Nishida 2010 R.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaii Been Researched for You Rect Violation of Copyright Already and Collected Into Laws

COPYRIGHT 2003/2ND EDITON 2012 H A W A I I I N C Historically Speaking Patch Program ABOUT THIS ‘HISTORICALLY SPEAKING’ MANUAL PATCHWORK DESIGNS, This manual was created Included are maps, crafts, please feel free to contact TABLE OF CONTENTS to assist you or your group games, stories, recipes, Patchwork Designs, Inc. us- in completing the ‘The Ha- coloring sheets, songs, ing any of the methods listed Requirements and 2-6 waii Patch Program.’ language sheets, and other below. Answers educational information. Manuals are books written These materials can be Festivals and Holidays 7-10 to specifically meet each reproduced and distributed 11-16 requirement in a country’s Games to the individuals complet- patch program and help ing the program. Crafts 17-23 individuals earn the associ- Recipes 24-27 ated patch. Any other use of these pro- grams and the materials Create a Book about 28-43 All of the information has contained in them is in di- Hawaii been researched for you rect violation of copyright already and collected into laws. Resources 44 one place. Order Form and Ship- 45-46 If you have any questions, ping Chart Written By: Cheryle Oandasan Copyright 2003/2012 ORDERING AND CONTACT INFORMATION SPECIAL POINTS OF INTEREST: After completing the ‘The Patchwork Designs, Inc. Using these same card types, • Celebrate Festivals Hawaii Patch Program’, 8421 Churchside Drive you may also fax your order to Gainesville, VA 20155 (703) 743-9942. • Color maps and play you may order the patch games through Patchwork De- Online Store signs, Incorporated. You • Create an African Credit Card Customers may also order beaded necklace. -

Growing Plants for Hawaiian Lei ‘A‘Ali‘I

6 Growing Plants for Hawaiian Lei ‘a‘ali‘i OTHER COMMON NAMES: ‘a‘ali‘i kū range of habitats from dunes at sea makani, ‘a‘ali‘i kū ma kua, kū- level up through leeward and dry makani, hop bush, hopseed bush forests and to the highest peaks SCIENTIFIC NAME: Dodonaea viscosa CURRENT STATUS IN THE WILD IN HAWAI‘I: common FAMILY: Sapindaceae (soapberry family) CULTIVARS: female cultivars such as ‘Purpurea’ and ‘Saratoga’ have NATURAL SETTING/LOCATION: indigenous, been selected for good fruit color pantropical species, found on all the main Hawaiian Islands except Kaho‘olawe; grows in a wide Growing your own PROPAGATION FORM: seeds; semi-hardwood cuttings or air layering for selected color forms PREPLANTING TREATMENT: step on seed capsule to release small, round, black seeds, or use heavy gloves and rub capsules vigorously between hands; put seeds in water that has been brought to a boil and removed from heat, soak for about 24 hours; if seeds start to swell, sow imme- diately; discard floating, nonviable seeds; use strong rooting hormone on cuttings TEMPERATURE: PLANTING DEPTH: sow seeds ¼" deep in tolerates dry heat; tem- after fruiting period to shape or keep medium; insert base of cutting 1–2" perature 32–90°F short; can be shaped into a small tree or maintained as a shrub, hedge, or into medium ELEVATION: 10–7700' espalier (on a trellis) GERMINATION TIME: 2–4 weeks SALT TOLERANCE: good (moderate at SPECIAL CULTURAL HINTS: male and female CUTTING ROOTING TIME: 1½–3 months higher elevations) plants are separate, although bisex- WIND RESISTANCE: -

