Marcel Broodthaers, 1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read a Free Sample

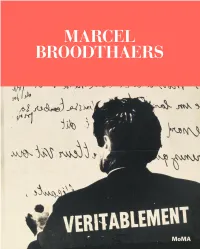

MARCEL BROODTHAERS A RETROSPECTIVE Manuel J. Borja-Villel Christophe Cherix With contributions by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh Cathleen Chaffee Jean-François Chevrier Kim Conaty Thierry de Duve Rafael García Doris Krystof Christian Rattemeyer Sam Sackeroff Teresa Velázquez Francesca Wilmott The Museum of Modern Art, New York Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid CONTENTS Directors’ Foreword / 7 Glenn D. Lowry, Manuel J. Borja-Villel, and Marion Ackermann Acknowledgments Maria Gilissen Broodthaers, followed by a conversation with Yola Minatchy / 9 Manuel J. Borja-Villel and Christophe Cherix / 12 I Am Not a Filmmaker: Notes on a Retrospective / 16 Manuel J. Borja-Villel and Christophe Cherix Rhetoric, System D; or Poetry in Bad Weather / 22 Jean-François Chevrier Figure Zero / 30 Thierry de Duve First and Last: Two Books by Marcel Broodthaers / 40 Benjamin H. D. Buchloh Poetry, Photographs, and Films Sam Sackeroff and Teresa Velázquez 52 Objects Rafael García and Francesca Wilmott 76 The Object and Its Reproduction Francesca Wilmott 116 Literary Exhibitions Sam Sackeroff 136 Le Corbeau et le Renard 140 Exposition littéraire autour de Mallarmé 156 Musée–Museum Christian Rattemeyer 166 Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles 172 The Düsseldorf Years Doris Krystof 216 Related Works 224 Emblems of Authority Cathleen Chaffee 248 Paintings Kim Conaty 270 Décors Cathleen Chaffee 290 Exhibition History / 330 Selected Bibliography / 336 Catalogue of the Exhibition and Illustrated Works / 340 Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art / 350 6 7 DIRECTORS’ FOREWORD Marcel Broodthaers is an artist’s artist. Although he is not generally widely known, he has had a profound influence on the generations of artists that have followed, and any museum committed to contemporary art crosses path with his legacy at some point. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Real Presences Marcel Broodthaers Today 11 September 2010 – 16 January 2011 Kunsthalle Düsseldorf and Kunstverein Für Die Rheinlande Und Westfalen

Real presences Marcel Broodthaers today 11 September 2010 – 16 January 2011 Kunsthalle Düsseldorf and Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen This joint exhibition by the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf and Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen presents selected works by international artists that make explicit reference to Marcel Broodthaers or that examine and further develop motifs from his oeuvre. These motifs include those that question the museum as an institution, examine imagination and outer appearance as a deconstruction of the cinematic image, and explore the relationship between language, writing and images. Ideas that were dealt with much later under the heading of institutional criticism also turn up in Broodthaers’ work, whose radical, pioneering qualities survive to this day. The exhibition conveys the Quadriennale theme “Kunstgegenwärtig” (art in the present) through the participating artists’ relationship with Broodthaers. By referring to Broodthaers’ work in a variety of ways and thus acknowledging him as a source of inspiration, they demonstrate the relevance and “real presence” of his oeuvre, even in his absence. Tacita Dean’s work Parrot depicts a parrot under palm trees in front of the Atomium in Brussels. The photograph, which the artist came across at a Brussels flea market, seems to be a rebus, a riddle to which there can be only one answer: Broodthaers. Dean is interested in exploring what is hidden and what is visible, especially with regard to unusual places and their past and present. Her films are infused with a painter’s sensibility and reflect absence and disappearance with unsettling intensity while at the same time questioning the very medium in which they are made. -

