb Agreement Coordinators Subordinators Dangling Modifiers Verb Tenses Grammar chapter overview: Adjectives and Adverbs: These are words you can use to modify—to describe or add meaning to—other words. Adjectives modify nouns or pronouns. Examples: young, small, loud, short, fat, pretty. Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, and even whole clauses. Examples: really, quickly, especially, early, well. Appositives: Appositives modify nouns for the purpose of offering details or being specific. Appositives begin with a noun or an article (a, an, the), they don’t have their own subject and verb, and they are usually set off with a comma. Example: The car, an antique Stingray, cost ten thousand dollars. Articles: The English language has definite (“the”) and indefinite articles (“a” and “an”). The use depends on whether you are referring a specific member of a group (definite) or to any member of a group (indefinite). Commas: Commas have many uses in the English language. They are responsible for everything from setting apart items in a series to making your writing clearer and preventing misreading. Contractions: Apostrophes can show possession (the girl’s hamster is strange), and also can show the omission of one or more letters when words are combined into contractions (do not = don’t). Coordinators: Coordinators are words you can use to join simple sentences to equally stress both ideas you are connecting. You can easily remember the seven coordinators if you keep in mind the word FANBOYS (For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So). -

Repertoire Liste Gesamt2020

Titel Komponist / Interpret Stil Hello Adele Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele Pop Someone Like You Adele Pop Don´t You Remember Adele Pop Don´t Wanna Miss A Thing Aerosmith Pop A Tisket A Tasket Al Feldman Jazz Empire State Of Mind Alicia Keys R&B If I Ain´t Got You Alicia Keys R&B No One Alicia Keys R&B Back to Black Amy Winehouse Pop Rehab Amy Winehouse Pop Valerie Amy Winehouse Pop Auf Uns Andreas Bourani Pop Dindi Antonio Carlos Jobim Jazz Almost Is Never Enough Ariana Grande Pop Gentle Rain Astrud Gilberto Jazz Bootylicious Beyoncé R&B Crazy In Love Beyoncé R&B If I Were A Boy Beyoncé R&B Ain´t No Sunshine Bill Withers Soul Just The Two Of Us Bill Withers Soul Lovely Day Bill Withers Soul Lovely Billie Eilish Pop Make You Feel My Love Bob Dylan Folk I Shot The Sheriff Bob Marley Reggae Stir It Up Bob Marley Reggae Waiting In Vain Bob Marley Reggae Toxic Britney Spears Pop Stronger Britney Spears Pop Treasure Bruno Mars Pop Versace on the floor Bruno Mars Pop Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Pop Polka Dots and Moonbeams Burke / Van Heusen Jazz Alfie Burt Bacharach Jazz Ain´t Nobody Chaka Khan Soul 500 Miles High Chick Corea Jazz You´re Everything Chick Corea Latin Thousand Years Christina Perri Pop I´d Rather Be Clean Bandit Pop Einmal um die Welt Cro Pop 1 Bye Bye Cro Pop Traum Cro Pop Get Lucky Daft Punk Pop Lady Bird Dameron / Cornfield Jazz Fever Davenport / Cooley Swing When Love Takes Over David Guetta Pop Four Davis/ Ross Jazz Teach Me Tonight de Paul / Cuhn Jazz Angel Eyes Dennis / Brent Jazz Be Happy Dixie D´Amelio Pop Blue Bossa Dorham -

Price Tag Jessie J Featuring BOB Lead Sheet In

Price Tag Jessie J Featuring B O B Lead Sheet In Original Key Of F Sheet Music Download price tag jessie j featuring b o b lead sheet in original key of f sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of price tag jessie j featuring b o b lead sheet in original key of f sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 5215 times and last read at 2021-09-23 02:46:00. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of price tag jessie j featuring b o b lead sheet in original key of f you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Vocal Guitar, Alto Recorder, Alto Saxophone, Alto Voice, Baritone Voice, Bass Voice, Bassoon, English Horn, Flute, Harpsich Ensemble: Mixed Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Despacito Remix Featuring Justin Bieber Lead Sheet In Original Key Of Bm Despacito Remix Featuring Justin Bieber Lead Sheet In Original Key Of Bm sheet music has been read 3620 times. Despacito remix featuring justin bieber lead sheet in original key of bm arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 01:01:13. [ Read More ] Domino Lead Sheet Performed By Jessie J Domino Lead Sheet Performed By Jessie J sheet music has been read 2784 times. Domino lead sheet performed by jessie j arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. -

Geoengineering: Parts I, Ii, and Iii

GEOENGINEERING: PARTS I, II, AND III HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION AND SECOND SESSION NOVEMBER 5, 2009 FEBRUARY 4, 2010 and MARCH 18, 2010 Serial No. 111–62 Serial No. 111–75 and Serial No. 111–88 Printed for the use of the Committee on Science and Technology ( GEOENGINEERING: PARTS I, II, AND III GEOENGINEERING: PARTS I, II, AND III HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION AND SECOND SESSION NOVEMBER 5, 2009 FEBRUARY 4, 2010 and MARCH 18, 2010 Serial No. 111–62 Serial No. 111–75 and Serial No. 111–88 Printed for the use of the Committee on Science and Technology ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://science.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 53–007PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY HON. BART GORDON, Tennessee, Chair JERRY F. COSTELLO, Illinois RALPH M. HALL, Texas EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER JR., LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California Wisconsin DAVID WU, Oregon LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas BRIAN BAIRD, Washington DANA ROHRABACHER, California BRAD MILLER, North Carolina ROSCOE G. BARTLETT, Maryland DANIEL LIPINSKI, Illinois VERNON J. EHLERS, Michigan GABRIELLE GIFFORDS, Arizona FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma DONNA F. EDWARDS, Maryland JUDY BIGGERT, Illinois MARCIA L. FUDGE, Ohio W. -