Mar/Apr 2021

The official publication of the OUTRIGGER CANOE CLUB M A R — A P R 2 0 2 1 The perfect place to find your perfect place Victoria Place Residence 01 Living Room Striking a balance between urban energy and island serenity, Ward Village is a truly remarkable neighborhood. With a diverse collection of stunning residences to fit different tastes and lifestyles, this is the place you’ve been looking for. ‘A‘ali‘i residences starting from the $500,000s Kō‘ula residences starting from the $500,000s Victoria Place residences starting from the low $1,000,000s welcometowardvillage.com | 808 379 3387 PRICES ARE APPROXIMATE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AT ANY TIME. THIS IS NOT INTENDED TO BE AN OFFERING OR SOLICITATION OF SALE IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE THE PROJECT IS NOT REGISTERED IN ACCORDANCE WITH APPLICABLE LAW OR WHERE SUCH OFFERING OR SOLICITATION WOULD OTHERWISE BE PROHIBITED BY LAW. WARD VILLAGE, A MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT IN HONOLULU, HAWAII, IS STILL BEING CONSTRUCTED. ANY VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF WARD VILLAGE OR THE Offered by Ward Village Properties, LLC RB-21701 CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS THEREIN, INCLUDING THEIR LOCATION, UNITS, COMMON ELEMENTS AND AMENITIES, MAY NOT ACCURATELY PORTRAY THE MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT OR ITS CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS. ALL VISUAL DEPICTIONS AND DESCRIPTIONS IN THIS ADVERTISEMENT ARE FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY. THE DEVELOPER MAKES NO GUARANTEE, REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY WHATSOEVER THAT THE DEVELOPMENTS, FACILITIES OR IMPROVEMENTS OR FURNISHINGS AND APPLIANCES DEPICTED WILL ULTIMATELY APPEAR AS SHOWN OR EVEN BE INCLUDED AS A PART OF WARD VILLAGE OR ANY CONDOMINIUM PROJECT THEREIN. WARD VILLAGE PROPERTIES, LLC, RB-21701. -

Recommended Restaurants

RECOMMENDED RESTAURANTS Dining in Wailea/Makena: HUMUHUMUNUKUNUKUAPUA’A Grand Wailea Romantic and exotic, this oceanside restaurant offers the most spectacular sunset views. Named after Hawaii's state fish, our Polynesian thatch roof restaurant floats on a saltwater lagoon filled with tropical fish. Select your own lobster from the lagoon or savor delicious Island fish and meat entrees with Polynesian or Hawaiian influences. 5:30pm-9:00pm Dinner BISTRO MOLOKINI Grand Wailea In the heart of Grand Wailea Resort, Bistro Molokini offers a relaxing, open-air ambience with breathtaking views of the Pacific and distant islands. Featuring an exhibition kitchen and kiawe wood- burning oven, the Bistro offers a delightful blend of California and Island cuisine. 11:00am-5:00pm Lunch 5:00pm-9:00pm Dinner GRAND DINING ROOM MAUI Grand Wailea With panoramic views of the beautiful Reflecting Pool, the Pacific Ocean and neighboring islands of Molokini and Kaho'olawe, the Grand Dining Room offers a daily breakfast buffet and a la carte menu in a truly stunning setting. 7:00am-11:00am Breakfast 7:00am-10:00am Breakfast (Sunday) 10:30am-1:00pm Sunday Champagne Brunch TOMMY BAHAMA’S TROPICAL CAFÉ The Shops at Wailea Tommy Bahama’s Restaurant & Bar is a unique celebration of the islands offering a relaxed escape from the hustle and bustle with truly inspired cuisine with a Tropical Caribbean Twist. 11:00am-5:00pm Lunch 5:00pm-10:00pm Dinner 5:00pm-11:00pm Dinner (Friday and Saturday) LONGHI’S WAILEA The Shops at Wailea Longhi's sets the benchmark for impeccable dining offering their award winning Italian/Mediterranean cuisine: fresh island fish, prime steaks, giant lobsters plucked fresh from their own lobster tanks, fabulous pasta dishes and the most succulent desserts. -

Wao Kele O Puna Comprehensive Management Plan

Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan Prepared for: August, 2017 Prepared by: Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nā-lehua-lawa-ku‘u-lei is a team of cultural resource specialists and planners that have taken on the responsibilities in preparing this comprehensive management for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Nā pua o kēia lei nani The flowers of this lovely lei Lehua a‘o Wao Kele The lehua blossoms of Wao Kele Lawa lua i kēia lei Bound tightly in this lei Ku‘u lei makamae My most treasured lei Lei hiwahiwa o Puna Beloved lei of Puna E mālama mākou iā ‘oe Let us serve you E hō mai ka ‘ike Grant us wisdom ‘O mākou nā pua For we represent the flowers O Nālehualawaku‘ulei Of Nālehualawaku‘ulei (Poem by na Auli‘i Mitchell, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i) We come together like the flowers strung in a lei to complete the task put before us. To assist in the preservation of Hawaiian lands, the sacred lands of Wao Kele o Puna, therefore we are: The Flowers That Complete My Lei Preparation of the Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan In addition to the planning team (Nālehualawaku‘ulei), many minds and hands played important roles in the preparation of this Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan. Likewise, a number of support documents were used in the development of this plan (many are noted as Appendices). As part of the planning process, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs assembled the ‘Aha Kūkā (Advisory Council), bringing members of the diverse Puna community together to provide mana‘o (thoughts and opinions) to OHA regarding the development of this comprehensive management plan (CMP). -