Food Art: Is It Collectible? Sharon Hecker Have You Ever Wondered

Food Art: Is It Collectible? Sharon Hecker Have you ever wondered whether to collect Food Art and how does one go about it? Does it make sense for a collector or a museum to buy an artwork that can melt, rot or stink? What is the “value” of an artwork that can organically deteriorate? What kind of art historical due diligence and conservational treatments can be conducted on such a work? Art made of ephemeral material is nothing new. For the past century, artists have been experimenting with non-traditional media in art as a way of expressing their modernity: in the early 20th century, Picasso added bits of paper, string, rope and tickets to his paintings, Duchamp exhibited his Readymades, and Gabo worked with early synthetics such as plastic. As the century moved on, there was an explosion of uses of industrial materials from plastic to steel, as well as “poor” materials like coal, felt straw, tree branches, found objects, installations and performances with things found in nature. With the advent of Fluxus, Arte povera and Pop art, anything at all became fair game for making artworks. Among these experimental media was Food Art. In some cases, this medium became appreciated for its performance value and for the symbolic meaning of the food chosen by the artist. For example, Marcel Broodthaers’ signature materials, cracked eggshells and mussels, were intended as allusions to the difference between Belgian and French cultures and cuisines. Sometimes, as with Piero Manzoni’s boiled eggs in his performance Consumazione dell’arte dinamica del pubblico divorare l’arte (1960) or Felix-González-Torres’ candy installations, the food was presented to be eaten by viewers in a form of symbolic participation in the creation of the artwork. -

Marcel Broodthaers: a Retrospective

Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective Le surréalisme révolutionnaire 1948 Periodical 10 5/8 × 8 1/2" (27 × 21.6 cm) Two copies: The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York; Private collection, Brussels Marcel Broodthaers (Belgian, 1924–1976) Louis Bourgoignie d'écriture (Louis Bourgoignie on writing) 1954 Poetry book. Pen, ten pages with plastic cover page (each): 8 1/4 x 6 1/2" (21 x 16.5 cm); overall (closed): 8 1/4 x 6 1/2 x 1/16" (21 x 16.5 x 0.2 cm) Partial gift of the Daled Collection and partial purchase through the generosity of Maja Oeri and Hans Bodenmann, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, Agnes Gund, Marlene Hess and James D. Zirin, Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis, and Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, 2011 Marcel Broodthaers (Belgian, 1924–1976) "Adieu, Police!" published in Phantômas, no. 2 April 1954 Journal, letterpress printed page (each): 7 5/8 × 5 3/8" (19.4 × 13.7 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Dr. Samuel Mandel (by exchange), 2015 Marcel Broodthaers (Belgian, 1924–1976) "Le Roi midi" published in Phantômas, no. 3 September 1954 Journal, letterpress printed page (each): 7 7/8 × 5 3/8" (20 × 13.7 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Dr. Samuel Mandel (by exchange), 2015 February 7, 2016 Marcel Broodthaers: A Retrospective Page 1 of 40 Marcel Broodthaers (Belgian, 1924–1976) La Clef de l’horloge, Poème cinématographique en l’honneur de Kurt Schwitters (The key to the clock, Cinematic poem in honor of Kurt Schwitters). -

New Media and the White Cube

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences September 2007 Within, Without: New Media and the White Cube Alexandra T. Nemerov University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Recommended Citation Nemerov, Alexandra T., "Within, Without: New Media and the White Cube" 03 September 2007. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/71. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/71 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Within, Without: New Media and the White Cube Keywords New Media, White Cube, Postmodernism, Interviews, Humanities, Visual Studies, Ingrid Schaffner, Schaffner, Ingrid This article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/71 Within, Without: New Media and the White Cube Visual Studies Senior Honors Thesis University of Pennsylvania Alexandra Nemerov Table of Contents: Introduction……………………………………………….2 Postmodernism……………………………………………6 New Media……………………………………………….16 Interviews………………………………………………...38 Barbara London………………………………...39 Roberto Bocci ………………………………….46 Douglas Crimp………………………………….52 Golan Levin…………………………………….59 Frazer Ward…………………………………….70 Works Cited……………………………………………….80 Within, Without: Nemerov 2 A new artistic platform has emerged, one reflecting and facilitating a global society’s obsession with endlessly updating, installing, applying, connecting, and configuring its representations of human experience. New Media, or digitally generated art, has become a paradigm for artists concerned with entering and mediating our relationship to technology while underscoring the increasingly surrogate experience technology affords in its supplanting of human relationships and interactions. As with any term associated with technology, New Media’s definition is constantly outdated, expanded, and updated. -