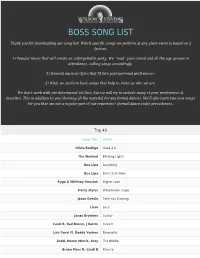

Boss Song List

BOSS SONG LIST Thank you for downloading our song list! Which specific songs we perform at any given event is based on 3 factors: 1) Popular music that will create an unforgettable party. We “read” your crowd and all the age groups in attendance, calling songs accordingly. 2) General musical styles that fit into your personal preferences. 3) What we perform best; songs that help to make us who we are. We don’t work with pre-determined set lists, but we will try to include many of your preferences & favorites. This in addition to you choosing all the material for any formal dances. We’ll also learn two new songs for you that are not a regular part of our repertoire! (formal dances take precedence). Top 40 Song Title Artist Olivia Rodrigo Good 4 U The Weeknd Blinding Lights Dua Lipa Levitating Dua Lipa Don't Start Now Kygo & Whitney Houston Higher Love Harry Styles Watermelon Sugar Jason Derulo Take You Dancing Lizzo Juice Jonas Brothers Sucker Cardi B, Bad Bunny, J Balvin I Like It Luis Fonsi ft. Daddy Yankee Despacito Zedd, Maren Morris, Grey The Middle Bruno Mars ft. Cardi B Finesse Bruno Mars That's What I Like Bruno Mars 24K Magic Camila Cabello Havana The Chainsmokers Closer Ed Sheeran Shape Of You Justin Bieber ft. Major Lazer Cold Water Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake feat. Jay Z Suit & Tie Maroon 5 Sugar Maroon 5 Moves Like Jagger Justin Bieber What Do You Mean? Justin Bieber Sorry Clean Bandit Rather Be The Weeknd Can't Feel My Face The Weeknd I Feel It Coming Calvin Harris How Deep Is Your Love? Calvin Harris Summer Calvin Harris ft. -

Print/Download This Article (PDF)

American Music Review The H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Volume XLII, Number 1 Fall 2012 Guthrie Centennial Scholarship: Ruminating on Woody at 100 By Ray Allen There is certainly no dearth of information on America’s most heralded folk singer, Woodrow Wilson Guthrie. Serious students of folk music are familiar with the wealth of published materials devoted to his life and music that have ap- peared over the past two decades. Ed Cray’s superb biography, Ramblin’s Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie (W.W. Norton, 2004) provides an essential road map. Mark Allan Jackson’s Prophet Singer; The Voice and Vision of Woody Guthrie (University of Mississippi Press, 2007) moves deeper into the songs, while Robert Santelli and Em- ily Davidson’s edited volume, Hard Travelin’: The Life and Legacy of Woody Guthrie (Wesleyan University Press, 1999), explores his myriad contributions as a song writer, journalist, and political activist. Guthrie’s recordings abound. His seminal Dust Bowl Ballads collection, originally recorded in April of 1940 for RCA Victor, has been reissued nu- merous times, most recently in 2000 by Buddha Records. Rounder Records’ Woody Guthrie: Library of Congress Recordings, featuring highlights from the hours of singing and storytelling Guthrie recorded for Alan Lomax in March of 1940, was released in 1992. Smithsonian Folkways has produced over a dozen Guthrie compilations, most notably Woody Guthrie: The Asch Recordings, Volumes 1-4, a four CD set which brings together the best of his mid-1940s work with Moe Asch. -

'It's Not About the Money, Money, Money!'

‘It’s not about the money, money, money!’ This lyric in the popular song “Price Tag” came to mind this past week as I was evaluating state KAP (Kansas Award Portfolio) applications for 4-H projects. Songwriters Jessica Cornish, Lukasz Gottwald, Claude Kelly and Bobby Ray Simmons Jr. hit the top of the charts with their collaborative efforts to send out the message to not worry about money, but to do what you can to make the world a better place. This is a message that rang loud and clear while reading through 4-H stories as members shared their struggles and successes in their project areas. All too many times, the ultimate focus is on the end result of exhibiting at the county or state fair and taking home the champion prize and in all reality, life’s lessons have been learned throughout the process which is the definitive prize. To clarify one misconception about participating as a member, the 4-H program is for EVERYONE – it is no longer ‘Tomato’ and ‘Corn’ clubs. Orville Redenbacher began growing popcorn as a 4-H project and had an obsession of creating the perfect popping corn. Jennifer Nettles, former 4-Her and 2016 spokesperson for ‘4-H Grows Here’ credits the 4-H program with her jumpstart to success as a country music singer, songwriter and actress through her performing arts project. This largest national youth organization evolves with the times and today’s youth participate in projects that focus on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math). Two main areas of focus found in reviewing the state applications were Leadership and Citizenship.