PARADISE AWAITS YOU Travel to Hawaii MILL CREEK FAMILY YMCA

PARADISE AWAITS YOU Travel to Hawaii MILL CREEK FAMILY YMCA Immerse yourself in the charms of the Hawaiian lifestyle as we explore these islands from two distinct vantage points. Travel with Ben Falcone, our Member Engagement Coordinator, on this amazing Hawaiian adventure! Enjoy the best of both worlds as you explore Hawaii by land and sea. This fabulous travel experience is10 days, featuring a 7- night NCL cruise to Kauai, Maui and the Big Island. Don’t miss your very own corner of paradise when your ship docks for two days on each island. During this time a wide array of optional on and off-board excursions are open to you. Before and after your cruise you’ll enjoy the up-close experiences only guided travel can provide. Relax at a luxurious hotel in Waikiki. “Remember Pearl Harbor” as you visit the moving USS Arizona Memorial. Travel to the famed North Shore to watch the waves roll in. See reverse side for more tour highlights. AGES: 21+ WHEN: March 16, 2018 QUESTIONS: Terry Huffer P 425 357 3023 E [email protected] OPEN TO THE COMMUNITY! YMCA OF SNOHOMISH COUNTY Mill Creek Family Branch 13723 Puget Park Drive, Everett, WA 98208 P 425 337 0123 www.ymca-snoco.org/millcreek The Y is for everyone. Financial assistance is available. Travel to Hawaii MILL CREEK FAMILY YMCA Your Tour At A Glance—10 Days, 22 Meals: 8 Breakfasts, 6 lunches, 8 dinners Board the Pride of America, the best way to island-hop Hawaii. enjoy breakfast, lunch and dinner daily aboard your cruise ship,.air fare, and all ground transportation is included with roundtrip transportation from the Mill Creek YMCA to SeaTac. -

Waikīkī Wiki Wiki Wire Apr 29—May 5, 2010

Waikīkī Improvement Association Volume X1, No. 17 Waikīkī Wiki Wiki Wire Apr 29—May 5, 2010 83rd Annual Lei Day Celebration Saturday – May 1, 2010, 9 a.m.—5 p.m. Queen Kapi‘olani Regional Park Bandstand 9:00-10:00 a.m. Royal Hawaiian Band 10:15-11:15 a.m. Investiture Ceremony for the 2010 Lei Queen & Court 11:30 a.m.-12:15 p.m. Kapena 12:30 p.m. Official Opening of the Lei Contest Exhibit by the 2010 Lei Queen & Court (approx 12:30 p.m.) 12:30-1:00 p.m. Na Wahine O Ka Hula Mai Ka Pu‘uwai 1:15-2:00 p.m. Maunalua 2:15-2:45 p.m Polynesian Cultural Center 3:00-3:30 p.m. Halau Hula ‘O Hokulani 3:45-4:00 p.m. Super B. Boy Crew 4:10-4:35 p.m. Kolohe Kai 4:40-5:15 p.m. Nesian N.I.N.E. 5:15-5:30 p.m. Announcements and Closing The Hawaiian Steel Guitar Association will play from 12:15 – 3:00 p.m., in the lei exhibit/ho‘olaule‘a area (open area between the bandstand and the shell). The Lei Contest Exhibit will be open to the public from 12:30-5:30 p.m., in the open area between the bandstand and the shell. Calling all mo‘opuna (grandchildren) - come visit Tutu (grandmother) at Tutu’s Hale from 1:00-5:00 p.m., and hear stories, learn a song, a hula, how to make a lei, and learn how to weave with lauhala. -