Marcel Broodthaers

[ THE SEEN ] At the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, a mock exhibition unveils Broodthaers’ enigmatic oeuvre exhibition curators Manuel J. Borja-Villel and Congolese village complete with performing to a broad American public while providing his Christophe Cherix point out, the two sculptures Marcel Africans was installed, intending to provide many admirers with new ways of looking. The together address the “failure of a country to deal Belgians a glimpse of their colony, a backward installation successfully illuminat es Broodthaers’ with its colonial past” and “the artist’s own failure ethnographic presentation described today as conceptual search through a national , social- to make a living from his poetry. ”3 —————— Broo dthaers a “Human Zo o.” This phenomenon came from political lens, underlining that even the most ——————————————— a long tradition of installations at World’s Fairs, independent thinkers are products of their Broodthaers’ works from his waking visual artist A RETROSPECTIVE // inaugurated in Paris in 1889 and practiced environment. —————————————— years (1964–68) interlace his search for artistic MUSEUM OF MODERN ART throughout the early twentieth century in ——————— The chronologically organized identity with grappling over Belgium’s national By Anastasia Karpova Tinari Germany as Völkerschau (Peoples Show) , retrospective opens with Broodthaers’ poetry, his identity. During the artist’s short life (1924– capturing the colonized in their “primitive primary occupation until age forty. Displayed 1976), Belgium was occupied by Nazi Germany, state”—the 1958 edition in Brussels was said to ephemera and books convey his interest in the freed by the Allies, briefly reinstated a monarchy, be one of the last remnants of this activity. -

Naive Engineer Panamarenko's

Naive Engineer Panamarenko's Art Panamarenko is the Belgian who makes aeroplanes. Or are they works of art as well? If you ask him this question, he will give various answers or, more probably, no answer at all. He would like to be regarded as a 'savant' . Being an artist means nothing to him. Quite the contrary, in fact. A perusal of his output – he has been working for about thirty years now – reveals fully-fledged machines, prototypes, test models and hordes of draw- ings. His creations cannot be categorised. With his own hands he pieced together an Aeroplane (Six-Rotor Helicopter) driven by means of bicycle pedals worked by the pilot himself. Then came the Portable Air Transport project: a portable, one-man flying system with internal combustion engine and propellers; various models were tested with limited results. He began a series of investigations into a closed system for accelerating matter, based on the movement of an electron around the atomic nucleus. Some sixteen scale models – the Accelerators – serve to illustrate the principle. Then there was the Piewan: a small, one-man, boomerang-shaped aeroplane, built entirely of aluminium and studded with propellers arranged in a swallow formation from its nose to the tips of itQ wines. Panamarenko, Piewan. 1975. Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent (Photo Heirman Graphics). 181 Panamarenko, Meganeudon 1973. 7,6 Private Collection (Photo Heirman Graphics). Or perhaps you would prefer a giant dragonfly? The tail of the Meganeudon ii can be folded up like a harmonica and the machine runs on large bicycle wheels. The wings, made of Japanese silk and balsa wood, are feathery and strong; they vibrate at very high speed because of a spring mechanism copied from the flight of the actual insect. -

Marcel Broodthaers. a Retrospective

Marcel Broodthaers. A Retrospective ORGANIZED BY: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and The Museum of Modern Art, New York CURATORS: Manuel Borja-Villel, Museo Reina Sofía’s director, and Christophe Cherix, chief curator of Drawings and Prints at MoMa COORDINATION: Ana Ara and Rafael García ITINERARY: MoMA, New York (February 14 – May 15, 2016) Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid (October 4, 2016 – January 9, 2017) The Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, (March 4 – June 11, 2017). RELATED ACTIVITIES: Encounter centred on Marcel Broodthaers. What happened to institutional critique? October 5, 2016 - 7:00 p.m. / Sabatini Building, Auditorium With the collaboration of: On 4 October, the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía inaugurated Marcel Broodthaers. A Retrospective, the most comprehensive anthological exhibition held to date on this artist, who was born in Belgium in 1924 and died in Germany in 1976. The show is organized jointly by the Museo Reina Sofía and The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. After the version that was shown at the MoMA in New York earlier this year, the exhibition now presents about 300 exhibits, including artworks and documentary material, demonstrating the multiple facets of Marcel Broodthaers’ work throughout his career. This artist did not come into contact with the world of the visual arts until he was about forty, having dedicated himself previously to photography, literature, poetry and art criticism. He worked in several disciplines, including sculpture, painting and film, besides holding a series of exhibitions conceived as devices for presenting his own work. His extraordinary production over the decades of the 1960s and 1970s made him one of the most important artists on the international scene, with an influence that remains today. -