La Lei Hulu Study Guide.Indd

1906 Centennial Season 2006 05/06 Study Guide Na Lei Hulu I Ka Wekiu Friday, March 17, 2006, at 11:00 a.m. Zellerbach Hall SchoolTime Welcome March 3, 2006 Dear Educator and Students, Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 17, 2006, at 11:00 a.m., you will attend the SchoolTime performance by the dance company Na Lei Hulu I Ka Wekiu at Zellerbach Hall on the UC Berkeley campus. This San Francisco-based dance company thrills audiences with its blend of traditional and contemporary Hawaiian dance, honoring tradition while bringing hula into the modern realm. Na Lei Hulu I Ka Wekiu features a wonderful variety of hula dances from traditional to contemporary. This study guide will prepare your students for their fi eld trip to Zellerbach Hall. Your students can actively participate at the performance by: • OBSERVING how the dancers use their bodies • LISTENING to the songs and instruments that accompany the dances • THINKING ABOUT how culture is expressed through dance • REFLECTING on their experience in the theater We look forward to seeing you at Zellerbach Hall! Sincerely, Laura Abrams Rachel Davidman Director Education Programs Administrator Education & Community Programs About Cal Performances and SchoolTime The mission of Cal Performances is to inspire, nurture and sustain a lifelong appreciation for the performing arts. Cal Performances, the performing arts presenter of the University of California, Berkeley, fulfi lls this mission by presenting, producing and commissioning outstanding artists, both renowned and emerging, to serve the University and the broader public through performances and education and community programs. In 2005/06 Cal Performances celebrates 100 years on the UC Berkeley Campus. -

Suggested Itinerary

Honolulu Suggested Itinerary Day 1 AM 9:00 Luuanu Pali Lookout The Pali Lookout is also called the “windy mountains” for strong winds that blow 360 days a year. PM 1:00 King Kamehameha V Judiciary History Center The most famous of the 4 statues honoring Kamehameha I, who unified Hawaiian islands, is located here. ʻIolani Palace PM 2:00 It is America’s only royal palace. Currently it is a museum where tourists can make Hawaiian quilt and lei (garland necklace), and take hula lessons. Hawaii State Capitol PM 3:00 Designed with volcanoes as the motif, the Hawaii State Capitol does not have a central ceiling so you can actually see the blue sky from center of the lobby on the 1st floor. PM 4:00 Ala Moana Beach Park Enjoy sunbathing and picnicking at the Ala Moana Beach Park. Ala Moana Center PM 6:00 It is one of the largest shopping malls in the world and Hawaii’s largest. There are many food courts, cafes, and restaurants in the mall. Day 2 AM 9:00 Depart hotel after breakfast Depart hotel for Day 2 after breakfast. Dole Plantation AM 10:00 This first pineapple farm in Hawaii has farm tours where you can see the process of growing various kinds of pineapples. You can also enjoy various kinds of tours and food. Laniakea Beach PM 12:00 This is where the Hawaiian green sea turtles called “honu” crawl out on the sandy beaches once or twice a day to take a nap. Giovanni’s Shrimp Truck PM 1:00 Fresh shrimp caught from a nearby shrimp farm are cooked on the spot, making it a great place to eat in Hawaii despite the far distance from downtown. -

Pearl Harbor Patch Program

REMEMBER PEARL HARBOR COMPLETE ONE REQUIREMENT TO EARN THIS PATCH. [3 inch patch/white trim] [95% embroidered] Complete requirements that are age appropriate. 1. On December 7th, 1941 Pearl Harbor was attacked. It is commemorated at the Museum in Hawaii and around the country. Take a field trip to one of the museums that will be commemorating this day around the country, OR partici- pate in an activity at school or an event presenting Pearl Harbor, OR listen to one of the student webcasts focusing on the events of that momentous day. Optional: You can also make a donation to Pearl Harbor. 2. Pearl Harbor got it’s name due to the large amount of pearls once found in the waters. It is the largest natural harbor in the State of Hawaii and the number one visitor destination on Oahu. Learn more about Pearl Harbor by reading an article, completing an informational worksheet, the official website, book, or any other literature related to the subject. Older participants, can watch a video or movie related to Pearl Harbor. Adults should review prior to them viewing it. Crossword Puzzle is located in this packet. 3. Learn more about a hero from the Pearl Harbor. You can read about one from a book, in school or on the internet. What is their name and what did you learn about them? https://pearlharboroahu.com/category/pearl-harbor-history/pearl-harbor-heroes/ 4. The USS Arizona Memorial is located in Pearl Harbor. It marks the place that Pearl Harbor was at- tacked on December 7, 1941. -