Dissertation

! ! ! ! ! DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „Mimetisches Erzählen in zeitgenössischer Schweizer Performancekunst“ Eine erzähltheoretische Analyse ausgewählter Performances von Andrea Saemann Muda Mathis & Sus Zwick Yan Duyvendak Verfasserin Alexandra Könz angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr.phil.) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 317 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Dr.-Studium der Philosphie UniStG Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuer/In: O. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Greisenegger ! 2! Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort 7 Einleitung 8 I. Kontextualisierung 16 I.1 Zum Begriff „Performancekunst“ 16 Forschungsstand zur Performancekunst in der Schweiz 22 I.2 Rückblick: Entstehungslinien der Performancekunst in der Schweiz 22 I.3 Zur aktuellen Schweizer Performancekunst 31 I.3.1 Performance-Szenen 31 I.3.2 Zeitgenössische Tendenzen 36 I.4 Wissenschaftliche Reflexion 43 Forschungsstand zur Bedeutung des Erzählens in den Geisteswissenschaften und der Performancekunst 47 I.5 Vom Linguistic zum Performative und Narrative/Narrativist Turn 51 I.6 Gedächtnisforschung, Oral History: „Geschichte“ als performatives Konstrukt 59 I.7 Zeitgenössische Narratologien 67 I.7.1 Forschungslücken 68 I.7.2 Relevante Positionen 70 I.8 Bedeutung des Erzählens aus Sicht der Theater-, Performance- und Kunstwissenschaften 71 I.8.1 Traditionslinien des Erzählens in der Performancekunst – eine kritische Sichtung 73 Zum Einsatz von Sprache (75), Text und Bild (76), Politik und Gesellschaftskritik (78), Sprache als Provokation -

The Art of Marcel Broodthaers

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Another Alphabet: The Art of Marcel Broodthaers By Thomas McEvilley (November 1989) PRINT NOVEMBER 1989 Faithfully in spite of the winds that blow. I, too, am an apostle of silence. —Marcel Broodthaers UNTIL HIS 40TH YEAR, 1964, Marcel Broodthaers was a poet with an interest in the visual arts, of which from time to time he wrote criticism. His conversion from poet to artist was marked by an exhibition in which the 50 remaining copies of his recent book of poems Pense-Bête (Think like an animal1) were ensconced in a plaster base and exhibited as sculpture. After 12 years of artistic work, Broodthaers died in 1976. He had contradicted and recontradicted in the most deliberate way many of the public statements he had made about his art in the form of “open letters” and exhibition announcements. Accordingly, at his death, a certain critical void surrounded the work. No standard discourses about it had yet developed; it lay like an uncolonized territory inviting the planting of flags of possession. The currently traveling retrospective of Broodthaers tends to present his work to the American audience as perplexing or mysterious. Marge Goldwater of the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, for example, who, along with Michael Compton, organized the exhibition, uses the word “enigmatic” twice in her brief catalogue introduction; an advertisement for the Walker catalogue says that Broodthaers’ “work is ultimately enigmatic and its meaning elusive.”2 Benjamin H. D. Buchloh has similarly referred to “the highly enigmatic and esoteric character of his work.”3 So the cupboard filled with eggshells looks mutely at the viewer like a big question mark—as do the human thighbones painted in various colors, the child’s stool with the beginning of an alphabet painted on it, the plastic panels with huge commas hanging like clouds in the sky, and more. -

A Work of Art As an Experimental Exhibit. Broodthaers and the Eagle

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 6 | 2018 Experimental Art A work of art as an experimental exhibit. Broodthaers and the Eagle Susanne König Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/1050 DOI: 10.4000/angles.1050 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Susanne König, « A work of art as an experimental exhibit. Broodthaers and the Eagle », Angles [Online], 6 | 2018, Online since 01 April 2018, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/1050 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/angles.1050 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. A work of art as an experimental exhibit. Broodthaers and the Eagle 1 A work of art as an experimental exhibit. Broodthaers and the Eagle Susanne König 1 Experimentation is integral to literature and art as well as to the natural sciences. The search for new artistic means of expression, the formation of a new canon and the use of new artistic materials are all based on findings obtained through experimentation. Experimentation was a key category for the modernists in particular (Dingler 1928). The difference from previous periods lay especially in the modernists having given a new programmatic significance to experimental procedures in both the natural sciences and art. The modernists were distinguished by a stylistic pluralism as an expression of a constantly changing society, accompanied by a new understanding of art. In particular, art after 1945 gave rise to a new concept of art hardly anticipated in the traditional genres of painting and sculpture, for example.