N Lei Hulu Wkiu Study Guide 0809.Indd

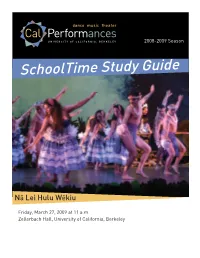

2008-2009 Season SchoolTime Study Guide Nā Lei Hulu Wēkiu Friday, March 27, 2009 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 27 at 11am, your class will attend a SchoolTime performance of Nā Lei Hulu Wēkiu. This San Francisco-based dance company thrills audiences with its blend of traditional and contemporary Hawaiian dance, honoring the ancient art form of hula while bringing it into modern culture with a wonderful variety of hula dances, live music and opportunities for audience participation. Using This Study Guide Prior to the performance, we encourage you to engageg g yyour students and enrich their fi eld trip with these prepared materials: • Copy the student resource sheet on pagege 2 & 3 and hand itit out to your students several days before the show. • Discuss the information on pages 4-6 aboutbout thethe performancep andand thetht e artistsartists with your students. • Read to your students from the About thehe Art FFormorm on page 7. • Engage your students in two or more of the activities on pages 12-15. • Refl ect with your students by asking themem guiding questions from pages 2, 4 & 7. • Immerse students into the art form by using the resource sections and glossary on pages 15-16. At the performance: Your students can actively participate during thee performance by: • LISTENING to the songs and instrumentss that accompany the dances • OBSERVING how the dancers move their bbodiesodies to tell a story • THINKING ABOUT the culture, history andd ideasideas expressed through the music • REFLECTING on the sounds, sights, and performanceperformance skills experienced at the theater We look forward to seeing you at SchoolTime! SchoolTime Nā Lei Hulu Wēkiu | III Table of Contents 1. -

December 2019 (Hawaii)

11:19 AM- Layover - Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) 1:00 PM Duration: 1 hr, 41 mins 1:00 PM- Wheels Up Los Angeles (LAX), en route to Daniel K. Inouye International Airport (HNL) 4:58 PM Flight Number: United 1431 Confirmation: LRSNZF Seat: 21C AiC: (b) (6), (b) (7)(C) Staff: Tami Heilemann Flight Time: 5 hrs, 58 mins Time Change: -2 hours 4:58 PM Wheels Down Daniel K. Inouye International Airport (HNL) // Proceed to Vehicles 5:30 PM- Depart Airport, en route to RON 6:55 PM Location: Hilton Garden Inn Waikiki Beach 2330 Kuhio Ave Honolulu, HI 96815 Manifest: Secretary’s Vehicle: THE SECRETARY AiC (b) (6), (b) (7)(C) Staff Vehicle: Nick Davis Tami Heilemann Drive Time: 20 mins 7:15 PM Dinner Reservation at Hula Grill Location: Located in Outrigger Waikiki Beach Resort 2335 Kalakaua Ave #203 Honolulu, HI 96815 Note: Dinner is pay your own. RON Honolulu, HI Location: Hilton Garden Inn Waikiki Beach 2330 Kuhio Ave Honolulu, HI 96815 Note: This concludes the Secretary’s official daily schedule. 2 Brian Schatz, U.S. Senator Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard Congressman Ed Case Clare Conners, Attorney General, State of Hawaii Kirk Caldwell, Mayor, City & County of Honolulu Mike Victorino, Mayor, County of Maui Isoda Tatsunobu, Mayor, Nagaoka City Gen. Charles Q. Brown, Jr. (COMPACAF) Aileen Utterdyke, President/CEO, Pacific Historic Parks LtGen Michael Minihan (Chief of Staff, U.S. INDO-Pacific Command) 7:45 AM Move to Seating 7:50 AM- 78th Anniversary Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day Commemoration Ceremony 9:15 AM Location: Pearl Harbor Visitor